INTERVIEWS

Fess Parker

An Interview by Michael Barrier

On

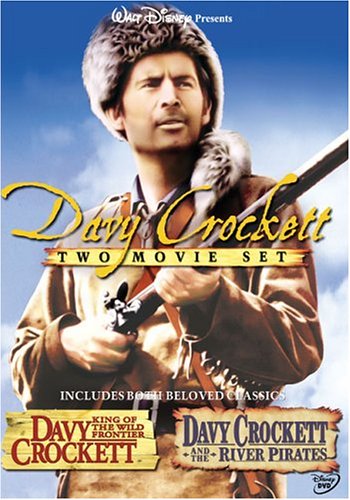

December 15, 1954, during its first season, the Disneyland

TV show aired an episode called "Davy Crockett, Indian Fighter."

It was the first of three episodes about the legendary frontiersman.

Fess Parker, who was then 30 years old, had been chosen by Walt

Disney himself to play Crockett. Disney had spotted Parker in a

2 1/2-minute bit part in a science-fiction thriller called Them!,

about huge mutated ants that were threatening the American Southwest.

On

December 15, 1954, during its first season, the Disneyland

TV show aired an episode called "Davy Crockett, Indian Fighter."

It was the first of three episodes about the legendary frontiersman.

Fess Parker, who was then 30 years old, had been chosen by Walt

Disney himself to play Crockett. Disney had spotted Parker in a

2 1/2-minute bit part in a science-fiction thriller called Them!,

about huge mutated ants that were threatening the American Southwest.

Public enthusiasm for the Crockett shows was remarkably strong. Huge crowds greeted Parker on a 22-city publicity tour in 1955, and sales of coonskin caps and hundreds of other Crockett-labeled items rose into the many millions of dollars. Writing about the Crockett craze more than thirty years later, the newspaper columnist Bob Greene was undoubtedly correct when he pointed to Parker himself as the critical element in the TV shows' success:

"In his portrayal of Crockett, Parker brought to the small screen a presence that was palpable; people looked at him, and they listened to him, and they tingled. The face and the voice combined to represent everything that was ideally male in the United States."

Although he had leapt to celebrity in a TV show, Parker's impact was that of a bona fide movie star. He was tall (six-foot-five) and handsome, but so were many other young leading men in the fifties. Parker brought to the screen two priceless assets in addition to his good looks. For one thing, he was relaxed in front of the camera as few actors are, especially in TV, where the demands for speed and efficiency have always encouraged actors to be tight and guarded. For another, he could deliver dialogue with complete conviction (a perfect example: his speech to Congress about the Indian bill in the second Crockett episode). He seemed emotionally open, as good actors must, but the emotions were those of a strong and even stoic man—one with a sly sense of humor, suited to "grinnin' down a bear." Above all, Parker conveyed sincerity, the quality Walt Disney so valued in his animators.

It's a lingering mystery as to why Disney didn't recognize Parker's worth but instead cast him in a series of misconceived or secondary roles—in support of Mouseketeers in one weak film, as an unsympathetic hero overshadowed by antique trains in another, and so on. There may be a clue in the casting of Jeff York as Mike Fink in two followup Crockett episodes in Disneyland's second season.

TV was still young then, but York fit a rapidly hardening mold, that of the aggressive, one-note comedian who relies on sheer brass to snag the attention of viewers who are watching the set with only half an eye. Through this casting of a much louder, cruder actor opposite Parker, Disney and his director, Norman Foster—a veteran of TV and low-budget movies—invited their viewers to regard Parker not as strong and quiet, but as passive. Perhaps that's what they thought of him themselves, even though his performances in the first season's shows should have told them otherwise.

Parker

never worked with a director of real talent, and he never had the

movie career that might have been his—but he has enjoyed great

success otherwise. He starred for six years (1964-70) in the Daniel

Boone TV show before leaving show business to pursue a career

as a real estate developer and hotel owner in Santa Barbara. For

the last fifteen years or so, he has also been the proprietor of

a winery that has made "Fess Parker" a highly regarded

label among oenophiles (to learn more, visit www.fessparker.com).

He is now 80 years old, but still robust and imposing, as you can

see from the accompanying photo of him, taken last year with visitors

(my wife, Phyllis, and her parents, Ida and Vernon Mathews) to his

hotel in Los Olivos, California.

Parker

never worked with a director of real talent, and he never had the

movie career that might have been his—but he has enjoyed great

success otherwise. He starred for six years (1964-70) in the Daniel

Boone TV show before leaving show business to pursue a career

as a real estate developer and hotel owner in Santa Barbara. For

the last fifteen years or so, he has also been the proprietor of

a winery that has made "Fess Parker" a highly regarded

label among oenophiles (to learn more, visit www.fessparker.com).

He is now 80 years old, but still robust and imposing, as you can

see from the accompanying photo of him, taken last year with visitors

(my wife, Phyllis, and her parents, Ida and Vernon Mathews) to his

hotel in Los Olivos, California.

The loss is not his, but ours. To cite a role that Walt Disney barred Parker from pursuing, consider the Don Murray character in Bus Stop. Murray's fine performance is actually a little scary—it's as if his character were bipolar, on an extended manic high. It's easy to imagine that Parker would have been better in the part—warmer, and far more naïve than crazy. And if Parker had not been foreclosed from trying to claim a place in the John Ford stock company, well…how much better some of the last Ford movies would be if Ford had been able to rely not just on older stars like John Wayne and James Stewart, but on a younger actor of the same stripe.

I first met Fess Parker in 1988, when I interviewed him for a business magazine. Our most recent interviews—part of the research for my Walt Disney biography—began on September 26, 2003, on the patio of Fess Parker's Wine Country Inn at Los Olivos,and continued by telephone on January 6 and February 3, 2004. Parker reviewed and approved this composite transcript.

