"What's New" Archives: Nov-Dec 2018

December 18, 2018:

December 14, 2018:

December 9, 2018:

November 24, 2018:

November 6, 2018:

Interviews: Novros, Hurtz, and Julian

December 18, 2018:

How Did That Happen (No. 2)?

Everyone knows about the National Film Registry, the Library of Congress program that each year identifies twenty-five American movies worth preserving. There's a sprinkling of cartoons in the hundreds of films now on the list, Disney features and the like, but of most interest, to me at least, are the essays posted about some of them. J.B. Kaufman writes about Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Pinocchio, the subjects of two of his books, and Mark Mayerson writes about a George Pal stop-motion cartoon from the early days of World War II, Tulips Shall Grow. The best of the essays, for my money, is Thad Komorowski's on Tex Avery's Magical Maestro. That's the only Avery cartoon in the registry; likewise, there's only one Bob Clampett cartoon, Porky in Wackyland, a questionable choice (not represented by an essay) when masterpieces like Great Piggy Bank Robbery have been left out.

There are, however, three of Chuck Jones's best Warner cartoons on the list: Duck Amuck, One Froggy Evening, and What's Opera, Doc? Rather than commission individual essays about each cartoon, the Library has posted a portmanteau essay written by Chuck Jones's grandson, Craig Kausen. That essay is affectionate but insubstantial, and in one respect an embarrassment. Kausen writes of Duck Amuck: "I always loved this quote by one of his brilliant animators: 'It is one of a handful of American animation masterpieces, and likely the most cerebral of them. Daffy makes the most of his opportunity for a definitive solo tour de force. It is at once a laugh riot and an essay by demonstration on the nature and condition of the animated film and the mechanics of film in general.'—Richard Thompson, Film Comment, 1975."

Do I need to tell you that the Richard Thompson who contributed dozens if not hundreds of articles to Film Comment, very few of them about cartoons, is not the same man as the Dick Thompson who animated for Chuck Jones in the 1950s (and whom I interviewed in 1986)? The real mystery here is why the proprietors of the Film Registry's website, who surely know their Thompsons, let such a gaffe slip by. They did Craig Kausen no favors.

Comments

From Ricardo Cantoral: I'm sorry to see that Chow Hound isn't among the selections from Jones' filmography. Not unlike Bob Clampett's The Henpecked Duck, Chow Hound revealed more than what the director intended. For the most part, Jones maintained a sense of humor when he punished his villains. In Chow Hound however, the punishment is grotesque and sadistic. The helpless dog choking on the excess of his own sins, literally. How chilling it was to see the camera pull back as that sadistic cat delivered that fatal blow. I suppose the punishment was equal to the magnitude of the crime but it's so sickening when you think about it. I do love it when I see the dark side of a great artist. Chow Hound was Jones at his best and I dare say, most fascist.

[Posted January 7, 2019]

December 14, 2018:

How Did That Happen?

I've been working lately on a Maurice Noble interview for this website—a compilation of five interviews, actually, one by Milt Gray from 1977 and four that I conducted myself in the late '80s and early '90s (and that's not counting a brief telephone interview when I was tying up some loose ends for Hollywood Cartoons). Pulling that material into publishable shape is taking a while, especially since Milt's interview exists as a typescript and not as a computer file, so perhaps this is a good time for a trial feature I'm calling "How Did That Happen?" That's an umbrella title for mistakes, in Disney books in particular, that are odd and even baffling but can be explained upon closer examination. Here's my first example, a paragraph from Dave Bossert's Oswald the Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons:

...Walt lacked the funds to travel east, and instead had to rely on Jack Alicoate to transport the film to interested New York distributors. Alicoate was a representative of Lloyd's Film Storage Corporation; he had previously held the Alice's Wonderland print during the Laugh-O-gram bankruptcy proiceedng, and was kind enough to help Walt out.

