"What's New" Archives: May 2015

May 29, 2015:

May 14, 2015:

A Day in the Life: Disney, June 12, 1935 (Cont'd)

May 12, 2015:

May 29, 2015:

It's a Lulu!

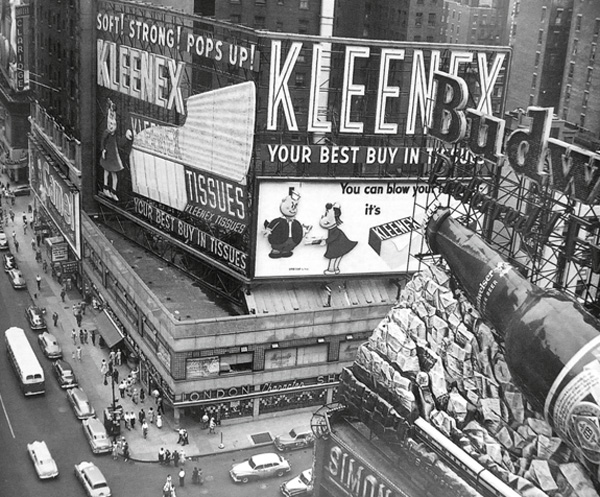

From Milt Gray (and ultimately from the National Archives) comes this circa-1950 photo from Times Square, documenting Little Lulu's strongest and longest-lasting commercial affiliation, with the Kimberly-Clark company, makers of Kleenex. I was reminded, looking at this photo, that Lulu's status was always a little different from that of the other stars of the monthly Dell comic books. The Disney, Warner Bros., MGM, and Lantz characters existed primarily on film; the comic books and other licensed items were spinoffs. The same was true of Roy Rogers and Gene Autry. The Lone Ranger was mainly a radio and then TV character, and Red Ryder the star of a widely published comic strip. Tarzan was omnipresent in books, movies, and newspaper comics. Lulu's fame rested on her weekly gag panel in the Saturday Evening Post, but that stopped a few months before the first Little Lulu comic book appeared. There were Lulu animated cartoons for a few years in the late 1940s, and merchandise of various kinds, but it was as a comic-book character that she had the longest and most profitable life, her popularity owing in very large part to the brilliance of John Stanley's writing..

As a comics-obsessed kid, preoccupied with nerdy niceties of my own peculiar kind, I found Little Lulu's anomalous status vaguely disturbing. There was, it seemed to me, something not quite legitimate about characters that had no life to speak of outside the comic books in which they were featured. The "pure" comic-book characters, like those that filled most of the DC comic books, were a little shabby in my eyes. Memories of such pickiness embarrass me now, but I am, to be sure, still a comic-book snob. It's just that my snobbery has evolved, and it now embraces Little Lulu without the slightest hesitation.

Speaking of comic books...

As I've mentioned, my most recent book, Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books, has been nominated for one of the Eisner awards, usually described as the comic-book industry's equivalents of the Oscars. The 2015 Eisners will be awarded at Comic-Con International in San Diego the evening of July 10. I've never attended one of the San Diego conventions, but this seems like a good year to break my fast, and Phyllis and I plan to be in town for the entire convention. I'm certainly not counting on a victory in my book's "Best Scholarly/Academic Work" category—the competition is intimidating—but if it should win, how gratifying it would be to accept the award in person!

I've mentioned a number of reviews of Funnybooks that I thought showed a welcome understanding of what I was trying to do in the book, but I haven't mentioned until now the glowing review by the leading film scholar David Bordwell on his website. It's tremendously pleasing to earn praise from a writer with a record as distinguished as David's

...and comic-book people...

The name Matthew H. Murphy should ring a bell with readers of Funnybooks. He's mentioned in the book a half dozen times, as the most important of Oskar Lebeck's successors at the head of Western Printing's comic-book operations in New York City. I've just learned from Robin Snyder's invaluable monthly first-person history The Comics! that Murphy died last November 20, at the age of ninety-one. I would love to have met Murphy and talked with him about his time at Western, but by the time I began work on Funnybooks, and approached him through Robin, his health would not permit that. Fortunately, Murphy shared some of his memories with Robin, most notably in a memoir just published in Vol. 26, No. 8, of The Comics! (dated August 2015).