Barrier: You were, as I recall, the first adult actor that Walt Disney signed to a long-term contract, so you have a particular significance in his work in live action. I want to get some sense from you of what it was like to work for Walt Disney in his role as a live-action filmmaker. One thing that really intrigued me was what you mentioned in a Los Angeles Times interview in 2002, that you left Disney because he turned down the opportunity for you to be lent out to John Ford for The Searchers [1956], with John Wayne. I was kind of shocked by that, because I thought it would have been a perfect matchup. Why did he turn down that loan?

Parker: Actually, it was what happened after that [that led to Parker's leaving Disney]. I was signed for 350 dollars a week, and by the time I was in my second year I may have been [up to] 500 dollars, I don't know. But I was still modestly paid. They had sent me all over the world and exploited me in every way possible, and I'd done everything I could for the opportunity. I wasn't consulted about The Searchers. I was en route with Jeffrey Hunter, who played the role [of Martin Pawley in The Searchers], and Walt Disney, on the way to Clayton, Georgia, for our locations for The Great Locomotive Chase [1956]. The conversation turned to Jeff's greatest experience of his life, which he described as [working in] The Searchers. Walt Disney turned to me—we were sitting in the back seat—and he said, "They wanted you for that." I was a newcomer, but I realized even then that you don't get too many shots, and I'd already been heavily exposed in one dimension. Then the movie that I was cast in, The Great Locomotive Chase—there was more tender loving care of the locomotives than of their live asset.

To put it simply, Walt Disney was unconcerned; he had so many things on his plate. I have no complaints. He always gave me opportunities to talk to him. But that one went by the board, and then the next one that came up was Bus Stop [1956]. I have a book that I went out and bought, the play Bus Stop. I took it to his office and I said, "I'd like to work in this picture." In the book I have his inter-office memo, with brown, crumbling edges—Walt Disney Productions, Inter-Office Communications, February 23, 1956. To Fess Parker from Walt Disney. "I am returning your copy of Bus Stop. Personally, I do not think that this is a good part for you, and what with present commitments that will carry you into September, I do not believe you ought to consider any outside things until after that time." And Don Murray, a friend of mine who lives out here in Santa Barbara—the idea that it was not a good opportunity is really kind of weird, because Don was able to do it so well [playing opposite Marilyn Monroe] that he got an Academy Award nomination. I don't know if I would have been able to have an equal amount of success, but I sure would have liked to try it.

Barrier: Were you under contract to Walt personally in the beginning? I know there were such arrangements back in those days.

Parker: Yes, the first two years of the contract I was under personal contract to him. Then I changed agents, and my agent negotiated a new contract for me, and Walt didn't want to pay it. So he put me with the studio, a new seven-year contract. Two years into that contract, I'm being cast as sort of an auxiliary character, second billed. In Old Yeller [1957], I'm at the beginning and the end. The next thing, they introduced [James MacArthur, in The Light in the Forest, 1958], so I'm still in doldrums there. Basically, I just don't think they understood that if they wanted to extract the maximum value out of me, they had to do a little thinking about it, and they weren't thinking.

Then they cast me in a picture called Tonka [1958]. I've never [even] seen it advertised. Sal Mineo was in it. I said, "Who's Sal Mineo?" "Well, he's a young actor." "OK, let me see the script." I still remember this, I was so shocked. "My name is Captain James Keogh, and this is the story of my horse Tonka." Over the titles. On the back end, page 95, five pages, I'm killed. I went to Walt and I said, "Are you going to star me in this picture?" "Oh, yes." I said, "I think that's dishonest. I haven't got anything to work with. So I disagree."

If I'd been the only thing on his mind, or if he'd paid more attention to the circumstance—but by this time, he had people doing work that he didn't want to do. So we disagreed. I said, "I'm not going to do this picture," so they put me on suspension. There was more talk between my agent and the studio, and I believed, when I went back, that I was not going to be required to do that picture. But I found that nothing had changed. So I said, "I'm sorry, I'm not going to do the picture." Any other studio, if it mattered, they would just put you on suspension until they were ready to use you again. But in this case, I never said to the studio, "I have no interest in the five years left on my contract." It was just sort of understood, and I left, and that was the end of it.

Barrier: Do you think they had run out of ideas for how they wanted to use you, and they were content to let you go? Of course, you wanted to leave—

Parker: No, I wasn't intent on leaving, at all. I had five years to go on a contract. I'm sure, from their side, they thought they were paying me a lot of money, but considering the work I'd done for them in the beginning—not just the film opportunities they gave me, because that was my obligation, but I went all over the world for that company and worked like a dog because I thought I had a vested interest in the merchandise and it was worth working for.

Barrier: So when you turned down Tonka and went on suspension and then came back, you expected that they would offer you another role, and you wanted them to.

Parker: Yes, and I can't understand it, even to this day. I talked to someone who'd seen Tonka—I've never seen it—and I [would have] had a brief message over the title and four or five pages [of the script].

Barrier: It's not a big part [Keogh is played in the film by Philip Carey]. You would have been in support of Sal Mineo. But this is what I want to get clear: it sounds as if it was more Disney's preference than yours that you leave the studio.

Parker: I had an agent who was representing me, and I don't really know what the conversation was. It kind of got down to not a suspension but "do it or else." I felt that I was right and that I had to do what I thought was right. I didn't want to go back to where I'd been.

Barrier: Walt treasured his great animators, who were in effect the actors in his animated films. It's baffling to me that he wouldn't have had some of the same feeling about the most important actors in his live-action films, particularly people who had shown they could deliver for him the way you had. I don't get it.

Parker: I don't, either. I didn't understand it. I'd only been in films for three years, so I wasn't a past master of understanding where I was, but I did understand that without the part, you've got no place to go.

