"What's New" Archives: June 2014

June 27, 2014:

Book Backlog II: The Fairest One of All

June 19, 2014:

Carl Barks's First Published Drawing...

June 14, 2014:

For Father's Day: Walt and Diane, 1943

June 11, 2014:

June 7, 2014:

June 2, 2014:

June 27, 2014:

Book Backlog II: The Fairest One of All

In which I continue playing catch-up with books I've wanted to review but haven't, because I was writing another one of my own.

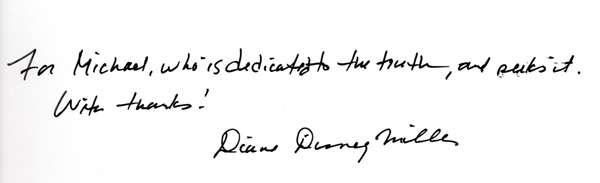

I own two copies of The Fairest One of All: The Making of Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs by J.B. Kaufman, the splendid book published by the Walt Disney Family Foundation Press in 2012 to commemorate the seventy-fifth anniversary of the film's release. Kaufman and I have known each other for a long time, and I read the manuscript in 2007 at his request. The copy I received from him bears a warm and collegial inscription, and I can't imagine ever wanting to part with it. But I value my other copy of the book even more, especially because the person who wrote on that copy's flyleaf died the year after the book was published. This is the inscription:

And thanks to you, Diane, for all your good works, especially the Walt Disney Family Museum and the Walt Disney Concert Hall, both worthy monuments to your father.

As far as I'm concerned, Snow White was the greatest of Walt Disney's's achievements, a fabulous movie in its own right and the foundation of many great films to come, features and shorts, from Disney and other studios. We're very fortunate that J.B. Kaufman, who was then on the staff of the Walt Disney Family Foundation, Diane's organization, was available to write about it. Of the writers whose books have appeared not just with the Walt Disney Company's blessings but also under a Disney imprint, only Kaufman and John Canemaker have done the work to qualify fully as experts on their subject matter.

The Fairest One of All is rich with well-documented facts (as I knew from reading the manuscript) and richly illustrated, too (as I expected but did not know, since I saw none of the illustrations beforehand). I can offer only two—not exactly caveats, but comments.

The book is not organized chronologically, except in the general sense that it opens and closes with sections dealing with events before production began in 1934 and after the film was released at the end of 1937. In the body of the book, the chapters are broken down mostly by categories (character design, music) and by sequence. Thanks to Kaufman's skill, this turns out to be a perfectly workable plan, lacking only the drama that a chronological treatment could offer by showing us Walt and his people evading one catastrophic trap after another. It was that drama that I tried to capture—successfully, I think—in my own Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age.

The larger but subtler problem, if I can call it that, is the same one I wrote about a few years ago in the piece I called "The Approved Narrative," a review of what were then Kaufman's and Canemaker's two most recent Disney books. I lamented what I called the lack of an authorial point of view in books published under a Disney imprint—an inevitable lack, since in such books The Walt Disney Company (to use the currently preferred corporate title) is in effect writing about itself. Fortunately, the stronger the subject matter, the less claustrophobic this arrangement. Where Snow White is concerned, the film is so remarkable, and the story of its production so rich and absorbing, that any reservations about a book's Disney credentials melt away in the face of an authorial performance as strong as Kaufman's. I can't imagine that the book would be very different, and certainly not much better, if Kaufman had written it without any official Disney involvement at all.

It's when a film is more problematic that an independent authorial voice could make a difference. Kaufman has been completing a comparable volume on Pinocchio, the second Disney feature and a movie that, for my money, suffers from failings much more serious than any lapses in Snow White. I wouldn't expect Kaufman to agree with that assessment, but I'd like to read what he might say in response to criticisms of Pinocchio like those I make in Hollywood Cartoons. I doubt that he'll address them. I'm reminded of what I wrote on this site five years ago:

We've ... seen a radical transformation in the number and nature of richly illustrated, adult-oriented books about the Disney cartoons. [In 1973], when Abrams published Christopher Finch's Art of Walt Disney, that book—coming as it did from a respected art-book publisher, and coming also many years after the last book that was at all comparable—got an extraordinarily large amount of attention, and also sold extremely well. Now, though, heavily illustrated Disney books are thick on the shelves, and most of them bear Disney's own imprint.

