"What's New" Archives: 2019

December 7, 2019:

October 12, 2019:

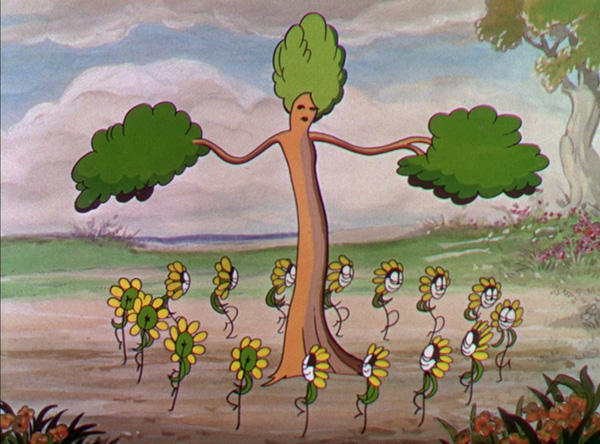

Flowers and Trees in Black and White

September 18, 2019:

August 10, 2019:

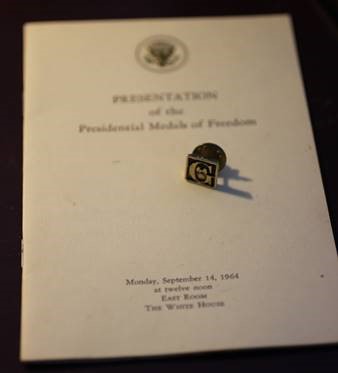

More on Walt's Goldwater Button

August 2, 2019:

More Disney Art Brought Out of Hiding

July 19, 2019:

June 15, 2019:

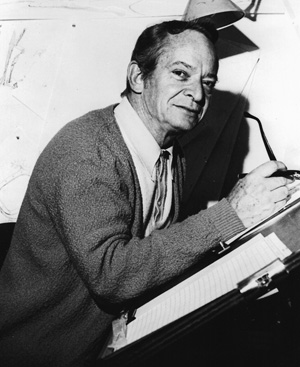

Interviews: Four With Maurice Noble

January 24, 2019:

December 7, 2019:

Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly?

Amazon.com wrote recently to let me know that the sixth volume of Fantagraphics’ reprinting of the complete Pogo has been delayed yet again, this time to mid-January. No great surprise; I think all the previous volumes have been delayed one or more times, mainly if not entirely when it has been difficult to find satisfactory source material. Pogo is always worth the wait, but I’m particularly interested in the new volume, which will cover 1959 and 1960, because of what it might tell us about Walt Kelly himself.

In April 1960, when Kelly made his second visit to the Okefenokee swamp, the Atlanta Constitution mentioned in a report on the visit that he had suffered a heart attack a few weeks earlier, on April 5, and had been hospitalized for ten days. This was one of the first of the serious illnesses that would shadow Kelly until his death in 1973 from the complications of diabetes. We know that later in his life Kelly’s work was adversely affected by his poor health, and I’ve found myself wondering if there’s early evidence of such damage in the mid-1960 strips that will be included in the new volume.

Most comic strips have always been in some sense factory products, so that assistants can fill in when a strip’s originator falls ill or dies. We know that Pogo was different, and always had a much more personal flavor than almost any other comic strip. That personal quality seems to have manifested itself most intensely when the strip was aligned with some darker passage in Kelly’s life.

For example: in early 1950, Kelly exchanged a couple of letters with Charles Thorson, a former colleague at the Disney studio whom Kelly apparently regarded highly. “Everything is fine with us [Kelly and his wife Helen and their three children] here,” he wrote from Connecticut. “We’ve been married almost thirteen years now and I remember a letter from your brother in which he said his wife grew dearer every day—I can say the same—though I am not sure I deserve to since my own native talent and a few lessons from Charles Thorson have made of me a nocturnal bastard of taste and refinement.”

Whatever that last sentence meant, exactly (assuming it was more than tongue-in-cheek joshing), it foreshadowed what happened abruptly about six months later. In October 1950, Kelly got what was from all appearances a Mexican mail-order divorce and married the woman who had been his secretary. The Pogo dailies that he must have produced around that time, for publication in January 1951, are remarkably weak, lacking the overflowing comic energy that makes Pogo at its best such a joy to read. Fortunately, the strip recovered within a few weeks.

I must believe there was some connection between the temporary collapse of the daily strip and the collapse of Kelly’s home life. Such a connection might explain why those 1951 strips were not reprinted, as best I can tell, until they appeared in the second of Fantagraphics’ reprint volumes.

