"What's New" Archives: March 2013

March 28, 2013:

March 12, 2013:

March 11, 2013:

A Day in the Life: Walt Kelly, 1969

March 28, 2013:

Too Damn Busy

I've been consumed lately with work on Funnybooks, which has gotten in the way of putting up posts that I very much want to write, like a review of Sick Little Monkeys, Thad Komorowski's book about Ren and Stimpy and the ongoing artistic train wreck that John Kricfalusi's professional life has become. Yes, if you care about animation, and specifically about what is probably the only television animation of the last few decades that is worth a minute of your time, you should buy the book. I'll try to explain why sometime within the next few weeks.

As it happened, I read Sick Little Monkeys immediately aftering reading Sean Howe's Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, and in both cases, as I thought about the people who made the cartoons and the comic books, the phrase "deranged adolescent egomaniacs" came rushing to the surface of my mind. I won't be reviewing the Howe book, since my interest in Marvel comic books evaporated in the early seventies—that is, around the time they began to be edited, written, and drawn by people who had grown up as superhero fans and who took their heroes, and themselves, entirely too seriously. But if your interest is stronger than mine, Howe does an admirably thorough job of writing about the comic books and the people who made them.

In the meantime, if you're thirsting for substantive postings about animation and, occasionally, the comics, there's no better source than Michael Sporn's Splog. I am constantly amazed that Michael posts so much, and that so much of it is really good. Today, for example, you can read his review of The Croods, a DreamWorks Animation feature that I plan to do my best to avoid, for all that I've admired Chris Sanders's work in Lilo and Stitch and How to Train Your Dragon. It seems that not even a talent as great as Sanders can escape being chewed up in DreamWorks' cliché machine. I've enjoyed Michael's posts on Bill Nolan and Grim Natwick, too, posts enriched not just by Michael's insights as a seasoned animation professional but also by lots of well-chosen frame grabs; and then there are his posts about good people I knew or wanted to know, like Mary Eastman and Hardie Gramatky. I visit Splog every day, and you should, too.

In the meantime, if you're thirsting for substantive postings about animation and, occasionally, the comics, there's no better source than Michael Sporn's Splog. I am constantly amazed that Michael posts so much, and that so much of it is really good. Today, for example, you can read his review of The Croods, a DreamWorks Animation feature that I plan to do my best to avoid, for all that I've admired Chris Sanders's work in Lilo and Stitch and How to Train Your Dragon. It seems that not even a talent as great as Sanders can escape being chewed up in DreamWorks' cliché machine. I've enjoyed Michael's posts on Bill Nolan and Grim Natwick, too, posts enriched not just by Michael's insights as a seasoned animation professional but also by lots of well-chosen frame grabs; and then there are his posts about good people I knew or wanted to know, like Mary Eastman and Hardie Gramatky. I visit Splog every day, and you should, too.

Les Trois Petits Cochons

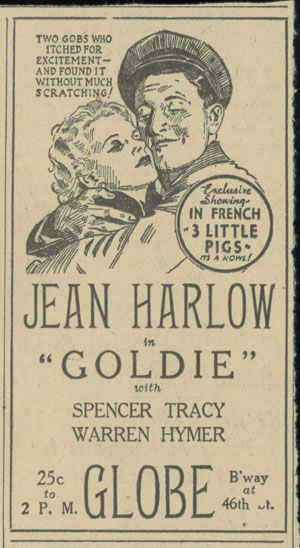

John McElwee is the proprietor of another remarkable blog, Greenbriar Picture Shows, an ongoing source of detailed and fascinating information about the Hollywood movies of decades past, animation sometimes included, and he has shared with me the advertisement at the right. John writes:

I came across, just now while indexing theatre ads from the 30's, a very unusual Broadway playdate for The Three Little Pigs in November 1933. The Disney cartoon was presented in French as an "exclusive showing." The Globe Theatre was not an ethnic or foreign language house, having opened originally in 1910 as a legit venue. It later closed, then was reborn as the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre in 1958. It seated 1,415.