One justly esteemed author of such books [not J.B. Kaufman] lamented to me a few years ago that his books rarely get reviewed, thanks no doubt to their "Disney Editions" label, but from Disney's point view, that can't matter much: there's a sizable core of fans who will buy most such books, and Disney doesn't have to share the money with an outside publisher. More and more, I'm sure, it will be writers who are paid by Disney who will be telling us about Disney history, new Disney films, and so on. And if Disney has its way, most Disney fans will not look anywhere else—or take their money anywhere else—for their Disney dose.

The greatest hazard in such arrangements is not error but dullness. There's evidence for that in the "making of" features that accompany the new Blu-ray releases of Sleeping Beauty and Pinocchio. The histories of both of those lavish failures are vastly more interesting than you could guess from what those of us who appear on the screen say about them (I appear briefly in both features). What's left is not wrong, exactly, but it's safe and controversy-free. It's also not very interesting—unless one is a diehard Disney animation freak who can't hear the same stories too many times. Such people are, of course, the target audience.

Christopher Finch wrote about Snow White in The Art of Walt Disney, of course, and that chapter is one of the best in his book. But how much better Kaufman's book is, how much richer in every way, not just because his whole book is devoted to Snow White, but mostly because Kaufman writes about it as someone who loves the film, and Walt Disney, as few other people do, and who knows that one of the best ways to express such love is through a devotion to historical accuracy, and historical completeness.

J.B. Kaufman has left the staff of the Walt Disney Family Foundation under cloudy circumstances, and I have no idea if he will be writing again for Disney, once the Pinocchio book is done. We can only hope so.

How to Train Your Dragon 2

This was a movie I wanted to like, because—as evidenced by the review I posted here more than four years ago—I enjoyed the original How to Train Your Dragon a great deal. Instead, I left the theater disappointed. Everything I most liked about the first movie—especially the sensitively depicted bond between boy and animal, and the aerial displays so breathtaking in 3-D—had been diminished or discarded in favor of the overbearing buzz and clatter that I associate with DreamWorks Animation features in general (not that I've seen very many in the last few years).

Seeing Dragon 2 in IMAX 3-D turned out to be a mistake, this being a movie that grabs you by the throat and shoves itself in your face for much of its length, a particularly disagreeable experience when the screen is IMAX-huge. The noisy concluding battle that deformed the first feature now seemed to consume almost the entire movie; I suppose this is what people mean when they say the story is "darker." Everything was tiresomely familiar, excepting only the reappearance of Hiccup's mother—really the only justification for this sequel—and that revelation was, for me, all but smothered by the general excess. (She looked naggingly familiar, until I finally realized that her design was probably borrowed from the dud 2008 feature The Tale of Despereaux.) I even kept being aware of the music, and actively disliking it because it underlined so crudely what was too obvious to begin with.

It's tempting to speculate about what went wrong. Dean DeBlois, co-director of the original How To Train Your Dragon, was the solo director and writer of this one, but I don't know that the absence of Chris Sanders as co-director was a critical lack. Sanders was the co-director of another DreamWorks feature, The Croods, that was widely dismissed as heavy-handed comedy when it came out last year. I haven't seen it yet, although I keep telling myself I should stream it. Maybe I should leave well enough alone.

In fairness, I should point out that the two little girls, ages 9 and 10, who accompanied me to Dragon 2 disagreed only on whether it was the best movie they'd ever seen or just one of the best. Further proof, I'm sure, that I should stay home and watch Looney Tunes on Blu-ray.