Because Kelly was such a wonderful cartoonist, we need a full biography that would illuminate the connections between his life and work. Does the market exist for such a book? I’m sure the Kelly heirs and their publishers at Fantagraphics have given some thought to that question.

(Thanks to Didier Ghez for copies of the two Kelly letters to Charles Thorson.)

From Galen Fott: I enjoyed your recent post about how Walt Kelly’s personal life affected his work. As a deeply poignant example, I’m sure you’re aware of the death of Walt’s and his second wife’s first child Kathryn Barbara, which I wrote about here: http://blogfott.blogspot.com/2013/03/kathryn-b.html .

The birthday cake bug didn’t appear in 1958; I’m interested to see if Kelly picks it right back up in Fantagraphics’ Volume 6.

MB replies: I'm not yet done reading the new volume, but so far it appears that Kelly did not memorialize Kathryn Barbara's birthday after 1958.

[Posted February 11, 2020]

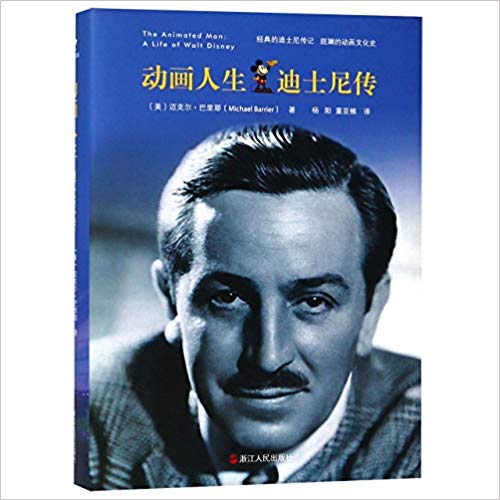

Bookmarks

The Animated Man, my biography of Walt Disney, has received its second translation, this one into Chinese (the first, published a few years back, was into Italian). This is an authorized translation, arranged through my publisher, University of California Press. I don’t expect to realize much financial gain from the translation, but it’s pleasing to have the book more widely available. Now if only some publisher would bring out a French translation; that would be a book I could read, albeit with some difficulty.

The Animated Man also got a nice little plug in The New Yorker, which identified it as one of the two standard biographies of Walt, the other being, of course, Neal Gabler's unfortunate doorstop.

October 12, 2019:

Flowers and Trees in Black and White

Jim Bradrick is one of those people an author cherishes, the people who actually read what that author has written. Jim writes:

I am one of a particular sort of fan of yours—there must be a few hundred of us—who were animators or animation enthusiasts back in the '70s and read avidly your interviews published in Funnyworld and then waited twenty years for your book [Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age] to finally appear. And I was not at all disappointed by your book, though it must have been somewhat vexing for you that in the interim a lot of background material about the Hollywood animation industry had been published, including Illusion of Life, the two Shamus Culhane books, Steve Schneider’s book on the Warners/Schlesinger studios (your own old project revived?), and histories by Leonard Maltin, Charles Solomon, Leslie Cabarga and others, stealing, if not your accuracy of scholarship, at least a lot of your thunder.

Now, twenty years on past that, I am giving Hollywood Cartoons a nice slow re-reading, and enjoying it very much. It is fun to read about The Three Little Pigs or Playful Pluto, for example, and then to go on YouTube and immediately see what Art Babbitt or Fergie did that you were talking about. I know it was not so easy back when you were viewing all those cartoons in your research. I also began by viewing 16mm copies of cartoons on an editor, before even VHS tapes became available. Today I animate on paper but ink and paint digitally and output my work as digital movies, yet I began with cels and cel paint. One TV commercial shoot was almost ruined when a few key cels were forgotten on top of a kitchen refrigerator, where they had been laid out to dry.

And on to the real point of this post. Jim continues, writing about Disney's first three-strip Technicolor cartoon, from 1932:

And speaking of cels and cel painting, I want to mention one particular claim made in the chapter that dealt with Flowers and Trees and its conversion from black and white to color. You quote Bill Cottrell as saying that they washed the paint off the backs of all the cels and then repainted them in color, all without disturbing what was on the front side of each cel. To me, that is a mind-boggling claim. Five to six-thousand cels it must have been! It is true that cels in many studios were washed and re-used; Chuck Jones did it in his first job in the animation industry (at Iwerks), and it was certainly the lowest of the low rungs to be on. But I am very sure that the process must have been by immersion, putting cels by the hundred into a big tub or wash basin or sink, with plenty of running water to constantly wash away all the dissolved tempera paint. But one at a time? Taking care never to get the front side wet? Five or six thousand of them? Not possible. No, any production manager who knew anything would either order them completely washed, or else just have the inkers get busy on new tracings on new cels.

