"What's New" Archives: October 2015

October 30, 2015:

Interviews: Jack Kinney (1973)

October 23, 2015:

October 21, 2015:

James Bodrero...and Alessandro "Vee" Bodrero

October 15, 2015:

October 5, 2015:

October 30, 2015:

| A publicity still for How to Fish (1942), one of the first of Jack Kinney's many Goofy cartoons. |

Interviews: Jack Kinney (1973)

I recorded several interviews with Kinney, the Disney director who is perhaps best known for his Goofy sports cartoons. You can find the first of those interviews, from 1973, at this link.

From Will Coates: Thank you for posting another fantastic interview. Of all the Disney shorts directors in the 1940s, Kinney seemed the most aware of timing and, especially, pacing. The latter seemed awfully lacking in most of the shorts directed during that decade.

I find it interesting that Walt mentions that he didn't "reuse characters." Was that really true? Off the top of my head, I can think of Hannah's No Hunting, where Bambi and his mother briefly appear. And certainly a number of reoccurring characters appeared in propaganda shorts. All the same, this anecdote from Kinney sounds apocryphal.

I look forward to the next interview!

MB replies: Disney did reuse characters, but not extensively—especially after three lackluster sequels to Three Little Pigs—but in this case, I think it's safe to assume that Walt was just trying to dispose of an inconvenient request without offending his friend Sam Goldwyn.

From V. Martin: Thank you for posting your first interview with Jack Kinney. He sure had some very insightful perspectives and interesting anecdotes.

I always found Kinney's cartoons interesting in that they had broad comedy that was unusual for Disney. I've wondered if this was an attempt by Kinney or Walt at competing with the zaniness that came from the Looney Tunes and Tom and Jerry shorts that were rising in popularity at that time.

MB replies: I don't think Walt ever thought in terms of competing with the MGM and Warner cartoons, but certainly members of his staff did. Kinney competed successfully enough that MGM at one point wanted to hire him.

From Don Peri: Great interview with Jack Kinney! Not only have you and Milt elicited some valuable information about Jack’s career and his thinking as a director of Disney shorts, but you have captured his lively personality and colorful language. In addition to his autobiography, this is as close as we will ever come to experiencing Jack’s personality. Thanks for posting this interview!

[Posted November 2, 2015]

From Thad Komorowski: Many thanks for posting the first Kinney interview, and I of course look forward to future installments.

It never hit me, until stated so bluntly in your introduction, how far Kinney fell after the glory days of Disney's. I'm not sure what role Kinney could've played in the organization after the plug was pulled on the shorts, but it kind of stinks one couldn't be found for him after years of consistently funny work.

[Posted November 3, 2015]

From Will Coates: After reading the Kinney interview, I reread the two Jackson interviews. I have been trying to get a sense as to how animation direction worked in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s—basically, the Golden Age of Animation. I'm doing research on Chuck Jones's career and reading these interviews is a way for me to get some context on how direction worked in animation. In most of the interviews that Jones gave that I have encountered, he ends up saying very little about his process for directing—even in your 1969 interview (which is so far the best interview I have encountered on Jones). Rather, Jones and his interviewers pontificate on the meaning of his films. I've gotten far more value out of interviews with the people who worked for him, your interviews with Phil Monroe and John McGrew being two examples. I hope you have more interviews out there with other members of his unit.

So far, the interviews with the other directors have been quite valuable and pleasurable to read. As to how direction works, it seems to vary from studio to studio and from director to director. You had someone like Ham Luske who had more than enough drawing ability to explain what he wanted in a scene. Then you had someone like Kinney who seemed very cinematically inclined, as in he was far more concerned with the pacing of the film than with the animation itself—in some ways similar to Tash. Kinney reminds me of Buster Keaton's method for working, since he seems to emphasize gags and timing over story. Finally, you have someone like Jackson, who would explain his motives to his animators rather than attempt to draw them. Yet, as you and Gray point out, he seemed to be the most capable of all of the Disney directors. Certainly that was the case, as far as the Silly Symphonies go.