After Disney, I went directly to Paramount, and I was there for four years, from '58 to '62. Then in '63, I did thirty episodes of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. The Daniel Boone show took me to '70. I turned down a television series at Universal [McCloud] that Dennis Weaver did a great job with; I would never have pulled it off like he did. I still had ideas that maybe somewhere I'd get another shot [at feature films]. Plus my family was growing up—[doing another TV series] just wasn't attractive to me.

I went to Warner Bros. the last three years that I received a paycheck from the industry. I did a pilot film; that was the only thing I did in three years. It wasn't because I was turning things down, it was just that nothing happened. I don't even know why they had me there. I had a big dressing room, a secretary, a limo any time I wanted it. I lived in Santa Barbara, so when I had business in L.A. it was nice to have the limo meet me at the airport. But it didn't make any sense.

Barrier: This Searchers thing is so intriguing—I think of you playing against John Wayne, and I think of the two of you being generally the same sort of actor. You use aspects of your own personalities to make the characters you're playing more real.

Parker: Absolutely. I'm also the first to say that accolades for the finest actors in films are all the same. Some guys change their clothes, but it's still Marlon Brando. Paul Newman is Paul Newman. The force of these individual personalities is what the business is about. How many great actors are there, in film? You may laugh when I say this, but I think Gary Cooper was one of the greatest actors ever in films. Look at the range of things that he did.

Barrier: I was going through the directors' credits on the films you appeared in at Disney, like Norman Foster on the Davy Crockett series and the various people who directed the feature films—

Parker: I want to tell you, there was not one of them on an A list.

Norman

Foster, frankly, tried to get rid of me [during the filming of the

first Davy Crockett show]. We didn't have any dailies to look at,

and I wasn't privy to that, anyway. They simply couldn't get them

back from Hollywood to where we were. Finally, they did. Foster

invited the whole company to look at them, and on the way out of

the theater, he said, "You're coming along." I said, "Well,

thank you, Norman." Then it was a little better. But he had

been placed in an awkward position. He went off to Mexico to cast

for Zorro and to find locations, only to come back and find, oh,

no, we're not doing Zorro, we're doing Davy Crockett, and here's

your boy. He felt a little out of the loop.

Norman

Foster, frankly, tried to get rid of me [during the filming of the

first Davy Crockett show]. We didn't have any dailies to look at,

and I wasn't privy to that, anyway. They simply couldn't get them

back from Hollywood to where we were. Finally, they did. Foster

invited the whole company to look at them, and on the way out of

the theater, he said, "You're coming along." I said, "Well,

thank you, Norman." Then it was a little better. But he had

been placed in an awkward position. He went off to Mexico to cast

for Zorro and to find locations, only to come back and find, oh,

no, we're not doing Zorro, we're doing Davy Crockett, and here's

your boy. He felt a little out of the loop.

Barrier: Why do you think Walt never hired strong directors?

Parker: He wanted the last word. He didn't want anybody to challenge him. When we did Great Locomotive Chase, he put a producer in place who had never produced, Larry Watkin [a screenwriter for such Disney features as Treasure Island and The Story of Robin Hood]. The director was a man who had been an Academy Award[-winning] film editor, [Francis D.] Lyon was his name. He had put together The Cult of the Cobra [1955] at Universal and pasted together the newsreels of Bob Mathias to make The Bob Mathias Story [1954], and those were his credits coming into making this picture at a distant location, with some extremely difficult logistics, and with a screenplay—when I had a chance, I said to Walt, "This screenplay just doesn't feel quite right." Historically, the character [the Union spy James J. Andrews, played by Parker] was significant, but from a storytelling point, everybody had to root for Jeff Hunter [who played a Confederate railroad conductor pursuing his stolen train] to catch us, because there wasn't any story otherwise. So, every move turned out to be somewhat less than it might have. The industry was waiting to see if I could produce another reasonably successful picture, and I didn't do much.

Barrier: Of course, there are cases where producers like Walt were exercising the kind of control that really made the films their own, but at the time you were working in the feature films, he was wrapped up in Disneyland and the TV show. He couldn't have been giving detailed attention to the films.

Parker: No, he was just satisfied with what he was seeing.

Barrier: How much do you remember of Walt being present? You mentioned his going down to Georgia for The Great Locomotive Chase.

Parker: He wasn't there very long. He wasn't a guy to hang around the set. He'd come and sit down if we were in the studio, for a little while.

Barrier: Of course, the last episode of Davy Crockett was shot at the studio, on the sound stage, instead of on location.

Parker: I don't remember him on the set at all for that. I'm sure he was, but I just don't remember it.

Barrier: Even though he was keeping the final word and he was working through these directors who weren't on the A list, still, he wasn't really shaping the films. That seems so sad. I keep thinking, if he'd been willing to hire a John Ford…

Parker: More than that. Several studios wanted to buy into my contract, so he could have farmed me out, where possibly I would have gotten some different things to do. I have no idea how they would have come out; when you're under contract, you're under contract. At least there would have been some variety.

Barrier: Do you think he was concerned, as with Bus Stop, that you might appear in a film—

Parker: He seemed to care, but I don't think he really understood it. Just the human factor, [the way] an actor [feels toward] someone holding your contract. That was shared, I think, not only by Walt but by Bill Anderson. He'd been a businessman before he came to be an administrator [at the Disney studio]. Card Walker, who rose to heights there—they weren't picture people. It all seemed to be meat and potatoes.

Barrier: You were just an employee.

Parker: Yes.

Barrier: I saw [Harrison] "Buzz" Price the other day, and he said he was always aware that the people who worked for Walt seemed to be scared to death of him. He never understood why, but there was one time when he felt that Walt treated him like an employee, and basically reamed him out in front of half a dozen important people. Was there ever a situation when you felt Walt treated you that way?

Parker: No.

Barrier: He never put you down in front of other people.