Cottrell was only a camera operator at that time. Perhaps he believed it because someone told him it was so, but I maintain it would have been a crazy thing even to try. What do you think?

Bill Cottrell was not alone in speaking of the washed and repainted cels; Don Graham and Dot Smith, Hazel Sewell's successor as head of the Disney ink and paint department, both mentioned that episode (not to me). That's not decisive, of course; both Graham and Smith could have heard a version at second hand, perhaps from Bill Cottrell. But as to the plausibility of Cotttrell's account, I found this comment from Mark Kausler persuuasive:

In the 1930s, cel paint was water based, not vinyl based. Vinyl paints came in about the late 1950s, I think. The early Cartoon Colour paints were all water based, and Cartoon Colour still makes both "rewettable" and vinyl cel paint to this day. Cels were often washed off one at a time, as the paint would come off fairly easily with water and a cloth. The ink on the front of the cel was a little harder to get off, and often left scratches if the inker used a steel point pen and dug in a little too hard. So I think the story about the cels for Flowers and Trees being washed off without touching the ink seems credible. The BIG clue would be to look carefully at Technicolor prints of Flowers and Trees, and seeing if there are "self" or colored lines on the front of the cels, then one could easily tell if the story were true, since the original cels would have been inked in black line.

So, for the time being, at least, I see no reason to amend or reject Bill Cottrell's account. If you want to read what I say about Flowers and Trees in Hollywood Cartoons, turn to pages 80-81.

[A November 14, 2019, update from Mark Kausler: " I looked at some artwork sites for Flowers and Trees, didn't find much, but did run across some video of F&T showing at slow speed, and couldn't see any color in the outlines at all. So it may be true that the (nitrate) cels were washed off."]

From Peter Hale: There does not seem to me anything odd about a decision to wash-off and repaint the "black-and-white" cels.

Firstly, the film was "in production" when Disney decided to switch to colour so we don't actually know how many scenes had been through 'ink & paint' -- it certainly wouldn't be the whole film.

Normally cel-washing would involve working on one side at a time, wetting the inked or painted area (usually only one character: just a small proportion of the whole cel) then gently scraping and wiping it away. This was done by the lowest-paid workers, and most studio managers considered the practice more cost-effective than purchasing new cellulose nitrate sheets.

The Flowers and Trees cels had been traced by skilled inkers and only the painted side needed cleaning -- only half the work to save the cost of tracing the scenes a second time. I think the Ink and Paint Department would have been the first to suggest this approach.

[Posted January 16, 2020]

From Jim Bradrick: Well, my opinion is unshaken. I am perfectly well aware that the cel paint circa 1932 was water-soluble tempera and not vinyl, and it was tempera that I started with also. As you must know, the paint is pooled or puddled onto the backs of the cels thickly, for smoothness and opacity, and to get it off with a damp cloth would take a lot of time and a lot of clean, damp cloth. I have tried it; it is a mess. It is a mess for just one or two cels. For five or six thousand cels? Just madness.

I do admit, however, that I have only worked with acetate cels, not nitrate.

MB replies: It may be worth remembering here that washing and re-usng cels was commn practice in the early thirties; cels were sometimes washed and re-used so often that traces of the old ink lines showed up on the screen.

While I'm thinking of it, let me recommend Jim Bradrick's excellent blog, which you'll find at this link.

[Posted February 7, 2020]

September 18, 2019:

The Year of the Knees

That's how I'm thinking of 2019, which for me has been dominated by two complete knee replacement surgeries and prolonged recoveries. One unexpected side effect has been that I've felt crummy most of the time, a phenomenon not unique to me, as Jenny Lerew assures me, but highly unpleasant regardless. It has been hard to work up the energy to update this site. What's happening, I have to think, is that repairing the damage from major surgery (which knee replacement most certainly is) absorbs so much of the body's attention that peripheral concerns tend to get swept into the feeling-crummy hole. The end is in sight, but it can't arrive soon enough to suit me.

From Michael Goldberg: You will get better and will look back on 2019 with a touch of nostalgia. The mind has a way of getting beyond pain, and crumbiness! Try to find something every day to enjoy and know that it will get better!