Alas, wrong on all counts. Bossert has apparently made the mistake of relying on Neal Gabler's highly unreliable Disney biography as his source. On page 78 of that book, Gabler writes of "a well-connected intermediary named Jack Alicoate, who represented Lloyd's Film Storage Corp...." On my page identifying errors in Gabler's book, I say this:

John W. "Jack" Alicoate became secretary and business manager of Film Daily upon leaving the army in 1919; he became president and publisher in 1926, and also assumed the editor's title in 1929. There's no reason to believe he ever had any connection with Lloyd's, or, for that matter, to believe that Lloyd's held Alice's Wonderland for Disney in 1923. ... Film Daily was based in New York, and Walt Disney saw Alicoate when he came to New York in February 1928 to negotiate a new contract with Charles Mintz. Any Disney correspondence with Alicoate has apparently not survived—I didn't see any during my own research, and Gabler doesn't cite any—but Disney said in his 1956 interviews with Pete Martin that a friend at MGM had given him a letter of introduction to Alicoate. The passage on page 78 makes sense only as a placeholder, a far-fetched hypothesis that never should have made it into print.

There's a full account of the Disney-Alicoate connection in Timothy Susanin's excellent book Walt Before Mickey, which is based in part on documents that I provided. Bossert apparently didn't consult that book.

I'm reminded of the well-known Disney blogger who gently chastised me for dwelling on Gabler's errors. " Disneyana fans," he said, "tend to shy away from things they perceive as being negative." And that's why, I suppose, they so often embrace things that are careless and false. Maybe there's a happy medium there someplace, but until it shows itself, I'll keep whacking away at errors, my own (see the errata pages for my books on this site) and other people's.

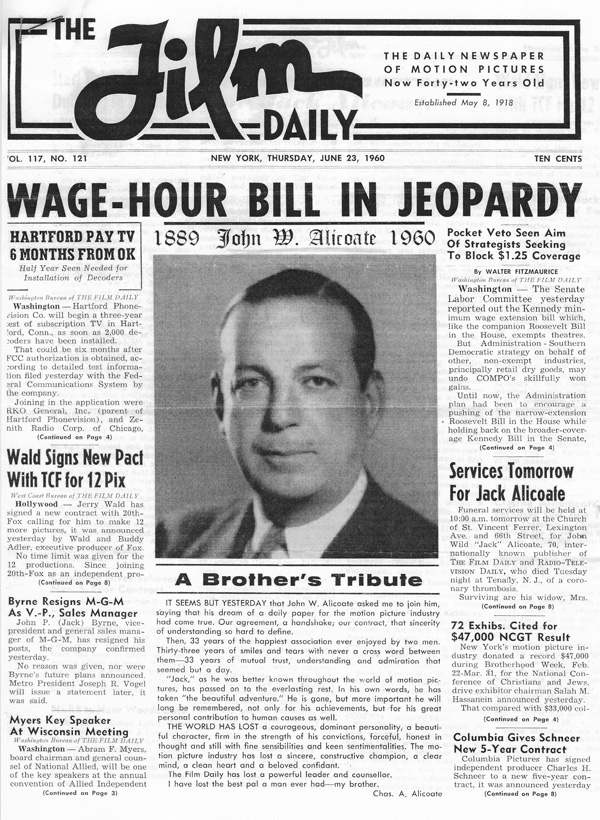

And here, in case you're interested, is the front page of Film Daily for June 23, 1960, announcing Jack Alicoate's death at age 70. Walt Disney was of course still alive then—did he acknowledge Alicoate's death in any fashion? Is there correspondence in the Disney Archives that would show them in touch in later years, after their brief but very friendly encounter in 1928? It would be interesting to know.

From David Nethery: Please keep whacking away at those errors! "Disneyana fans” don’t need any more enabling of their careless embrace of apocryphal stories (and sometimes downright lies). The real story of Walt Disney and his animation studio is always more interesting than the made up stuff anyway.

