ESSAYS

[I spent most of June 2004 in Europe, visiting people and places associated with Walt Disney. I also spent a couple of days at the animation festival at Annecy, France. I'm writing about that trip, which took me to Switzerland, Denmark, and England as well as France, in several installments. MB]

European Journal

II. Annecy

At almost the last minute, Phyllis and I shaved time off our stays

in Paris and Switzerland so we could add two nights at the Annecy

International Animated Film Festival to our itinerary. We had

been to the town of Annecy before, spending one rainy night there

in 1995 after visiting John

McGrew, but I had never before attended the festival. "The

films are not worth the trip," an animator friend told me,

"but the town is." The town's attractions were obvious

in 1995, even in the rain—Annecy sits on a beautiful lake,

looking out over the French Alps, and at its heart is a picturesque

"old town"—so I was sure a visit there would not

be wasted even if the festival disappointed.

As

it was, I wound up wishing I could have spent more time at the festival.

I'm not sure that I would ever want to devote a full week to it,

but a day and a half clearly wasn't enough. I saw only a sampling

of the short films in competition (and missed the surprise winner

of the grand prize, Mike Gabriel's Lorenzo for Disney) and

only one of the five competing features. I had lunch with Amid Amidi

and Will Ryan, and met Bill

Plympton, but I didn't get to see nearly as many people as I

would have liked.

As

it was, I wound up wishing I could have spent more time at the festival.

I'm not sure that I would ever want to devote a full week to it,

but a day and a half clearly wasn't enough. I saw only a sampling

of the short films in competition (and missed the surprise winner

of the grand prize, Mike Gabriel's Lorenzo for Disney) and

only one of the five competing features. I had lunch with Amid Amidi

and Will Ryan, and met Bill

Plympton, but I didn't get to see nearly as many people as I

would have liked.

Despite the large number of festivalgoers from other countries, Annecy is unmistakably and almost defiantly a French event. Signs in English—and convention employees speaking more than an approximation of English—were relatively scarce, and there was barely a nod to other languages. Perhaps Mifa, the animation marketplace that ran alongside the festival proper, was slicker and more international in flavor, but I never got there.

The three film programs I attended opened with clever animated festival "bumpers" that the audiences greeted raucously, like old friends. When the second program devoted to shorts in competition was late in starting, the theater filled not just with catcalls but with paper airplanes—just what you'd expect from a festival by and for cartoonists.

Most of the shorts in the program were a letdown compared with the entertainment provided by the audience and the bumpers. I did enjoy a two-year-old American computer-animated cartoon, Carlos Saldanha's Gone Nutty for Blue Sky Studios, which I'd somehow missed before. It's a much better film than Blue Sky's feature Ice Age, in which the character Skrat was introduced. The most intriguing entry, though, was Marc Craste's Jo Jo in the Stars, a British film—in black and white!—that uses computer animation to create a bleak and mysterious world. If Tod Browning were to return to life as a computer animator, he'd probably make films like Jo Jo.

The next day, I had just enough time before my train left for Geneva to see part of the third shorts program. Like the second program, it included one good American cartoon—Mark Kausler's It's the Cat, an expert recreation, set to a song from the early thirties, of what is most enjoyable about the free-flowing Hollywood cartoons of those years. Kausler's cartoon got only a tepid response from the apparently baffled audience. There was much more enthusiasm for the film that followed, Through My Thick Glasses, a clunky Norwegian-Canadian clay-animation effort about the Nazi occupation of Norway. (Glasses wound up receiving an award for "special distinction.")

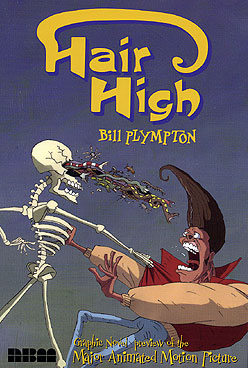

Even

though I saw only one of the five feature films in competition,

that was the only one I wanted to see, Bill Plympton's Hair

High. The other four sounded—and, to judge from stills

and posters, looked—variously dull or awful, or both. (A South

Korean feature, Oseam, won in the feature category.) Is it

even possible, I wondered, to make good short animated films when

the feature form is artistically moribund? Most of the shorts I

saw at Annecy could be taken as evidence that it is not.

Even

though I saw only one of the five feature films in competition,

that was the only one I wanted to see, Bill Plympton's Hair

High. The other four sounded—and, to judge from stills

and posters, looked—variously dull or awful, or both. (A South

Korean feature, Oseam, won in the feature category.) Is it

even possible, I wondered, to make good short animated films when

the feature form is artistically moribund? Most of the shorts I

saw at Annecy could be taken as evidence that it is not.

