"What's New"Archives: January 2011

January 31, 2011:

Where Walt Was: November 8, 1965

January 29, 2011:

January 18, 2011:

January 12, 2011:

January 11, 2011:

January 7, 2011:

January 6, 2011:

January 31, 2011:

Where Walt Was: November 8, 1965

This unusual photo of Walt Disney came to mind after I saw the excellent new movie The King's Speech, with its portrayal of the British royal family. One of the film's characters, Princess Margaret Rose, made a three-day visit to Los Angeles in early November 1965, in the company of her then husband, the Earl of Snowdon (the photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones). On Monday, November 8, they visited Universal City Studios and watched a little of the filming of Alfred Hitchcock's Torn Curtain. Sound stage 12 was turned into what one newspaper report called a "Grecian garden" for a luncheon honoring the royal couple, and Walt was one of the many Hollywood celebrities who were guests. In the photo, he is being presented to Margaret by Dr. Jules C. Stein, the founder and chairman of MCA, Universal's parent company, who is at Walt's left.

[A February 7, 2011, update: Thanks to François Monferran for pointing out that newsreel footage of Princess Margaret's visit to Universal City is at this link. Also, for the sake of clarity: Jules Stein is the bespectacled man in the photo above; he's at Walt's left (and that's apparently Walt's left hand on his shoulder), but on the right side of the photo.]

From Steven Hartley: I came across your post, and it's very interesting to see Walt Disney visit the Royal Family. Although, what I'm really interested in talking about is The King's Speech.

I saw the film last week, and I thought it was a very, very great film. It's just the perfect film for me, because King George VI had a stammer problem and I go to a speech-and-language school and I really understand how George felt when he had difficulties with his speech. I was very deeply moved by the film, particularly the ending when the King finishes his speech and is praised by the broadcasters and the public. I thought it was superb, and it did leave me with tears rolling down my cheeks.

Because of the movie and because 2011 is the "National Year of Communication," the BBC came to my school to interview a few students. My interview about my Asperger's syndrome didn't make it on the TV because they could only show about a minute of half-an-hour of footage, but there are a few separate shots of me, and even a close-up. You can watch it here: I appear between 0.45 and 0.48/9.

[Posted February 5, 2011]

Walt and a "Double Standard"

Last fall, I published a review of two new books about Disney animation. I closed the review by expressing regret that some of the more intriguing anecdotes about Walt Disney could never be explored in the prevailing climate, a climate dominated by what I called "The Approved Narrative." I cited an incident mentioned in Peter Bart's book Boffo! How I Learned to Love the Blockbuster and Fear the Bomb. Bart wrote:

The moguls (except for Darryl F. Zanuck) were Jewish guys whose manner and tastes were still tied to their Eastern European roots. Disney remained something of a hick from the Midwest who thought of Jews as accountants and merchants. I once made the mistake of asking Walt a question that had business implications (we were having lunch in the Disney commissary at the time) and he replied by saying, "Let me check that with my Jew." He started to summon a financial aide nearby, but I quickly changed the subject.

I heard recently from someone who had just stumbled across my review, and who asked that I not publish his or her name:

In your essay "The Approved Narrative," you quoted Peter Bart as quoting Walt Disney as allegedly having said, in some obscure context, "Let me check that with my Jew." Bart's implication, of course, was that Walt was anti-Semitic. The American public is continually bombarded with countless accusations of anti-Semitism, and I'm wondering if there is a term that means the same thing in reverse: when a Jew makes a negative or derisive comment about non-Jews. In my experience in Hollywood, that happens a lot.

Do you follow Floyd Norman's postings of cartoons on Facebook? On Thursday, he posted a cartoon of two people working at DreamWorks, making a mention of Jeffrey Katzenberg. In the various readers' comments, a guy named Tim Lewis, who claims to know Jeffrey quite well, said, "Jeffrey still calls me 'Tall Gentile Guy'!" Is that any more or less offensive than the comment that Bart ascribes to Walt? The terms that I more frequently hear from Jews are in the territory of "goyim schmucks," said in a tone of voice that leaves no doubt as to the hostile intent. Of course, I don't dare ever mention that—or even acknowledge that I noticed. The double standard is galling.

(I haven't seen Floyd Norman's cartoon, unfortunately. I've asked Floyd to be my Facebook "friend," but he hasn't responded. I can't really complain, since I have a boatload of "friend" requests that I haven't responded to, either. I'm still trying to warm up to Facebook, but it's hard.)

