"What's New" Archives: September 2016

September 24, 2016:

September 20, 2016

September 7, 2016

The Unavailable Carl Barks (in color)

September 1, 2016:

When Was That Darn Mouse Born?

September 24, 2016:

The 'Toons of Summer

I didn't see very many of them, as it turned out. I intended to see Finding Dory, but somehow missed it. I did see The Secret Life of Pets, with a six-year-old boy, a twelve-year-old girl, and four other adults. The little boy loved it, the rest of us hated it. The majority rules. The other animated feature I saw in the warmest months was the Laika feature Kubo and the Two Strings. I was with only one other adult, my wife, and we both loved it. This is a show that I expected to vanish quickly, but it lingered in local theaters for weeks, I'm sure propelled by favorable word of mouth. I've seen Kubo criticized for its overly complicated story, and I can't quarrel with that criticism, but it's emotionally coherent, and that makes all the difference. Phyllis and I both left the theater saying we'd like to see it again, and I'm sure we will.

September 20, 2016:

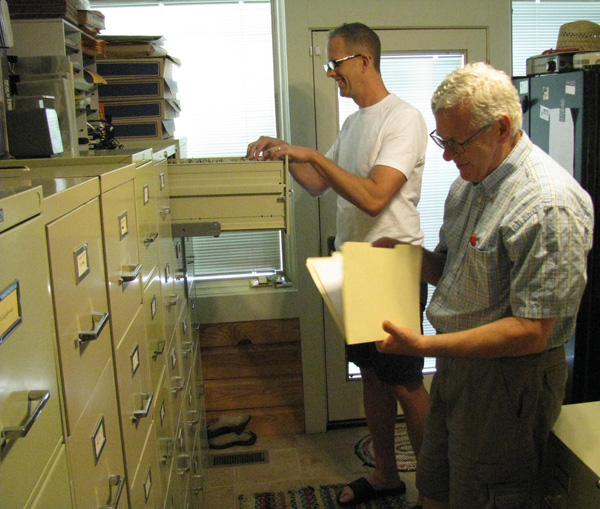

| Pete Docter (seated at the computer) and Don Peri prepare to begin two days of perusing my research files. The gray boxes, filled mostly with comic books, were outside the scope of their research.. |

Visitors to the VBA

That's "VBA" as in "Vast Barrier Archives." But you knew that. The visitors were Pete Docter, Pixar director (Inside Out, Monsters Inc.), and Don Peri, author (Working with Walt). They're collaborating on a book about the Disney cartoon directors of Walt's day, and they asked permission to spend a couple of days reviewing my files related to those people. Since I hold both Pete and Don in high esteem, I was happy to say yes, and they spent what they assure me was a productive weekend, September 17-18, in Little Rock, reviewing my files devoted to the likes of Wilfred Jackson, Ward Kimball, and Dave Hand. They interviewed me, too, with a recorder running—a strange experience that made me freshly aware of how much I asked of all the hundreds of people that Milt Gray and I interviewed decades ago. Given Pete's and Don's thoroughness, the book should be very much worth reading. I'm looking forward to it.

| I've stored most of the material that Pete and Don examined—interview transcripts, correspondence, clippings, documents of various kinds—in filing cabinets like these, in a workroom just off my home office. |

September 7, 2016:

The Unavailable Carl Barks (in color)

The great bulk of Carl Barks's comic-book work was for Disney titles, principally Walt Disney's Comics & Stories, Donald Duck, and Uncle Scrooge. All of that work has been reprinted, some of it multiple times, most recently in the ongoing series by Fantagraphics. Of Barks's non-Disney work, the most important stories are the twenty-six "Barney Bear and Benny Burro" stories that appeared in Our Gang Comics in the mid-1940s; they have been reprinted acceptably by Craig Yoe in The Carl Barks Big Book of Barney Bear.