If nothing else, the engagement, and this ad, demonstrates the enormous and ongoing appeal of Three Little Pigs as it ran late into 1933. Perhaps the novelty of hearing Disney's Pigs in French drew repeat patronage eager for another helping of the animated hit.

I knew that the French-dubbed version of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs played a Manhattan engagement, but I don't recall knowing that the French version of Three Little Pigs did.

If, back in 1933, you wanted to see Les Trois Petits Cochons but didn't care about the feature, you might have had to think hard about the cost in that Depression year. Twenty-five cents then was the equivalent, according to one inflation calculator, of $4.38 today. A dime or fifteen cents would have been manageable, surely, but a quarter? Maybe a bit rich.

Fess Parker in Norway

I know that Disney live-action movies are of limited interest to many of the people who visit this site, but I can't resist posting an item that Gunnar Andreassen recently sent me. I'm a Fess Parker fan, and I count my acquaintance with him as one of the best things I carried away from work on my Walt Disney biography, The Animated Man. An opportunity to revisit my memories of Fess is always welcome.

I've known for a long time about Fess' 1956 visit to Europe, when Davy Crockett mania was striking there after ebbing in the United States, but I don't recall ever seeing a contemporaneous newspaper report from one of the countries Fess visited. But here, thanks to Gunnar, is a translation of an article in the largest Norwegian newspaper, on April 27, 1956, about Fess’ visit to Oslo:

"I came as soon as possible after school," said one of the boys who stood in line at the Fornebu Airport yesterday . Along with a few hundred others with similar interest, mostly boys, but also many girls, he waited for the American children’s— and therefore also the Norwegian children’s— new "hero," comic book hero, adventure book hero and American Indian film hero Davy Crockett. The plane arrived from Copenhagen with Fess Parker himself, who plays the title role in the film Davy Crockett.

The kids who pushed against the fence and yelled "Davy," were probably slightly disappointed as Parker stepped out of the plane and it turned out that he was not in "uniform." He was one meter and ninety-six cm., but he wore an ordinary gray coat. He had neither gun nor buckskin shirt and fur cap made of "coon," as the small American raccoon is called. But on the other hand, nine-year-old Terje Christensen of Kampen School had a complete "Davy Crockett" equipment, and he was allowed to stand near the plane and be the first to greet the popular guest when he set foot on Norwegian soil. Parker pleasantly greeted both Terje and the hundred other fans in the front row along the fence. By the way, it seemed as though he modestly tried to get away from fame and hero glory of his film role. His first words were: "Davy Crockett died 120 years ago!"

The real David Crockett was known as an American hunter and forest man who fought the Indians in the early 1800s. He later became a politician and was elected to Congress. In the struggle to liberate Texas, which was then a Mexican province, he was captured by the Mexicans and shot. The hero's death after fortress Alamo fell, however, proved a bit of a problem for film producer Walt Disney one hundred years later. The television film series about "Davy" ends—completely historically accurate—with this sad event. Complete national mourning broke out in the U.S.A. Disney received 15,000 maudlin protest letters every week and thousands of boys walked in a demonstrations with posters: "Don’t let Davy Crockett die at the Alamo." The result was that Disney had to wake Davy to live again and the television series about him continued.

Film star Fess Parker, who in almost all Americans' eyes now is identical with Crockett, is 29 years old. He was born in Texas, where his parents have a farm, and he has from his film revenues bought a farm next to his father’s. Actually, he had thought himself to have an academic career, he earned a university degree and wanted to study theater history. In order to get some practical experience of theater life, he tried his hand in acting and got a role in the play Mister Roberts, which incidentally recently was shown here as a film. After he came to Hollywood, he got some minor jobs while he as a living sorted underwear in a large department store on the night shift. Among the few films he ever participated in was a "horror movie" with eerie giant ants [Them]. ... One day Disney went through some old movies to try to find an actor that he could use for the planned film series about the national hero Crockett. When he saw Parker among giant ants, he cried: "There is Davy Crockett! Who is that guy?"