Parker: No. His secretary [Lucille Martin] is still at the studio. I used to stop by her desk and say, "I'd like to say hello to Mr. Disney, is this an opportune time?" I'd go in, and Walt might be talking to some people, [but he would say], "Have a seat, and when I get through here we'll talk." I don't remember his ever not being able to see me. Same way with Roy Disney and the chief legal counsel, Gunther Lessing. Those guys were smoking cigars, and Gunther was rolling his. We'd just sit and shoot the bull. I enjoyed being at the studio. It was very open, very pleasant, other than what I've told you here.

Barrier: It seems so strange that they would be so open, and yet so insensitive.

Parker: I don't know why I would engender that. [But considering the demands on Walt's time,] any attention was remarkable under the circumstances, even if it was flawed.

Barrier: I keep reading about the methods Disney used to control films, the detailed storyboarding, which evidently the director wasn't really in charge of. It was done at an earlier stage, so the director would be confronted with these detailed storyboards that dictated the staging and cutting of the film.

Parker: I knew they were doing that. I don't know that they did it on each and every [film that Parker appeared in]. When we did a picture called Westward Ho The Wagons! [1956], we had a veteran director who wore an eyeshade and carried the script around in his hip pocket.

Barrier: That was Beaudine?

Parker: Yes, Bill Beaudine, wonderful old guy. He was terrific. But he was used to shooting Leo Gorcey and those guys over at Monogram. This was just a thing over at Disney. I don't know if he did any more pictures after that. And where they got him, who thought this was a great idea to follow up the Crockett things—it sure wasn't Bill Walsh, because Bill was a man of good taste. He knew the business.

Barrier: But he didn't have as much say over things?

Parker: Davy Crockett and Mickey Mouse Club were his first great successes, so he was feeling his way there. But you saw his choices later on, the tremendous successful things that he wrote and produced.

Barrier: Robert Stevenson, I guess, was one director who stood out more than the others.

Parker: Bob was very nice. In my little scene in Old Yeller, I said, "You know, Bob, where I come from, a lot of times when men of the area want to talk, they kind of hunker down. I kind of see doing that in this scene." He said OK, so he put the camera there, and Tommy Kirk hunkered down and we had a little talk. And that was it.

Barrier: You must not have worked many days on that picture.

Parker: No, I didn't. Very, very few.

Barrier: Were there long stretches when you simply didn't have anything to do when you were under contract with Disney?

Parker: Oh, yes.

Barrier: That must have been frustrating.

Parker: Well, you know what? I'm a happy spirit. I had a sailboat and I went down and got on it. I didn't miss a day.

Barrier: You took advantage of the situation.

Parker: I did.

Barrier: I've heard that Buddy Ebsen was being seriously considered for the role of Davy Crockett before they discovered you. Did Buddy himself ever say anything about that to you? Had the Disney people ever talked to him about playing Davy Crockett?

Parker: Buddy was in costume when I met him. Walt Disney introduced me to him in the hallway of the studio administration building. I actually saw a list of practically every male actor in Hollywood that they had considered, looked at, some of them, rejected them out of hand, I don't know. But it was a single-spaced page, two columns of names that they had sort of run through the hoops. My inclination is that yes, he was seriously considered for it.

Barrier: But he never thought he had it and then it was taken away from him.

Parker: No, he would have said something, because we became lifelong friends. He would have said something like, "You know, Parker, you did something to me."

Barrier: You've mentioned your admiration for Gary Cooper, which I share, and you've been compared to him. You were onscreen with him in Springfield Rifle for a minute or so. What do you remember about that experience, about working with Gary Cooper? Did you carry something away from that that you were able to use later?

Parker: I had a chance to do that scene with him, and then I hope I didn't make a pest of myself, but I hung around wherever he was relaxing or in conversation—I wasn't trying to eavesdrop or anything. He was probably my favorite actor, among all the wonderful Fondas and Stewarts and so on. I think the thing that separated Cooper from most of the other actors, with the exception of Fonda, was a sort of physical grace that he possessed. He broke his hip many years earlier in a horse accident, and so it was hard for him to ride. He required a horse that was pretty narrow. I don't know if he was in pain, but whatever it was, he took care of it and handled that horse work beautifully. I still have pictures of him in my mind. He had a graceful way of spinning on his boot heels, and the man had probably the most expressive hands of any actor. You might think it's kind of peculiar to isolate items like those, but the other part of Cooper, the intellectual, the actor, however you want to describe him in his profession—it was all there, he could do comedy, drama, action. When he was Sergeant York that was one thing, High Noon was another, and he just pulled it off. He's probably the most underrated actor in my lifetime. I think the others were probably recognized—certainly Jimmy Stewart was, and Fonda, for his versatility.

Fonda had the same kind of grace; it was a more shambling kind of grace, if I can put it that way. I had the pleasure of spending a number of weeks onstage with him. It was my first job, and I stood in the wings of Mister Roberts and watched him night after night do a scene that was tough to pull off on stage. It was a recognition of what the crew had done in his behalf, and his technique, and his reaching the emotional moment—I know that it could not always be the same, but it appeared to be the same, and had the same effect. That was a great experience.

Barrier: I hadn't realized that you had done stage work.

Parker: I was in Mister Roberts the summer of 1951, from June until September. We played the Geary or the Curran, I can never remember which theater, in San Francisco, and the Biltmore Theater in downtown L.A.; it's now a parking lot.

Barrier: I've always thought of screen acting as being in many ways more difficult than stage acting, because you're shooting things out of sequence. You may be shooting on location and you step through a door, and a month later you're through the door and inside, on a sound stage. I would think it would be very difficult for an actor to perform in the sort of emotional arc I think you're describing in Fonda's performance, where you rise to a climax and your own feelings are built into the way this character is developing. As someone who was mostly a screen actor but had some stage experience, how did you compensate for the characteristics that screen acting necessarily has?