[Posted January 7, 2019]

From Dana Gabbbard: You quote a Disney blogger in correspondence stating, "Disneyana fans ... tend to shy away from things they perceive as being negative." Not all of us, thank goodness. In the 80s I belonged to The Mouse Club, a very homespun group of Disney fans with an informative newsletter and occasional gatherings. Eventually the founders (elderly proprietors of a collectors shop) retired and an enthusiastic couple took over and mis-managed things into oblivion. When I asked contacts what had happened one told me their personality type was, "they had a wand up their ass," gushy fan types but with no clue about organizational matters. After involvement for years with transit advocacy I can vouch leadership skills are not ubiquitous

[Posted February 5, 2019]

December 9, 2018:

Presidents I Have Seen

Please forgive me for a post with minimal comics/animation content, but I can't resist. The death of President George Bush reminded me of how rare and sometimes odd my own sightings of living presidents have been, even though I worked for sixteen years across Lafayette Square from the White House. A helicopter lifting off the White House lawn, a motorcade up Connecticut Avenue with sirens blaring...that was mostly it. As for actually meeting a president, I did meet Bill Clinton twice, once as governor and once as president, but that was almost too easy, given our shared Arkansas connections.

My close encounter with the elder George Bush took place four years ago in Maine, at the lovely little Episcopal church called St. Ann's by the Sea, just down the road from the Bush family compound in Kennebunkport. Phyllis and I were visiting Maine that fall with fellow Episcopalians from Little Rock, and when it was my turn to choose a destination, on a Sunday, I picked St. Ann's. The service was a few minutes late in starting, and we heard rustlings behind us—"They're coming"—just before several Secret Service (presumably) agents escorted the former president, Barbara Bush, and their daughter past our pew to their seats closer to the altar. George Bush was confined to a wheelchair by then, but instead of parking him in his wheelchair a couple of his escorts wrestled him out of it and into a pew, at one point grasping him by the seat of the pants. Undignified, to say the least, but presumably Bush wanted to be in a pew, no matter what.

The one time I saw Ronald Reagan in the flesh, he was speaking at Constitution Hall, a miserable auditorium, and I was there, for some reason I forget, sitting high up above the podium, surrounded by mostly empty seats. Reagan was funny at first, but then, inevitably, he moved on to boring conservative boilerplate, and I decided to pull out a pen and paper and organize some thoughts for the book I was writing, Hollywood Cartoons. I was sitting near a man in a sport coat with a pipe in his mouth, and as I reached into my suit coat for a pen, I could see him tensing and becoming suddenly alert, relaxing a little only when he could see the pen. Secret Service, of course. I didn't make any sudden movements after that.

My one sighting of Jimmy Carter (apart from an extremely long-distance view of him and Gerald Ford at Carter's inauguration) came at a Crown Books on K Street; Carter was in the store signing one of the many books he has written since leaving office, while a crowd of the curious, including me, grew outside. When Carter emerged, smiling and walking stiffly in a manner that made me think irresistibly of a wind-up doll, the crowd broke into polite applause—except for one man who bellowed "BOOO!" I don't recall that Carter interacted with the crowd, but then, he was not running for anything and those people on the sidewalk weren't going to buy any books, especially the guy who booed him..

As it turned out, seeing the Oval Office was easier than seeing a president. Phyllis's secretary had a cousin in the Secret Service, and one Saturday when President Reagan was out of town, he gave us a tour of the West Wing. The Oval Office itself was roped off, but we could see everything in it. The Oval Office has never been accessible to tourists, of course, but you can see a good replica at the Clinton Presidential Library in Little Rock.

November 24. 2018:

They Came in the Mail...

The fifth volume of Fantagraphics' exemplary Pogo reprints arrived a few weeks ago, days after the latest volume in Fantasgraphics' not quite exemplary but still worthy Carl Barks reprint series. I re-read all of the Barks stories a few years ago, when I was writing my book Funnybooks, so Pogo had to come first. It had been much longer since I read the Pogo dailies and Sundays from 1957-58.