Before he came here, the boys and girls in Oslo knew him only from comics, books, etc., but on the occasion of the star's visit the color film Davy Crockett was shown in a special showing at Eldorado Cinema yesterday, and Parker was presented to the youthful audience from the stage—in buckskin and coonskin cap. And not just that, he also talked and played the guitar and was one of the nicest movie stars who have visited Oslo to this date.

My interview with Fess Parker, from 2003-2004, is at this link, and my post after his death in 2010 is at this one.

An April 6, 2013, update: From Gunnar Andreassen, a few frame grabs from Norwegian television coverage of Fess Parker's 1956 arrival in Oslo:

Gunnar has also sent this link to a very brief, silent clip of Fess Parker's arrival in London that year.

From Didier Ghez: From an interview with Betty Bigle, wife of Disney Legend Armand Bigle, which I conducted on July 20, 2009.

Betty Bigle: When Davy Crockett”was released my husband [Armand Bigle, Head of Disney Europe at the time] said to Walt, “You will see. I will make the French people wear the coonskin caps.” I told him, “Do you realize what you are saying?” At the time my kids would dress in a suit and tie to go to school. “They will never…” He said, “You will see.” He went to see the famous Parisian hairdresser Alexandre and told him: “Could we make wigs with a coonskin tail?” So they created that. And he got the Comte de Paris and he went on TV with his wife and their kids, all wearing the Davy Crockett hat.And we made Fess Parker come. He told them, “You can’t name Fess Parker, “Fess Parker” in France.” [Fess meaning “Ass” in French] So he was called “Fier Parker” in France. [Fier meaning “Proud” in French.]

[Posted March 29, 2013]

March 12, 2013:

| From the Madrid production of The Perfect American. The figure at the center of the stage is supposed to be not Walt, but Andy Warhol. What is Andy Warhol doing in this opera? You'll just have to watch it. |

Watching The Perfect American

Philip Glass' opera The Perfect American, which is ostensibly about Walt Disney, can now be seen streaming on the internet, through the site called medici.tv. (Thanks to Brent Swanson for the link.) You can find video of a live February 6 performance from the world premiere engagement at Madrid's Teatro Real at this link. Medici is a subscription service, but you can for the time being see The Perfect American for free, simply by registering (and providing a minimal amount of information about yourself). The opera is in English, and there are no subtitles—not necessary for some of the singers, like those who play Walt and Roy Disney and who enunciate clearly, but subtitles would be welcome in other cases. Not that you really need them to follow what's going on. The music has its moments, although if I'm going to watch an opera by a minimalist composer, I'll go with John Adams (Nixon in China).

Like the Peter Stephan Jungk novel on which the opera is based, Rudy Wurlitzer's libretto for The Perfect American is insanely stupid, but it's hardly the first opera of which that can be said. The basic idea, as so often with efforts to diminish Walt Disney, is that just about everything he did and said was the product of a neurotic obsession, a bogus idea that permeates even an ostensibly sympathetic biography like Neal Gabler's. (He loved trains? How bizarre! He must have been sick in the head!) And so we have Walt, a man whose warm feelings for animals were evident whenever he was photographed around them—in all the photos and film I've seen, he is smiling and unmistakably happy—not just regretting the childhood incident in which he panicked and killed an owl, but haunted by it for the rest of his life. And there is of course Walt the tyrannical boss, reducing his employees to interchangeable ciphers (here wearing eyeshades and identical plaid clothing) and depriving them of credit for their work. There's the Walt who wants to be cryogenically frozen; there's Walt the bigot, telling the audio-animatronic Abe Lincoln that maybe he went overboard with that equality business. There's even Walt the philanderer, carrying on a most unlikely romance with Hazel George, the studio nurse.

It's tempting to shrug off this absurd opera, which will of course be seen by a total audience much smaller than any that ever saw a popular Disney film, much less visited Disneyland in a single week. The problem is that the opera will be seen by precisely that educated, sophisticated audience that is already disposed to look down on Walt and his works, and that will find its prejudices reinforced and validated by The Perfect American. For proof, you need look no further than the February 1 issue of Time, and its three-page feature article about Glass and The Perfect American. (Thanks to Are Myklebust for scans.) The magazine quotes Glass as speaking sympathetically about Walt—sympathy not evident in the opera itself—but with unmistakable condescension: "People were more conservative then. You have to consider the context." Time, for its part, describes Walt "as much a bully as he was a genius."