Parker: It's sort of like this: if you don't know anything about what you're doing, and they tell you to pick up the anvil—if you really want to be there, you'll pick that anvil up, one way or another. I didn't realize until later on how difficult it was. An example is my first experience onscreen to speak a line. This was my line: "You didn't say nothin' about there bein' no way to get to it from here." That sounds simple, and I probably can't repeat it again, but I waited for weeks to say that line. In fact, the director turned to the first assistant and said, "Does he speak?"

From that point on, I got jobs, and had more lines in No Room for the Groom, and finally the very popular director Douglas Sirk was doing a picture for Universal. I had a scene to do, some very brief but key lines. It was in a saloon with a whole bunch of extras and it involved a bit of tricky camera work, saying a line and holding a newspaper in the precise location it needed to be. Unfortunately, I probably held up the company for fifteen or twenty minutes, which did not make me a more popular candidate for future Universal Studios films. But that's the way it goes. When you see an actor come in and deliver a short line, these guys are working sometime without knowledge of the script. They're just kind of briefed, and they come in and deliver. It's amazing.

Barrier: We were talking about John Wayne and about actors' using aspects of their own personalities to make a character seem more real, and I would guess that's particularly important in screen acting. If you're doing a scene, and to a large extent you can play yourself—assuming you know who you are—that would give you a big head start.

Parker: I can tell you, a lot of times, actors that I've known and I've worked with, they get into a character and they basically try to stay in it till the job is over. It is a sort of mental discipline and a concept that goes back to the days when you were playing in the back yard. One day you wanted to be Clyde Beatty, and the next day it was Buck Jones. You played them both equally well.

I watched The Searchers recently, and I thought John Wayne was really outstanding in a lot of scenes. But The Shootist [1976], his last picture, was life imitating art, because he played a dying man, and he was in fact dying himself. Ron Howard, Hugh O'Brian, Lauren Bacall—all the people in that movie were just splendid.

Barrier: Speaking of The Searchers, I was thinking about how you would have fit into that Martin Pawley role that Jeffrey Hunter played.

Parker: You know, my impression was, not nearly as well as Jeff did.

Barrier: My feeling was that they would have had to rewrite that role, because you're a stronger screen presence than he was. You said that Jeff Hunter told you that working on that film was the greatest experience of his life, working with John Ford, and I'm wondering if you remember anything of what he said about what made it so special.

Parker: His first words, of what made it so special, were, "working with John Ford." For most young actors in those days, to have John Ford's interest was a fantastic thing. John Ford was such a dominant man in his arena, and at a time when the films were most popular that he was making, his company of actors were really family. If there was ever anything specific or even general that he could do for those people, he did it. So Jeff was admitted to the great circle. I don't think that he ever had another chance to work with Ford, but he had done it in a very important picture. [Hunter actually had important roles in two more Ford films, The Last Hurrah (1958) and Sergeant Rutledge (1960).]

Barrier: Of course, Ford was an icon among directors then, but what was it, for an actor, that made working with Ford so special? What did he bring to an actor, or ask of an actor, that was beyond what an actor would get from an ordinary director?

Parker: I can't remember anything that Jeff said specifically, but my hunch is that it was sort of like going to school and somebody says, "You better not get in his or her class." If you're in there, you're going to have to work extremely hard, and there's no slack. Either you cut it or you don't. Ford was so strong a person and so much of an enigma—first of all, he was hiding behind those glasses, and [one lens was opaque]. His handkerchief habit, of chewing on the handkerchief. And he wasn't social, by any means. I think the fact that you were going to work for him meant that you were at your highest level of attention. Whatever he told you to do, you'd better do it right, or you would suffer humiliation until you got it right. He was unmerciful with John Wayne, Ward Bond, you name it. It was a badge of honor to have worked with the old man. He was several people in his lifetime, really. Can you imagine him as a linebacker? His nickname in high school was "Bull." At the stage that I began to observe him, he wasn't a physical man, but he had been.

Barrier: So you actually had some personal contact with Ford?

Parker: Oh, yes. Before The Searchers was made, I went one evening to the apartment of Olive Carey, the widow of Harry Carey and Dobe Carey's [Harry Carey, Jr.] mother. This was an evening that was primarily Ford family people. It was an open house and a buffet, and there were musicians playing in the kitchen and guitars and western music and so forth. I listened to the music for a while, and my girlfriend, Marcella, was in the front, with Olive in the living room, with the ladies, so finally I decided to help myself to some of the beans and chili and whatever was on the table. As I turned away from the table, Ford was standing right beside me. He took my plate, took my fork, stuffed it into the food, popped it into his mouth a couple of times, stuck the fork back in, and turned around and walked off. I don't know how far down my chin can go, but it must have been at its optimum position. Then I went into the kitchen, and I was just listening to the music, leaning up against the cabinet, and he came in and stood beside me. That made me nervous. Then he took his elbow and jabbed it into my ribs. I turned and looked at him—I don't know what expression was on my face, but I couldn't believe it. I decided to just ignore it, and he did it again. I just kind of walked away from him and went back in the other room. What in the world can you imagine that he was after? It's still one of my funniest experiences in the film business.

Barrier: When did this happen?

Parker: I had just finished Westward Ho the Wagons!, which was the first picture Disney plopped me into. That was a picture they couldn't decide if it was for television or a movie theater. It had Mickey Mouse Club members in it.

Barrier: And this was before Ford offered you the role in The Searchers.

Parker: Yes. I didn't know much about him. I certainly had seen his movies. Liz Whitney, the wife of the producer, had come out on the set, and I had met her. Apparently, the Whitneys requested me, or approved me, or something, but I didn't realize the significance of that visit until a long time later.

Barrier: I wonder why Ford would not have pursued you for roles later.

