"What's New" Archives: 2020

September 14, 2020:

June 5, 2020:

February 11, 2020:

September 14, 2020:

Onward

I just missed this latest Pixar feature when the pandemic closed theaters last March, but thanks to Disney + (yes, I've subscribed, how could I resist) I've now seen it twice. This is Pete Docter's debut feature as John :Lasseter's successor as Pixar's creative head (the Pixar veteran Dan Scanlon directed), and I wish I could recommend it. The disabling problem is the fundamental: miscasting, not of the voice actors, who are OK, but of the characters themselves, and the roles they're assigned in the story. Ian, the younger of two elf brothers and the central figure in the quest that passes for a plot, is simply too weak a personality to bear the load he has been assigned, and his older brother, Barley, is too shallow and noisy to take up the slack. Flip the two characters, though, so that Ian is the older and more mature of the brothers, and Barley the reckless kid brother, and you might have something. Instead, we have Ian's constant whimpering and Barley's feckless swagger, with not enough comic support in the writing for either brother.

A pity, because the basic conceit—the world of the film is the world of classic mythology, corrupted and diminished not by some breach of divine law but by electricity and its conveniences—is perfectly workable. Little unicorns rooting in garbage like alley cats, a manticore (voiced wonderfully by Octavia Spencer) as the proprietor of a Chuck E. Cheese-lookalike, biker sprites, and so on--all this works, for me, as a sort of degenerate version of the Pastoral Symphony in Fantasia, just not well enough to make up for the fundamental mistake.

At least Onward isn't, not quite, a victim of the religiosity that has infected other Pixar features and dominates the dreadful creationist fable The Good Dinosaur. Onward is, by default, a pagan story; that's what you get when you stir elves and other rmythical creatures into a plot that turns on the boys' efforts to resurrect their dead father (a victim of cancer, that least amusing of diseases) for twenty-four hours. Their task is complicated by the failure of a magical staff to retrieve more than the lower half of Dad's body from whatever afterlife he is now inhabiting. Where has he gone, and to where is he returning? What would it be like to have a dead parent reappear? The film doesn't tell us; we get only a long-distance view of Barley talking with his father before Dad returns to wherever he has been. In other words, Onward dodges the questions that might--but, granted, probably wouldn't--have made it worth watching. I hope for better from the next Pixar feature, Soul, but the previews, dwellling as they do on the afterlife and inviiting comparisons with the likes of Coco, are not

June 5, 2020:

Raskolnikov's Dream

It has been almost four months since I last posted here, a period that I've devoted in part to reading (in Sidney Monas's translation) the great 19th-century Russian novel Crime and Punishment, by Fyodor Dostoyevsky (at the right). While sick, he had dreamed the whole world was condemned to suffer a terrible, unprecedented, and unparalled plague, which had spread to Europe from the depths of Asia. Except for a small handful of the chosen, all were doomed to perish. A new kind of trichinae had appeared, microscopic substances that lodged in men's bodies. Yet these were spiritual substances as well, endowed with mind and will. Those infected were seized immediately and went mad. Yet people never considered themselves so clever and so unhestitatingly right as these infected ones considered themselves. Never had they considered their decrees, their scientific deductions, their moral convictions and their beliefs more firmly based. Whole settlements, whole cities and nations, were infected nd went mad. Everybody was in a state of alarm, and nobody understood anybody; each thought the truth was in him alone; suffered agonies when he looked at the others; beat his breast; wept and wrung his hands. They did not know whom ro bring to trial or how to try him; they could not agree on what to consider evil, what good. They did not know whom to condemn or whom to acquit. People killed each other in a senseles rage. Whole armies were mustered against each other, but as soon as the armies were on the march they began suddenly to tear themselves apart. Their ranks dispersed; the soldiers flung themselves upon each other, slashed and stabbed, ate and devoured each other. In the cities the alarm bells rang for a whole day. Everybody was called, but nobody knew by whom or for what, and everybody was on edge. ... Fires blazed up; hunger set in. Everything and everybody went to rack and ruin. There is more in the same vein, but you get the idea. You may detect a resemblance between the dream and our current state of affairs, the dream lacking mainly an analog to the vicious fraud in the White House.