As always with Walt Kelly, the strips in the new book rise and fall in quality, but what's consistent, as I'm sure I've said before, is that there's almost never any sense that Kelly, unlike so many other cartoonists, iis falling back on mechanical solutions to the neverending challenge of filling all those panels. I get tired of Churchy La Femme's manic fear of Friday the Thirteenth, but other schticks that were wearing a little thin in the previous volume have been refreshed here; even the Sunday-page bear is much less tiresome than before. The Sunday page for August 17, 1958, in which an enraged Howland Owl and a matronly bug talk past each other, lifts my spirits every time I think of it. And I have a new appreciation for Kelly's resourcefulness in working around the need to make about 40 percent of the space on his Sunday pages expendable. He had to do that because some papers wanted to knock off the top deck of the Sunday page's three decks of panels so they could sell ads or run another strip, or something; likewise, one panel in the second deck had to be superfluous to meet the requirements of a tabloid layout.

Once you become aware of such expedients, it's hard not to read a Sunday Pogo without thinking of what the page would look like without those disposable panels—but, of course, you want to have the page with those panels in it because they are, after all, Kelly's panels, or, at the very least, panels that Kelly in some sense authored. (I'm sure there are people out there who can infallibly distinguish pure Walt Kelly panels from panels with contributions by George Ward, but that's a skill I do not possess.) I don't know of any syndicated cartoonist, other than Bill Watterson, who was able to defy the newspaper gods and insist that his Sunday pages be presented whole and unmutilated, and Watterson encountered a lot of resentment from philistine newspaper editors who found him downright uppity.

So, now that I've read the new Kelly volume, I'm turning to the work of my other favorite cartoonist, Carl Barks. The stories in the new Donald Duck volume were, like the Pogo strips, originally published in 1957-58, a period when Barks's editors (the spirirtual kin of the newspaper editors who resented what they saw as Watterson's insolence) were starting to squeeze the life out of his stories. So, why am I reading them once again? At this stage of his career Barks was in full command of his medium, the comic-book story, and there's never any doubting his respect for his audience. What's starting to drain away in the stories in the new book, and will diminish increasingly in the stories from the years that followed, is the richness of Donald's personality, his ability, as Barks conceived him, to fill a seemingly boundless number of roles, welll or (more often) poorly. The censored "milkman" story, present in the new book, is like a warning signal: Donald is a sympathetic victim, but he's not really funny, and a Donald Duck who's not funny is pointless. This was the very rare case where Barks's editors may have been right.

When I'm reading something by Barks or Kelly or a few other top-of-the-line cartoonists, like John Stanley and E.C. Segar, I worry a little about my lack of interest in seeking out the work of other comics creators. Then I remember that I've already done that. I read hundreds of stories, thousands of pages, when Martin Williams and I were choosing what to put in A Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics. Years later, when I was writing Funnybooks, I read a lot more.

My original intention with Funnybooks was to write a comprehensive history of American comic books, and so I felt I should read and re-read as many comics as I could. My shelves are still crammed with reprints I bought then, as well as comic books themselves—not just Dell titles like Walt Disney's Comics and Little Lulu, but, for example, Marvel titles from the sixties, when my interest in current comic books was at a peak and I was buying Marvels and a lot of other pubishers' comics. I've since disposed of many of those comic books, but I've saved, among other things, a lot of Marvels credited to Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko and Stan Lee. I enjoyed reading them once—and here's why my comprehensive history came a cropper, and I wound up writing about the Dell line instead—but I don't feel any interest in reading them again. Reading and then re-reading a good comics story is like revisiting a wonderful painting in a museum, or listening to a great piece of music; repetition enhances the experience. I never feel that enhancement when I revisit even the best superhero comics; more likely my pleasure is diminished. But I always return from reading Barks and Kelly with renewed appreciation for their genius.