From Kevin Hogan: I would agree that the “joy” of the original was absent, although I was a bit less frustrated than you appear to be when I saw it. I was prepared for it to take the Empire Strikes Back route of darker sequels. I don’t think they had much further to go with the “boy and his animal” angle, and so they went for loud, large, and serious.

I do think that the film was an improvement for DreamWorks in the animation itself. I thought the combination of the slightly more natural acting and the cartoony character designs was a bit of a clash, but I at least give them credit for trying.

MB replies: Disappointed, yes; frustrated, no, because I regard anything good that comes from DreamWorks, like the original Dragon, as a gift.

[Posted June 30, 2014]

From Win Leerasanthanah: I stumbled upon your website from David B. Levy's handbook for animation students, and I was intrigued by your article on How to Train Your Dragon 2. I was relieved to realize that I wasn't the only one who is disappointed with the movie, while all my friends find the film to be amazing in some way.

The whole time I was watching, I was thinking, "Gosh, how on Earth did DreamWorks spend $149 million to create a grandiose but disorganized movie?" The themes go all over the place, and the direction of the movie was never clear to begin with. His mother's appearance is a great lift to the story, but she can only go so far to connect other characters when she is clouded by dragon battles with their "money shots."

By the time the movie ties in all the themes together, I was already nervous with the film to flop out for such a high budget. (DreamWorks fired hundreds of animators after that). I hope DreamWorks learned a lesson from this, and hope that they create films that will win our hearts.

[Posted July 10, 2014]

June 19, 2014:

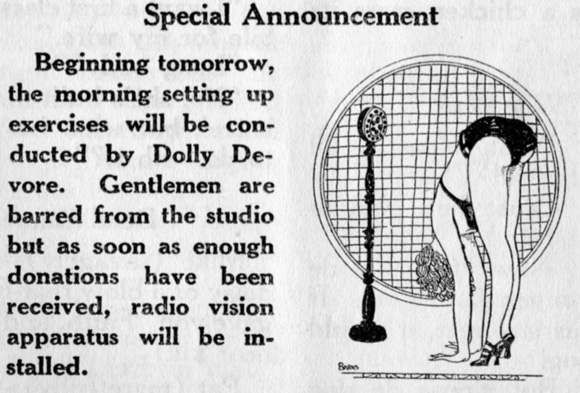

Carl Barks's First Published Drawing...

...was quite likely this one, which appeared (in much smaller size, so that reading his credit all but requires a magnifying glass) in the Calgary Eye-Opener for June 1928. That this was Barks's first signed drawing in the Eye-Opener is the considered judgment of Geoffrey Blum, who has edited two collections of Barks's Eye-Opener drawings, and I'll happily accept that conclusion, since the June 1928 number is one of the twenty-odd issues of the Eye-Opener in my own collection. There are other private collections much larger than mine, but collections in public and university libraries are few and thinly stocked, so anyone who wants to challenge Geoff's conclusion has his work cut out for him.

It's conceivable, I suppose, that the Eye-Opener published unsigned Barks drawings in earlier issues, but that seems unlikely; and just as unlikely is that Barks was published in other magazines first. He was still working as a laborer in 1928, and was years away from joining the Eye-Opener's staff.

From Garry Apgar: Was Carl Barks illustrating a primitive form of twerking here? Could Dolly Devore be Miley Cyrus's great-great maternal grandmother? "Enquiring minds want to know." Of course ... such speculation may just be, as the Brits would say, Barking mad ...

[Posted June 27, 2014]

June 14, 2014:

For Father's Day: Walt and Diane, 1943

Tomorrow is the first Father's Day since Diane Disney Miller died last fall, and it seems an appropriate time to post a photo of her with the father to whom she was so devoted. This photo was taken at the Drake Hotel in Chicago on August 21, 1943, as Walt and Diane (who was 10) were returning from a trip to the East Coast and Detroit. I'd planned that this photo would be part of a post on that trip, perhaps as one of my "Day in the Life" photo essays, and you may see it again sometime soon. Diane shared her memories of the trip with me, and they will of course be an important part of my post.

