"What's New" Archives: January 2017

January 13, 2017:

January 4, 2017:

January 13, 2017:

| One of the hundreds of sketches Ty Wong made as the principal styling artist for Bambi. The sketches reproduced on this page and with the interview were taken from photographic slides that Wong provided; he said in a letter that most of the actual drawings were 3 3/4 x 5. "I may have done some larger," he said, "but I did hundreds in 3 3/4 x 5." |

Interviews: Tyrus Wong

I've posted my 1979 interview with Tyrus Wong, the Bambi designer, at this link. Wong's death at the age of 106 has received a remarkable amount of attention in the media, including a front-page obituary and follow-up article in the New York Times and an admiring segment on CBS Sunday Morning. A PBS American Masters episode is to follow this summer. (The two-part Walt Disney show on PBS aired in 2015 under the American Experience label, Walt evidently not qualifying as a "master.") Wong's race—he was Chinese—has figured heavily in the coverage of his death; you'll find the emphasis rather different in my interview with him.

From Kevin Hogan: Thank you so much for posting about Mr. Wong. I think he was long overlooked in the industry, and not just due to his ethnic background.

[Posted January 22, 2017]

Race

The emphasis on racial discrimination in the obituaries for Ty Wong reminded me of a couple of racially tinged incidents when I was proselytizing for one of the Disney cartoons that I most enjoy.

Back in 1978, when I was the guest curator for the Library of Congress' exhibit keyed to Mickey Mouse's fiftieth anniversary, part of my job was to choose clips from Disney cartoons that would run continuously on video monitors. One cartoon I chose to excerpt was Woodland Cafe (1937), whose climactic sequence, the one I chose for the exhibit, is an inspired parody, with insect characters, of the Harlem nightclub called the Cotton Club. This was back in the infancy of videotape, and I had seen that cartoon only once, months before, on a Steenbeck at the library's motion picture division, but it made a strong impression on me. I loved it.

I had forgotten, though, how closely the cartoon's grasshopper jazz musicians resembled black musicians like those in Cab Calloway's band. When the clips arrived from Disney and I saw that sequence again, I was immediately concerned that some visitors to the exhibit might take offense. So I asked several black professionals on the library's staff to take a look and let me know if I should start over. They looked at the clip, and then they looked at me—as if I were nuts. They saw nothing offensive. The clip played at the exhibit for three months, in a city with a very large African American population, and there was not a whisper of complaint.

Fast forward more than thirty years, to 2009, when I showed the complete Woodland Cafe to a class at Washington University, in St. Louis. The first question to me after the screening came from a white woman; I forget the specifics, but the substance was, how could I justify showing a cartoon with such offensive stereotypes? There were some other rustlings of disapproval a couple of days later, when I showed Woodland Cafe to a larger audience in a university auditorium.

My own opinion of the cartoon, that it's wonderful, had not changed over those thirty-plus years, and remains the same today. The cartoon's comedy is sly and exuberant; its distance from anything racially derogatory seems to me unquestionable, especially when it is seen whole. But something had changed, so that what passed without complaint in 1978 had become offensive to some people thirty years later.

Perhaps we're all aware now, more than in 1978, of how stubbornly resistant prejudice is to the cleansing power of what we are pleased to regard as enlightened thought; and so, to let pass any cultural artifact that might seem to enlightened minds to embody discredited notions about race (or gender, or many other things) can become intolerable. Such stringency has not deprived us of Woodland Cafe, at least not yet, but I need hardly mention other cartoons that have been consigned to cinematic purgatory, like the wonderful shorts that are the saving grace of Song of the South, and, perhaps most notoriously, Bob Clampett's Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs.

For me—and of course I'm writing as a white man in his seventies—a critical distinction is whether the use of racial caricatures is contemptuous and mean spirited, as it is, for example, in some of the Walter Lantz Swing Symphonies of the early 1940s and a few Warner cartoons like All This and Rabbit Stew and Angel Puss. But "mean spirited" is the last term I'd apply to Woodland Cafe or Coal Black or the cartoons in Song of the South. And, if I need to say it, even those cartoons that are truly offensive deserve to be seen, so that everyone (adults, anyway) can reach their own conclusions.