I'd planned to take Crime and Punishment with me on a birthday trip for Phyllis in March. We were going first to San Francisco, then to Maui for six days, and then back home via Los Angeles (and Sunday dinner with Jenny Lerew at Musso & Frank Grill in Hollywood). Thanks to the coronavirus, the bottom fell out a few days before our scheduled departure, and we felt fortunate to get refunds for most of the cost of the trip.

When not reading Dostoyevsky, and while looking for something to do besides household chores, I've not been watching cartoons. No Disney +, no HBO Max. Instead, I've spent many hours watching the Metropolitan Opera's free streaming of dozens of performances, most from the "Live in HD" series that has been showing in theaters for the last fourteen years or so. Sometimes there's actually a strong cartoon connection (as with a colorful production of Rossini's version of Cinderella), other times there's what strikes me as a cartoon flavor (the first act of the Met version of Verdi's Masked Ball feels like a Talkartoon come to life), and, of course, there's the music from operas that Carl Stallling and Milt Franklyn found so useful in the Warner cartoons.. If you've seen Friz Freleng's Back Alley Oproar, you've heard the famous sextet from Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor, and you are perhaps familiar with a modest Chuck Jones cartoon called What's Opera, Doc? That's a joke, son.

I'm reminded, while watching all these operas (some wonderful and some not so wonderful, but almost all of them worth watching at least once) of how much more of a presence opera and other classical music used to be in American cultural life. But I don't fret much about the lack of interest in the music among many if not most young people; I think it's best to grow into classical music in general, opera especially, and the music will survive even as its audience shrinks and expands.. Me, I'm grateful that the Met has used the pandemic as the occasion for letting me and millions of other people see dozens of operas that I knew only by name, if at all. And yes, I did express my appreciation with a donation to the Met, and I'll send another one soon.

From Robert Holmen: In your recent blog post you commented: "I'm reminded, while watching all these operas... of how much more of a

presence opera and other classical music used to be in American cultural

life." To some extent that was an imposed presence. The people who ran radio

and TV networks programmed classical music to counter the frequent But it was a large presence. I was re-surveying my Mickey Mouse "Treasures" DVDs and re-watched "The Barnyard Concert" (1930). The joke, It occurred to me that "Poet and Peasant" had to have been quite

familiar to the common man back then for Disney and his crew to feel But that would be the situation today. To most people now that cartoon

must appear as just silly animals making odd musical noises. That is a He seems to persist at all only because of his association with cartoons

while the many other light classical composers of his time have vanished I peg the overall fall of classical music from school curriculums and

public life to begin somewhere in the 60s-70s when Holocaust awareness From Kelcrum: Nice to see you're still writing. Your recent post about classical music and opera caught my interest since I work part time at a classical radio station, though not as a musical authority. Growing up, like most kids, I had little use for the classics. It's most often something you appreciate over time. Of course there's a strong cartoon connection and most of us seem to have been introduced to it through cartoons like "What's Opera, Doc", "Convict Concerto" and "Cat Concerto" (which inspired Lang Lang to take up the keyboard). There are many who prefer it as a background medium when they're drawing, painting, working at the office or whatever. Anything with lyrics is likely to distract so it's no surprise that many classical stations play opera sparingly. I often wonder how many fans of "Rabbit of Seville" and other "Barber of Seville" parodies realize the original source was already a comedy. Why take something down a peg when it already has a sense of humor? But even a comic opera has a bit of pretension so it works out. The famous "Largo Al Factotum" piece that gets spoofed in "Off to the Opera", "Musical Maestro" and a bunch of others usually feature a pompous figure doing a stuffy rendition of it as if he didn't have the slightest idea he was doing a musical comedy monologue. This guy's just begging for slapstick comeuppance. It's stuff like this that might make people think that the classics are just museum pieces. But so much of it is still used as background in the movies and television that people respond to it one way or another, so they can have at least a layman's appreciation. And even as a kid I could see that "Rhapsody in Rivets" was on to something. [Posted September 14, 2020] June 5, 2020: My previous post under this title referred to R.C. Harvey's failure to recognize, in his annotations for Fantagraphics' reprinting of the complete Pogo, that George Y. Wells was a real person whose identity was easy to track down, not a name that Walt Kelly made up. There's an even odder annotation in the same Pogo volume, the sixth. Harvey writes, in his entry for December 4, 1960, about the name "Kathleen" (also "Kathe Kelly") on one of Pogo's skiffs:

