"What's New" Archives: January 2016

January 31, 2016:

January 26, 2016:

January 31, 2016:

Author, Author!

I like to say that this website doesn't generate the volume of comments that others do, but the comments tend to be far more thoughtful and articulate than what you find on other animation- and comics-related sites. Cases in point: when I posted a review of Didier Ghez's They Drew as They Pleased the other day, along with a notice about Garry Apgar's equally outstanding Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit, I heard from both authors. You'll find their full comments by clicking on the link for comments on my January 26 item titled "A Winter of Discontent," but I'll quote from both of them here. First, Didier:

I like to say that this website doesn't generate the volume of comments that others do, but the comments tend to be far more thoughtful and articulate than what you find on other animation- and comics-related sites. Cases in point: when I posted a review of Didier Ghez's They Drew as They Pleased the other day, along with a notice about Garry Apgar's equally outstanding Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit, I heard from both authors. You'll find their full comments by clicking on the link for comments on my January 26 item titled "A Winter of Discontent," but I'll quote from both of them here. First, Didier:

To be honest, I never thought of the drawings featured as masterpieces in themselves, the same way I never perceive single animation drawings as masterpieces. What really fascinates me is the behind-the-scenes of the creative process. Which is why I wanted to fill the book with large amounts of never-seen-before drawings. Each drawing, in itself, might not be a masterpiece, but the drawings taken as a whole give an idea of the richness of the options that the concept artists explored (and often discarded). This is especially true of Horvath and Hurter. When it comes to Tenggren, of course, some of his drawings are masterpieces in themselves. As to Bianca Majolie: I was able to uncover so little artwork that I really cannot tell. The chapter about her, as you certainly noticed, is more a justification to be able to write a whole chapter about women in the Story Department at Disney in the '30s (a story that will be completed in Volume 2) than anything else.

You say "Horvath's drawings, and his personal story, do not in themselves take us very far toward understanding why the cartoons turned out so well." You are absolutely correct, of course. The intent of They Drew As They Pleased was not to explain how Disney cartoons became the masterpieces that they are. This has already been done in the past and never better than in your own Hollywood Cartoons. With They Drew As They Pleased, I attempted to do three things:

- Give a sense of how rich the pre-production creative process was.

- Treat some of the men and women who worked on those animated cartoons and features as individual artists and not just as shadows hidden behind Walt.

- Reveal some of the drawings that history books have been discussing for years but that we had never seen.

I hope I succeeded.

As, of course, he did. For his part, Garry Apgar wrote about my reference to Martin Provensen's description of the Disney studio in the '30s as a "drawing factory."

In the conclusion of Emblem I quote Ray Bradbury, who called WED Enterprises Walt's "Idea Factory." In an earlier chapter, I link Andy Warhol's nickname for his studio operations, "The Factory," to the informal appellation of the Disney operation, the "Mouse Factory." Amusing wordplay, to be sure, involving the parallel, coincidental use of the term factory. But, I think, there's more to it than that.

Walt referred to the Disney studio as a "plant." The industrialization of entertainment and art for mass consumption in the 20th century, exemplified by Disney, was, most famously—among intellectuals and academics, anyway—addressed by Walter Benjamin in his study The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1933). Richard Schickel, in his often ungenerous volume, The Disney Version (1968) spoke, with grudging approval, of Walt's "appreciation of the possibilities inherent in technological progress."

I'm curious about the "industrial" innovations at the Mouse Factory in the '30s: the ways they fit into the bigger picture of how the Hyperion and Burbank studios functioned and grew during that period, and, by extension, Walt's vision for what he was trying to do. By innovations, I mean things like the invention—or perfection—of storyboarding (and the use of leica reels), model sheets, in-betweening, pencil tests, concept art, rotoscoping, and the institution of an educational and training program for rookie and veteran animators in the form of art classes, live model sessions, and lectures by senior men like Don Graham, Dave Hand, and Bill Tytla and guest speakers like Robert Feild and Leopold Stokowski.

They Drew As They Pleased, and the recently published books by Andreas Deja, Nine Old Men, and Don Hahn, Before Ever After: The Lost Lectures of Walt Disney’s Animation Studio, touch upon key aspects of these matters. But, unless I'm mistaken you're the person who, in your books and in posts and interviews on michaelbarrier.com, has most often and informatively dealt with them.

That said, it would be nice to see someone, some day, focus on the totality of Walt's "industrial" innovations and (to quote you) his "openness to experiment" in an in-depth, sustained, and comprehensive fashion. Properly done, and properly illustrated, that would truly be the Disney book of the year, maybe even of the decade.