With the Disney directors—and certainly with Jackson—the emphasis was on the animators. As is mentioned in the 1973 interview with Jackson, Walt was constantly shifting his animators around. There seemed to be no one unit and, as Jackson himself admits, the concept of director at the Disney Studio seemed nebulous at best. But then you have someone like Jones who seemed to exercise great control over his animators, explicitly indicating the action on his exposure sheets and doling out his own layouts with written directions if needed. This is why I find the jam sessions such a curiosity, since all of the directors, at least according to McKimson in your interview with him, would gather together with their respective storymen and give input on their respective films. Nevertheless, Jones still maintained control. What I want to find out is when and how he got to that point of control. It certainly occurred somewhere between The Night Watchman and The Dover Boys, but it most certainly did not begin with The Night Watchman. I also want to get a sense of who was in his unit, which is why it was a thrill to see Devon Baxter post the drafts from The Night Watchman.

I guess the point of this rambling email is that I want to see if I am at least going in the right direction. There have been many articles written on Jones, but quite a few of them are concerned with the "film studies" aspects of his work rather than its mechanics. In terms of trying to understand the mechanics behind animation and direction in animation during its Golden Age, your work Hollywood Cartoons and your website have been very helpful, as has the blog of the late Michael Sporn's. What fascinates and frustrates me about Jones is that although he was the most interviewed of the Warner directors—or really any director in animation—he ends up not saying a lot; it's all intellectualistic show and no substance. Most of what ends up on the screen may only be able to be explained from whatever documentary evidence is left—and from what I have been told, much of it resides in the Chuck Jones Center for Creativity—and from what his animators have said.MB replies: Unfortunately, thanks to the ongoing crisis in my family, I don't have time to reply adequately to Will Coates's stimulating comment. I do agree with Will's remarks about Chuck Jones's interviews—they are generally disappointing—but I think that Jones was exercising control from the very beginning, in The Night Watchman and others of his early cartoons, and he was exercising control more comprehensively than he did later. What changed was that he gradually began exercising control for the sake of stronger comedy (as opposed to charm and cuteness) and to take advantage of the strengths of his animators, rather than requiring them to mirror their director.

[Posted December 1, 2015]

From Pete Docter: Once again, a great interview. Kinney seems like such a pleasant guy and I imagine it must've been fun to spend the afternoon with him.

Per Will Coates research on Chuck: I'd love to hear what he discovers. My understanding—which may be flawed, but was echoed by Brad Bird when I spoke with him about this last week—is that Chuck not only did rather detailed timing notes for all his scenes on x-sheets, but also did key poses (most often just one or two for each scene). These poses were done on pegged animation paper and could be used directly in the scenes. At Disney's the directors didn't do much in the way of drawing. Jaxon mentions having produced thumbnails for some scenes he directed early in his career, but that's the exception. Even x-sheets seem to often be open for discussion with the animator at Disney's—though ultimately the timing of the film and even individual shots falls under the director's control, especially on Kinney's shows where he was able to shoot the rough animation for the entire short and adjust any timing before animators finished the shots. This seems like a great way to work, given what Kinney was after.

Anyway, I'd love to hear if anyone has read or seen information contradictory to this.

MB replies: I spoke with Chuck Jones at considerable length about his key poses and his timing and his methods as a director in general, especially in telephone interviews in 1976, and I also interviewed many of Chuck's animators and other crew members. A good bit of what Chuck and his co-workers told me is in my book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age; and, of course, some of it is here, as in my 1969 interview with Chuck for Funnyworld, and my two interviews with Phil Monroe. There's no question but that Chuck provided his animators with very detailed guidance, through the poses he drew in his character layouts as well as through the timing on his exposure sheets.

Here is a little of what I write about Chuck's layout drawings and ex-sheets in Hollywood Cartoons, in this instance on pages 484-85:

He said ... that he did not want his animators to use his layouts unchanged, "working into my layouts, and working from them, like wire between telephone poles. ... I wanted ... to demonstrate what the action should be and what the expression should be." Ken Harris, he said, used the character layouts, "to be sure, but usually the body was in a different position; he would preserve the expression." ...