"What makes this opera interesting," Glass told Time's Lisa Abend, "is that it shows the best of American character—and some of the worst." Anyone looking for the "the best" in The Perfect American should be prepared for a long search.

From Kevin Hogan: I don’t see very much on the internet about this. Is it really getting much publicity? I wonder if ignoring this will be the best way of squashing this. I certainly would not be aware of it without your alerts.

MB replies: Actually, there's a lot on the internet (and in print, as with the Time article) about The Perfect American, just not on Disney fan sites and such. There will be, I'm sure, a lot more posted and published about the opera when it opens in London in June, and then again when it opens in the United States. Which is the point, actually. The Perfect American will shape the attitudes of people beyond the reach of the Disney fan sites or even serious books like mine, perhaps for generations to come. You might ask, is it really conceivable that a false and tendentious theatrical piece, even if it is artistically impressive, can so warp the thinking of educated audiences as to lead them to believe the worst of a public figure whom many knowledgeable scholars believe was admirable and intelligent? Perhaps you should direct that question to King Richard III.

[Posted March 13, 2013]

From Kevin Hogan: I trust your judgment then. I know that The Animated Man and your website are trying to create a fair picture of Disney, and you would likely know better if guns need to blaze or not.

Hopefully this “thing” will not do more harm to Walt Disney’s increasingly (and unfairly) tarnished image. Although, I am afraid that the so-called intellectuals who are likely to see the opera are the choir that Glass does not need to preach to. It is hard to find a person with a degree who does not believe that Walt was the sexist/ bigot/ anti-Semite that many make him out to be.

[Posted March 14, 2013]

From Don Peri: I sent a letter to Time right after the Glass article came out criticizing both the author of the piece for unsupported controversial comments about Walt and the book upon which the musical is based. As far as I can tell, Time did not publish my letter.

Keep up the good fight![Posted March 15, 2013]

From Thad Komorowski: I'm not going to watch the Perfect American opera. Besides its being based on an abhorrent book, I've attended three operas and fallen asleep during two —so it's obviously an art form I'll never appreciate. But I think this long trend of vilifying Walt is really just really a misguided attempt at personifying hatred toward the Disney Organization. I quite openly despise the current Disney, a sentiment I'm sure you share, and relish any flak the company itself catches from any corner. But a few of these, ah, spirited parties try to go below the belt by attacking the very heart of the organization: its dead public figure founder.

They can't very well attack the living Disneyites, but they can pretty much say whatever they want about the dead without fear of legal assault. These folks feel that by attacking Walt, they're attacking the corporation by association, but what they're really doing is just getting "Walt was evil" into everyone's heads. The corporation, in turn, actually quite likes this scenario. Assessing the latter-day Walt as a warped individual diverts attention away from the twisted modern behemoth. "We've improved since those days," in other words. What other reason could they have for aiding and enabling Neal Gabler? It's a sick cycle and it's never going to go away.

On a similar topic... A friend brought up over the weekend (and I'm surprised it never gets mentioned, and a quick search on your page yields no hits) that Hans Conried, a decidedly open Jew, was featured prominently in various Walt films and TV shows. So... what antisemitism?

MB replies: Actually, I'm pretty sure that the prevailing attitude toward Walt himself in the executive ranks at the Walt Disney Company is not hostility. It is instead indifference, compounded with annoyance that stems not just from those ridiculous stories about Walt, but also from the scale of the founder's accomplishments. As I wrote six years ago in The Animated Man, and is true today, the Walt Disney Company is still strongest in precisely those areas, like animation and theme parks, in which Walt himself was most intensely interested. That's the case even though Walt has been dead almost fifty years. At today's Disney Company, by contrast, the principal departure from Walt's example seems to be the large-scale buying of other people's ideas.