You won't find in Murphy's memoir (or in his letters that Robin has also published) any inconsistencies with what I've written in Funnybooks or what I was told by other Western veterans, but what Murphy writes tends more toward the acid and resentful. Happily, Robin has also published warm comments by Everett Raymond Kinstler, one of Murphy's best collaborators on titles like Silvertip and Zorro. Kinstler remembers Murphy as a "dedicated, decent and good friend," and I'm sure that's an accurate assessment. A subscription to The Comics! (twelve monthly issues) is $30 to Robin Snyder, 2745 Canterbury Lane #81, Bellingham WA 98225-1186

...which ones deserve the spotlight?

Kinstler, like Murphy, is mentioned more than once in Funnybooks. I've become aware since the book was published that I may have ruffled some feathers not through what I say about various artists and writers, but by mentioning some of them not at all. There are artists I wish I could have mentioned, like some of the veterans of the old pulp westerns of the thirties. I'm fond of the comic books illustrated by Albert Micale and Harry Parkhurst (aka Harry Parks), but their work as comic-book artists seems to me less important than, say, Jesse Marsh's on western titles like Gene Autry Comics and Johnny Mack Brown; and although I write about Marsh at some length, it's mainly in connection with his work on the most significant of his comic books, Tarzan.

I think it's important that a book like mine tell a story, clearly and accurately, and there were only so many byways I could explore without losing my story. Such considerations weighed especially heavily when I was writing about the latterday Dell and Gold Key comic books. I have nothing against Dan Spiegle, for instance, but I don't find anything in his work that makes me want to write about it. That's the last thing I could say about Barks, or Kelly, or Stanley, or Toth, or Marsh, or...well, if you've read my book, you know the names, and if you haven't read it, those names should give you some idea of what matters to me in a comic-book story.

And before I forget: I mentioned Milt Gray above, and you can find Milt on camera, talking about Bob Clampett (at a gallery, with Willie Ito in attendance), at this link, for the late Paul Maher's Children's Television Archive. The many brief interviews on that site include some not just with animation people but also comic-book artists who doubled in animation (Pete Alvarado, Owen Fitzgerald). The archive is a little rough and ready, unfortunately, with some badly misspelled names (Leo Salkin becomes "Les Selkin," Rudy Larriva is "Rudy Lavera"), but it's still a valuable resource, one I've only begun to explore. Thanks to Mark Evanier for posting a link.

From Donald Benson: By now you probably saw Mark Evanier's announcement that John Stanley will be honored with a Bill Finger award, created to honor comic book writers (as opposed to artists) who were generally uncredited and unheralded.

Anyway, as a kid I had a more nuanced attitude towards "real" (or at least, respectable) comics.

§ DC superheroes were all legit, whether they were in other media or not. They were respectable IN SPITE OF their TV representations: stodgy B&W Superman, silly Batman, and those Filmation shows. DC funnybooks were always suspect, because I always envisioned them as outside DC's wheelhouse—like ordering a salad in a pizza parlor. The ones that crossed my path were fun—even Bob Hope—but I just never granted a DC funnybooks in general a free pass.

§ Marvel heroes were legit and had a greater cool quotient than DC, but zero cred on TV. I grew up in the era of HB's Fantastic Four, Gantray's Spider-Man, and the hilariously cheesy Marvel Super Heroes.

§ Anything with a Disney label was legit, even characters who rarely if ever got animated. Once you got past a handful of marquee characters the Disney comic universe was purely a print thing. Gyro Gearloose and his mute assistant actually had more comic book legitimacy than Ludwig Von Drake, who always felt like stunt casting when he appeared in print. And Scrooge McDuck was only an extra in the Mickey Mouse Club title sequence and the host of a '60s "educational" short.

§ The same applied to the comic book worlds built around the HB, Warner and MGM characters, even when they strayed far from their roots (mute characters talking, predator and prey suburbanized, etc.). This isn't to say they were all good; but they were "real." Harvey made Baby Huey more enjoyable than his animated self, starring him in wolf-free comedy tales accompanied by his frazzled father (who only scored one appearance in the cartoons—not sure if that preceded or followed his comic book debut).

§ Comic books based on comic strips were troublesome, because I knew even then they weren't the work of the guys who did the real versions in the newspapers. Comics I didn't know were based on funnies were cool: I knew Lulu only as a comic book; likewise Sad Sack. Also Dennis the Menace—even with diluted menace the comics felt right, and I was a big fan of those 25-cent specials where he went to Mexico, Hawaii, and Hollywood.