June 11, 2014:

Concepts, Cont'd

I wrote a couple of weeks ago about the dustup over Amid Amidi's dismissal of a book devoted to the "concept art" for the Disney feature Planes and its sequel. I said, among other things: "The feeling I get ... is that there are a lot of people in Hollywood animation today who want their day-to-day work to be judged, and especially praised, as if it were the fruit of a personal passion, as if it were in some sense art, and not as what it really is, a mundane way to put food on the table."

I realized later that I should have made allowance for the possibility that personal passion and day-to-day work can in fact coincide, and that it isn't inevitable that real satisfaction from work will come only away from one's day job. After all, that's why the "golden age" of Hollywood animation was golden, back in the 1930s and '40s and '50s. Many of the people who worked then in the best Hollywood studios discovered that their own artistic ambitions were aligned, substantially if not always perfectly, with the ambitions of the people who were in charge of making the cartoons. I remember one veteran animator's telling me that after he moved over to Disney's from the Mintz studio in the '30s, he couldn't wait to get to work in the morning. I was impressed; I don't remember ever feeling that way about any job I've held. But other people said much the same thing: the work was challenging, it could be fun, it was rewarding in many ways. (If anyone who worked on Planes felt that way, please raise your hand.)

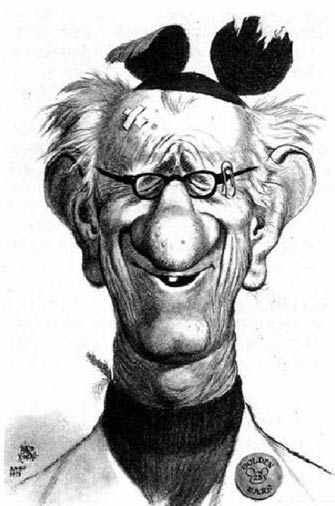

Even in a "golden age," of course, there will be people who think only in adversarial terms and regard the work, and the people who've hired them, with the intense cynicism I remember seeing so often in my colleagues when I was a newspaper and magazine journalist. The purity of such people's disdain for the work, and for their employers, can be a little unsettling. I wrote on this site about interviewing one such person, Phil Klein, a few years ago, and you can read about someone who seems to have been cut from the same cloth, Larry Clemmons, in the second installment of Steve Hulett's marvelous memoir of his early days as a story man at Disney, Mouse in Transition, which is being serialized at Cartoon Brew. Clemmons worked at Disney in the 1930s, mostly as an inbetweener and assistant animator, and returned in the 1950s as a writer for TV and then feature cartoons, after years of writing for the Bing Crosby radio show. (That's him at the right, in a caricature by Ward Kimball that I've appropriated from Cartoon Brew.) In a quotation that presumably comes from memory but sounds completely authentic, Hulett has Clemmons saying this:

Even in a "golden age," of course, there will be people who think only in adversarial terms and regard the work, and the people who've hired them, with the intense cynicism I remember seeing so often in my colleagues when I was a newspaper and magazine journalist. The purity of such people's disdain for the work, and for their employers, can be a little unsettling. I wrote on this site about interviewing one such person, Phil Klein, a few years ago, and you can read about someone who seems to have been cut from the same cloth, Larry Clemmons, in the second installment of Steve Hulett's marvelous memoir of his early days as a story man at Disney, Mouse in Transition, which is being serialized at Cartoon Brew. Clemmons worked at Disney in the 1930s, mostly as an inbetweener and assistant animator, and returned in the 1950s as a writer for TV and then feature cartoons, after years of writing for the Bing Crosby radio show. (That's him at the right, in a caricature by Ward Kimball that I've appropriated from Cartoon Brew.) In a quotation that presumably comes from memory but sounds completely authentic, Hulett has Clemmons saying this:

All this crap about the Golden Age of animation? Back in the thirties? It wasn’t MY Golden Age. It was the middle of the damn depression. There weren’t any damn jobs. And there I was, doing breakdowns on a damn Donald Duck short. And then the production manager would walk in and say, ‘We gotta get this picture out! Who wants to come in Saturday and work?’ If you wanted to keep your job you raised your hand and shouted how much you wanted to spend your Saturday there. For no pay. Like I say, it wasn’t MY Golden Age.

