"What's New" Archives: April 2016

April 7, 2016:

When We Celebrated Mickey's Fiftieth

April 6, 2016:

April 7, 2016:

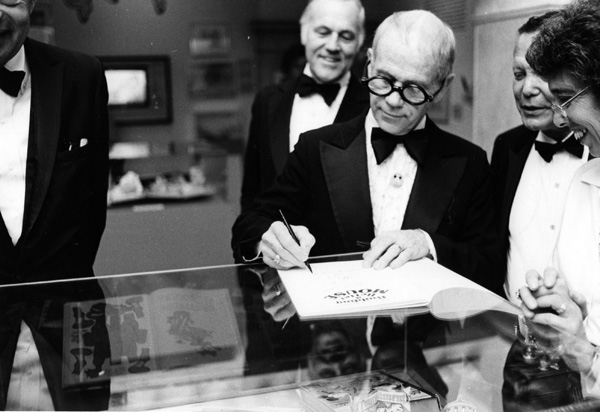

| Ward Kimball, the only Disney animator present, signed copies of the catalog for the "Building a Better Mouse" exhibition at the Library of Congress for guests at the black-tie banquet on November 20, 1978. The exhibition opened to the public the next day. Yes, I still have my autographed copy of the catalog. |

When We Celebrated Mickey's Fiftieth

We are barely more than two years away from the ninetieth anniversary of the premiere of Steamboat Willie at the Colony Theatre in New York City—Mickey Mouse's ninetieth birthday, that is, although I doubt that the Walt Disney Company will make a big deal of it. After all, ninety is pretty darned old. Paying too much attention to Mickey's birthday might even prompt some rude questions about whether there is any justification for extending the copyright term for Steamboat Willie yet again, and, still more to the point, just how it is that extending an existing copyright term stimulates the creativity of people who are long dead. Would Walt have made Steamboat Willie or a much more ambitious and riskier film like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs if the copyright term at the time was only twenty-eight years (fifty-six years with a renewal)? Wait—that's exactly what he did. Next question.I've been put in mind of Mickey's impending anniversary by the recent publication of Garry Apgar's splendid tribute, Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit, a book about which I hope to say considerably more later this spring. That book has also reminded me of the high-decibel celebration that accompanied Mickey's fiftieth anniversary, in November 1978. I played a minor role in that celebration, as the curator of an exhibition at the Library of Congress, titled Building a Better Mouse: Fifty Years of Animation. (The title I proposed originally was Building a Better Mouse: Fifty Years of Disney Animation, which was exactly what the exhibit was about. As best I can recall, the "Disney" was scrapped because one or more people in authority thought it sounded too commercial, or something.) The exhibition, which combined video, items from the Disney Archives, and books from the Library of Congress' collection, opened on November 21, 1978. It was preceded the evening before by a black-tie banquet in the Library's Great Hall; the photos here were taken on that occasion.

The exhibition was so popular that its run was extended by a month. But the Library of Congress is a rather curious institution, a cross-breeding of government and academia, and having curated a very popular exhibition about Walt Disney did me no good at all with many people there, notably at the Library's high-toned Swann Foundation for Cartoon and Caricature Studies. At the time, I needed work and, especially, money to help me finish the book that became Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, but there was none of either to be found at the Library. I don't recall, if I ever knew, just how the Library came to put up a Disney exhibition in the first place, but it does seem curious in retrospect.

| Daniel Boorstin, the Librarian of Congress, spoke at the black-tie banquet in the Library's Great Hall. I'm the dark-haired and bearded man at the table at the lower right. This was the Monday before Thanksgiving, so members of Congress were scarce, but Clare Boothe Luce was there. I didn't meet her, but I did meet Lillian Disney Truyens, for the one and only time. |

| Daniel Boorstin, the Librarian of Congress, with the birthday boy at the banquet. |

| A glimpse of the Pinocchio and Fantasia sections of the exhibition. |

From William Coates: You have mentioned this exhibit on your site a few times. I was curious about how you curated it and what that overall experience was like. What did the exhibit exactly consist of? How closely did you work with the Disney company and the archive? Did the exhibit mostly consist of sketches, cels, Joe Grant's character models, and concept art, or did you include clips from the films as well?