From Benny Zelkowicz: As an animator who has also done a fair bit of writing (unrelated to animation) I know it can be dispiriting or annoying to not know whether our labor is ever being seen, let alone appreciated. So, from this frequent reader of your site, someone who finds your writing informative and fascinating (even, sometimes especially, when I disagree) I want to send you best wishes on your recovery from surgery and hope you are feeling well again soon. (Selfishly, I have been eager to read your thoughts on the passing of Richard Williams…)

MB replies: I wrote about Dick Williams or, more specifically, his book The Animator's Survival Kit, in one of my first posts on this site, in 2003. Long before that, in 1978, I'd written critically for Funnyworld about his feature version of Raggedy Ann and Andy. My one personal encounter with Dick took place a few months after that review appeared, in Los Angeles. Dick was, as I recall, renting space just down the hall from Quartet Films. I was trying to meet as many as possible of the artists that Milt Gray had interviewed for me, for Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, and I was at Quartet to see Mike Lah and George Gordon. When I learned that Dick was in the same building, I naturally wanted to meet him; I didn't know if he'd want to meet me, but he was very gracious and friendly. Milt Gray had interviewed Dick earlier that summer for the cover feature in Funnyworld 19 on the Frazetta-inspired Jovan commercial, and Dick gave me his corrected version of the interview. That was, I think, the extent of our contact, although I recall that we almost crossed paths later in New York. If only Michael Sporn were still with us, he could set me straight on that point right away.

[Posted September 27, 2019]

August 10, 2019:

More on Walt's Goldwater Pin

A dozen years ago, I posted what I thought was an exhaustive consideration of the well-worn story that Walt Disney wore a Barry Goldwater campaign pin when he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon Johnson in 1964. I concluded that, unlikely as it seemed, Walt had indeed worn a Goldwater pin at the cetermony, although maybe not so that it would have been visible to the president.

It wasn't clear, what that pin might have looked like, but now we have a persuasive answer to that question. Dave Mason writes: " I just stumbled onto a photo of what I believe to be the small Goldwater pin that Walt wore on his lapel when he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from LBJ on 9/14/1964. The pin was produced for the Goldwater campaign by the Gerald Sears Co., 377 Fifth Avenue, NYC (same company that produced Nixon's presidential campaign merchandise in 1960 & 1968)."

Dave subsequently wrote with more information about the pin, and a photo of the program for the Medal of Freedom ceremony.

"This little treasure arrived in today's mail… The program came from the White House collection of Sanford Fox… and I found another issue of the pin on eBay. It appears that at least some of the pins were issued with blacking beneath the gold letters to improve the visual contrast. The pin is approx. 7/16" x 7/16"; with no maker's marks that I can distinguish. It seems akin to low-cost disposable campaign materials… not intended for long-term use. It'll be interesting to see if others surface now that I know what to look for.

"I also saw the record of LBJ's White House diary for that day. No sign of [Emile] Kuri [who claimed to be present]! ha… The diary does mention Johnson receiving guests in the Blue Room (as in the photo with Lady Bird you included from the Nat'l Archives; showing the cream colored wallpaper that had been selected by Jackie Kennedy during the earlier renovation) following the ceremony in the East Room (so soon after JFK was lying in state there; I can imagine Lily not really looking forward to that experience). I noticed that the diary mentions several notables weren't able to attend. Would have been interesting to know if Walt was able to greet Edward R. Murrow… then a year after Murrow's cancer diagnosis and removal of his left lung. A poignant moment if there ever was one… Hard to imagine two such prominent members of that esteemed class… gone so soon after this high honor."

From François Monferran: YouTube has a very short video of the 1963 Johnson-giving-Medal-of-Freedom AND one can see that he did not pin anything on anyone's lapel: an attendant ties up a ribbon on the back of the recipient, with the medal hanging from it in front! I do believe that, in 1964, the process was the same … and Indeed, pics show Walt with such a ribbon-medal on him! So, all this Goldwater pin thing seems a little farfetched to me! Walt must have worn the 64-G small pin on his left lapel but President Johnson never pinned any medal on Walt's lapel (left or right) nor did he lean toward Walt; he stayed at the podium, as seen on the 1963 short video, shook hands but I am quite sure he never saw the G pin and Walt never made it obvious! My opinion! Much ado about nothing!