That would indeed be an outstanding book, which I hope someone else (certainly not me!) will write some day.

I also heard from another exceptional author, Jenny Lerew, whose comments illuminated for me the process by which "art of" books like The Art of The Good Dinosaur come into being. She's the author of one such book, on Pixar's Brave.

I noticed, when visiting Didier's Disney History blog, that he had gotten double duty out of his review there of Garry Apgar's new book, by posting a five-star review of Emblem on amazon.com. I've posted very few reviews there, preferring to concentrate my efforts on this website, but that has probably been shortsighted of me, especially since I recently encouraged my visitors to post favorable reviews of my own books on amazon.com if they were so inclined. Amazon reviews and tweets and Facebook posts and the like seem to have more to do with awareness of a book than the longer reviews that I like to read, as in the New York Times and New York Review of Books. Athough I'll continue to put my greatest effort into reviews for this site, I'll try to cut more of those reviews down to a size that makes for a good amazon review.

Also, I'm now editing my 1976 Jack Kinney interview, and I hope to post it within the next couple of weeks. I expect you'll agree that this is one of most entertaining interviews I've posted here.

January 26, 2016:

A Winter of Discontent

This has been a dreadful winter, not so much because of the weather—which has been better in Little Rock than in my former home in Virginia, as you know if you've watched the reports on winter storm Jonas—as because of illness and injury. Thanks to my father-in-law's broken hip, Phyllis and I have been living in an atmosphere of perpetual crisis since we returned from England in November. You may have heard or read dire warnings about just how serious a broken hip is in an elderly person (my father-in-law is 91). Those warnings are not exaggerated.

This website has been a casualty mainly of my preoccupation with the continuing family emergency, and secondarily of the long-lived virus or bug or whatever it is that and Phyllis and I have been fighting, in the company of any number of friends and neighbors, since late last year. I have a lengthening list of short and long items that I look forward to posting here, starting with my 1976 interview with Jack Kinney (a followup to the 1973 interview that I've already posted).

This website has been a casualty mainly of my preoccupation with the continuing family emergency, and secondarily of the long-lived virus or bug or whatever it is that and Phyllis and I have been fighting, in the company of any number of friends and neighbors, since late last year. I have a lengthening list of short and long items that I look forward to posting here, starting with my 1976 interview with Jack Kinney (a followup to the 1973 interview that I've already posted).

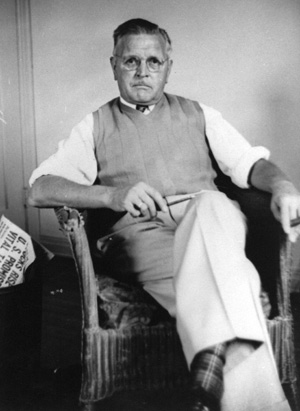

Despite the distractions, I haven't been entirely inactive this month. I've wanted to write more about Didier Ghez's new book, They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney's Golden Age: The 1930s (Chronicle Books)—I posted a brief review, really not much more than a notice, in September—and I squeezed out enough time to write a more substantial piece than I thought might be possible. You can find it at this link. If you're not already aware of the book, it presents a generous sampling of the work of four of Disney's earliest concept artists, beginning with Albert Hurter and continuing through Gustav Tenggren, Ferdinand Horvath, and Bianca Majolie. That's Hurter in the photo at the left.

They Drew as They Pleased, which Didier Ghez expects to be the first in a series of five books covering Disney concept art from the 1930s to the present day, is in many respects a continuation and elaboration of John Canemaker's Before the Animation Begins (1996). Both books belong on the shelves of everyone who takes the great Disney shorts and features seriously.

The Ghez book is just one of a number of new books that command attention from people who care about animation. At the top of the pile is Garry Apgar's Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit (Walt Disney Family Foundation Press), a lavishly illustrated history of the Mouse in his various incarnations (not neglecting his prehistory in the Alice and Oswald cartoons). I was privileged to observe some of the work that Apgar put into assembling this book, and I suspect that only other authors who've labored to get the necessary permissions for an illustrated book can appreciate the extraordinary quality of Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit. Simply tracking down the illustrations for such a book is hard enough; obtaining permission to reproduce them, in an age when the law bends decidedly toward the copyright holder and away from the author, can be immensely frustrating as well as ruinously expensive.

