"What's New" Archives: Sept-Oct 2018

October 24, 2018:

A Little More About Will Vinton

October 16, 2018:

October 11, 2018:

September 16, 2018:

September 14, 2018:

September 10, 2018:

September 3, 2018:

October 24, 2018:

Bigger and Better Barks

Some time ago, one of my European visitors suggested that I post a larger version of the 1998 photo of Carl Barks in his study that accompanies my essay marking the hundredth anniversary of Barks's birth in 2001. Sorry that I can't identify that visitor, but his name and my correspondence evaporated during my computer crisis earlier this year. Regardless, I've finally posted a much larger version, and to see it, all you need do is go to that essay page and click on the photo; that will call up the larger version. (Or so I hope, unless some new disaster intervenes.) You may even want to read my essay, which is a solid piece of work if I do say so myself.

A Little More About Will Vinton

I remembered, after posting my obituary for Vinton on October 16, that I'd had a sort-of encounter with him, or at least with his studio, a few years before I interviewed him in Portland. Rick Cooper, a former member of Vinton's staff, wrote a piece about Claymation that was published in the last issue of Funnyworld, No. 23, in 1983. I commissioned Cooper's piece, but I had quit as editor of the magazine long before No. 23 was published, having finally reached the breaking point with the young financial whizzes who were supposedly going to make a go of it. I'm not sure if Cooper ever got paid the seventy-five dollars he was supposed to receive for his article; I remember receiving complaints about unpaid bills after I'd walked away from the magazine, but all I could do was make clear that I had severed my connection with it years before. I wonder now, recalling Vinton's coolness in our interview, if he had a disagreeable encounter of his own with my successors at Funnyworld. It would be interesting to know.

| Will Vinton in a publicity photo taken around the time of his Claymation feature The Adventures of Mark Twain (1985). |

October 16, 2018:

Will Vinton

Another day, another lamentable passing, this time (October 4) of the stop-motion impresario who gave us the California raisins and other Claymation characters. The very full New York Times obituary is at this link.

I taped a 90-minute interview with Will Vinton at his Portland, Oregon, studio on August 9, 1988, in my role as a business writer. That interview, which I reduced to thirteen pages of single-space notes before writing my story, became the basis for a feature in the section of Nation's Business magazine we called "Making It." I interviewed hundreds of people for the magazine, and whenever possible I'd slip an animation or comics or Disney person into the mix. That was how I got to interview Bill Melendez and Charles Schulz and Fess Parker and John Kricfalusi—and Will Vinton—on the company's dime.

Most of the interviews I conducted for the magazine were highly enjoyable, the animation/comics interviews especially, even though they required a lot of preparation (the Vinton interview was no exception). The people I interviewed had a good time telling me about their businesses, like proud parents, and so I had a good time, too. The Vinton interview sticks in my memory because it was so different. Vinton seemed cold and suspicious from the start, and he never warmed up, even though he answered my questions fully.

I'm accustomed to encountering occasional hostility from the likes of latterday Disney animators who resent something I've written, but Vinton was a special case, someone whose evident skepticism had no source that I could identify. At the end of the interview, I asked if I might see some of the stop-motion sets and characters, and he very coolly brushed me off, as if I'd asked to see some top-secret installation.

Reviewing my notes now, what I find most engaging is what Vinton told me about the practicalities of clay animation. Here he is, for example, talking about the clay itself, a plasticine material:

Over the years, we've done a lot of improvements to it. We get manufactured clay bodies, and through aging it and through adding certain kinds of waxes to it, melting it and adding additives that make it more elastic, we've been able to improve the quality of the clays we get. But we've also done an exrensive serarch of the various manufacturers. We get some of our clay from Florence, Italy, a particular kind of rather solid clay and very rigid. Gives it a little more strength. And a company in Southern California, in Monrovia, that supplies us with a pretty good clay body. The aging thing has been interesting. We've gotten some poor clays from companies that had really good clays before, and have only through a various circuitous, trial-and-error procedure discovered that it needs to sit around for a year and a half before it has the elasticity necessary. So now we age it and keep a good supply on hand. We've thought at various times of acquiring clay manufacturing companies, just to try and improve the quality of the source, but we have a pretty good relationship with the companies that we work with now, that help us to get some of the colors and the consistencies that we want.

The clay, he said, was essentially the same as the modeling clay used by kids; Will Vinton Productions consumed three or four tons a year.