He tended to speak of providing his animators with many hundreds of layout drawings; he said in 1975, for example, that he gave them a key drawing for every two-thirds of a second of screen time, or one for every sixteen frames of film—an extraordinarily high figure, considering that the Warner cartoons were shot almost entirely on twos and that Jones would thus have been making one layout drawing for roughly every eight cel setups (the drawings traced onto one or more layers of celluloid). Few animators, if confronted with so many drawings, could do much more than inbetweeen them. On another occasion, Jones said that the number of layouts for a six-minute cartoon "probably came out between 250 and 350, sometimes more," a more reasonable ratio of one character layout to every ten to fifteen cel setups. He spoke, too, of holding his animators to strict timing, "by necessity, because I found out if they ... lengthened a hold by two more frames [shooting on twos], they would also lengthen the other end by two frames, and that's four frames, and if it's a twelve-frame hold, the different between twelve and sixteen is enormous." ...

"All of my animators had to obey my exposure sheets," Jones said, "but I soon learned the kinds of persons they were, and I'd give them the kinds of scenes that related to the kinds of persons they were, and I adjusted the action to fit the people." As his collaborators assumed more of the load, Jones's stamp on their work actually became stronger; he may have given his animators fewer drawings than in the early forties, but those drawings were far more dominant. ...

Apparently, no complete sets of Jones's character layouts have survived for any of his cartoons from the late forties and early fifties, or even for short sequences. But many individual layout drawings have survived, and many others were used to make up the model sheets of new characters.

[Posted December 28, 2015]

October 23, 2015:

| A representative page from the 48-page story that fills Zane Grey's Wilderness Trek, Dell Four Color Comic No. 333, 1951. Adapted by Gaylord DuDois, illustrated by Moe Gollub (who hated to letter, thus the unfortunate mechanical lettering in this and other stories). |

Reading Gaylord DuBois

A few weeks ago, I posted an item asking that my visitors consider posting a favorable comment about one or another of my books on amazon.com, if they were so inclined. A number of people responded as I hoped, with substantial comments that showed they'd actually read the books. I particularly enjoyed Harry McCracken's comment about Funnybooks, not just because he liked the book but also because he disagreed with some of what I said in it: "I'm still not entirely clear on why he devoted as much space to a writer named Gaylord DuBois as he did, and I wished for a little more on Paul Murry than the one passing mention he got." I'm happy to have the opportunity, thanks to Harry, to revisit what I've written.

I have no regrets about giving so little attention to Murry, who was, like so many of his "funny animal" peers, a terribly limited cartoonist compared with Carl Barks (whose work Murry scorned). Murry relied on a set of stock poses and expressions, executed with an emphasis that partly concealed how ordinary they were. A direct comparison of the two cartoonists is possible, since Murry illustrated panel-by-panel copies of at least two Barks stories, including a 1960 version of "The Gilded Man" from Donald Duck Four Color No. 422, 1952. The comparison is not flattering to Murry.

It's a little more difficult for me to justify the attention I pay to DuBois—a full defense would require that I quote too much from the pages I devote to him in Funnybooks. For me, tracing DuBois's career was a way to understand what life was like for a comic-book writer in the 1940s, and, more than that, a way to distinguish the Dell line from its competitors. As I write near the start of a chapter I devote to DuBois, his scripts "set the tone for the whole Dell line, which was free of almost everything that was lurid and morbid and generally excessive in competitors' comic books. ... [B]ecause DuBois's scripts were more archetypally 'Dell' than anyone else's—because they established a baseline—they opened the way for other creators who preferred to work in the same vein. There was in the Dell comic books the opportunity to make much better stories than the comic-book industry usually permitted."