And maybe, if I live long enough, I'll finally give Herriman's Krazy Kat the sustained attention that it deserves. I've finally got around to reading the first volume of Paul Madonna's remarkable semi-comic-strip All Over Coffee, but I need to read its sequels. I've still got to re-read War and Peace, too.

From Donald Benson: Another Walt Kelly trait: In the early books strips were edited and rearranged to flow like a comic book story; there were often newly drawn panels to smooth things out. While I've seen some adventure strips sliced and shuffled into comic book form over the years, I can't think of another case where reprints of a major humor strip were treated thus (with the mild exception of "Barnaby"). All Kelly's doing, or was there a collaborator / editor somewhere?

And of course there were the illustrated verses and full-on original stories. Pretty sure the swamp critters as Soviet bureaucrats didn't originate as newspaper strips.

After re-reading "I Go Pogo" a few dozen times from childhood on, reading the complete reprint of the first Pogo for President campaign was full of surprises. The newspaper strip followed most of cast out of the swamp (Albert and the gang mistaking an assembly of mice for a political convention). In "I Go Pogo", the raft floated off while Pogo napped and had a whimsical dream about meeting an elephant and a donkey, providing an ending to the book.

[Posted November 24, 2018]

From Kel Crum: Your latest post "They came in the mail" was interesting to me as you mentioned the late Stan Lee and your lack of fascination with his work, as well as other Marvel artists. I feel the same way as I read all the accolades, some of which go as far as to compare him to Mark Twain and other legends.

I've always believed that art is unpredictable and can grow from the the unlikeliest places, but I could never absorb myself too deeply into superhero stories. Defenders will mention that they've been ahead of the curve regarding gender and race issues, with Wonder Woman debuting in 1942 and Black Panther in 1966, and Lee even wrote a story about the world being ruled by woman as a corrective to what men, with their toxic masculinity, have done to it.

There is also the suggestion that superheroes are metaphors for something real. One writer (Sorry. Don't remember who) said that sometimes you have to wear a mask to show your true self.

And yet I always find the intentions more impressive than the final product. Something about them always seems too simple and the characters impossibly stiff. Even when they crack jokes, there's a lack of humor.

The best Donald and Pogo and Calvin & Hobbes comics always felt more human. The artwork shows the little nuances that make human behavior funny. I just don't get that from any single panel of "The Fantastic Four"

[Posted December 9, 2018]

November 6, 2018:

Interviews: Novros, Hurtz, and Julian

Les Novros, Bill Hurtz, and Paul Julian sat for an interview with me at Julian's home in Van Nuys, California, in December 1986. This was a rarity among my interviews because three people (besides me) were talking for the tape recorder. We talked at some length about their work for the Disney and UPA studios, as well as the aborted Finian's Rainbow. Novros and Hurtz both worked for the Disney studio in its "golden age," most notably on Fantasia, and all three men had significant connections with UPA, Julian and Hurtz as members of its staff and Novros in another way; you'll just have to read the interview to see how he described his role. You'll find the interview at this link.

I came away from the interview, and now from editing it, feeling a pang of sympathy for Steve Bosustow, in particular. Artists (and all three of my interviewees qualify easily for that title) can be tough on their bosses! And, for that matter, on some of their colleagues.

I recorded this interview, and many others, as part of my research for my book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, which is still very much in print. I posted the chapter on UPA at this link, on the occasion of the publication of Adam Abraham's history of the studio When Magoo Flew.

From Thad Komorowski: I enjoyed the Novros, Hurtz, and Julian interview greatly. To be honest, I was disappointed... you oversold the Bosustow gossip! So much understated ribbing rather than outright hatred. My guess is that these guys were too sane to be unrealistic about him. Maybe he was just a mannequin that learned some human habits, but whatever he thought of it, no other producer in America would've let Unicorn in the Garden get made. That's got to count for something.

[Posted November 24, 2018]