Parker: My feeling is that if he thought that you didn't want to work with him, had any inkling of that, he wasn't the kind of guy to give you much. I went to him when they were going to make Horse Soldiers [1959], I called on him. He was officing at Batjac [John Wayne's production company], and I went over and said, "I'd like to speak to Mr. Ford if he has a moment." I was shown in, and we chatted a few minutes, and I said, "Well, Mr. Ford, I know you're busy, but I was just wondering if there's anything in the film I could do for you." He said, "Well, you know, doggone it, I just hired a guy, his name is…oh, uh…" He went through a bunch of sounds that finally led me to say, "Are you thinking of William Holden?" He said, "It's William Holden." He had more fun than anybody. So there was nothing for me in the picture; Bill Holden had beaten me to the part.

Barrier: Looking back to Them! [1954], you're very good in your little part in that picture, but you're not Davy Crockett, and I wonder if you knew what it was about your performance in that picture that led Walt or whoever it was to say, "This is the guy we want."

Parker: I really don't know. I think maybe the accent, the unsophisticated sort of appearance. It was determined by one of the casting directors who called me. I was on location, making a film for the Navy medical department on battle fatigue, in southern California at Camp Pendleton or someplace, and the casting man called me. He said, "You're a featured player, and I know that you don't want to do day work, but I have a part that I think would be good for you." I said, "If you think it would be good for me, I'll do it." I didn't know what it was. And sure enough, I had no idea how good it would be. If Walt had taken a phone call or lit a cigarette or sneezed, I wouldn't be talking to you today.

Barrier: And Walt himself was the one who saw you and singled you out.

Parker: Yes, he said, "Who's that?" It wasn't as if he was screening the film to find anybody. I think he was looking at Jim Arness as a possibility, but I think he got interested in the little story, and just happened to stay long enough to see that.

Barrier: You've mentioned Bill Walsh very favorably, and I was wondering what you could tell me about him, as somebody you worked with and whose work you admired.

Parker: Bill was an orphan and was raised in Cincinnati, in an orphanage. Then he got a chance to go to a junior college or something there. Barbara Stanwyck and Frank Fay came through town with a theatrical company, and he was interested in that, and went down and offered to help on the setup and so forth. By the time they finished their engagement in Cincinnati, they were interested in Bill and invited him to come along with them. That's how he got out into show business. He did a lot of things before he became a producer; he worked as a publicist for a firm called Maggie Ettinger, one of the top Hollywood firms. Then, his sense of humor and his ability to write led him to be one of the writers for the Edgar Bergen show. The years went by, and somehow or other he got connected with Disney. Anyway, Walt Disney told him he wanted him to produce a movie—I think it was The Littlest Outlaw. He told Walt, "I don't know if I can do this," and Walt said, "Well, there's no time like now to find out." Bill did a nice job on it, and when Davy Crockett came along, shortly thereafter, he made him the producer.

He was the all-time dollar producer, until Star Wars, in motion-picture history. His pictures were the mainframe, or the guts, or anything you want to say about the Walt Disney film successes from the middle fifties [until the late sixties]. He was my best man at my wedding, and his wife stood up with my wife. Bill was a very complex man, and everybody that knew him felt attached to him. There's not that many of us any more, but when there were more, whenever we'd be together a lot of our conversation would be about Bill Walsh, because he was still fascinating to all of us.

Barrier: Of course, he died prematurely, and I've heard references to how much stress he was under, in the position he was in, being in many respects Walt's right-hand man in that period. It was a hard life for him. Is that what you observed?

Parker: When Bill was really frustrated, this was the way he expressed it: "Hoo, boy!" [in an exasperated tone] That was about it.

Barrier: That was brought on by Walt?

Parker: I used to hear Bill say, "Walt came in in his bear suit today." They were quite a team, and they worked extremely well together. There were other Disney producers, but none of them approached Bill's success, picture after picture.

Barrier: I was doing some time comparisons, and I realized that first Davy Crockett show, which had such a tremendous impact, aired on December 15, 1954, exactly a week before 20,000 Leagues under the Sea opened. That was Walt's first big live-action picture, with real movie stars in it and a very large budget for the time, and it was a successful picture. But evidently Kirk Douglas was not the easiest person to get along with—

Parker: I believe that's an understatement.

Barrier: Douglas himself wrote in his autobiography that he wound up suing Walt because he didn't like Walt's using some footage of him and his sons on Walt's train in his backyard on the Disney TV show. Clearly, the impact of the Crockett show was your impact—people were responding to you in that title role, more than anything else about the program—and, as I've said, it has puzzled me that Walt didn't take advantage of your movie-star qualities in a way that would have made sense for both him and you. I wondered if some of his experiences in dealing with Kirk Douglas and 20,000 Leagues had some backlash on you. Did you ever have any hints of that?

Parker: No, I didn't. Your question about why they didn't give me strong material—frankly, I think attention was split between the development of Disneyland, which was still in its infancy, [and TV and movies]. Walt hadn't expected television to have the impact that it did. I don't know why he didn't, but none of us did, as far as I know. Then they decided that if their merchandising program was a log fire, they were just going to throw another log on, and that was me. They sent me all over the country.

The merchandise thing didn't quite work out as advertised. Walt had given me 10 percent of Walt Disney Davy Crockett merchandise, but then they had run into legal problems because they didn't have the [exclusive] rights to [the Davy Crockett name]. The rest of the world decided, forget the rights, we're going to make it, sue me. There were hundreds of products. So the followup was very weak.

Westward Ho the Wagons! was not a good presentation. I was very grateful for the paycheck and the opportunity, but—I hate to say this—I was not sufficiently understanding [of] the business I was in. If you grab the brass ring once in a career, that's wonderful. If you grab that brass ring and do some followup and some growth in the industry, that's really what everybody hopes for. I guess when I saw that I was just going to sort of do the same thing all the time, I bought a sailboat and went sailing. When it was time to work, I'd come back and do that.

Barrier: At the time they put you into Westward Ho the Wagons!, was it up in the air as to whether it would be for theaters or TV, or did they start with the idea that it would be for TV?