As for Gabler's book, I think the "aiding and enabling" was done primarily by Roy Edward Disney and secondarily by the Iwerks family, all of them concerned (as witness Leslie Iwerks's biography of Ub) with elevating their own ancestors' reputations at Walt's expense. The outcome, of course, was yet another subtle diminishment of Walt's reputation, but without a corresponding lift for his former colleagues.

From Tom Carr: I haven't contributed any comments to your page in quite a long time, but this alleged "Disney Opera" piqued my interest (in a way). To me, it's all sort of a moot point, because I can't stand Minimalism; and for that reason alone, I'd never buy a ticket. Is there anyone else besides me who thinks that it's the classical music equivalent of Rap, just as mind-numbingly repetitous and equally worthless in any aesthetic sense? Perhaps the ideal subject for a Minimalist opera would be "The Emperor's New Clothes," because the music strikes me as exactly that. The late composer Elliott Carter (who could be called a "Maximalist"), once likened Minimalism to "Fascist dictators, endlessly shouting their repetitive slogans into the ears of the audience." So even if the libretto praised Walt Disney to the skies and painted him as a saint (which would be equally false), I'd still avoid it like the plague. As far as I'm concerned, this whole genre of music is just another symptom of the "dumbing-down of America."

[Posted March 25, 2013]

From Kevin Hogan: I’m curious—when you say "aiding and enabling was done primarily by Roy Edward Disney and secondarily by the Iwerks family,” what do you mean? I have always thought that the Iwerks family has very limited influence on the Disney company, and Roy E. was more of a figurehead than anything else toward the end.

MB replies: As for Roy E. Disney's significant role, see the acknowledgments in the Gabler book. Probably I overstated the Iwerks family's role: "indirectly" rather than "secondarily" might be more accurate. In that connection, see my review of The Hand Behind the Mouse, Leslie Iwerks's biography of her grandfather, one of a number of highly unreliable sources that Gabler cites.

[Posted March 27, 2013]

March 11, 2013:

A Day in the Life: Walt Kelly, 1969

I've posted another of my essays based on a group of photos taken on the same day, or sometimes, as in this case, within a short span of time. The subject in this case is Walt Kelly, the creator of Pogo, who was photographed in Hollywood in 1969 for publicity for The Pogo Special Birthday Special, the misbegotten TV show directed by Chuck Jones.

I've posted another of my essays based on a group of photos taken on the same day, or sometimes, as in this case, within a short span of time. The subject in this case is Walt Kelly, the creator of Pogo, who was photographed in Hollywood in 1969 for publicity for The Pogo Special Birthday Special, the misbegotten TV show directed by Chuck Jones.

The self-caricature of Kelly at the right was also distributed as part of the promotion for the show.

You can read about The Pogo Special Birthday Special—and, of course, see the photos—by clicking on this link.

From Thad Komorowski: I enjoyed the Pogo essay, of course, but I think Kelly's version of what went down is probably just as self-serving as Jones's own justification for what he did (whatever it was, I've never seen it stated, in your piece or elsewhere). There's more than a little merit to Kelly's resentment, of course, because both Tashlin and Ted Geisel were also upset with Jones over his adaptations of their published works. But think about it: if Kelly's widow's statement is true, he was more involved in the production than he was willing to admit. And that's Kelly's voice as Albert the Alligator (among others)—how much could he have been unaware of if he's doing voices, layouts, and animation? I think it's simply that Kelly didn't like the direction Jones's ego was taking the project, and once he realized he had no real power (legally or artistically) he was justifiably resentful. It's a shame Jones's later ego trips were so unlike other similar Hollywood directors: woefully bland, rather than severely flawed but still interesting.

MB replies: There are a lot of questions surrounding this episode, actually, too many, I decided, for me to fill up a page with them. For one thing, what did the contract between Kelly and MGM say? Did he have any sort of contractual say over what wound up on the screen? Little or none, I'd guess, since it was MGM's money that was putting the show on the screen, and I can't imagine MGM's giving veto power to Kelly or any other cartoonist. (I don't know if Kelly's contract with MGM is at Columbus, but I'm sure it would make interesting reading.) Why did Kelly agree to the special anyway? Was it perhaps because his wife, Stephanie, was mortally ill and he was dealing with terrible medical expenses? As for Jones, I don't know of anything he ever said about the Pogo special, other than what was in publicity for the show. What could he say?