Vinton was forced out of his company fifteen years after I interviewed him (it's now Laika). it seems a great shame that his career, and his life, couldn't end with a happier last act.

From Donald Benson: I remember reading articles and such that casually referred to all stop-motion animation as "Claymation." Vinton may well have been ticked about his trademarked word being treated as a generic term by the press, of which you were a member. One could imagine Harryhausen and Schneer reacting if "Dynamation" (or "Super-Dynarama") were as casually applied to lower-rent scifi flicks.

Also, were wheels already turning that would lead to his ouster? It's an old story, especially when the arts intersect with commerce: A shoestring operation rises on the sweat and creativity of its founders; it gets big enough to attract serious money; the founders become inconvenient or "unrealistic" while their backers become anxious or flat-out greedy. Disney survived being stripped of Oswald and much of his staff, but barely. The Fleischers were efficiently devoured by Paramount. Creators "for hire", especially in comic books, tended to get locked out until comparatively recent years (and even then, it's iffy). Does Richard Williams still have any ownership of The Cobbler and the Thief or whatever it's titled these days?

[Posted October 24, 2018]

October 11, 2018:

Pooh for the Connoisseur

Phyllis and I spent a couple of weeks in New England last month, mostly in Maine but before that in Boston. We devoted a day to the Museum of Fine Arts, which was just opening a big exhibition called "Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic." The exhibition itself was closed for a few days, open only to members of the museum, and as much as we love the MFA, we weren 't tempted to join; a simple daily admission charge is expensive enough. By way of compensation, sort of, the gift shop was stuffed with Pooh merchandise—Disney-authorized Pooh merchandise, of course, so that we left the museum having had our fill of Pooh without ever setting foot in the exhibition.

The Pooh exhibition (which opened at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London last year and then was seen at the High Museum in Atlanta before traveling to Boston) seems to be part of a larger Disney marketing effort, presumably intended to capitalize on the success of the Paddington Bear movies and restore Pooh's somewhat faded glory, most notably through the very odd movie Christopher Robin. "Odd" seems like too bland a word to describe a movie in which stuffed animals come to life and people respond to this witchcraft not with shock and disbelief but with mild surprise. Maybe "sickly sweet" would fit a little better, and maybe that phrase fits just about everything Pooh-related. I certainly felt that way about the animated Pooh movies, and although it has been a long time since I cracked one of the Milne books, I suspect I would respond to them now just as Dorothy Parker did to the House at Pooh Corner, in The New Yorker back in 1928. It is her review, you may recall, that ends famously with these words: "And it is that word 'hummy,' my darlings, that marks the first place in The House at Pooh Corner at which Tonstant Weader Fwowed up."

That said, the CGI animation of the toys is awfully good, and the voices are spookily identical to the voices in the earlier cartoons. I'm not sure why duplicating Sterling Holloway's voice seemed like a good idea, but here's proof that it can be done.

From Donald Benson: I haven't seen Christopher Robin yet, but the impression is near-clone of Saving Mister Banks, much as Bedknobs and Broomsticks was a near-clone of Mary Poppins (and there may be a bit of Paddington envy at play as well). I'd almost bet money somebody at Disney is now developing a movie about a fictive Jack Kirby. The young Kirby's life would jammed with references to and maybe appearances of the superheroes he'd eventually draw ... which, like Poppins and Pooh, are Disney properties.

Of course, an authorized Walt Disney biopic is almost inevitable. There are two unofficial hagiographies out there already:Walt Before Mickey and As Dreamers Do. The trailers border on parody, with a very young Walt talking about revolutionizing entertainment and even building a park.

The California Adventure park includes a statue of Disney as a young man, pre-success but with Mickey already at his side. Now that we're a generation or two past the avuncular uncle of Sunday nights, I'm guessing that's going to be the new official image: the young underdog with big ideas. Something to offset the fact that now everybody's an underdog next to the Disney empire. Not a new strategy -- look at Wells Fago falling back on its old-west reputation for integrity in the fact of monstrous modern scandals.

[Posted October 15, 2018]

September 16, 2018:

Pod People

As I've mentioned here a time or two; IDW Publishing, the leading reprinter of classic comic strips, recruited me to annotate the reprints of Walt Disney's Treasury of Classic Tales, the Sunday page devoted to adaptations of Disney movies. The plan was for four volumes, which would have carried the reprints to within a year or two of Walt Disney's death, but sales dictated that the series be dropped after three volumes. When the third volume was published last spring, I did a podcast about it with Kurtis Findlay, one of IDW's mainstays. Thanks to my computer crisis and other issues, I never got around to posting a link to the podcast, and now I can't make the link work. But I'll keep trying.