Let's first allow for the possibility that my correspondent is either unduly sensitive or prejudiced, perhaps in ways he or she may not realize. That leaves open the question of why Walt Disney has been singled out for accusations of anti-Semitism, when the evidence for such accusations has always been so slight and sometimes manufactured out of whole cloth (as when Neal Gabler, in his book An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, accuses Walt of refusing to hire Jews). The focus has always been on whether Walt was prejudiced, not on whether his accusers—many of them with Hollywood connections of some kind—were themselves acting from questionable motives.

And when did these accusations of anti-Semitism begin to surface? I can't recall running across any that originated when Walt was not only alive but was hiring Jews like Joe Grant and Maurice Rapf, seeking the counsel of Sam Goldwyn, receiving an award from B'nai B'rith, and choosing Richard Fleischer, the son of Max, to direct what was then his most expensive (and riskiest) live-action feature, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. The screenwriter Irving Brecher does write in his memoir The Wicked Wit of the West that when he worked for the Mickey Mouse Magazine in New York in 1935, he raised the question of Walt's supposed anti-Semitism with Hal Horne, the magazine's publisher; but Brecher cites no basis for his suspicions, and he says Horne rejected them. (Horne was Jewish, as was Kay Kamen, the licensing genius who succeeded Horne as the magazine's publisher. Both Horne and Kamen had long associations with Walt and Roy Disney.)

For the most part, the ugly rumors about Walt's anti-Semitism seem to have begun circulating after his death, when he wasn't around to refute them, along with idiocies of other kinds, like the urban legend that his body was frozen so he could be restored to life in the future. What could account for this irrepressible hostility and contempt?

One reason may be that some people have never been able to accept Walt's legitimacy as the head of an important Hollywood studio. (Comparisons with the wretched "birthers" who cannot accept Barack Obama's legitimacy as president may be relevant here.) The proprietors of the important studios have always been overwhelmingly Jewish; I believe that's true of all of them today, the Walt Disney Company very much included. Scarcely anyone except devoted film buffs remembers Darryl F. Zanuck—or, for that matter, the Jewish moguls who were his and Walt's contemporaries—but Walt Disney remains a major presence in Hollywood, his name of incomparable value; and he was, conspicuously, and I suspect in some eyes unforgivably, a Gentile in an industry that was for many years one of the few that welcomed bright and ambitious Jews.

If my correspondent is correct, resentment of Gentile interlopers still exists in Hollywood, extending not just to prominent figures like Walt Disney but also to people much lower in the pecking order. (Would Jeffrey Katzenberg bristle if one of his Gentile employees called him "short Hebrew guy"? The question answers itself.) This is of course a state of affairs that defies even the most civilized sort of discussion, given the hideous damage that anti-Semitism has inflicted over the centuries, culminating in the Holocaust. In that larger scheme of things, any superficial damage to Walt Disney's reputation simply isn't very important. But I can't help feeling that the persistent rumors about Walt are a symptom of a sickness, one that may be lamentably widespread in an industry that he ornamented.

From Will Hamblet: Somewhat in support of your question regarding Disney's supposed anti-Semitism is an article you published some time ago.

I believe you were quoting Walt's comments re Harry Cohn where he mentioned that his meetings with Cohn had been pleasant, but that he was quite aware that many of Harry's employees considered him a bastard. I think he then laughed and said that probably a lot of his own employees made the same remark about him.

Amusing anecdote containing nothing negative about Cohn's Jewish heritage.

MB replies: That anecdote appeared in Bob Thomas's biography of Harry Cohn, as reported by Jim Korkis in a May 14, 2009, post you can revisit at this link.

[Posted February 1, 2011]

From Gene Schiller: Disney may have bought into some of the typical Jewish stereotypes of the day, but that hardly amounts to anti-semitism. I’m sure he had equally opinionated views about other racial and religious minorities. Did this have a significant bearing on his hiring practices or his view of talent? I don’t see the evidence to support that.

[Posted February 9, 2011]

January 29, 2011:

Bookmarks

I've been immersed lately in work on my next book, about comic books, and this site has suffered as a result, but I don't want to miss the opportunity to recommend a few other books of exceptional interest.

David B. Levy, whose first two books about the practicalities of the animation life I've recommended in earlier posts, has written a third, Directing Animation. It has the same cheerful, sane, down-to-earth quality of the first two, but it also strikes me as the most satisfying of his books for the general reader (as opposed to people actually working in animation).

David B. Levy, whose first two books about the practicalities of the animation life I've recommended in earlier posts, has written a third, Directing Animation. It has the same cheerful, sane, down-to-earth quality of the first two, but it also strikes me as the most satisfying of his books for the general reader (as opposed to people actually working in animation).