[Posted March 11, 2013]

From Harry McCracken: When I think of The Pogo Special Birthday Special, I think of one of my last visits with Maurice Noble before he died in 2001. On a knickknack shelf on his kitchen, he had the soap-giveaway Pogo figurine produced to promote the special. We got to talking about it, and he told me that he was working at MGM on some other project when the Pogo show was in production. A box of the soap figures arrived at the studio; Kelly inspected the Pogo one and flung it across the room in irritation. Maurice picked it up, took it home and kept it. More evidence that the whole experience was not a happy one for Kelly.

From Chase Pritchard: Wonderful post on that Pogo special Jones was involved in. I wish I had some comments to respond to, but I am curious if Jones ever did speak about why he voiced a handful of Kelly's characters in it. Or for that matter, why the credits have many Jones veterans working on it (with Washam as co-director too), but nothing on Kelly. True, he has his own credit, but nowhere does it say anything about laying out, or animating, anything. Was that one of your points you skipped?

MB replies: I don't recall ever seeing any Jones comments about why he chose to voice some of Kelly's characters. Or, for that matter, any Kelly comments about why he chose to voice some of the characters. I'm afraid "self-indulgence" is the likeliest answer in both cases. As for why Kelly's credits were more limited than what Selby Kelly's interview suggests—again, I don't know. But I suspect that Kelly's contributions were quite informal, not so readily categorizable as Selby's remarks might lead one to believe. And for all I know there were union complications, or similar complications of other kinds, that limited Kelly's credits.

From Milton Gray: I saw The Pogo Special Birthday Special only one time, when it was first broadcast in 1969, so my memory may be less than perfect, but I don't remember any of the animation looking much above ordinary—it all looked to me very uniformly the same, as the work of Chuck Jones's regular animators laboring under a tight budget. But what was absolutely fantastic was one of the accompanying 30-second commercials, which was animated and featured Kelly's big bear character named Bridgeport; it was there to promote a brand of soap, I think. This character was voiced with a robust personality by Kelly and—I heard at the time—was also animated by Kelly, and it was vastly better than anything in the special itself. If only the special had been half as well done as that commercial.

I also met Walt Kelly briefly at the time, one evening at the Chuck Jones studio, but we didn't have much of a conversation as he was literally staggering drunk, and about to take the elevator up to the penthouse bar to continue drinking. I don't know if that was in any way typical of his state of mind while he was working at Chuck's studio.

[Posted March 13, 2013]

From Dan Briney: Your essay about Walt Kelly prompted me to watch The Pogo Special Birthday Special for the first time today. I was pleasantly surprised to see that, at least in appearance, the characters hadn't been overtly Jones-ified the way Tom & Jerry and the Grinch had been; everyone looked on-model for the most part. The animation was a different story; in that respect it looked very much like a Chuck Jones production, though I doubt the special would have come out much better in anyone else's hands anyway. The nature of the strip made it a bad subject for animation—I saw a great deal of Kelly-style whimsy trying to break through in the Birthday Special, but none of it translates to the screen.

Pogo was one of the most dialogue-dependent comic strips there ever was, and much of its humor came from the way Kelly played with the English language, in ways that can't be expressed in animation. Gags that would work as throwaway asides in the strip (like Churchy's "pistachio oatmeal" remark) sound strange when spoken aloud, and the absurdist lyrics of Kelly's songs are awkward and unfunny when we actually hear them sung. Bun Rabbit attempts the same holiday-marathon he performed in the strip, but here it just comes out as gibberish. I can imagine that a viewer of this special who was unfamiliar with the strip wouldn't have the slightest idea what he was watching.