That's exactly right, I still think. Since I wrote Funnybooks, I've revisited a number of stories with DuBois scripts, and I've come away with my respect for his work enhanced. I like the stories in Gene Autry Comics that Jesse Marsh illustrated, and I realized when I read one of them recently that it fit perfectly my description of the DuBois stories in which "his characters calmly work through practical problems." And, sure enough, the listing of DuBois's work compiled from his own records shows that he wrote a few Gene Autry stories at just the right time. I like the DuBois scripts illustrated by Moe Gollub, too, such as those for the early issues of Lassie and some of the Zane Grey adaptations. The best of those stories, written and drawn almost seventy years ago, have what is for me an appealing nineteenth-century flavor: calm and ordered, script and drawings speaking together as if in a strong and measured voice. DuBois was, after all, born in 1899, when Queen Victoria was still on the throne.

Another prominent writer for Western Printing's comic books (excluding writer-cartoonists like Barks and John Stanley) was Paul S. Newman, who was twenty-five years DuBois's junior and began writing for Western about ten years after DuBois. Newman is best known, probably, for his scripts for The Lone Ranger and Turok Son of Stone and the Gold Key title Doctor Solar. He was prolific, and like DuBois, he documented his work. We know what Newman wrote; my problem was, when I was writing Funnybooks, that I couldn't identify anything he wrote that I found particularly interesting. I remember disliking The Lone Ranger, both the writing and Tom Gill's drawings, when I was buying all the Dell comics in the 1950s, but surveying the list of Newman's work now, I don't see anything that sticks out, either good or bad. Perhaps it was just that Newman's timing was unfortunate; he came aboard as it was becoming more and more difficult to write really good comic-book stories of the kind Western had been publishing.

I wound up not mentioning Newman at all in Funnybooks, and I didn't mention any number of other writers and artists whose work I don't dislike, exactly, but that I think offers too little to admire (Dan Spiegle comes immediately to mind). No one has challenged me on Newman's omission, or on other points that I thought might provoke discussion. Testimony, perhaps, to the clubbishness that prevails in comic books as in animation, and that weighs against serious efforts to separate the four-color wheat from the four-color chaff. (If Tony Strobl is, as I've read, a great cartoonist, what does that make Carl Barks?) So, thanks again to Harry McCracken for breaking the silence.

From Harry McCracken: I certainly didn't expect you to write more than briefly about Murry, and I don't argue that he was one of the greats. In fact, for much of his career, he seemed to be hacking his work out. But I do like some of the early stories he illustrated, where he seems more engaged by his assignments and his experience in animation is especially visible.

MB replies: I'd probably point also to some of Murry's early work as his best, perhaps singling out his first comic-book stories, "Uncle Remus" in Four Color Comic No. 129, 1946. For those readers not familiar with Murry's history, he was an assistant animator under Fred Moore at the Disney studio in the early forties before becoming a full-time comics artist.

From Michael Morgan: I found the passing referral to Tony Strobl to be very insightful. Being a '50s child, I've long admired the artistry of Al Hubbard, with whom the much admired Strobl shared duties on a personal favorite, "Mary Jane and Sniffles," for nearly ten years. Your Strobl/Barks hypothetical is, I think, also appropriate to Strobl/Hubbard.

MB replies: I'd agree; the Hubbard-illustrated stories have a sweetness and charm that the Strobl-illustrated stories lack. I see in Hubbard's work, especially his stories for the "Peter Wheat" giveaways, an awareness of Walt Kelly's fairy-tale stories.

[Posted October 24, 2015]

From Thad Komorowski: It does seem pointless to devote word space just to slag on a cartoonist, but there is ample evidence that Paul Murry missed his calling. His art for Dick Huemer's Buck O'Rue is generally excellent and I like his cheesecake cartooning quite a bit. It's inescapable he, like so many of his Western colleagues, was resigned to hackwork given the increasingly rigid standards. A shame. His penchant for gangly, deformed humans and buxom girls would've been a perfect fit for Mad.