[Posted August 12, 2019]

August 2, 2019:

More Disney Art Brought Out of Hiding

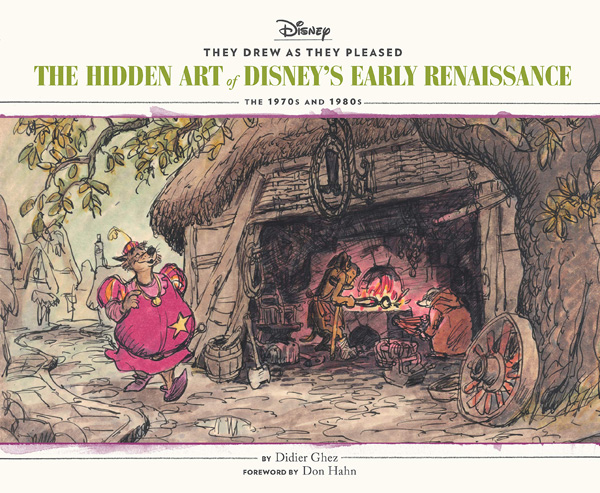

Didier Ghez's series for Chronicle Books under the umbrella title "They Drew as They Pleased" has been the most consistently excellent series of Disney art books of the last few decades, certainly more so than the books published under Disney's own imprint. The reason is not hard to spot, especially when you read Ghez's preface for the newest volume. He has an affection for the drawings reproduced in the books, and an absorbing interest in them, that other writers simply cannot match.

I hold most of the Disney feature cartoons from the seventies and eighties, the period covered by the new book, in low esteem, and applying the term "renaissance" to them (The Hidden Art of Disney's Early Renaissance), as if they were a return to earlier glories, seems strange to me. But, fortunately, the book is not really about second-rate films like Robin Hood and The Rescuers. Instead, it's about the preliminary drawings for those films and the two men who made them, Ken Anderson and Mel Shaw. Their drawings are frequently much more interesting than the films they supposedly inspired. I haven't made a count but I would guess that each man gets more pages than any of the artists in previous volumes. That's good, especially where Shaw is concerned. He has not been overexposed, and his work, as represented in the book, is more individual and even eccentric than Anderson's, which is, for better or worse, more "Disney" than Shaw's. As the drawings reproduced in the book make plain, Anderson set the pattern visually for many latterday Disney features.

There's one more book to come in this series, devoted to artwork from the last few decades—a challenging assignment, I'd say, but I'm sure Didier Ghez is up to it. If you're curious what I wrote about earlier volumes, just do a search on my home page for "Didier Ghez."

The Accessible Walt's People

In addition to the "They Drew as They Pleased" series, Didier Ghez has for many years produced an annual compilation of Disney-related interviews under the umbrella title Walt's People. The books are now published by Theme Park Press. I've authorized the inclusion of many of my own interviews in Walt's People, and you'll find interviews in the twenty-two (so far) volumes by many other toilers in the Disney vineyards. The interviews vary considerably in interest, but it's good to have all of them as a resource.

Taking advantage of that resource has not been easy, though, because the books aren't indexed. Fortunately, that shortcoming has been, if not completely eliminated, greatly reduced. A few days ago, Didier wrote to me and some other friends: "I believe you will all be glad to know that the Walt's People series is now fully searchable online. This is not as perfect as an actual index, but I believe it comes very, very close to a great solution. You can start your search using this link: https://www.dix-project.net/walts_people_search.php Feel free to share the word about this." Done!

July 19,2019:

Toy Story 4

About twenty minutes into this very handsome new Pixar feature, I began to feel the tug of a term that I hadn't thought about much since my college days: "exposition." Here's a short definition, from a dictionary of literary terms that I've owned for decades: "That part of a play in which the audience is given the background information which it needs to know." When writers talk about "exposition," they're typically using the term in a pejorative sense, because flat-footed exposition often takes the place of more inventive storytelling. I think that's the case with Toy Story 4.

How limited are the story possibilities, and thus the characters, in the whole idea of a movie filled with sentient toys, toys whose only goal is—and only can be—to become the property of a child. That premise flaunts its peculiarity in the person, so to speak, of Forky, the hand-made toy assembled, as Forky himself acknowledges, from trash. The Toy Story films have always flirted with existential questions: if countless toys look exactly alike, are they the same toy? If not, how do they differ, and how do those differences arise? It is in Forky that such questions take their strangest shape yet. Unlike the other toys, all of which are factory products, Forky doesn't exist until he is patched together by a child, Bonnie, the little sister of the earlier films' Andy. [Correction: As Jonathan Wilson points out, Bonnie is not Andy's sister] Forky comes alive when Bonnie has finished assembling him, as if he were a sort of Pinocchio and she a juvenile Geppetto, but with no Blue Fairy to expedite matters. Or maybe that's not the best analogy; think instead (but not too hard) of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Inevitably, because it's organized around such an odd and confining premise, Toy Story 4 spends a lot of time trying to gain traction through exposition—that is, by setting up and executing episodes that put the toys to work but are notably lacking in surprise and, especially, energy. Just as well, probably: for one thing, where could the romance of Woody and Bo Peep go, if the film tried to carry it much further?

