COMMENTARY

Lookin' Good

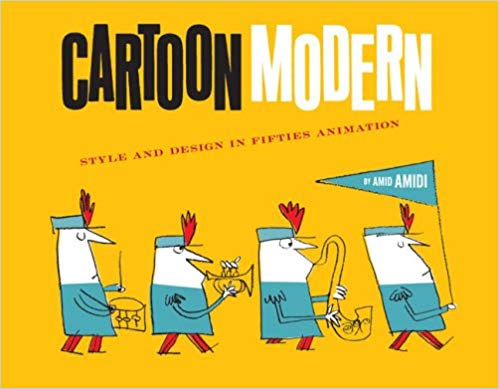

In

his beautiful new book, Cartoon

Modern: Style and Design in Fifties Animation (Chronicle

Books), Amid Amidi writes about theatrical shorts, industrial films,

TV cartoons, and commercials whose makers sought large popular audiences

even as they embraced the tenets of modern design. Those filmmakers

rejected realistic illusion in favor of a frank acknowledgment of

the two-dimensional surface, and they used color, texture, and line

in ways that called attention to the elements that made up their

films.

In

his beautiful new book, Cartoon

Modern: Style and Design in Fifties Animation (Chronicle

Books), Amid Amidi writes about theatrical shorts, industrial films,

TV cartoons, and commercials whose makers sought large popular audiences

even as they embraced the tenets of modern design. Those filmmakers

rejected realistic illusion in favor of a frank acknowledgment of

the two-dimensional surface, and they used color, texture, and line

in ways that called attention to the elements that made up their

films.

Amidi devotes chapters to individual studios, rather than individual creators, and those chapters are arranged alphabetically; there's no overarching narrative. That makes for a certain awkwardness when you're trying to follow the career of a major creator like John Hubley, but the advantages far outweigh such minor inconveniences. The studios often did have distinct personalities—some very attractive, others less so—and they emerge clearly through Amidi's lucid descriptions and his excellent choice of illustrations.

I was struck, though, by how cool and bloodless Cartoon Modern sometimes seems. If a CD came with the book, it would have to be filled with "West Coast jazz," the oh-so-hip, low-temperature music, by the likes of Shelly Manne and Bud Shank, that was contemporary with the films. (As Cartoon Modern reminds me, animation artists like Hubley and Paul Julian drew a lot of jazz album covers in those days.) It's a little jarring when a hint of real conflict slips in, as with Amidi's account of Ray Patin's disdain for the modern design his employees espoused, or when the late Jules Engel dismisses Chuck Jones's wonderful layout artist Maurice Noble as unworthy of a place at the UPA studio, where Engel was a background painter.

Engel was, over the years, the noisiest advocate for the superiority of UPA and the kind of modern design that found its purest expression in the UPA cartoons. For all of Engel's boundless self-esteem, some people at UPA—Paul Julian, a vastly superior artist, comes immediately to mind—regarded him at least as skeptically as Engel regarded Maurice Noble. There are few hints in Cartoon Modern of such continuing conflicts at UPA and other studios, conflicts that sometimes involved personal animosity but were more often rooted in serious artistic differences. Instead, the overriding sense in the book is of gentle artists, serenely pursuing their personal visions and pausing occasionally to cluck admiringly over the work of fellow geniuses. I have to wonder if Amidi's apparent reluctance to write about artistic conflict reflects not so much the animation industry of the fifties as it does today's industry, whose prevailing tone seems to be a smothering coziness (why bring up artistic differences when so few artistic decisions are being made?), punctuated by spasms of savage resentment.

Not all of the artwork in Cartoon Modern invites admiration—surely it was Igor Stravinsky's involvement that recommended Fine Arts Films' misshapen drawings for Petrouchka—and some studios and artists seem over- or underrepresented, owing in many cases, I'm sure, to whether artwork did or did not survive. (The Jay Ward studio, for one, is conspicuously absent.) But overall, the illustrations are remarkably handsome—clean-limbed, stylish, and smartly colored. To make them look even better, Amidi shamelessly stacks the deck against traditional cartoons of the Disney/Warner Bros. kind, holding up a 1934 Van Beuren model sheet as an example of what Cartoon Modern's heroes were rebelling against. But everything that came out of the Van Beuren studio was retrograde as soon as it was drawn, and that simply wasn't true of Disney, in particular, where the evolution of design in the late thirties—of characters and then of backgrounds—was incredibly rapid.

There was no comparable evolution at the modern-design studios in the fifties, but there didn't need to be, because modern design's advocates had so many good sources to borrow from. The Disney people always borrowed, too—as Amidi points out—but there was no way they could borrow what they most wanted: convincing movement, characters that invited a suspension of disbelief, emotionally grounded stories. Their intense searching for those things made the last half of the thirties and the first few years of the forties the most exciting and dramatic period in animation's history. Nothing comparable happened in the fifties, as becomes clear whenever Amidi discusses the cartoons' attributes apart from their design. At one point, he persuasively distinguishes the stylized animation employed in the better fifties cartoons from TV-style limited animation, but he simply doesn't have much to say about what such stylized animation, and the modern design it complemented, was for—that is, what purposes modern design served that couldn't have been served in any other way, or at least not as well.

He is mute with good reason. Most of the cartoons he discusses don't hold up under that kind of scrutiny. He writes of a "broadened scope of subject matter ... when artists began using the medium to not only create entertainment films, but also help sell products, educate audiences about political and business ideas, and express personal views," but that list—"business ideas"?—speaks to me more of cramped ambitions than expanded opportunities. Many modern-design films of the fifties, like Ward Kimball's outer-space TV shows for Disney, are now historical curios; all but a few of the vaunted UPA shorts resist characterization as anything but insipid children's films; and so on. The only features that Amidi discusses, Sleeping Beauty and One Hundred and One Dalmatians (not 101 Dalmatians, as Amidi has it) were made by Disney, where there was never any sustained commitment to modern design. UPA made a feature, 1001 Arabian Nights, or two, if you count Gay Purr-ee, but Amidi says nothing about either—understandably, if you've seen the films.

What ultimately matters to Amidi, as it mattered to most of the artists he discusses, is simply how good the cartoons looked—modern design as an end in itself. But modern design was derivative; it owed its existence to works of art, by masters like Picasso and Matisse, that had far more intellectual and emotional depth. It couldn't stand on its own. There's no denying that a lot of fifties cartoons looked very good indeed, just like the snazzy cars—those sleek land-boats with their arrogant tailfins—that many of the cartoonists drove. But where the cartoons were concerned, there was too often nothing under the hood.

John Hubley, had he continued in charge at UPA, might have enlarged on what he did in Rooty Toot Toot; he might have married inventive modern design with adult subject matter in cartoons that were more exciting than anything that actually reached the screen. But, like his colleagues, Hubley might just as well have been defeated by Columbia Pictures' demand for more Mister Magoo shorts. As it happened, modern design dried up as a fertile source of ideas in only a few years. It was like the rains that produce a staggering abundance of colorful flowers in Texas's Big Bend country each spring; then the flowers die, leaving behind only the desert—in my analogy, the wasteland of the sixties, with its mechanical TV shows and deadly dull Disney features. But the flowers were indeed lovely, and considering how disappointing the films of the fifties can be, Cartoon Modern is perhaps the best way to enjoy many of them. Anyone who cares about Hollywood animation's history should buy Amidi's book without hesitation.

[Posted September 18, 2006]