"'Kathleen' may be a fond Irish recollecton of Kathryn Barbara, Kelly's daughter who died in infancy in the fall of 1952 before reaching her first brthday Biographer [Steve] Thompson explains this poiignant reference ... 'For many years in late October, Kelly would draw a bug floating through the sdwamp with a birthday cake, trying to find someone looking for a birthday." It's no longer 'late October,' but the reference seems a propos. 'S'more' [lettered on the skiff] may be a plea for more time for his daughter, whose shortened name, 'Kathe,' appears with 'Kelly' on the stern of the skiff in the next panel."

The problem here is that "Kathleen" is the name of the eldest of Walt Kelly's three children by his first wife, Helen. As far as I know, Kathleen has never been involved with the comic strip or other Kelly enterprises, unlike her siblings Carolyn and Pete, but to conclude that the name on the boat is not hers but that of another Kelly daughter requires some tortured reasoning, which Harvey unfortunately provides.

{A September 14, 2020 update: I learned recently that Kathleen Kelly, or as she had somehow become known, Kathleen Cassandra Omalley (she never married), died at the age of 72 on October 5, 2015, in Minneapolis, where she was a librarian.]

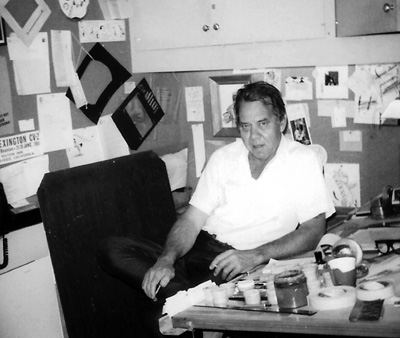

On a more positive note, I can recommend Jim Korkis's essay in the new book about Don Morgan, whom I met at Chuck Jones's Tower 12 studio in Hollywood in June 1969, during my first trip to the West Coast. Don struck me then as an exceptional character, and I think a little of his personality comes through even in my black-and-white snapshot.

February 11, 2020: I'm still studying the latest volume, the sixth, of Fantagraphics' complete Pogo—a classy job, as before—and I'll have more to say about it later, but I can't help but point out an unfortunate mistake on page 327, in R. C. Harvey's annotations of Walt Kelly's references to people and events. In his note for the strip of January 16, 1960, Harvey writes of the name "George Y. Wells," uttered as an oath by the insect mother of the bug candidate Fremount: "George Y. Wells was apparently an entirely fictitious person." Not so; George Young Wells was the editor of the New York Star's editorial page when Kelly was that short-lived newspaper's editorial cartoonist. When Wells died in 1963, at the young age of 55, a full obituary appeared in the New York Times, where he worked after the Star folded. Harvey presumably did not consult the Times, or, for that matter, my book Funnybooks, where Wells turns up a couple of times in the index. No big deal, obviously, but it does seem a pity that Harvey didn't make a greater effort to identify Wells, a former colleague whom Kelly regarded highly enough to honor in his very popular comic strip.

complaints that they were just serving up immoral dreck to the public.

Newspapers were eagerly carrying these complaints almost as soon as

network radio got up and going.

of course, is that they do a very amateurish rendition of Franz Von

Suppe's "Poet and Peasant" Overture.

confident in building a cartoon around it. The joke is mostly empty if

you don't know how the real "Poet and Peasant" sounds.

mark not only of the fall of classical music but of Von Suppe himself.

He has nearly disappeared from the concert repertoire. I can't imagine

any major symphony orchestra programming a Von Suppe overture today on a

regular concert.

completely.Auber, Flotow and Boieldieu overtures were common on New York

Philharmonic programs a century ago. Today... pffft. The orchestra

librarian would probably need a hazmat suit to blow the dust off those

parts now.

went mainstream and people began to notice, "hmmm... all that classical

music that is supposed to make you more civilized sure didn't work on

the Germans, did it?" The halo is gone.How Did That Happen? (No. 4 )

How Did That Happen? (No. 3)