Comedy doesn't fill the gaps left by the plot. I laughed exactly once during the movie, at the two stuffed-animal carnival prizes, Ducky and Bunny, voiced wonderfully by Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele. They are reminders of how bright and clever the first two Toy Story movies seemed, and of how sobersided the two most recent installments have been by comparison. Maybe having fun with all those toys—and making fun of the very idea of walking, talking toys—has come to seem too much like a repudiation of that great Disney shibboleth, "sincerity."

From Jonathan Wilson: You made an error in one of your paragraphs, Michael. Bonnie is not related to Andy (their mothers are friends, however).

From Donald Benson: It's not just exposition, but what is being exposited. Yes, the Toy Story universe becomes more detailed and complicated -- the real trouble is when that complexity moves from background to foreground. This is now mandatory with franchises: Even James Bond turned from freestanding romps into a continuity, with Daniel Craig accumulating history and emotional baggage from film to film. And my niece-in-law fretted what other Marvel films she had to see before she could understand the latest Spider-Man. Pity the screenwriter signed to a current franchise, having to deal with time-travel, armageddon events and what have you from other product.

Toy Story was about Woody losing his place and Buzz learning he wasn't a hero. Basic, character-driven story. They could fudge the metaphysics because it wasn't about the metaphysics.

Toy Story 2 was largely a metaphor, the choice between sterile security and a risky life of purpose for as long as it lasts (and it's admitted it's not forever). Again, the important story didn't hinge on how toys inherited their personalities from a TV show.

Toy Story 3 had less of a core. It was slick, funny, and mainly an excuse to get the band together. Ironically it was like the first sequel to Back to the Future, which mostly just riffed on what was fresh in the first film while setting up the next sequel. There were a few forcing-the-question moments, such as the toys complimenting each other's "performances" after playtime. Do they have some agency over how Bonnie plays with them?

Incredibles 2 was intriguing in that the superhero story was actually secondary. It was really about Mr. Incredible having to adapt to being a modern dad. The lavish but misfired Cars 2 tried to reconcile a world made of automotive gags (even the insects were VW beetles) with a complicated, technology-driven conspiracy story. Cars 3 wisely retreated to the metaphor of a car as a professional athlete, which allowed for apt and witty equivalencies and shoved the metaphysics into the background. I have to add that Cars Land at Disneyland / California Adventure is a real pleasure: For all the relentless car jokes it's really the mythology of Route 66 realized as Main Street. One can enjoy the atmosphere with no knowledge of the movies.

Likely the makers of Toy Story 4 were trapped not just by the previous films' success, but by the rules those films improvised to make their stories work -- and a large cast of old characters who had to be featured, for fans and merchandise licensees. The metaphysics ended up front and center -- and as you observe, it forces you to think about such things as Woody and Peep having a sex life, how many parts could fall off Forky before he ceases to be a toy, and whether the creepy ventriloquist dummies are sentient toys or some ungodly other.

The preview trailers teased the return of Bo Peep and suggested the story was about Woody choosing love over being a kid's conscientious toy. That's the end of the film as it stands, but it's almost a throwaway. Maybe there was a much smaller movie at the outset.

[Posted July 26, 2019]

June 15, 2019:

While I Was Away...

Away from this website, that is. Travel has not been part of my life since Phyllis and I returned from a brief trip to Key West late last year. I had knee replacement surgery in early April, the first of two rounds, and that surgery has seriously limited me since then. When people tell you that recovery from knee surgery is long and arduous, they speak the truth, but sometimes there's no satisfactory alternative, unless maybe you can avoid stairs for the rest of your life. Surgery on my other knee is coming in mid-August; I will have spent most of this year nursing my knees. At least I have reason to hope that after I've healed from my surgeries, I'll no longer sound like I'm shelling walnuts whenever I bend down,

Because the site has been quiet for five months, I haven't posted comments on a few events that I wanted to say something about, like the passing of Ron Miller and Dave Smith. I still may write about them. And then there's the Tim Burton Dumbo, which I saw in an otherwise empty theater. Audiences have passed a harsh and eminently fair judgment on that movie, so further comment from me might be superfluous. Or maybe not. I've passed on seeing Aladdin, and Ill be skipping the new Lion King, too.