And then, of course, there's the need, when a book is published under the Disney umbrella, to meet what may be, or probably will be, unreasonable demands of one kind or another, even the best books being decidedly subordinate to corporate priorities. (You'll find in Emblem a reference to Wally Wood's infamous "Disneyland Orgy" for The Realist, but not a trace of the drawing itself.) That Apgar's book has survived with so few scars is simply miraculous. I expect to have more, probably much more, to say about the book in the near future.

Giannalberto Bendazzi's name will be familiar to serious animation buffs thanks to his 1994 book Cartoons: One Hundred Years of Cinema Animation (published in the U.S. by Indiana University Press), easily the most comprehensive account of animation's history throughout the world. Until now, that is. It has been superseded—or so I must assume, without having had time to read the new books yet—by three volumes collectively titled Animation: A World History (Focal Press). The first volume may be of the greatest interest to people who, like me, care most about the Hollywood animated cartoons of the 1930s through the 1950s (the first volume cuts off at 1950); or perhaps the later volumes, with their extensive coverage of the relatively unfamiliar animation of Europe, Asia, and Africa, may be of greater interest, since the American cartoons have been the subjects of so much research and writing. It does seem to me that a reader might have more confidence in a book's handling of unfamiliar material if its handling of the familiar is trustworthy, and I'll approach the new books in that spirit. Bendazzi had lots of collaborators on the new books, and that may be a good sign, since the world history of anything is probably too much for one person to handle. More later.

Since I gave Pixar's The Good Dinosaur a tongue-lashing in a review last month, it seems only fair to acknowledge that Chronicle Books has sent me review copies of both The Art of The Good Dinosaur and The Art of Sanjay's Super Team, that being the short that accompanied Good Dinosaur in theaters. Like earlier Pixar/Chronicle "art of " entries, the new books are handsome, and in the case of the feature rather more interesting, I'm sorry to say, than the film itself. But maybe that's because, cynic that I am, I can't help wondering how much of this art was created with the books in mind, rather than the films. It's all too easy to imagine an art director at the publishing house telling someone at Pixar, "We really need better coverage on the dinosaurs' tea party," and someone at Pixar obliging with a handsome new drawing. Not that it would make much difference—would it?

From Jenny Lerew: As always, it's a real, brain-food treat to read your prose-but the very last bit had me grabbing the laptop to respond to this:

...cynic that I am, I can't help wondering how much of this art was created with the books in mind, rather than the films. It's all too easy to imagine an art director at the publishing house telling someone at Pixar, "We really need better coverage on the dinosaurs' tea party," and someone at Pixar obliging with a handsome new drawing.

Believe me, as far as I know nothing like this happens. In my own experience, the film's production designer and the team under him—character designers, art directors, anyone generating artwork—is advised at some point to keep a folder on their hard drive, chosen from the mountains of work they generate for possible inclusion in the "art of" book years down the road.

Meanwhile, they're all living in the moment, busting their chops making revisions, meeting endless deadlines and experiencing all the high-highs and depth-plumbing lows of animation production...no one giving a monkey's about the book until at some late date there's an email in their inbox crying "get your picks for inclusion in the "art of" book together now or forget it!" These artists work their heads off to please themselves and the people who are going to judge what they do. There's absolutely no time mentally, emotionally or physically to do anything with an eye for publication.

By the way, as you've seen these books are almost exclusively devoted to "visdev" or art department work; it's usually only when insisted upon that an animator's preliminary drawings and storyboards are included, and it often seems up to the director if those and various other doodles, gag drawings, photographs, etc. see print at all. Personally (and unsurprisingly) I'm much happier when they do. Pixar and Disney are diligent in that regard, winning my eternal respect. By contrast there's at least one other studio that's taken an exclusionary approach to assembling their books, leaving out virtually anything that's not digital paintings of backgrounds or fully-painted and rendered character lineups. One such volume made no mention that anything like a "story panel" ever existed, much less that there were artists who drew them.

The publisher is concerned with the physical product being assembled and delivered by the deadline, and the editorial content. While the people tasked with laying out the images they're given are extremely skilled and have a great eye, their first and final passes are subject to the approval of the film team. The publisher does not call the artistic shots at all—I doubt they'd dream of doing that. They leave it to the artists working on the film who know it best.

That's my 50 cents on the subject!

MB replies: Jenny knows what she's talking about, not only because she has worked as an artist for years at places like Disney and Pixar, but also because she is the author of perhaps the most substantial of the "art of" books, devoted to Pixar's Brave.

From Didier Ghez: There are actually five more volumes planned in the series [that began with They Drew as They Pleased]. Volume 2 and 3 will cover the 1940s (in fact the late '30s and 1940s). Volume 4 will focus on the 1950s and 1960s, Volume 5 will tackle the 1970s and 1980s and Volume 6 will discuss the 1990s and beyond.