I've never been quite sure what I think of Bill Plympton's films. I remember very well how astonished and delighted I was by one of his first shorts, Your Face, when I saw it in the late eighties, and I've always been impressed by how fecund and inventive Plympton is. He came to animation relatively late, in his mid-thirties, but he mastered the medium with impressive speed. His films, unified as they are not just by a drawing style but by his own drawings—the animation is entirely his—are personal as few others are. But my interest in his films has waxed and waned; something has always made me question my enthusiasm for his work, and I can't claim to have followed his career as closely as I might have.

Finally, when I saw Hair High at Annecy, I figured out what was bothering me. A clue lay in Plympton's identification of his cartoon as a "gothic comedy." "Gothic" it is, I suppose, for reasons suggested by a summary of the film in Annecy's program guide: "the legend of Cherri and Spud, a teenage couple who are murdered on a prom night and come back to life [as skeletal remains] a year later."

The problem with the "gothic" emphasis is this: until the gruesome business at the end, Hair High has been for most of its length a sharp and funny comedy, set at an early-sixties high school, and a wonderful showcase for Plympton's genius at translating mental states into startling but invariably apt drawings. There has been nothing "gothic" about it.

Things go wrong in revealing ways, though, even before Cherri and Spud are murdered by Rod, Cherri's jealous boyfriend. There's graphic and painful violence when Rod pries loose a stooge's fingernail, and again when another stooge's eyeball is pierced. Blood flows, as if to question Plympton's renderings, in most of the film, of a reality that is far more emotional than physical.

In Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, I describe the great achievement of Disney animation in the late thirties as its bridging of the gap between "inner" and "outer," so that cartoon characters were for the first time wholly present on the screen, both physically and emotionally. I write of Bill Tytla's animation for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: "Whatever passed through Grumpy's mind, it seemed, was simultaneously visible in his face and body, through acting of a kind that was possible only with a cartoon character."

As long as "inner" and "outer" are unified in this way, a cartoon maker has a great deal of leeway in choosing what to emphasize. What makes Bob Clampett's Warner Bros. cartoons so thrilling, for instance, is that what's on the screen is almost entirely "inner," an animated equivalent of the tumultuous human psyche. What I see in the best Clampett cartoons, filled as they are with fluid movement and expressive distortions, is what the French philosopher Diderot wrote about more than 200 years ago, when he described the human mind as "awash with many images, many excitements, merging fears and fantasies that dissolve into one another."

In the features from the Disney studio and its imitators—and in computer-animated features like Pixar's—animation has evolved in a very different direction. It has been increasingly concerned over the decades with the "outer," in the form of literal movement and realistic drawing. Even the animation of those characters drawn in a true cartoon style has tended to slide into formulas that nod toward individual expression without providing any of it. As dreary as it is, such animation has somehow become the standard against which other kinds of animation are measured and invariably found wanting.

At some level, I'm afraid, Plympton has bought into the "illusion of life" humbug that long ago robbed the Disney features of their vitality. Plympton is very much an "inner" sort of animator, one who is almost totally concerned with bringing to the screen what is going on inside his characters' heads. At critical points, though, as if bowing to the Disney line, he asserts the supremacy of the "outer," in the form of the harshest sort of physical reality, and thus denies the validity of exactly what has made his characters so interesting. When he pulls off a fingernail in excruciating close-ups, or murders his hero and heroine for the sake of grim jokes at the senior prom, he mocks his audience—and himself.

John Kricfalusi, that most vociferously anti-Disney of Hollywood cartoonists, has done very much the same thing in his most recent Ren & Stimpy television cartoons, dominated as they are by disgusting images. Like Plympton a brilliant "inner" sort of animator, Kricfalusi has also erected imposing obstacles between his characters and his audience, in effect conceding the whole vast domain of character animation to his self-proclaimed enemies. What sad, strange victories for the forces of dull, lifeless animation.

In short, I didn't come away from Annecy filled with high hopes for the future of animation. But I came away thinking I had at least glimpsed the future, and that's enough to make me want to go back to that lovely town and its fascinating festival.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[Click here to read the first installment in this journal, about Disneyland Paris, the third installment, about the Swiss village of Zermatt, or the fourth installment, about Copenhagen's Tivoli Gardens.]

[Posted July 21, 2004]