But I've finally finished editing my interviews with Maurice Noble, and you can read about them below.

Interviews: Four With Maurice Noble

Maurice Noble was one of the most enjoyable of the hundreds of people that Milt Gray and I interviewed during research for my book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. As reflected in the transcripts that follow, the talk just flowed, and I ran out of tape more than once in our interviews. Other people, particularly younger people in Hollywood animation, enjoyed his company as much as I did. Like the Disney artist Joe Grant, he became a sort of totem, not just a highly skilled artist but a source of wisdom.

As with Grant, though, I found my own reservations growing—not about Maurice as a person but about his work, and especially the influence of his thinking on Chuck Jones's work as a director. I explained those reservations at length in Hollywood Cartoons, pp. 540-43, and I think they remain legitimate, as much now as when the book was published in 1999.

But there is much to enjoy in the interviews, regardless of what you think about my arguments. You can find all four Noble interviews at this link.

From Thad Komorowski: Thanks so much for posting those interviews. I'm still digesting them all, but the '76 one with Milt might be my favorite of the bunch, if only because it captures the atmosphere of the time so well: that they created so much wonderful cinematic art and now they were retired or resigned to working on crap, and here were you guys trying to figure out how exactly everything happened with absolutely nothing to go on.

I'm amazed that you didn't include that smoking gun of Noble's admission that Maltese would hide the violence in his boards, half-jokingly, but half-seriously, in your book. And he didn't say it just once! It's at once highly revealing and almost single handedly supports your reservations about Noble's influence on Jones' directorship (one that I mostly share). Well, it's out there now anyway, and I'm grateful.

[Posted July 20, 2019]

From Harry McCracken: This is a belated thank you for the Noble interviews. When you said you were working on transcribing them, I began obsessively checking your site to see if they were up. Once they finally appeared, they did not disappoint.

After interviewing Maurice in 1991, I spent a lot of time in his company. His interests were many, and we spent surprisingly little time talking about animation. So your transcripts were full of discoveries for me.

On the subject of what year he was born: He celebrated his 90th birthday in May 2000, and I was lucky enough to attend the large bash some friends of his threw. A year later, after undergoing major surgery, he was gravely ill and didn’t pull through. So even if he was really born in May 1911, I am glad that he jumped the gun.

[Posted August 2, 2019]

From Vincent Alexander: I'm very late on this, but wanted to let you know I finally read through your incredible series of interviews with Maurice Noble and found them fascinating. So many great insights into Noble's approach as an artist and the process of how the Warner Bros. cartoons were made. Thanks for posting it.

One thing I was curious about that you might have some insight on was Noble's references to Ernie Nordli. He refers to him as a straightforward layout man in the Disney tradition, but the Chuck Jones cartoons where Nordli is credited as a layout man strike me as having extremely bold and stylized backgrounds. His work in Broom-Stick Bunny is a standout in terms of off-kilter design, and even the Road Runner cartoon he worked on, Gee Whiz-z-z-z-z-z-z, has some really unconventional color choices. Was Noble misremembering Nordli's work or was Chuck Jones pushing him outside of his natural style?

MB replies: I think the latter was almost certainly the case, as evidenced by how quickly Jones restored Noble to his unit (and dropped Nordli) when Noble became available again.

[Posted September 17, 2019]

From Thad Komorowski: Rereading the Noble interviews, and saw the mention of The Butter Battle Book, and I liked your surprise at the idea of the combination of Seuss and Bakshi. I didn't think much of the special; like a lot of the late '80s Bakshi TV stuff, it's simply a lot of talented people working under too many budget and time restraints to produce anything truly great. But I'd be upset if this story relayed by the late Chris Reccardi, whom we lost earlier this year, wasn't in print anywhere. As Chris came into the office for his first day of work on Butter Battle Book, he heard a car violently speed out of the studio parking lot and into the distance. When he asked what happened, he was told, "That was TED GEISEL... Ralph just FIRED him!" I just think that's a wonderful Ralph Bakshi story that puts the friction between Chuck and Ted into proper context.

{Posted January 16, 2020]

January 24, 2019:

A Cautionary Tale

I don't much like delving into personal history here; other people, like Mark Evanier, are better at it than I am, and usually have more interesting tales to tell. But I'm making an exception here, mostly because telling what happened to me might be helpful to other people.