For what it's worth, I never could get into the Western Mickey Mouse comics—period. Either the cartooning was simply bad (Murry), or the dialogue and exposition too heavy (see "The Ghost of Man-Eater Mountain" that was just reprinted in IDW's Mickey Mouse this month). Or both. I vastly prefer the Mickey Mouse Romano Scarpa provided Italian readers for decades.

And the answer to that is fairly simple... If Tony Strobl is a "great cartoonist," then Carl Barks is an "amazing cartoonist!"

[Posted October 25, 2015]

October 21, 2015:

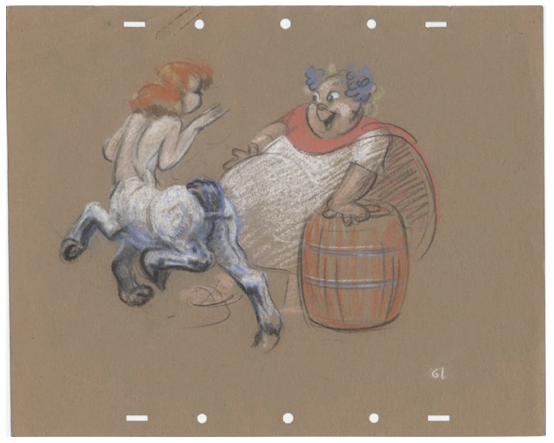

James Bodrero … and Alessandro “Vee” Bodrero

Garry Apgar, editor of A Mickey Mouse Reader and author of the forthcoming Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit, has written this guest post on the Disney artist James Bodrero, the subject of multiple posts here in the last few months. Bodrero was a fascinating character, and as Garry has learned, his brother was a very interesting fellow in his own right.

As a follow-up to your August 6th review, “On the Road with James Bodrero,” your reminder link to Milt Gray’s Q&A with Bodrero from January 1977, and my brief August 25th guest post about two Old West-themed books he illustrated, I’d like to offer some new information about Jim Bodrero and, in particular, an obscure Bodrero sibling likewise employed by Disney.

As you said in your lead-in to Gray’s interview (posted in 2008),

Jim Bodrero differed considerably from most of the other people who worked at the Disney studio when he did (1938-1946). He was older—older than Walt Disney himself—and vastly more sophisticated and socially well connected.

Among his contributions to the production of Disney feature-length cartoons were character sketches and concept drawings like the pastel (above) for the “Pastoral Symphony” segment of Fantasia, auctioned by Howard Lowery in 2013 (hammer price: $1,560.00).

As you noted, too, in your intro to Gray’s Q&A, Cornelius “Corny” Cole, who worked for a while as an in-betweener on Lady and the Tramp, was Bodrero’s nephew by marriage. But Jim Bodrero had another, even closer family tie to Walt’s operation in the person of a younger brother named Alessandro.

An online death notice in the Los Angeles Times (December 18, 2002) states that Alessandro S. (“Vee”) Bodrero was born on May 1, 1909 in France, and died in Malibu on December 5, 2002. Jim, as you learned from his daughter, Lydia Hoy, was born in 1900 in Belgium.The Times notice also had this to say about Alessandro Bodrero:

Beloved husband for 65 years of the late Jean Strachan, who passed away in Oct. 2001, father of Alexa, John and Victoria, grandfather of three and uncle of seven. Vee was a pioneer air pilot in Southern California. He served as a lieutenant colonel in the Marines during WWII. After the war Vee worked as a cameraman in the film and TV industry beginning at Disney Studios in the early days, then Desilu and Paramount, and USO Tours with Bob Hope. Vee will be remembered with much love and affection by his family and friends. He was a uniquely talented individual, a great storyteller and a fine craftsman.

There is a short entry on Alessandro Bodrero on the Internet Movie Database website, although, like the Times obit, it makes no mention of Jim, which—if the two men were related—is odd . . . unless, perhaps, they or their families were estranged.