Kurtis is an IDW author, most notably of a book called Chuck Jones: The Dream That Never Was, a collection of Jones's very short-lived comic strip called Clifford, with a lot of supplemental material. The book was published in 2011, and I'd put off reading it because I find latterday Jones, whether on the screen or in print, so limp and dispiriting. Clifford is no exception, but Kurtis's supporting text is excellent, the best account I've ever read of Jones's career after he left Warner Bros. Buy the book for that, and skip the embarrassing comic strips.

And speaking of famous cartoonists and podcasts...Mark Kausler has alerted me to...well, I'll let Mark speak for himself:

I've been enjoying a podcast called "R. Crumb's Record Room" , which has been running on the 'net since 2012! I bought a CD set called "John's Old-Time Radio Show" released by Crumb's friend John Heneghan, who has a little band called the East River String Band. John has a very amusing girlfriend called Eden Brower who appears on the CDs with John and R. The website is Eden & John's East River String Band | Home of East RIver Records. There is more than 50 hours of "R. Crumb's Record Room" on there. I haven't heard of any new Crumb illustrated books since his version of the Old Testament some years ago. Maybe he spends all his time spinning old records now. There's a lot of recent stills and little movies of Crumb on that website, including a photo of Aline and Eden standing side by side. Here's a more direct link to the first podcast of "Record Room": http://www.eastriverstringband.com/radioshow/?paged=8

September 14, 2018:

Picture Books

It has been forty-five years since the publication of Christopher Finch's The Art of Walt Disney, the first "art book" about Disney since the early forties. There was a long dry spell between Robert Feild's original Art of Walt Disney in 1942 and the Finch book, but there has been no such dry spell since the Finch book appeared. Instead, there have been dozens of Disney books intended for adult audiences, some, like Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston's Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life, inviting the same serious attention that the Finch book received. This continuous publishing activity crested, or so I hope, a couple of years ago with the publication by the German art-book publisher Taschen of the gargantuan volume called The Walt Disney Film Archives: The Animated Movies 1921-1968. More than six hundred pages long, more than an inch thick, sixteen inches wide, a foot high—I don't know how much it weighs, but it's heavy. Handling the thing is difficult enough, but actually reading it is even harder. I resisted buying the book—for one thing, I had no idea where I'd shelve it—,and my patience was rewarded this fall when I was able to borrow a copy through interlibrary loan for a couple of weeks. In the meantime, the price on amazon.com has dropped from $200 to $125. I've now read most of the book, and I'm still not interested in buying.

The Walt Disney Film Archives is made up of lavishly illustrated essays about all of the animated (or partly animated, as with Song of the South) Disney films produced during Walt's lifetime; many of the authors are names familiar to anyone who keeps up with the "Disney scholarship" that has the company's imprimatur. A few of the essays have some juice in them, like Didier Ghez's piece on The Reluctant Dragon and Brian Sibley's on The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr.Toad, but the prevailing tone, especially in the pieces written by the book's German editor, Daniel Kothenschulte, is reverential. I spotted very few errors, but, likewise, there's very little sense that the authors have come up with new information or new insights (or, for that matter, that such insights would be welcome). There are lots of names, but none of those people come alive on the page. The familiar story is here in which Walt Disney tells the entire story of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to a spellbound studio audience in 1934; never mind that that's chronlogically impossible, all that matters is the bow to orthodoxy. Similarly with the illustrations; they're well produced, but many of the best ones have been worked to death in earlier Disney books.

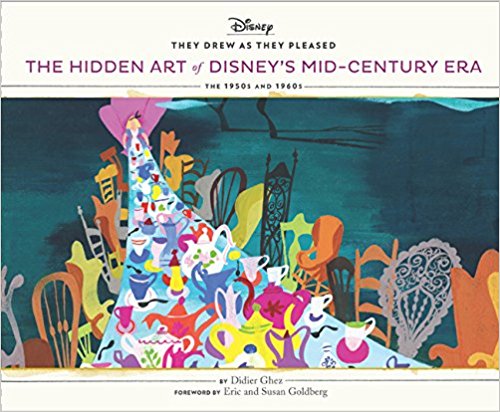

A much better "Disney book" is the fourth volume in Didier Ghez's They Drew as They Pleased series, this one titled "The Hidden Art of Disney's Mid-Century Era." Like the earlier books in the series, the new one offers up the annotated work of a handful of Disney concept artists, in this case artists who were active in the 1950s and 1960s, including John Dunn, Walt Peregoy, and Tom Oreb. The interior of the book, like its title, is not free of awkwardness. The first artist whose work gets a full chapter is Lee Blair, whose Disney credentials were acquired much earlier than those of the other artists in the book, and who didn't work for Disney after the early forties. But Lee couldn't be ignored while his wife, Mary Blair, was being given more pages in the book than anyone else.