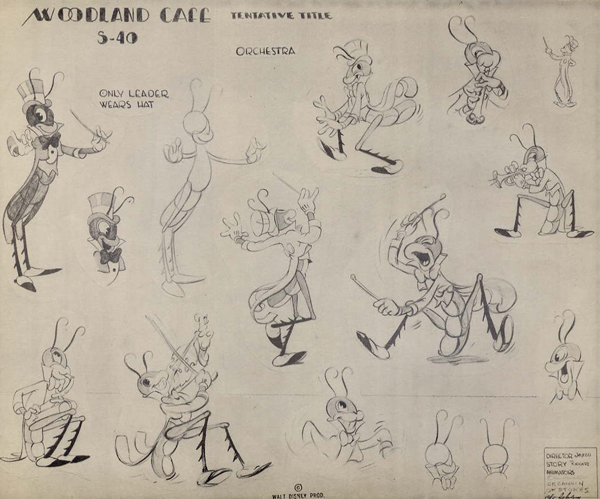

| A model sheet for Woodland Cafe (1937), directed by Wilfred Jackson. Are we to see the grasshopper musicians as having exaggerated lips, as in some black stereotypes, or are those "lips" better regarded as masks of the familiar Felix the Cat kind? I lean toward the latter, but the floor is open. |

From Garry Apgar: Your post on the Woodland Café Silly Symphony brings this comment by Susan Sontag to mind:

In most modern instances, interpretation amounts to the philistine refusal to leave the work of art alone. Real art has the capacity to make us nervous. By reducing the work of art to its content and then interpreting that, one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable, comfortable.

“Against Interpretation,” Evergreen Review, December 1964.

Controlling ideas, making them manageable, via political correctness and other means, is far worse.

From Donald Benson: Speaking as a 60something, my memory of old cartoons, movies and such was that almost every black performer—with the qualified exception of musical artists—was playing a stereotype, the most benign being the loyal servant, self-sacrificing native, or happy slave/retainer. Then there was a period where black Americans barely existed at all, studios and TV producers fearing implied "integration" would cost money in certain markets, while the old stereotypes were poison elsewhere. It was progressive when a black actor played any non-explicitly-black part, such as a bank teller.

To some audiences, particularly those whose media experience of any ethnicity was limited to stereotypes, any but the most neutral portrayal was (and is?) deemed offensive. And the comparative lack of neutral portrayals exacerbated the perception. As you observed, they now questioned whether any exaggerated character could be inoffensive— especially when coming from the bad old days.

The focus is usually on black stereotypes largely because they're usually the most obvious. A modern kid would probably miss that apelike laborers, drunks and cops were specifically Irish caricatures; or that Eddie Cantor was emphatically Jewish. And for some reason, Mexicans, Asians and various rural poor remained fair game long after the worst black stereotypes were unacceptable (in the '60s, Bill Dana could be "José Jimenez" and Mickey Rooney could be Japanese).

Younger audiences might be more willing to laugh, thanks to later performers who pushed out the boundaries on mainstream media. Even "Fat Albert" played a part, with character designs that would have been deemed offensive not so long before. But it's still tricky: David Chappelle abandoned his series because he thought audiences were embracing his comedy the wrong way. And younger audiences are aware that older stuff often accepted and embraced offensive material without irony, which makes them a bit less forgiving (Buffs mock the disclaimers on Disney Treasures and Looney Tunes releases, but it's probably the best way to present uncensored films).

Not quite consecutive thoughts follow...

Lately listening to old Jack Benny radio shows. Eddie Anderson's "Rochester' traffics in some stereotypes, but he stands equal with the rest of the Benny gang in mocking the boss. In the TV version, they were less employer and servant than a vaudeville two-act (both men were short, accenting the effect when taller actors were around). Anderson was never reviled as was Stephen Fetchit, perhaps because of his unique relationship with Benny, and because Anderson was simply more appealing. But even with all Anderson's goodwill, it grates on modern ears to hear imitations of his rasping voice on cartoon characters (with the possible exception of Buzzy Crow). It's usually attached to a blackface gag, replacing the outdated "Mammy" pose.

For jawdroppingly hilarious offensiveness, there's a gloriously bad serial titled "The Lost City". It's packed with screaming black natives, lumbering black zombies, a tribe of white natives who are actually black natives converted by Science, Italians playing Arab slave traders, and short Billy Bletcher -- yes, the voice of Pegleg Pete -- as mad scientist's henchman. A lot of talk about turning intelligent white men into giants, and the hero rejects a proposal from a sizzling Arab femme fatale with what plays as racist contempt. At one point Bletcher confesses he too was converted from a black man; the heroine is repulsed and the seria seems tol think she should be.

[Posted January 20, 2017]

From Garry Apgar: To follow up on my earlier comment on your post titled "Race," and the weightier ideas offered by Donald Benson, we must not, I think, forget that the matter of how race and racial stereotypes were handled in Hollywood, and by Disney in particular, in the 1930s, is extremely complex, and one that remains in many ways both terra incognita and politically charged. Much like issues of gender and anti-Semitism, where high-profile individuals like Meryl Streep brazenly, and loudly, hurl unfounded charges at Walt.

As a cautionary, and leavening, note about Hollywood in general, we might bear in mind what Hitchcock once told Clint Eastwood, when, as Eastwood put it, "I was analyzing a lot of things about his pictures": “Clint, you must remember, it’s only a movie.”