§ Dell and Gold Key ruled the funnybooks, but I tended to look askance at their superhero / adventure titles. It was the inverse of my DC prejudice: I imagined a roomful of duck and mouse guys brainstorming action heroes. And the cover illustrations were always more booklike than comiclike. It may have been better artwork, but it wasn't a comic.From Milton Gray: Wow, I was very surprised to read on your website that there was some video footage of me on the internet! When I watched it, I recalled that it was shot several years ago — I’d guess about 20 or so years ago — at an animation art gallery in West Hollywood. I don’t recall being told ahead of time that I would be asked to give a talk, I think it was just an impromptu thing, and the event had something to do with Clampett’s work, among other things. I also have no memory of being videotaped, although I probably did see someone with a home video camera and didn’t give it any serious thought. Just assumed it was someone shooting some amateur home movies. But I did get a kick out of seeing the footage. My six minutes of fame….

[Posted May 30, 2015]

May 14, 2015:

A Day in the Life: Disney, June 12, 1935 (Cont'd)

I've added the photo above to my Essay on Walt Disney's arrival in London, and I've revised the text again to take better account of all the new information about the 1935 trip revealed in Didier Ghez's Disney's Grand Tour. You'll notice when you go to the Essay page that this photo is wider than the others there, but that's because I've been working with wider layouts and larger pictures for the last few years, and I decided not to shrink this one just to make it uniform with the others on the page.

May 12, 2015:

When the Eyes Don't Have It

Thanks to some minor but necessary eye surgery, I've been unable to read comfortably or spend much time on the computer the last ten days. I've made up for that lack in part by listening to the Amos 'n' Andy radio show from the early and mid-1940s, testing further the conclusion I reached in work on Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books, that Walt Kelly found in that show, and especially in its characters, raw material that he shaped into the "Albert and Pogo" feature in Animal Comics and ultimately into the Pogo comic strip. After listening to a few more hours of the show, and hearing some episodes for the first time, I'm still sure I'm right. I wondered if some Kelly fans might bristle at such a conclusion, but offhand I can recall almost no comments either way. Mark Mayerson wrote: "I hadn't made the connection between Kelly's dialogue and Amos and Andy, but it's obvious now that you pointed it out." But that was about it.

Not that there's much reason to bristle if you actually listen to the radio shows, which presented Amos and Andy and their friend the Kingfish less as African Americans than as transplanted country bumpkins in the big city (New York). References to the characters' race were absent from the shows I listened to, and it was striking how often that unmistakably white characters, including a number of familiar Hollywood names, addressed Amos and Andy as "Mr. Jones" and "Mr. Brown," without a hint of sarcasm. (As "you boys" sometimes, too, but usually as the equivalent of "you guys," and not in a way that seemed racially condescending.)

Amos and Andy were of course played by two white men, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, but at the close of one show I listened to, they spoke in character but in standard English—very much as if they were black actors who had been playing characters less sophisticated than themselves.

Gosden and Correll performed in blackface in the 1931 movie Check and Double Check, a dreadful mistake that they did not repeat, but they did pose for publicity photos in blackface, as in the example from the early 1940s here. Amos 'n' Andy's saving grace was that it did not traffic in minstrel-show stereotypes, a virtue that was devalued when its creators wore blackface. When Amos 'n' Andy moved to television in 1951, the cast was made up of veteran black actors like those who had played supporting roles on the radio show, but it was too late to start over. Since then, comedy all but indistinguishable from Amos 'n' Andy has reappeared on TV many times, in shows like Sanford and Son, but the actors (if almost never the writers and directors and producers) have always been black. That makes a difference, as it should.

Anyway, to get back to Walt Kelly. If, as I believe, he found Amos 'n' Andy a fruitful source of comic ideas, that says nothing about his thinking on race, which I'm sure was never backward and was by the late 1940s certainly more advanced than that of a great many other white Americans. Just as William Shakespeare found the raw material he needed in Elizabethan melodramas and Hollinshed's Chronicles—sources no one reads for their own sake today—Kelly found a starting point in Amos 'n' Andy.

As in that earlier instance, a great creative mind can turn lead into gold. One thing that's clear from marathon listening to Amos 'n' Andy is that, even as sitcoms go, it usually wasn't very good, whereas Kelly's Pogo of the 1940s and early 1950s was a work of comic genius with few peers in any medium. Kelly repaid his debt to Amos 'n' Andy many times over.

From Randy Watts: There's an excellent book by Elizabeth McLeod, titled The Original Amos 'n' Andy: Freeman Gosden, Charles Correll and the 1928-1943 Radio Serial, which discusses Amos and Andy's long run as a daily serial in an informed, sympathetic and understanding way. Well worth reading if you're interested in more on Gosden and Correll and their creations.

MB replies: I concur in Randy's endorsement.