A much better "Disney book" is the fourth volume in Didier Ghez's They Drew as They Pleased series, this one titled "The Hidden Art of Disney's Mid-Century Era." Like the earlier books in the series, the new one offers up the annotated work of a handful of Disney concept artists, in this case artists who were active in the 1950s and 1960s, including John Dunn, Walt Peregoy, and Tom Oreb. The interior of the book, like its title, is not free of awkwardness. The first artist whose work gets a full chapter is Lee Blair, whose Disney credentials were acquired much earlier than those of the other artists in the book, and who didn't work for Disney after the early forties. But Lee couldn't be ignored while his wife, Mary Blair, was being given more pages in the book than anyone else.

Fifteen years ago, I wrote about Mary Blair (whom I met when I interviewed her and Lee at their home in Soquel, California, in 1976) in a review of John Canemaker's book The Art and Flair of Mary Blair. I've re-read that review, and I vouch for it, but with an asterisk. I love the jacket illustration for the new Ghez book, a concept painting by Mary Blair for the Mad Tea Party that is, for me, far more attractive than most of her work. The jacket painting (which is also reproduced, more fully, on page 92 of the book itself) depends for its appeal not just on Blair's color but on how that color is organized; this is a drawing with a spine, whereas, for me, a lot of Blair's concept art is soft and mushy. There are other Blair paintitngs, scattered through the Ghez and Taschen books, and before them in John Canemaker's Before the Animation Begins (1996), that succeed in much the same way as the Tea Party painting.

But it is, of course, Blair's color that her admirers most admire, sometimes praising it in the most extravagant terms. Ghez includes as an epigram for the Mary Blair section of his book this quotation from the great animator Marc Davis: "She was the most amazing colorist of all time. I don't think even Matisse could hold a camdle to her." As much as I admire Marc Davis, I have trouble accepting that judgment, maybe because I've seen a lot of Matisse's paintings, in New York and Washington and Moscow, among other places, and I can't recall ever being reminded of Mary Blair. That's not a strike against Mary Blair, only against a comparison that I think may not be very useful.

I wonder sometimes if many of the Disney artists of the "golden age" and, for that matter, many of the artists at all of the Hollywood animation studios in those years, were not handicapped, in ways they may not have fully realized, by their separation from the great museums and schools and galleries on the East Coast (and, once war was not an obstacle, in Europe).. What did it mean to measure yourself or your colleagues against Matisse, or anyone else, if your only measuring sticks were reproductions of variable quality? And if you knew that you wanted to spend a few days marinating yourself in, say, the Matisse paintings at the Museum of Modern Art, how would you do that? How would you find the time to travel to New York? How would you afford to do that? And what about the animation people who were already living and working in New York, and whose work rarely revealed much interest in the fine arts until the migration east of people like John Hubley? There's a book in there someplace (not one I want to write), about the animation traffic to and from each coast, and how it was mirrored in the films.

From Donald Benson: I still have Finch's "The Art of Walt Disney" -- the first one, which I remember coming in its own cardboard box. That, "The Disney Version", a 1963 issue of "National Geographic", and the local library's copy of "The Art of Animation" (the one focused on "Sleeping Beauty") were pretty much it for serious Disney reading in my early teens.

It's hard to overstate youthful excitement over these and other cinema books back in the day, when much of the B&W stuff we simple fans craved was ghettoized on fuzzy UHF channels -- if shown at all. Many books, from coffee table extravaganzas to those bare bones "Films of" books (stills connected by thinnish blurbs), were frankly cheap substitutes for actually being able to see the films. The titles cited were valued for going beyond recapping films. Whether PR fluff or growly criticism, they remain interesting even when the films in question are sitting on DVD nearby.