I remember other people speaking about their early days at Disney in very much the same terms—the tedium of the work, the despair it induced, the miserable bosses—but for someone like, say, Eric Larson, those grueling early days were just the prelude to a long and highly productive career. Other people, not catching any glimpse of such a future, simply left, if they weren't fired first. Someone like Clemmons, who evidently remained a cynical inbetweener in spirit for decades, was a rarity. I never got around to interviewing him, unfortunately, although I may have hung back because I had a pretty good idea of what I'd hear. Working under George Drake in the 1930s and Woolie Reitherman in the 1960s and '70s would tend to warp one's view of the world.

Of course, the Disney studio in the 1970s was the heyday not just of Reitherman but also of Don Bluth, and it was warped in many ways. Steve Hulett began working there in 1976 (and had a family connection before that through his father, Ralph, for many years a background painter at the studio), and his memoir is powerfully evocative of an institution in decline. I was visiting the studio every year or two then, starting in 1969, and it felt to me like the place Steve Hulett describes, the Hollywood equivalent of a backwater college where exciting new ideas were supposedly encouraged but were in fact regarded as unwelcome intruders that must be smothered quietly. "It ... dawned on me that the simple, direct route wasn’t the way things were done at Disney," Hulett writes. "It meant ruffling too many feathers that were best left smooth and undisturbed."

Mouse in Transition is appearing on Cartoon Brew in weekly installments; the fourth is to be published today. I'm very much looking forward to it, and to what's to come.

The site went up about eleven years ago. In that time I've made a few minimal changes in its templates, but I haven't paid much attention to their elements. It dawned on me the other day that my photo at the top of the page, which was taken in 1997, was badly out of date. I don't look radically different, but my hair is much grayer, and to leave up so old a photo seems a little silly. So I've taken it down from the home page, and I'll remove it from other pages as soon as possible. If for some reason you want to see a photo closer to what I look like now, click on "bio" above. And if for some reason you want to see what I looked like many years ago, as when I visited J. R. Bray and Bob McKimson, there are such photos scattered throughout the site, too.

June 7, 2014:

Another Disney Myth

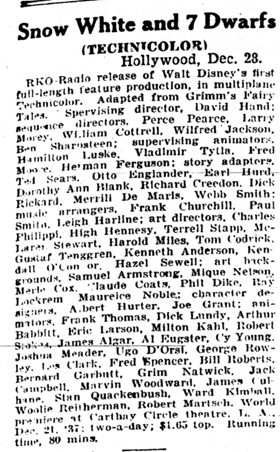

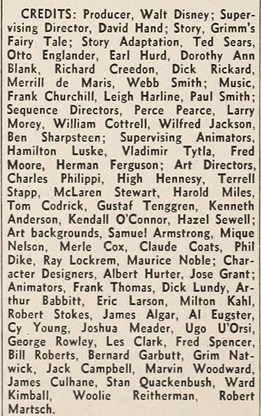

They grow like weeds, don't they? The latest slur, which has been called to my attention by two different people, is that Walt supposedly denied his animators screen credit on the initial release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the credits that all of us have seen having been added only after the 1941 strike and at the cartoonists' union's insistence. As "proof," there are such sources as the skimpy credits that accompanied the rave review for Snow White in the New York Times and statements in notoriously unreliable books like Leonard Mosley's Disney's World.

So, just for the record, here are the credits that appeared in weekly Variety for December 29, 1937 and Film Daily for December 27, 1937. Both include full lists of animators (and others) who got screen credit. The Variety reviewer marveled at the large number of names and wrote of watching them appear on the screen. Film Daily's reviewer praised the four directing animators by name, in addition to listing them in the screen credits.