Another website, Wikitree, does, however, list a sister and two brothers for Jim Bodrero: Lydia, Gian, and Alessandro. In addition, records from Ellis Island indicate that a Catherine Bodrero, age 35, arrived in New York from England on April 11, 1910, aboard the SS Minnewaska with four children in tow: James (age nine), Lydia (eight), Gian Giacomo (three), and Alexander (eleven months). The mother, née Spalding, was an American citizen. She made the voyage having by then, presumably, separated from her spouse. In its March 31, 1939 edition, the Palm Beach Daily News reported that Catherine had divorced her Italian husband, Alessandro Boldero, “some years ago.”

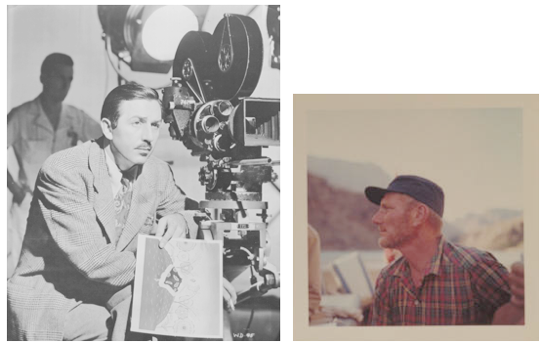

I’ve found just one photograph of Vee Bodrero (apparently also nicknamed “Vitty”). The description of the image reproduced below right, in the collections of the Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif., identifies him as “assistant to Jim Algar in the making of the Disney motion picture 'Ten Who Dared'.” The snapshot, taken by J. Ballard Atherton in June 1959, is among the Papers of Otis R. Marston at the Huntington. Otis “Dock” Marston was a technical advisor on this live-action film produced by Algar, which premiered on October 18, 1960. Ten Who Dared may have been one of Vee Bodrero’s last assignments at Disney.

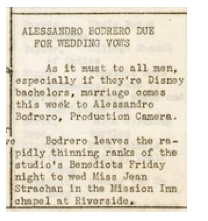

Precisely when Vee’s relationship with Disney ended is unclear, but it began far earlier than indicated by the Times death notice. He was hired on April 13, 1939, six months after brother Jim, who joined the studio on October 3, 1938. Prior to the war, Alessandro worked in the Camera Department (“Production Camera”). That might be him standing in the background of the George Hurrell publicity shot of Walt above left, taken in the early 1940s. Both figures have the same lean physique and the same longish shape and subtle tilt of the head.

Alessandro’s position in “Production Camera” is mentioned in a wedding announcement in the September 8, 1939 issue of the studio’s mimeographed in-house newsletter, The Bulletin (vol. 2, no. 10, p. 1):

Like his brother, Alessandro Bodrero was one of many fascinating people employed by Walt Disney over the years. There must still be much to discover about him.

For instance, the Findagrave website offers no indication regarding where he or his ashes may have been laid to rest. But it does give Vittorio as his middle name—as opposed to the middle initial “S” reported in the Times death notice, in Disney personnel records, and in military records as well—which might explain the origin of the nickname Vee. Findagrave.com, incidentally, also specifies Jim Bodrero’s birthplace in Belgium as Liège.

Regarding Vee’s military rank during World War II, the L.A. Times notice also got that wrong. He was never a Lieutenant Colonel. Nor was his wartime service his first stint in the Marines. According to official records, he first enlisted in the Corps in Los Angeles on January 7, 1935 and underwent recruit training in San Diego. He then served with Service Squadron 2M, Observation Squadron 8M, and Utility Squadron 2M. Presumably, these units were stationed at Camp Kearny in San Diego, future site of Marine Corps Air Station Miramar.

Vee Bodrero was, it seems, discharged soon after December 1938, following a four-year tour of duty. The comment in the Times obit that he “was a pioneer air pilot in Southern California” may reflect an interest in aviation developed during his service at Camp Kearny. It also might indicate a passion for flight that predated and prompted his enlistment in the Marines in the first place.