[Posted September 15, 2018]

September 10, 2018:

Hames Ware

I met Hames Ware, who died on September 5, about fifty years ago. I no longer recall how Hames and I first connected, but our shared interest in old comic books was undoubtedly what brought us together. Over the years, and especially after Phyllis and I moved back to Little Rock from the Washington D.C. area in 2003, Hames and I connected time and again, most recently by meeting every few months for lunch with our friend E.W. Swan, a computer animator, at a restaurant called Burge's. We'd talk politics, mostly, or at least Hames and I did, while E. W., who is considerably younger, listened politely. Then we adjourned to E.W.'s house or mine, to watch old (mostly) cartoons.

if I needed help in identifying the anonymous artists for the Dell comic books of the 1940s and '50s, Hames was the man to call, but his expertise extended beyond comic books: He was an authority on cartoon voices, and one of the pleasures of watching an old Looney Tune with him was sharing his delight in identifying voices that were often obscure, to say the least. Hames did a lot of voiceover work himself but gave up most of it long before he died; I remember that he expressed scorn for the commercial assignments that he certainly could have had if he'd wanted.

Hames was one of those people who never seemed to be in the best of health, but he was an inveterate walker and patron of public transit, and he seemed to lead a healthful life. I'm sure that's why his death came as such a shock, even though he was 75 and despite the occasional hints that all was not well with him.

However firmly Hames is lodged in the memories of friends like me, his most durable legacy is probably the Who's Who of American Comic Books that he compiled with the late Jerry Bails. Published originally in four paperback volumes, the Who's Who has since migrated online. It's the fruition of Hames's lifelong quest for reliable information about the subjects that mattered most to him. For anyone who cares about American comic books, their creators, and their history, it's an indispensable reference, one that I consult often and that will refresh my many pleasant memories of Hames every time I take it off the shelf or visit it on the Web.

There's a full obituary at this link.

From Mark Kausler: I was very surprised to read on your website that Hames had passed away. The following paragraph is a little note I left on the obituary page you linked to. I hadn't talked to or seen Hames in many years, but I'll never forget his kindness, or his dedication to cartoons and especially the voices in them. Wasn't he working on a book about voice actors with Keith Scott for awhile? I hope that book will be printed some day.

I can’t believe that Hames has gone on to that big stage where the lights never dim and every actor sounds like the Barrymores. Hames was a good friend of mine and Mike Sanger’s, a New Mexico cartoonist. Mike and I worked on a little short in the late 1970s called “The Last Cartoon”, which featured a character called “Ding-A-Ling Dog”. Hames contributed the off-screen voice of a “big boss”. Mike animated the scenes with Hames’s dialog as an old fashioned telephone receiver coming to life and actually chewing on the ears of the hapless agent, a character named A. Ratt. Hames was crystal-clear in voice and made the boss sound like a nasal Charlie Lane. Sadly, we never finished the cartoon, it was too big a morsel to chew, but I still have the pencil test of the scene with Hames’s acting in it. He was a very good voice actor, a comics scholar and a great fan of animated cartoons and the people who gave them voice in the theatrical shorts golden age. Goodbye, old friend, we’ll all miss you.

[Posted October 13, 2018]

September 3, 2018:

Bear Sighting in Grand Rapids

Phyllis and I spent a few days in Michigan last month, including a visit to the wonderful Frederick Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park in Grand Rapids. There, in the part of the park devoted to children, we ran across this suspiciously familiar sculpture. Far enough removed from the Disney version to forestall any legal action by Disney's copyright police, or so I assume, but with Disney one can never be sure, as I know all too well.

From Frank Flood: This sculpture is The Boy and The Bear, by Marshall Fredericks, and it was commissioned in 1954 by the Northland Shopping Mall, one of the first malls in the country. Northland was a few miles from where I grew up, and I remember that sculpture as far back as I remember anything. And I am a few years older than Disney's The Jungle Book. Here is some more information on the work:

http://omeka.svsu.edu/items/show/5055

There are a few The Boy and the Bear's around Michigan. The City of Southfield owns the one that was at Northland. The Meijer Garden has a newer casting.

If Disney's attorneys are successful suing over this sculpture, then they are very, very good.

[Posted September 4, 2018]

MB replies: Victor Gruen's name—he's mentioned in the web page to which Frank Flood links, as the designer of the Northland mall—rang a bell, and sure enough, he's mentioned on page 308 of my Disney biography, The Animated Man. Gruen's 1964 book on city planning, The Heart of Our Cities, was a principal source of ideas when Walt Disney was planning EPCOT. Gruen is probably most famous as the designer of Southdale, in Minnesota, the first completely enclosed shopping mall; it opened in October 1956. Northland, outside Detroit, had opened in 1954.

[Posted September 5, 2018]