First the Variety credits:

And then Film Daily's:

I haven't compared these lists with each other, or with the credits in the film as released on video, most recently in an excellent Blu-ray transfer, so it's possible there are small discrepancies of the sort that get into any newspaper. The larger point is, of course, that Snow White as originally released included an abundance of screen credits, for animators and others; and they don't whiz by, to cite another complaint I remember reading many years ago.

Bogus stories like this one always defy belief on any number of points. In this case, if Walt were going to award screen credits to other members of his staff, why on earth would he exclude his animators, the people who were most critical to achieving the result he wanted on the screen and who would be his mainstays for the additional features he wanted to make? How could such an injustice have escaped widespread notice for so many decades?

As to why such stories continue to flourish, your guess is as good as mine. To the extent they originate in the animation industry itself, I suppose jealousy and self-pity (why isn't my genius being recognized?) are the likeliest culprits.

From Donald Benson: The Disney Version also mutters about animators' names being overpowered by Walt's own—which is the deal with any feature film. Especially when the producer or director is a brand, as Walt Disney consciously made himself early on.

It's tempting to argue that Walt's self-branding was another response to losing Oswald—the distributors couldn't take away his own name—but Max Fleischer was already playing himself on-camera as the creator of his cartoons, and Walter Lantz did the same in his very Inkwell-like early work. And Paul Terry's Terrytoons . . . It seems every independent (and contractors like Schlesinger) tried to build name equity they could carry around with them.

Also: feature credits were pretty short in days of yore, designed to zip by quickly before the show. Even the then-epic Pink Panther opening shows comparatively few names compared to a modern film.

MB replies: Here's what Richard Schickel says, on pp. 190-91 of the original 1968 edition of The Disney Version:

Then there was the matter of credit; excepting only Ub Iwerks' brief appearance on the credit card, no name but Disney's ever appeared on his films, a rule that perhaps was good showmanship but not one calculated to win the hearts of his employees. With Snow White he finally yielded on this matter. But on his first feature he carefully gave so many credits—and his name, in contrast, appeared in such very large type—that the effect was the same. Lost in the crowd, the individual craftsman merely suffered a new form of anonymity.

This is underhanded writing of the kind that Neal Gabler refined more than thirty years later: not condemning Walt outright but describing his actions in slippery language calculated to inspire distaste in the educated but gullible reader, of whom there have long been many where Walt Disney is concerned. (For an example of Gabler's writing of the same kind, follow this link.)

"Good showmanship"? Of course. "Walt Disney" became, and still is, more a brand than a man. That was exactly what Walt intended, and that conflation of man and brand was important to the success of the Disney films. Many members of his staff understood that, and, in any case, they knew that Walt's rivals were scarcely more generous with screen credits (on their inferior cartoons) than Walt was.

Once the Disney brand was well established—that is, by the time of Snow White—Walt became generous with screen credit for his features. He was more generous, in fact, than most producers of films of all kinds in the mid- to late 1930s. The Snow White credits are, however, much less abundant than the credits in modern films, and, again unlike modern films, they appear on the screen at a pace that makes it possible to read all the names on a card before the next one appears.

So, it's hard to see how the "individual craftsman" recognized on the screen could have felt "lost in the crowd." If Walt had been stingier with credits on Snow White, so that the names of some of those craftsmen were more prominent and others missing entirely, Schickel would no doubt have found cause for condemnation in that. If you're Walt Disney, in the hands of such authors, you just can't win.

[Posted June 9, 2014]

June 2, 2014:

Felidae

I see almost no new animated movies except for those that there's no escaping, like Frozen. I do revisit old features that I haven't seen for a while, and occasionally an older film I hadn't known about will come to my attention, thanks usually to one of my correspondents. Such was the case with Felidae, a German animated feature from 1994, directed by Michael Schaack. I'd never even heard of it until I got a message a couple of years ago asking if I'd seen it. The complete film could be found on YouTube in an English version, I was told, but I held off because I hate watching movies on a computer screen. When YouTube became available streamed through Roku, Felidae was one of the first things I wanted to see.