I'd been seeing the same barber for seven or eight years, with results that were satifactory to me but not to my wife. Phyllis wanted me to try the stylist who has been cutting my friend Roger's hair for years, with results that Phyllis preferred to my barber's handiwork. I finally agreed to see Roger's man, someone I already knew casually, for a trial trim. When I was in Dusty's chair and he was trimming the hair around my ears, he noticed a black spot behind one ear; I'd never seen it, Phyllis had never seen it, and my barber had never seen it, all because it was extremely difficult to see. It was only because Dusty was so thorough, in my first visit to his chair, that anyone saw it. Dusty urged me to see a dermatologist, but I doubted the need, especially since I haven't had so much as a suntan, much less a burn, for decades, and my skin has suffered less sun damage than most people's; but I made an appointment with a skin doctor whose family I already knew. When the results of a biopsy came back a few days later, they were jarring: that spot was melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer. My doctor quickly scheduled surgery with a specialist. I'm now in my third week since the surgery, which I'm assured got all of the melanoma. If I had shrugged off Dusty's warning, the result could have been fatal; since my own diagnosis, I've learned of other people whose melanomas appeared in the same place, and with terrible results.

So, don't shrug off warnings about the dangers in exposure to the sun, or, for that matter, about what can happen, as in my case, if an apparently harmless mole or spot turns deadly. It pays to check yourself in the mirror occasionally, or to ask your favorite barber or stylist to keep an eye out for anything that looks suspicious. Me, I took several nice bottles to Dusty when I saw him again this week.

And now, back to work on the Maurice Noble interview. I hope to have it up by the end of the month, although that's probably too ambitious.

Oh, Pooh!

When I was writing Hollywood Cartoons and The Animated Man I tried to read (or, more often, re-read) as many as possible of the important literary sources of the Disney cartoons, but somehow I didn't pay much attention to A.A. Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh books. Now I'm remedying that oversight. I've read the first Pooh book, Winnie-the-Pooh, and I'm deep into the second, The House at Pooh Corner. I have a better sense of Milne's strengths than I did before, but I still can't warm to the books. For all their droll cleverness, they still cloy (Dorothy Parker was right). I think that's because almost all the characters, Christopher Robin excepted, are toys, stuffed animals. Other children's books, like Johnny Gruelle's Raggedy Ann titles, are populated by sentient toys, too, but almost no one makes any claims for their literary quality. The Milne books, though, are "classics," and so demand more respect than I can give them. Talking-animal stories are one thing, stuffed-animal stories very much another, as far as I'm concerned. Jeremy Bentham was right: real animals are united with us in their capacity for suffering, and so to accept in talking animals, like those in The Wind in the Willows, emotions and even language resembling our own doesn't require an insuperable leap of the imagination. But a stuffed toy bear? No.

I've been struck, as I've read the Pooh books and returned to books like Lewis Carroll's Alice pair, by how closely the Disney cartoons based on those books stick to the narratives laid out in the books (Wind in the Willows may be the cartoon that resembles its literary source the least). What's missing generally in the cartoons based on English literary sources is not specific incidents but rather an evenness of tone that's hard to imagine duplicated in an American cartoon; this is why cartoons like Alice seem so frantic.

Bill Peckmann recently encouraged me to watch a BBC comedy called The Detectorists, about a couple of doofuses who search with portable metal detectors for ancient coins and the like (but more often come up with relics like Hot Wheels cars). Bill writes about it: "I'm probably the only person that sees this connection, but I feel it has a lot of Barksian humor in it. The two semi-anti heroes, who both have a high level of man-child in them—they are responsible and not responsible at the same time—remind me so much of Donald Duck dealing with everyday life, luckily with the same results, meaning with lots of laughs."

I'm afraid I didn't laugh very much, although I appreciate the concept; and there's something delightful about having as one of the two leads Toby Jones, who played Culverton Smith, an exceptionally evil villain, in one of the BBC's Sherlock Holmes episodes. And what do you know! I see he provided the voice of Owl in Disney's misbegotten live-action/CGI film Christopher Robin.

On the subject of A.A.Milne, one more thing. On page 77 of Funnybooks, I noted that Walt Kelly had invoked Milne's stories as the literary model for Pogo, rather than Joel Chandler Harris's Brer Rabbit stories. This despite the Harris stories' superficial similarity to Pogo, especially in their Southern swamp setting. Reading the Pooh stories now, I've been struck by how strong are the echoes of those stories in Pogo. Christopher Robin, sensible and quiet, is the Pogo figure, supervising a menagerie of sweet-tempered but slow-witted animals. Pogo is, for my money, much the superior creation, but Milne deserves credit for providing Kelly with a sturdy armature for his stories.