I'm confused by Ward Kimball's recollection of Kelly's angry reaction to the "humanized" Hepzibah, because Kelly himself was drawing Hepzibah that way in the strip by 1970. I'm not certain at what point this change in her appearance happened (my Pogo library is missing large chunks of the '60s), but a reader of '70s Pogo wouldn't find anything strange about Hepzibah's features in the Birthday Special.

It appears to me that Jones, whether consciously or not, used Porky Pine to turn the Birthday Special into a personal vehicle for himself. It's not hard to see why Jones latched onto Porky, to the extent of doing the voice himself; the character was perfectly suited to express Jones' own brand of navel-gazing self-aggrandizement. The most purely "Jones" moments in the special all belong to Porky: at a number of points he addresses the audience directly in reaction to whatever silliness is going on, or turns a Jonesian eye our way like an exasperated Bugs Bunny.

[Posted March 16, 2013]From Steve Winer: For what it's worth, I mentioned the Pogo special to Chuck some time after Kelly had died. I said that I thought it didn't come off and he agreed. I didn't press him for his reasons for saying that (it was a conversation, not an interview) but I did go on to discuss Walt Kelly with him and he spoke of Kelly with affection and admiration, and told me a number of stories that made it clear that he had kept in contact with Kelly in at least some form for the remainder of his life.

This doesn't invalidate any of the other stories you've told here, but I think it's important to remember that both Kelly and Jones had complicated personalities with many sides.

[Posted March 19, 2013]

[In a subsequent personal message, not originally intended for posting here, Steve Winer elaborated on his experiences with Chuck Jones. I've posted that message below, with Steve's permission.]

From Steve Winer: I have great respect for your work in this field and your excellent books. I know your experiences with Chuck Jones were less than optimal and, as I've said, I would never doubt the validity of those experiences. But as we're discussing these complicated artists, I did want to grab this opportunity to touch on my own experiences with him.

Briefly, I got to know Chuck during the seventies. I had written my college thesis on his films and written him to ask if he was interested in reading it. He replied immediately (enclosing an original drawing) and I sent it to him. He read it and then contacted me and asked to meet when he was in New York. We met and when he went back to LA, we corresponded from time to time.

About a year later, I and a friend went to LA for an extended period to try to break into television comedy writing. Of course, as anyone attempting this would know, I had a lot of free time. Chuck invited me to spend as much time in his offices on Vine as I liked. I could screen films in his projection room (this was pre-video days and there were many films I had never seen). I did take advantage of his kind offer and frequently, towards the end of a working day, he would invite me into his office and we would chat.

I have to emphasize that, although I eventually had some success in television, at this time I was just a kid out of college. You've written of Chuck's ego and I suppose, as I was and still am a great fan, you could say I was feeding that ego, but I feel that the friendship Chuck offered me went way beyond any benefit he could have gotten out of it.

And I also would note that, in pretty much every conversation we had, Chuck would go on at length praising those he knew and had worked with—Michael Maltese, his animators, Tex Avery, Friz Freleng—I heard him speak with loving admiration of all those and more.

Eventually, I found work in New York, and I saw him less and less. But when I did see him, at gallery shows or elsewhere, he was always gracious—even in later years when I think he'd forgotten who I was.

So I tell you this not to wag a finger at you and say you're wrong about Chuck, but just to try to illuminate the side of him that I saw. I've always felt that one of the nicest things that can happen to you in life is to meet one of your heroes and have him or her live up to your expectations. For me, Chuck Jones did.

MB replies: I don't doubt that he did, and I'm glad of that. I always wanted to be on good terms with Chuck myself, and I was terribly disappointed when that proved to be impossible.

I've realized, too, that it's entirely possible that Chuck and Walt Kelly remained on speaking terms after the disaster of the The Pogo Special Birthday Special. I've been put in mind of people I once worked with, colleagues I counted as friends but who damaged me seriously, in one case to the tune of thousands of dollars in work I was never paid for. I'm sure I'd want to punch those guys in the nose if I ever was to see them again, and I might have done that when I was younger; but not now, when I'm older than Chuck and Walt were when they clashed over that TV show. I'd have trouble being more than polite to my former friends, but I could manage at least that much.

[Posted March 25, 2013]