[Posted May 13, 2015]

From Donald Benson: Chances are there's zero you don't already know, but I'm in a bloviational mood.

Gosden and Correll voiced a couple of Amos and Andy cartoons for Van Beuren; they're on Thunderbean's "Uncensored Animation from the Van Beuren Studio" disc. The cartoons are not good. Also, the stars either didn't get cartoon voice acting or just weren't interested.

Decades later they did an animated television series, Calvin and the Colonel. By voicing animals of indeterminate race (albeit clearly Southern), they evidently intended to avoid the Amos and Andy stigma. The characters were a bit different: Calvin had Andy's voice but was more laid back, while the Colonel was much closer to the Kingfish with his schemes and shrewish wife. Weak sitcom scripts and canned laughter, but at least the stars' voices seemed to connect with the visuals. Calvin and the Colonel somehow turns up on public domain animation collections.

Van Beuren tried again with the African-American comedy team Miller and Lyles, but Lyle's untimely death caused them to salvage what they had into a Tom and Jerry titled Plane Dumb. That's the one where Tom and Jerry are flying to Africa, then slather on blackface and become Miller and Lyles until the closing shot of the cartoon.

Next time you're in a radio mood, I recommend the BBC Sherlock Holmes with Clive Merrison and Michael Williams. They require serious listening, since they're more "cinematic" in their writing and editing.

[Posted May 16, 2015]

From Claus Simonsen: I’m a Barks and Kelly admirer from Denmark, vintage ’55, and have just finished reading Funnybooks. The book was a pleasure from start to end, and I enjoyed your comments on both Barks and Kelly … your Amos and Andy connection is as I see it in line with Kerry Soper’s observation of the likenesses between Pogo’s Animal Comics world and the “Uncle Remus” stories of the 19th century in his book We Go Pogo… both you and Soper find likenesses between Kelly’s swamp world and depictions of black life around the turn of the century, and I’m sure you’re right.

It was very interesting having some light shed upon the Western Publishing editors. Barks mentions Craig, Cobb and many others in several of his letters, but they have always been somewhat distant to the ordinary comics fan. Your book helped putting personalities behind the names. Buettner on the other hand has been well-known for quite some time, mainly because he was a sometimes cartoonist himself, mostly of undistinguished art and stories. But ... I for one do like his “Li’l Bad Wolf” stories in the ’45-‘46 Walt Disney'sComics & Stories quite well—they contain some of the wildness and danger that’s missing from later stories with these characters. WDC #65 is one of my favorites, zeroing in on Big Wolf’s dilemma: on one hand eagerly building up and maintaining his image as someone to reckon with, while on the other hand having a very hard time living up to his own expectations and the ones of his surroundings, as it turns out that he’s just a normal Joe.

One aspect I had hoped you’d enlighten, was the period from the last half of the 50’s ’til the early 60’s when many Western/Dell publications were published in two versions—one with advertisements on back cover (and sometimes on inside pages as well), and one without ads. If this was Western’s way of testing the market, it seems queer that the practice was continued for half a decade. Does anyone know why this was done, and/or if there was any difference between the distrubution of ad/non-ad variants. You touch the subject of ads in chapters 23 and 25, but as far as I can see the problem sketched here is not covered. The ad/non-ad variants have puzzled me as well as fellow collectors for years … can you enlighten me?MB replies: I'd guess that those Dell comics published in two versions, one with ads and one without, were simply a "split run," a way of selling ads at a lower cost because they were reaching fewer readers.

From Byron Vaughns: After reading the recent comic book reprints of the early "Pogo" stories, I believe your supposition of "Amos 'n' Andy" as a major influence on Walt Kelly's work is probably correct. However, Kelly's southern fried writing also reminded me of the "Br'er Rabbit" books.

A few years back I had the opportunity to direct a long form animated cartoon, The Adventures of Br'er Rabbit, and looked up the old source material. The language in the "Br'er Rabbit" books was quite labored and sometimes difficult to interpret (similar to the some of the "Pogo" comic books of the forties). On occasion it reads like a foreign language.

I think Kelly took a lot of inspiration from both the radio series and the original "Br'er Rabbit" books, then eventually streamlined "Pogo" along the way to appeal to more people. Regardless of the source material, the "Pogo" comic books and early strip were so rich with genuine wit and humor.MB replies: After reading all of the Uncle Remus stories, I see very little similarity between them and Kelly's Animal Comics stories, except that the characters in both are animals living in the South. I write at length about such influences in the sixth chapter of Funnybooks, titled "Animal Magnetism."

[Posted May 18, 2015]