Mark Mayerson, while acknowledging the book's many strengths, has faulted it for saying "very little about the actual craft of directing. ... The nuts and bolts of directing aren't here, let alone the distinction between what produces good and bad results." I can't disagree, but I still very much enjoy what amounts to Levy's portrait of the animation community in New York City. I'm not interested in becoming an animation director myself, and I feel reasonably well qualified to judge the merits of what winds up on the screen; but I don't know much about what goes on in contemporary New York animation studios, and Levy excels at depicting the day-to-day life in those places. He intends his book as a guide to the "people skills" a director needs, but for this lay reader, it's more appealing as a description of how people go about their work in a small, dynamic industry.

As in his earlier books, Levy makes New York animation seem like a much healthier environment than the fetid swamp on the West Coast. I don't doubt that it is—not a serene or hassle-free environment by any means, but also one not poisoned by the enormous budgets and monstrous egos that dominate Hollywood animation. Directing Animation has its rough edges—it feels more repetitive than the earlier books, and in general more hastily written—but its virtues certainly outweigh its flaws.

Didier Ghez has published the tenth volume in his series of collected interviews called Walt's People, and this installment is even more valuable than its predecessors, difficult as that might be to imagine. Volume Ten is devoted to interviews conducted by Bob Thomas, the Associated Press writer who was chosen by Walt Disney's family and Walt Disney Productions to write the authorized biography published in 1976.

Didier Ghez has published the tenth volume in his series of collected interviews called Walt's People, and this installment is even more valuable than its predecessors, difficult as that might be to imagine. Volume Ten is devoted to interviews conducted by Bob Thomas, the Associated Press writer who was chosen by Walt Disney's family and Walt Disney Productions to write the authorized biography published in 1976.

Thomas has written other Disney books over the years, most notably Walt Disney, The Art of Animation, the lavishly illustrated 1958 book that was for some of us who read it as young fans a magical portal into the history and techniques of Disney animation, like no book before it. The biography, while unmistakably "authorized" in its tone and emphases, is nevertheless remarkably thorough and accurate. And because Thomas started interviewing so early, and enjoyed the access that comes with "authorized" status, he talked to people who were rarely if ever interviewed otherwise, Ub Iwerks being just the most prominent example.

As with the earlier volumes, no one who claims to have a serious interest in Walt Disney and the history of his studio can be without this book.

Andrew Osmond, whose books on Satoshi Kon and Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away I've recommended in earlier posts, has written another book, a British Film Institute guide called 100 Animated Feature Films. It'll be published in the U.S. in April.

Andrew Osmond, whose books on Satoshi Kon and Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away I've recommended in earlier posts, has written another book, a British Film Institute guide called 100 Animated Feature Films. It'll be published in the U.S. in April.

This is, needless to say, a selective listing of animated features, and just in paging through this handsome book I'm intrigued by what has been included and what has been left out. Ralph Bakshi's Fritz the Cat is here, for instance, but Heavy Traffic, by general agreement Bakshi's best film, is absent. Likewise, there's no entry for Disney's Alice in Wonderland, but there are entries for two versions of the story that combine live action and stop motion. Walt Disney's Peter Pan and Lady and the Tramp don't make the cut, but latterday Disney's Hunchback of Notre Dame does, as does Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker and South Park: Bigger Longer and Uncut.

Such idiosyncratic choices, combined with my high opinion of Osmond's writings on Japanese animation, make me all the more eager to read the book.

From Eric Noble: I should definitely buy David Levy's books. I'll take about any advice I can get about surviving in the animation industry. From what I've seen, New York is going to be the place to learn animation. From what I've seen and heard, you can actually learn to animate there, as opposed to just learning storyboards and such in LA, where animation is farmed out to Asia. Who knows, maybe there are places I can learn to animate here in Seattle.

[Posted January 31, 2011]

January 18, 2011:

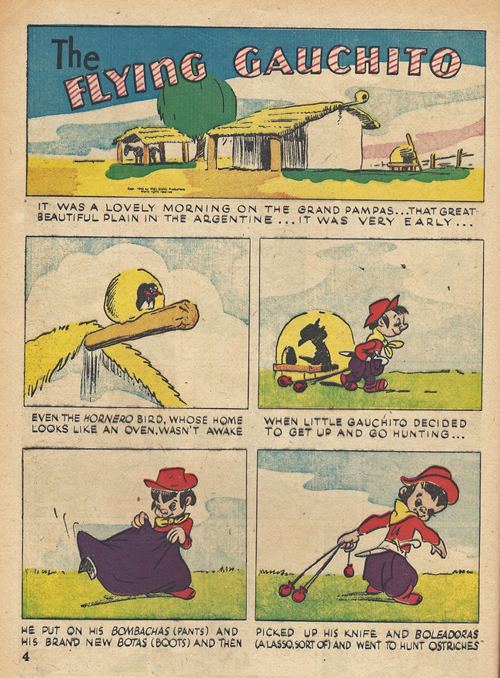

"The Flying Gauchito"