Ten remaining stories—one each of Andy Panda and Porky Pig, two of "Happy Hound" ( Barks's name for Droopy), three of "Benny the Lonesome Burro" (solo stories before Benny became Barney Bear's sidekick), and three script-only Droopy stories ilustrated by Harvey Eisenberg—make up most of Kim Weston's new book, The Unavailable Carl Barks (in color), which is filled out with restoration notes, alternative versions of a few other stories, and stray pages that have escaped the notice even of the most dedicated Barks admirers.

Let me emphasize how remarkable Kim Weston's achievement is. He located original materials (not artwork, but excellent proofs) for seven of the ten stories. He also came up with source materials for other stories that had been mistreated on the way to the printing press, and they have now been restored to a state that must be closer to Barks's intentions. The "Barney and Benny" restorations from Our Gang Nos. 18 and 21 are especially impressive, given the difficulties they obviously posed. All these stories have been recolored sensitively by Weston and Joseph R. Cowles. Three stories for which no original materials could be found (and almost certainly do not exist), for Andy Panda, Porky Pig, and Droopy, have been reproduced from excellent scans of the comic books in which those stories first appeared. Some of this material was published previously by Cowles in the lamentably discontinued Carl Barks Fan Club Pictorial, but Weston has more than picked up the baton.

It's now possible to own all of Carl Barks's comic-book work, in reproduction that is acceptable and usually much better than that. No admirer of Barks's Disney stories should pass up the chance to explore his handling of other characters by buying Weston's book and the Yoe Barney Bear book. The best Donald Duck stories surpass anything in the two new books, but since those stories are, for my money, the best comic-book stories ever, Barks can be forgiven for producing other stories that are merely excellent—and frequently hilarious.

September 1, 2016:

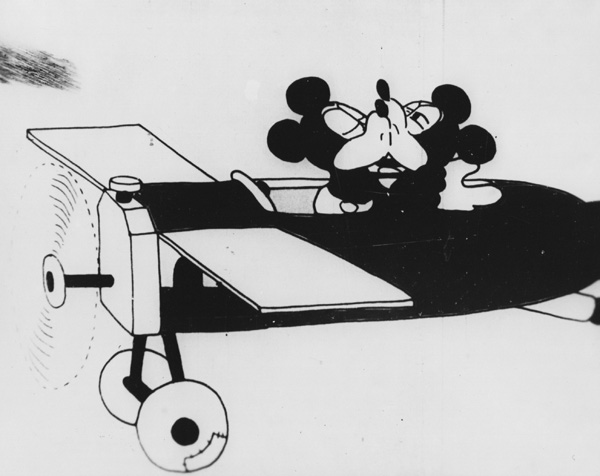

| When Plane Crazy was previewed, as a silent cartoon, on May 15, 1928—the first public exhibition of a Mickey Mouse cartoon—was that Mickey's "birthday"? Or are there other dates with as strong a claim to be the natal day? Walt Disney himself seemed to think so. |

When Was That Darn Mouse Born?

Garry Apgar, author of Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit, writes regarding Mickey’s birth date.

In the introduction to the section in my anthology A Mickey Mouse Reader titled “The Early Years (1928-1931),” I said:

Animation on Steamboat Willie—Walt’s first cartoon planned from scratch as a talkie—was completed by late August 1928. The soundtrack was recorded on September 30th. Which is why, throughout the 1930s, the studio fêted Mickey’s birthday on or about October 1. In the 1970s, the Disney Company began celebrating the event on November 18th, since it was on that date, in 1928, that Willie premiered at the Colony Theatre on Broadway, as part of a lavish bill featuring a live orchestra and the now-forgotten mob movie, Gang War.