Parker: They couldn't make up their minds exactly what they wanted to do with it. Bill Beaudine was a fine old gentleman, but, basically, he wasn't much help. He just set the scenes up and we shot them, and that was that. Walt never had strong people; he didn't want any strong people.

Barrier: I get the impression that a lot of the directors at Disney were basically mechanical directors whose real skill was in setting things up so that scenes worked on the screen and the actors didn't get in each other's way.

Parker: I think Walt was a counter-puncher. My impression is that he wanted to reserve the right to counter-punch with any effort that showed up in the screening room. He obviously had a great sense of story, in things he was interested in, and was quite a fine actor, if you listen to the people who worked closely with him. But I saw people come to the studio, people he'd hired to do huge, difficult projects, who had never done a simple project. Larry Watkin, the producer of The Great Locomotive Chase, [is a good example]. There were two companies shooting at the same time on a distant location. Peter Ellenshaw, the artist, was directing a second-unit company. He had certain things that he had to do from a matte standpoint, so he was out there with a second unit.

Barrier: Making sure that they were shooting things so that he would be able to put the mattes in.

Parker: Yes. This was a huge undertaking. A narrow-gauge railroad—and let's just say that when you run a horse through a scene, it's pretty easy to turn around and do it again. But when you've got a train, it's a little more complicated. It was a pretty dull picture. As a matter of fact, it was my Waterloo, I think. If I thought of myself as an arrow, I'd stopped heading up and started heading down with that picture. I was put in a role of being pursued and caught and hung.

Barrier: It flabbergasted me when I thought about that. Here's their new star, and they have him hung at the end. I can't imagine what the thinking was that led to your being cast in that part in the first place.

Parker: I had a friend, now deceased, whose name was Burt Kennedy. Burt was a writer and director and a close friend of mine at the time. I showed him the script, and he said, "Oh, my God! This has got a lot of problems." He spoke to some of the things that we've alluded to here, relative to the film. I didn't speak to Mr. Disney about it until we were on location, or on the way to location, somewhere before we actually started to shoot, and I mentioned something about the script, and he said, "No, this is what we're going to do." No discussion. And it was too late; he was right about that.

When I did Davy Crockett, I had an opportunity that I didn't understand. And that was [predictable], because things got a little unique. Burt Kennedy came to me and said, "Fess, you need me to be your manager. And I'm willing to do that." I thought about it, and I didn't know what he meant, really. I didn't quite understand the role that he foresaw. It's interesting, the last conversation I had with him before he died [in 2001], I went down to his birthday party, at his house in the Valley, and he said to me something like, "We should have made a picture." I said, "Well, Burt, I agree, but we'll probably have to put it off until we're on a bigger stage." But he knew what my strengths and weaknesses were, because we had been friends from the day I first worked in films. I'd met him in the fall of 1950, when I was going to school at USC, and his girlfriend had a little sister that I became acquainted with. That's how I met Burt. Later, I moved to an area that was very close to where he lived, and we used to spend the mornings drinking coffee and reading the Daily Variety and talking about pictures and directors and so forth. He was very astute. He was born in a trunk; his family was in vaudeville.

Barrier: You've mentioned that you were under personal contract to Walt. Was that a typical arrangement?

Parker: As far as I know, I was the only person he ever put under [personal] contract.

Barrier: Why did he do that, as opposed to putting you under contract to the studio?

Parker: I really don't know. And when I asked for 10 percent of the Walt Disney's Davy Crockett merchandise, he gave it to me.

Barrier: But that didn't translate into much money.

Parker: No, it did not. When I asked for more money, the late Ray Stark was my agent. So there was the contract I had with Walt, and then a new contract. Things were changed and deals were struck in my behalf that I think basically eliminated their requirement to pay me that 10 percent. I really wasn't aware of it at the time, or if I was, I can't remember it. My background in the film business was very shallow. I was playing very small parts; they were getting better, but they were small parts. I wasn't immersed in the culture.

Barrier: So you simply didn't have the background to be fully aware of all the subtleties that were involved in such negotiations.

Parker: No, but it's not a big deal. I was out on my sailboat, and I wasn't thinking about it too much. I can't buy back that time; I enjoyed it.

Barrier: You worked with Michael Curtiz on The Hangman [1959] after you left Disney, and I guess the other two major films you made at Paramount were The Jayhawkers [1959] and Hell Is for Heroes [1962]. The Jayhawkers is historically kind of crazy, but you're awfully good in it.

Parker: It was hard to understand that picture. Mel Frank was basically a writer-producer, and he finally decided he wanted to direct the film. We had a man on the set, constantly, who was his mentor and really was directing behind the scenes. I'm trying to think of his name. He should be listed somewhere [in the screen credits] as an advisor, or something.

Barrier: You were working not only with stronger directors than you had at Disney but also with stronger actors opposite you. People like Jeff Chandler and Steve McQueen. When you were making those later features, what stands out in your mind as being most different from your work at Disney?

Parker: It was similar to Disney in that Y. Frank Freeman owned Paramount, and he used to invite me in, and we'd sit and talk. The old gentleman who was about 90 years old, Adolph Zukor, would be sitting around during these conversations. Clearly, they saw me as in sort of the Dean Martin role, playing the second man. Which was OK; that was fine for me. I enjoyed Robert Taylor and Jeff, and I found that working with Steve McQueen was the most interesting. I didn't have a lot [of scenes] with him, but I was very comfortable. He seemed to always work within himself, but in my brief scenes with him I felt that we [worked well together]. With Jeff Chandler, bless his heart, we went six, seven, eight takes every scene that we were together. During the fight that we did in the bar, he nailed me with a punch and I had to go get a couple of stitches over my eye. I didn't realize what great pain he was in. Shortly after that, he had this operation; his back, evidently, was really bad. [Chandler died after back surgery in 1961.]