According to Marine Corps documents, Vee re-enlisted in January 1943 (one year and one month after Pearl Harbor), with the rank of Staff Sergeant, and was sent to Quantico, Virginia, for officer training. The first issue of the in-house wartime studio publication Dispatch from Disney’s (1943) reported that he was stationed at Quantico in the Animation Unit of the Marine Corps Photographic Section. He subsequently served as an intelligence officer in Marine Bombing Squadron 611 (VMB-611), which reached the South West Pacific Theater of Operations in late October 1944 on board the SS Zoella Lykes. He is listed as “Boderero” on the unit’s website, with the rank of 1st Lieutenant.

In January 1946 Alessandro was a member of the Wing Service Squadron 1 in Tsingtao, China, By July 1946, he’d been assigned to the 11th Reserve District in San Diego, where—still a 1st Lieutenant—his active duty came to an end. As recorded in the Register of Retired Commissioned and Warrant Officers, Regular and Reserve, of the United States Navy and Marine Corps (Bureau of Naval Personnel, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1960), upon his retirement from the Marine Corps Reserve in 1959, the rank of Captain was the highest grade he attained during his career.

Ironically, roughly three years after Vee left the “rapidly thinning ranks of the studio’s” bachelor corps and, in 1943, rejoined the ranks of the United States Marine Corps, he found himself almost literally at war with his father and namesake. Alessandro Bodrero the elder—who bore the honorific title of Commendatore—was an army general and high-level diplomat in the service of Hitler’s chief European ally. In the words of historian Luca de Caprariis, Generale Bodrero (1865-1953) had once been “Mussolini’s personal emissary to King Alexander of Yugoslavia and from 1924 to 1928 Minister in Belgrade, was one of the few hard-liners” in the Italian diplomatic service. In 1939 the Palm Beach Daily News reported that Bodrero held “an important position in Ethiopia,” which Italy had occupied in 1936.

The Camera Department at Disney spawned at least one other Marine Corps officer during the war. On September 22, 1942, Walt signed a “To Whom It May Concern” letter on behalf of Clyde W. Batchelder, in support of his application for a commission in the Marines (he eventually rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel). In Walt’s letter, he stated that Batchelder had “been with our organization since June, 1934,” and gave his current position “as head of our Camera Department.” If the man standing behind Disney in that George Hurrell photo is not Vee Bodrero it might be Clyde Batchelder.

I am grateful to the following individuals for their help in establishing many key facts in this post about Bodrero’s career in the Marine Corps and at Disney: Dr. Luca de Caprariis, Professor of Modern European History, John Cabot University, Rome, Italy; David Lesjak, author of Service with Character: The Disney Studios and World War II (Theme Park Press, 2014); LtCol Dennis “Lloyd” Hager II, USMC; and Annette Amerman, Branch Head, Historical Inquiries and Research Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, Va.

October 15, 2015:

No Escape

I was in Chicago for a few days last week, on a trip that had no animation/comics connections at all—until, that is, I was walking up North Clark Street, a few blocks south of the Newberry Library, and this sign jumped out at me. Not a bad hotel, either, to judge from the Trip Advisor reviews.

From Garry Apgar: I hope it's not a cathouse. Or did Trip Advisor not go into that?

[Posted October 16, 2015]

A Couple of Barks Thoughts

Geoff Blum, Michael Hodous, and I have just concluded a wonderfully geeky email conversation about Carl Barks's late-1950s work, specifically when and how his drawings showed the effects of the clay-coated paper about which Carl complained on multiple occasions. You can go directly to my post about our exchange, on my errata page for Funnybooks, by clicking on this link for page 326.

I'm very pleased with that errata page in general, not just because it has given me the opportunity to correct my mistakes (very few of them so far, I'm happy to say) but also because it has provided a venue for additional information about the comic books and creators that interest me most.

And speaking of Barks, it has been a while since I recommended the Carl Barks Fan Club Pictorial, published by Joseph and Barbara Cowles, Barks fans of very long standing. The CBFCP has reached its eighth issue (plus a separate "potpourri" compilation of material from a predecessor newsletter), all available through amazon.com. These are beautifully produced books, and if you're a Barks fan and not familiar with the series, you owe it to yourself to sample at least one issue.