I have just approved the galleys of Volume 2 which will tackle what I call "The Musical Years" and includes chapters about Walt Scott, Kay Nlelsen, Sylvia Holland, Retta Scott, and David Hall; and I am hard at work on Volume 3 which centers on the Character Model Department and will contain chapters about Eduardo Sola Franco (the only non-member of the Character Model Department in that volume), Johnny Walbridge, Campbell Grant, James Bodrero, Jack Miller and Martin Provensen.

To be honest, I never thought of the drawings featured as masterpieces in themselves, the same way I never perceive single animation drawings as masterpieces. What really fascinates me is the beind-the-scenes of the creative process. Which is why I wanted to fill the book with large amounts of never-seen-before drawings. Each drawing, in itself, might not be a masterpiece, but the drawings taken as a whole give an idea of the richness of the options that the concept artists explored (and often discarded). This is especially true of Horvath and Hurter. When it comes to Tenggren, of course, some of his drawings are masterpieces in themselves. As to Bianca Majolie: I was able to uncover so little artwork that I really can not tell. The chapter about her, as you certainly noticed, is more a justification to be able to write a whole chapter about women in the Story Department at Disney in the '30s (a story that will be completed in Volume 2) than anything else.

You say "Horvath's drawings, and his personal story, do not in themselves take us very far toward understanding why the cartoons turned out so well." You are absolutely correct, of course. The intent of They Drew As They Pleased was not to explain how Disney cartoons became the masterpieces that they are. This has already been done in the past and never better than in your own Hollywood Cartoons. With They Drew As They Pleased, I attempted to do three things:

- Give a sense of how rich the pre-production creative process was.

- Treat some of the men and women who worked on those animated cartoons and features as individual artists and not just as shadows hidden behind Walt.

- Reveal some of the drawings that history books have been discussing for years but that we had never seen.

I hope I succeeded.MB replies: I think most readers of They Drew as They Pleased will agree that Didier succeeded very well indeed.

From Garry Apgar: Many thanks for the kind words about my new book Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit, and for squeezing out enough time, as you put it, under trying personal circumstances, to post them.

In your review of Didier Ghez's They Drew As They Pleased, you quote Martin Provensen who called the Disney studio in the '30s a "drawing factory." You also remark that Disney's employment of a "troublemaker" like Ferdinand Horváth was "testimony to Walt’s openness to experiment in the 1930s."

These comments resonate with me in several ways.

In the conclusion of Emblem I quote Ray Bradbury, who called WED Enterprises Walt's "Idea Factory." In an earlier chapter, I link Andy Warhol's nickname for his studio operations, "The Factory," to the informal appellation of the Disney operation, the "Mouse Factory." Amusing wordplay, to be sure, involving the parallel, coincidental use of the term factory. But, I think, there's more to it than that.

Walt referred to the Disney studio as a "plant." The industrialization of entertainment and art for mass consumption in the 20th century, exemplified by Disney, was, most famously—among intellectuals and academics, anyway—addressed by Walter Benjamin in his study The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1933). Richard Schickel, in his often ungenerous volume, The Disney Version (1968) spoke, with grudging approval, of Walt's "appreciation of the possibilities inherent in technological progress."

I'm curious about the "industrial" innovations at the Mouse Factory in the '30s: the ways they fit into the bigger picture of how the Hyperion and Burbank studios functioned and grew during that period, and, by extension, Walt's vision for what he was trying to do. By innovations, I mean things like the invention—or perfection—of storyboarding (and the use of leica reels), model sheets, in-betweening, pencil tests, concept art, rotoscoping, and the institution of an educational and training program for rookie and veteran animators in the form of art classes, live model sessions, and lectures by senior men like Don Graham, Dave Hand, and Bill Tytla and guest speakers like Robert Feild and Leopold Stokowski.

They Drew As They Pleased, and the recently published books by Andreas Deja, Nine Old Men, and Don Hahn, Before Ever After: The Lost Lectures of Walt Disney’s Animation Studio, touch upon key aspects of these matters. But, unless I'm mistaken you're the person who, in your books and in posts and interviews on MichaelBarrier.com, has most often and informatively dealt with them.

That said, it would be nice to see someone, some day, focus on the totality of Walt's "industrial" innovations and (to quote you) his "openness to experiment" in an in-depth, sustained, and comprehensive fashion. Properly done, and properly illustrated, that would truly be the Disney book of the year, maybe even of the decade.

[Posted January 31, 2016]