In chapter 3 of Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit, I dug deeper into the matter. There I quoted from a letter typed by Walt during his three-month stay in New York, desperately trying to get Steamboat Willie off the ground. He was staying at the Knickerbocker Hotel, at West 45th and Broadway, and the letter, dated September 30, 1928, was addressed to brother Roy “and the gang” back in Hollywood:

Well - we finally recorded the picture this morning……Everything went great…..It worked like clock works….The Orchestra kept synchronization throughout the entire picture….It didn’t get off one beat….. This was a big help to the Effect men and the result was they all hit on the dot. I am sure happy over the whole affair because it proves absolutely that it can be done.

The “Effect men” were the Green Brothers Novelty Orchestra, who counted among their hit records in the 1920s a catchy, syncopated version of “Yes, We Have No Bananas.” When Mickey played the livestock on board Pete’s steamboat like musical instruments, the sounds he produced were furnished by the Green Brothers.

In another letter home, Walt rhetorically asked, “Do you realize what Powers paid the Green Bros. for their work on our picture? (Get ready to faint.).” In a follow-up report, he answered his own question, in all caps: “SIX HUNDRED DOLLARS.” A stupendous sum in those days, and of course, Pat Powers presumably found a way to pass the charges on to the Disneys.

Reiterating what I’d written in the Reader, I concluded: “In Walt’s mind, Steamboat Willie must have been ready to go at that point. Throughout the 1930s, the studio celebrated the anniversary of Mickey Mouse, privately and publicly, on or around September 30th.”

Also in Emblem, I had this to say with respect to Plane Crazy, the first Mickey actually made, although because it was conceived and produced as a silent picture it would not be released as a talkie until March 17, 1929:

Plane Crazy was informally previewed on May 15, 1928, at a theater on Sunset Boulevard—perhaps the West Coast Hollywood Theatre (later renamed the Oriental), at the corner of North Vista Street. Since this was the first public performance of a Mickey Mouse cartoon, May 15th may be considered Mickey’s actual “birthday.” On May 21st, the brothers Disney applied to the United States Patent Office to register “Mickey Mouse” as a trademark, thus unofficially recording his birth.

Nonetheless, as I said in the endnotes in Emblem (p. 302, n. 23):

The studio held a second birthday party for the Mouse on Oct. 4, 1930, at the Ambassador Hotel, Los Angeles (“Ambassador Archive”). Mickey’s fourth birthday was fêted on the studio lawn (Moving Picture World, Oct. 1, 1932, p. 42). The fifth birthday, as noted by Jim Korkis, was celebrated Sept. 30, 1933, “with a Hollywood testimonial party where the speakers included Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Will Rogers.” Time saluted Mickey on his sixth anniversary in its Oct. 8, 1934 issue (“Milestones,” p. 40), and the New York Times (“Screen Notes,” Sept. 28, 1935, p. 13) said that his seventh birthday would be marked on that date at a New York City theater with an “all-Walt Disney program of Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony cartoons.” The London Times, Sept. 25, 1936 (“Mickey Mouse’s Eighth Birthday,” p. 12), reported that the event would be honored (in England at least) on the 28th, and Mickey’s tenth birthday festivities were commented on by the New York Times on Sept. 25, 1938 (“Digest of an Indigestible Week,” p. 5). For information gathered by Korkis, see Korkis [Wade Sampson], “Walt Disney Celebrates Mickey’s Birthday.”

It seems clear to me that if Walt Disney himself celebrated Mickey’s birthday on or shortly after September 30th, that oughta be good enough for me, thee, and all our kith and kin. After all, it was in the wee small hours of the morning on September 30, 1928 that Mickey popped out of the womb, so to speak, of motion picture production and made his first funny sounds.