MB replies: Curating involved choosing the items to be exhibited, some from the Disney Archives and some from the Library of Congress' own collections, writing the catalogue essay and the descriptions of each section of the exhibit, and choosing the film clips (there were eight video monitors, as best I recall). I flew to Burbank for several days early in work on the exhibition and reviewed a lot of candidates for display with Dave Smith, the Disney archivist. In the photo just above, you can see a couple of the video monitors and one of the Library's books, in addition to framed Disney artwork.[Posted April 29, 2016]

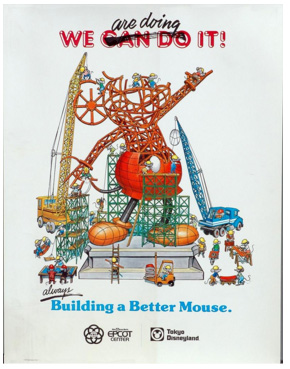

From Garry Apgar: It's purely coincidental ... but Howard Lowery recently auctioned off an in-house Disney poster (above) built around the image that graced the cover of the catalogue for your 1978 exhibition at the Library of Congress marking Mickey Mouse's 50th anniversary. Do you know who did the art work? The execution is so-so, but the design idea behind it was inspired. (Which is one reason why I included a photo of the cover of the catalogue in my own book, Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit!)

MB replies: The cover was designed by an outside firm, I believe, rather than by anyone on the Library's staff. Unfortunately, the file that may hold the answer to that question is stored in my attic—not inaccessibly, but inconveniently. Regardless, I'll try to take a look at it the next time I'm up there.

[Posted April 30, 2016]

April 6, 2016:

Zootopia

As a senior citizen and a former business writer, I tend to be more interested these days in the Walt Disney Company as a very large and very active corporation than as the source of anything of artistic interest. When Tom Staggs dropped out of the running to succeed Robert Iger as Disney's CEO, my first thought was of Iger's own strategy, which has been based above all on acquisitions: Marvel, Star Wars, Pixar. Staggs, I thought, must have figured out that there was nothing left for Disney to buy, and so his own performance as CEO would inevitably suffer compared with Iger's.

Most of Disney's homegrown products, like Frozen, have been conceived in the same intensely commercial spirit as the acquisitions, as "franchises" that can generate not just sequels but many other sources of earnings. I assume such thinking was not absent during work on Zootopia, the most recent Disney animated feature, but here, for once, it's not controlling, and so Zootopia is, for me, the most purely enjoyable Disney feature in many years.

The movie is endlessly clever and inventive in exploiting its basic conceit, that mammals have somehow evolved to the point that carnivores and herbivores live together peaceably (and wear clothes) in what might be called a human city, if there were any trace of humans in it. There are plenty of echoes of human society, in the lemming bankers and sloth bureaucrats, but never any sense that the animals are simply stand-ins. As Walt Kelly once said, a cartoonist "can do more with animals"; they lend themselves to vigorous comedy better than human characters do. The feeling I got from Zootopia was that the people who made it understood what a gift they had in their cast of animal characters, and they relished putting their animals to work.

As always with modern-day Disney cartoons, a few footnotes are in order. The story itself—Judy Hopps, a young female bunny policeman, solves a budding crime wave with the help of Nick Wilde, a fox con man—could have been lifted from the scripts for any number of live-action movies, everything from low-budget crime movies of the 1940s to the Eddie Murphy-Nick Nolte pairing in 48 Hrs. Likewise, the very slow-talking sloths at the DMV quite likely owe their existence to a wonderful old Bob and Ray routine. Such resemblances don't bother me in the least; probably we're supposed to notice them, and why not, since they're not imitations but sly variations on the originals.

Zootopia is a little too long, and there is too much talk. This is another of those Disney movies with multiple directors (Byron Howard and Rich Moore, plus Jared Bush as "co-director"), and hundreds of other credits, and I have to believe that the credit overload has some connection with the movie's excesses; it's almost as if everyone who worked on it had to have a piece they could point to as theirs. But then, Zootopia benefits from a richness of visual detail, in shots of city streets that are full of animals, and surely that detail was introduced into the movie through a process similar to what led to the verbal overload.

If any one thing about Zootopia annoyed me, it was the flashback in which we learn that the fox was mistreated by other young animals and, thus embittered, embarked on a career of petty crime. Simply to say, "Hey, that's what foxes are like" would presumably be unacceptable as species discrimination, even though other animals behave as they might be expected to behave if they wore clothes and talked but were still animals of a particular kind. The sentimentality embodied in that flashback says "John Lasseter" to me, although I have no idea if he was directly responsible for it.

That's a minor quibble, like every other quibble I could raise about Zootopia. It's a very good movie—and a very handsome movie, made with a mastery of CGI animation that I haven't seen in earlier Disney features. The leading characters will surely have long and happy lives as stuffed animals in many children's bedrooms, and they'll deserve the affection bestowed on them.