I see almost no new animated movies except for those that there's no escaping, like Frozen. I do revisit old features that I haven't seen for a while, and occasionally an older film I hadn't known about will come to my attention, thanks usually to one of my correspondents. Such was the case with Felidae, a German animated feature from 1994, directed by Michael Schaack. I'd never even heard of it until I got a message a couple of years ago asking if I'd seen it. The complete film could be found on YouTube in an English version, I was told, but I held off because I hate watching movies on a computer screen. When YouTube became available streamed through Roku, Felidae was one of the first things I wanted to see.

The movie is based on a novel by a Turkish-born German writer, Akif Pirincci, whose great success with the book and subsequently the film was the subject of a New York Times story in December 1994. The Times summarized book and film this way:

A detective story in which a mass murderer, the sleuth who unmasks him, and most of the other principal characters are cats, "Felidae" is also full of darker overtones. The murderer is a sort of feline Josef Mengele who tries to create a master race of cats fierce enough to take the world back from their human oppressors, and who kills off those who fail to follow the strict breeding rules he sets for them.

An English translation of Felidae had been reviewed in the Times early in 1993, its plot dismissed then as "too much talk and too much philosophy." As best I can tell, though, the movie never had a U.S. release.

And no wonder. However peculiar the book, the movie is surely even stranger. Not just because of its insistently bloody and kinky events, but also because it is drawn and animated in a style I can best describe as pseudo-Don Bluth. Bluth animation, as I've described it, "is not merely literal but also painfully self-conscious. It is the kind of animation that results when animators try to achieve the vaunted Disney 'sincerity'—that is, animation in which the characters really seem to believe in what they're doing—by having the characters behave as if they know that they're appearing in a film." There is also in Felidae a hopelessly clumsy and complicated plot, another characteristic of Bluth's features, and a similarly characteristic longing for a Disney-style cuteness that is in this case radically at odds with the subject matter.

I can easily imagine a harried suburban mother dumping her kiddies at a multiplex showing Felidae, only to come back a couple of hours later and finding them traumatized. I'm sure American distributors had exactly the same thought. The animated feature, as American filmmakers, distributors, and exhibitors have defined it, is far too narrow to accommodate a film like Felidae.

Fortunately, most of my visitors are older and tougher than the American children who will never see Felidae. If I can't exactly recommend Felidae to you, I can at least say that it will probably do no more damage to your psyche than most recent American feature cartoons.

From Andrew Osmond: I chuckled when I read your post about Felidae—it threw me as well when I saw it! Just for your information, there was a comparably 'dark' talking-animal film made in San Francisco a decade earlier, which for my money was far superior. It was 1982's The Plague Dogs, directed by Martin Rosen a few years after he made Watership Down in London. Watership was rather violent itself, of course, but Plague Dogs was positively nightmarish... and, of course, it bombed in cinemas.

I know you found Watership Down terrible, though my impression is that the animation in Plague Dogs is rather better, and other aspects of the film—the background art, the voice-cast (including John Hurt)—lift it up. It's the story of two dogs which escape from an animal experiments laboratory, and are hunted as possible plague carriers. Personally I found it rather haunting. The setting is England's Lake District, where I've never been, so my image of the area is largely derived from the film! Like Watership Down, it was based on a novel by Richard Adams; the author said he found it a better adaptation than its predecessor.

Browsing your site, I've just found that I plugged Plague Dogs some years back at this link but I suppose there's no harm in bringing it up again in connection with Felidae.

MB replies: My own less than favorable comments about Martin Rosen's version of Watership Down are at this link. I still haven't seen Plague Dogs and probably won't.

[Posted July 1, 2014]