I tend to be fairly steady with dialogue. Finally we came to a Friday night, everybody was trying to leave for Palm Springs or wherever they go, and we were doing this scene, and all of a sudden I had a problem. We probably did twelve or thirteen takes, and the tension gets greater and greater when you get into that circumstance. Jeff was gleeful: "You son of a bitch! You finally blew it!" We had a good time. Norman Panama [Melvin Frank's co-producer] had us to his home for dinner, and Jeff was there with Esther Williams, and she made quite an impression.

Barrier: You didn't make that many films with Paramount…

Parker: No, that was it, in four years.

Barrier: It seems strange, again, that they didn't put you in more things. Was it because westerns were petering out at that point, and you seemed like a natural western star?

Parker: I think something was happening in the ownership. I always suspected that Y. Frank Freeman's son was the person who urged his dad to buy his company. I got the feeling that the movie side of the business kind of went on—Mr. Freeman approved things, obviously, but by the time I got there, he was not a young man. I think they were just kind of running it as a business, which is sort of unusual. With Hell Is for Heroes, all of a sudden there was an edict that there would be one or two more days, and that's it. So we didn't finish the script. My scenes that made sense for me to be in the movie were never shot. All of my gut-impact material was at the end of the picture, with incoming troops relieving our group. There was a nice tie-up.

Barrier: The film does end abruptly. I hadn't really thought about that, but it does come to a stop quicker than you expect it to.

Parker: That was the business side of it: no more money in this film.

Barrier: Talking about the directors, though, like Siegel and Curtiz—on the evidence of their films, they were much stronger directors than the people you worked with at Disney. What difference did you feel, as an actor, in working with directors like these?

Parker: There wasn't any real difference except in the case of Mel Frank, with the man who was constantly observing the scenes. Curtiz was surprisingly easy to get along with. He had such a reputation as a character, but there were no problems. Tina Louise was with Robert Taylor, and Robert Taylor was a very pleasant man. He had a reserve about him, but he wasn't unfriendly, he was just sort of a man who was smoking himself to death.

Barrier: What about Don Siegel? I read somewhere recently about Hell for Heroes that some of the actors had trouble taking it seriously.

Parker: Don Siegel seemed to me to have the old Hollywood mantra down: stick with the money [that is, give the most attention to the highest-paid stars]. He was competent, but as far as his giving me any sort of directions or instructions or help as a director, none. And that's usually the case. There are some people who do try to lead or suggest or something, but most of the time, if the scene works, the good people let you bring what you bring. And if it's obviously wrong, they'll tell you.

Barrier: So you never really had the chance to work with a director—

Parker: I'll be honest with you. I don't think I was ever challenged. I just kind of walked through everything.

Barrier: It has always seemed to me that there was a lot more you could have done if somebody had been smart enough to ask you to do it.

Parker: I wanted to do something that would move me along and mature me in the business, but at a certain point—when I went into Daniel Boone, I felt that the opportunities that lay out there in the future [would grow out of] that show, that there was little that I could expect [from continuing to work in feature films], so I just decided to leave.

Barrier: Did you have any contact with Walt after leaving the Disney studio?

Parker: I saw Walt Disney pretty much as a father figure, and I hated parting on the basis that I did. When I ended up doing Daniel Boone, there was an NBC affiliates' meeting at the Hilton Hotel in Beverly Hills, and there was a cocktail party prior to the dinner. NBC wanted The Further Adventures of Davy Crockett, which I thought I had to consider, because I had a family by that time. Walt had the number one show on NBC, and he said, "No, I own five one-hour films of Davy Crockett, with Fess in them, and I don't want to see that." NBC had that frontier mode in mind, so they said they'd like to have me consider Daniel Boone. Maybe I'm the first guy in the actors' witness protection program. I put on the cap, and I said, "My name is Daniel Boone, and this is my wife, and my children. I live in Boonesborough, a far piece from here." Well, thankfully, the American public sees entertainment for what it is, it's entertainment, it's not life, so we were able to spend six years on it.

Barrier: On the Disney TV show around 1960, there was a Daniel Boone series with Dewey Martin—

Parker: A good friend of mine.

Barrier: I remember looking at this and thinking that it was something that should have had Fess Parker cast in the role. I didn't think Dewey Martin was convincing as a frontiersman. Was that something that was being talked about before you left?

Parker: No, no.

Barrier: So did you have an encounter with Walt at this affiliates' meeting after you had undertaken to do Daniel Boone?

Parker: Yes, the pilot had been picked up, I was going to go on the air with Daniel Boone, and there was a cocktail party. I didn't know he was in the room. I was standing talking to someone, and I felt someone tap me on the shoulder. I turned around, and it was Walt. He said, "I just wanted to wish you well on your new series. Say hello to Marcella." I said, "Is Mrs. Disney with you?" He said, "Yes, she's right over there." I said, "I'd like to go over and say hello to her." And I did. To me, that was like reconciling with my father, in a way.

Barrier: Was that the first time you'd seen him since you left the studio?

Parker: Yes.

Barrier: Did you ever see him again, or was that the only time you saw him?

Parker: That was the only time I ever saw him.

Barrier: Did you ever have any contact with him by letter or phone?

Parker: I don't think so. I don't recall if I did. I don't know on what basis I would have had a [telephone] conversation with him.

Barrier: Speaking of Walt's not wanting you to be Davy Crockett on that NBC show, there was this Bob Hope movie called Alias Jesse James [1959] in which you appear uncredited in one scene. You're not identified as Davy Crockett, but you're clearly supposed to be Davy.

Parker: That was when I was over at Paramount. Bob Hope gave me a diesel engine for that moment. I guess he thought it would be good for my sailboat, or something. My agent had purchased the African Queen [the boat used in that movie] and made it into a little yacht. I never realized, until maybe right now, that the fact that I got a diesel engine was kind of suggested by my agent, who probably knew that I didn't have any place to put that engine. So it ended up in the African Queen.

[Posted December 20, 2004; corrected December 23, 2004]