Walt’s willingness to expend so much time and money on Mickey Mouse, as he would later do to produce Snow White and build Disneyland, reflects his intense devotion to turning out a quality product, whatever the cost. The term “plussing,” a buzzword in recent years in Disney circles, reflects that devotion. It’s a term that speaks so well to Walt’s perfectionism that sometimes (wrongly, I think) it’s applied to his work in animation. However, he seems to have first used the word in conjunction with Disneyland. In a taped interview with Pete Martin in the spring or summer of 1956, from which you quoted in The Animated Man, Disney said:

… The park means a lot to me in that—something that will never be finished. Something that I can keep developing, keep plussing and adding to—it’s alive. It will be a live, breathing thing that will need changes. A picture is a thing that once you wrap it up and turn it over to Technicolor, you’re through. Snow White is a dead issue with me. The last picture I just finished—the one I just wrapped up a few weeks ago—it’s gone, I can’t touch it. There’s things in it I don’t like? I can’t do anything about it. I wanted something live, something that I could, that could grow, something I could keep plussing with ideas, you see? The park is that. Not only—can I add things but even the trees will keep growing. The thing will get more beautiful every year. And as I find what the public likes—and when a picture’s finished and I put it out—I find out what they like, or they don’t like, and I have to apply that to some other thing; I can’t change that picture, so that’s why I wanted that park.

Finally, and slightly off-topic, in Emblem of the American Spirit one of the illustrations (p. 99) reproduces a page from that Oct. 1, 1932, Motion Picture Herald article in which we see a group photo taken at the Hyperion studio. Among the dozens of staff in the photo must have been one “Frenchy” de Trémaudan. Recently I’ve unearthed some fresh biographical information about this relatively obscure Disney artist, more formally known as Gilles de Trémaudan (all too often, in print, the accent is dropped, the two last names run together, and the “de” mistakenly capitalized).

Gilles-Armand-René de Trémaudan was born in Saskatchewan, Canada, March 9, 1909, and died at the Veterans Home of California in Yountville, near Napa, Nov. 24, 1988, which means he must have served the nation in World War Two. He became a naturalized citizen while he was at Disney. Before Walt hired Frenchy in 1930, he attended the Otis Art Institute (circa 1929-1930) and for a while in the early or mid 1930s he was married to an inker he’d met at the studio named Doris Westcott (1912-1995). On June 27, 2011, on MichaelBarrier.com you posted a photograph in which we catch a glimpse of her from behind (Barrier, “Inking at Disney, circa 1931”).

Oh, and one more thing. Thank you for your generous and informed review of my Emblem book and your comment that it is “available now from amazon.com at a bargain price, $26.58.” How true. In fact, there is a used copy currently on offer at Amazon (quality, “very good) for just $16.29. Copies of A Mickey Mouse Reader, published by the University of Mississippi Press, are on sale at Daedalusbooks.com for only $6.98.

Note: the online link for the Ambassador Hotel information cited in the endnote to my book (www.ambassadorarchive.net) is now defunct.

From Ralph Daniel: An interesting article recently regarding Mickey Mouse's birthday. Here's my two cents:

His birthday should be the day he first appeared as part of a paid and publicized performance. That would be November 1928. Previews don't count. A film could be previewed 100 times, but if it never makes it to the Marquee, it's not official. Remember Gone With the Wind was previewed in California, but its only recognized debut is in Atlanta in December 1939.

Otherwise it would be like saying someone's birthday is when they were first identified with ultrasound in the womb. Otherwise it would be like trying to move furniture into a blueprint of a house.

There's an interesting similar kerfuffle here in Georgia. The University of Georgia likes to claim it's the oldest state university in the country by virtue of its chartering in the state legislature. However, the University of North Carolina actually opened first and graduated students first. Although it makes me some enemies, I say that bricks and mortar trump paper, as the chartering could still be on the books but the school not even opened yet.

[Posted September 7, 2016]

From Kevin Hogan: As someone who is an artist myself, I have found that the final "birth" of a work varies. Sometimes a work is pretty much fully formed, with minor adjustments to come, immediately. Other times, the work takes a long time to find it's center. In other words, the work tells you when it is, more or less, complete. The date of inception, as well as the date that the piece ceases to have additional changes, do not necessarily mean as much as when the work finally has definition.

It seems Walt felt Mickey was formed by the 30th of September' that works for me.

[Posted September 22, 2016]