In Disney's case, Woodland Café was only a cartoon. And in most, if not all, instances, the African-American characters in Disney cartoons were spoofs of figures from Hollywood films or elsewhere in popular culture, like the Aunt Jemima doll in Broken Toys.

That said, Walt did of course make a live-action movie with black actors: Song of the South, co-starring James Baskett who received an honorary Academy Award for his role as Uncle Remus—the first Oscar given to a black male actor—which he got in part because Disney lobbied hard on his his behalf. In a review of the film, the very liberal critic Manny Farber, in an article, "Dixie Corn,” published in the New Republic (Dec. 23, 1946), said:

"The honey-sweet Dixie presented in Walt Disney’s first live-action drama, 'Song of the South,' shows plantation life as a paradise for lucky slaves. . . . Despite this hopped-up image of plantation life, “Song of the South” is still the first movie in years in which colored and white mingle throughout, and where both are handled with equal care and attention."

If we are to take cartoons, animation, and Disney seriously, we must be serious (and open-minded) in how we take them seriously.

[Posted January 23, 2017]

January 4, 2017:

Loose Ends in the New Year

The recently concluded year was one of the most dismal I can remember, personally and, especially, politically. This website, a constant source of pleasure to me because of the demands I impose on myself when I'm writing for it, has suffered from neglect. I hope to remedy that in 2017, although whether I succeed will depend on factors beyond my control, in particular my father-in-law's health.

I have a long list of subjects I want to write about, and no time to do them justice, but here, as a stopgap, are a few bits and pieces that might otherwise fall by the wayside.

Trump. No, not that Trump. Ugh. Harvey Kurtzman edited a very short-lived humor magazine of that title in 1956, for Hugh Hefner. Kurtzman's longing for respectability found its fullest expression in Trump, a much slicker publication than those he edited before and after. The contents of both published issues of Trump (and remnants of the third unpublished issue) have now been combined in a single volume by Denis Kitchen, publishing through Dark Horse under his Kitchen Sink imprint.

The book was announced many months ago, and I assume that its publication was delayed at least in part by the regrettable coincidence of its name and that of the Republican nominee. (I spoke briefly with Denis at last summer's Comic-Con, but I didn't think to ask him if that was the reason for the delay.) Anyway: the book is a handsome product, and thanks to Kitchen, most of Kurtzman's best work is now back in print. We still need an anthology of the best of Help!, but the other gaps are few.

As for the contents of the Trump book, I refer you to my review of the complete Humbug (published in 2008 by Fantagraphics). Humbug was the Kurtzman magazine that followed Trump and was generally similar, in the way that a poor relation might resemble a prosperous cousin. There's wonderful stuff in the Trump book, like Ed Fisher's takeoff (in color) on the new "Dinsey" feature Hansel and Gretel, but Kurtzman was at his best, I remain convinced, in the comic-book Mad, especially in those stories that take the measure of the trashy comic-book culture of which Mad was a part. The early Mad was truly satirical (no longing for respectability there), as Trump and Humbug mostly were not, and Mad was for that reason better—funnier and sharper.

Tyrus Wong. The death of Ty Wong, at age 106, was big news over the New Year's weekend. He was, of course, a background stylist for Bambi, and a man of great talent. I interviewed him in 1979, and he lent me slides of a dozen of his concept paintings for Bambi; I had copies made, and that's one of them above. Posting the interview and the slides was on my to-do list for a long time, but those tasks never assumed their proper urgency, I suppose because Ty lived so long. When a man soars past 100, it's hard to escape the feeling that he'll live forever.

His death was a page one story in the New York Times, a story that spilled over onto almost a full page inside. I cannot recall another animation-related person, other than Walt Disney, whose death received comparable attention. (Walt's obituary, like Ty Wong's, was a front-page story in the Times, but, also like Wong's, and more surprising, it started below the fold.) By way of contrast, Chuck Jones's death was marked in the Times only by an Associated Press story, in the obituary section of the paper.

What made Ty Wong's death big news was his race. and the discrimination he suffered as a young Chinese immigrant. The headline on Wong's obituary reads: "'Bambi' Artist Finally Found Acclaim After Enduring Bias." The discrimination was real, of course, and other Asian artists (like the Japanese American Bob Kuwahara) also suffered from it, but Ty Wong had a very long, productive life and enjoyed decades of professional success. His life was not defined by the hostility he encountered as a very young immigrant, and he did not speak of it in our brief interview. Perhaps the disproportion evident in the Times' headline is a price that must be paid sometimes if an exceptional artist like Ty Wong is to receive the attention he deserves.

Because the Wong interview is much shorter than most of my interviews (only nine pages in typescript, compared with as many as a hundred for some other interviews), I may be able to get it scanned and posted faster than usual. Stay tuned.