October 5, 2015:

A PBS Postmortem

Contrary to my expectations, I did wind up watching most of the first part of PBS' two-part American Experience extravaganza on Walt Disney—at my wife's insistence, since I make two very brief appearances in it. As I first feared and then expected, it was awful. Sloppy, distorted, inaccurate—all of those adjectives could be called into play, with no fear of contradiction from me. Some aspects of the show, like Ron Suskind's prominent role, were simply bizarre. An occasional bright spot, like a bit of unfamiliar archival film, could not come close to making up for the show's shortcomings. I didn't see the last two hours, which may have been a little better. For full evaluations of the show by writers more knowledgeable about Walt Disney, and sympathetic to him, than American Experience's producers, I can recommend posts by Jim Korkis and Todd Pierce. [An October 21, 2015, update: I overlooked an excellent commentary on the PBS show by Floyd Norman, the veteran Disney animator and writer. It's on his blog, at this link.]

I sat for another TV interview ten days ago, in New York—I flew up for the day from Washington, where Phyllis and I were house-sitting for our former next-door neighbors—and I thought it went better than my PBS ordeal. (For one thing, my stomach was much more cooperative.) But as with PBS, I came away thinking that most and maybe all of what I said was destined for the trash.

When I was conducting interviews myself, hundreds of them, for my books and Nation's Business magazine, I always tried to prepare thoroughly, so that I had a lot of questions in mind, and I tried to make the tape recorder as inconspicuous as possible during the interview (I've never interviewed anyone on camera). A good interview, to my mind, was like an extended conversation whose shape was not foreordained, and that just happened to yield words suitable for publication. In my experience, TV people usually approach interviews very differently: they come into an interview with a story line already firmly established, so that your job, if you're the person being interviewed, becomes to provide pithy comments that will amplify what the producers think they already know. Add the bright lights and cables and technicians that TV requires, and when you're being interviewed you can feel like a gangster getting the third degree in an old movie. It's all a matter of money, of course; those machines and those people cost a lot of it, so for a TV producer minimizing uncertainty easily trumps coddling superannuated authors.

TV interviews are made to order for someone like Neal Gabler, who is adept at spotting opportunities to serve up pungent morsels about, say, the darkness in Walt Disney's soul. If, however, in responding to questions you tend to address directly what you think are misconceptions or inaccuracies, you create problems for the producers that they are likely to resolve by eliminating you from the show. In my latest interview, I was so impolitic as to suggest, among other things, that Elias Disney was not an ogre, that the Disney studio was not in financial distress in the 1930s, and that Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was not a daring gamble that many people believed would fail.

On the latter point, the interviewer rather triumphantly pointed out that Walt and Roy had put up their library of cartoons as collateral when they borrowed hundreds of thousands of dollars from the Bank of America to finish Snow White. Didn't that prove something? I was too flummoxed by the question to answer adequately, but of course that transaction proved, if anything, that the bank had a lot of confidence in Walt and in the value of his cartoons, the older shorts and the new feature alike. And there was certainly nothing strange about a bank's wanting collateral for a large loan.

I'll hope for the best from the new show (whose particulars may not have been announced yet, so I won't announce them here). What I won't expect is to see or hear much of myself.

From Thad Komorowski: I'm glad you called attention to Ron Suskind's bizarre prominence in the documentary. For some reason, he gets a special slot because he won a Pulitzer and later wrote a book about how his autistic son connects with Disney movies (and mostly Disney movies made decades after Walt had died).

Okay, that's nice. But where the hell were John Canemaker or Leonard Maltin!? J.B. Kaufman? Jerry Beck? David Gerstein? Jim Korkis? Didier Ghez? Mark Kausler? It's impossible to get everybody, but that list of absentees is pretty incriminating in itself and insists on dismissing the PBS doc out of hand.

For what it's worth, Suskind's Life, Animated is very much written from the "privileged white" point of view. Most parents of autistic children could never afford the caregiving described at length, so it's completely irrelevant in that regard.

[Posted October 6, 2015]