Last October, when I reviewed J. B. Kaufman's book South of the Border with Disney, I remarked in passing: "I'm tempted to make a big deal out of Kaufman's failure to mention the Joe Carioca story in Walt Disney's Comics & Stories for December 1942—the first original comics in that flagship title, for heaven's sake!—but I think it would be a little too obvious that my tongue was in my cheek." David Gerstein wrote to question that statement, suggesting that the first original comics in Walt Disney's Comics had in fact appeared in the September 1942 issue, in the form of an eight-page adaptation of "The Flying Gauchito." I replied to David as follows:

But (a) is that story really comics (no balloons, just captions), and (b) was it drawn for the comic book, or is it a reprint, or was it possibly slated for some other venue and used in WDC instead? According to Kaufman's book, "Flying Gauchito" was to be the Argentine segment of Saludos Amigos but was displaced by "El Gaucho Goofy" by early '42; presumably the version in WDC #24 was prepared when "Flying Gauchito" was still slated for Saludos. But where did it appear first?

That's still an open question, one which J. B. Kaufman was unable to answer when I asked it of him shortly after I got David's message. I'm posting the complete story, in the hope that someone among my readers will be able to say where it came from, if in fact its first appearance was not in Walt Disney's. Click here to go to the first page of the story and navigate to the rest.

"The Flying Gauchito" appears to have been drawn by Walt Kelly, perhaps in haste; it's a much rougher-looking piece of work than some of his other early stories for the comic books produced by Western Printing's New York office and published by Dell and K.K. Publications. If I'm right, and the story was drawn by early in 1942, it must have been some of Kelly's very first work for Western, possibly preceding even his debut issue of Fairy Tale Parade, which is much more polished-looking and was published by March 1942.

From Peter Hale: According to coa.inducks Walt Kelly only pencilled the strip, so maybe the crudeness of execution is down to an inexperienced (even non-Disney?) inker.

I can't find any examples of the "Flying Gauchito" storyboard, but I'm guessing that Kelly was using that as his source, because the story follows the film fairly closely, but without picking up on the final layouts and key poses which presumably evolved during production. (I presume that basing comics on the storyboard was a common practise, since the photostats would be a convenient reference—can you confirm or refute this uninformed assumption?)

In 1945 Kelly drew a 48-page comic book of The Three Caballeros, which I assume included "The Flying Gauchito," but I cannot find any images from within.

The "Flying Gauchito" story crops up again in Silly Symphonies No. 3 (1953). This more elaborately drawn version is by Fred Abranz, but comparing first pages (only!) it would seem he based his version on Kelly’s—the script has only minor alterations, and where Abranz has changed a panel’s contents (Gauchito getting up and dressing) the image reflects a better reading of the text but is unrelated to the film.

MB replies: Kelly's 1945 version of The Three Caballeros, Dell Four Color Comic No. 71, does indeed include "The Flying Gauchito," a nine-page version (with segues of a panel or two on the preceding and following pages) that does not resemble the very tentative 1942 version but is instead in Kelly's mature, if that's the word, antic style of the mid-1940s. The 1945 comic book's departures from Three Caballeros' continuity are frequent, and funny. Four Color No. 71 actually bears two copyright dates, 1944 and 1945, perhaps because Three Caballeros itself was released first in Mexico City in 1944.

I have no strong opinion as to whether Kelly only penciled the 1942 version, but it appears to me that whoever inked it did so in haste. Kelly did a lot of later comic-book work that looks just as rushed, if more assured.

Here's the first page of "The Flying Gauchito" from Four Color No. 71:

I can't get a decent scan of a page from the 1953 version of "The Flying Gauchito" without damaging the comic book, but it does indeed track the 1942 version very closely.

[Posted January 29, 2011]

January 12, 2011:

Glen Keane on Tangled

The justly esteemed Disney animator Glen Keane—who, it turns out, speaks French fluently—was in Paris last fall in connection with the opening there of the new Disney feature Tangled, as well as a show (just closed) of Keane's drawings at Galerie Arludik. He sat for a half-hour video interview with Basile Béguerie of the website CloneWeb. Happily for Anglophones, that interview has been translated into English by Christiaan Moleman, and is now available on CloneWeb's site along with the video of the interview itself, at this link.

The justly esteemed Disney animator Glen Keane—who, it turns out, speaks French fluently—was in Paris last fall in connection with the opening there of the new Disney feature Tangled, as well as a show (just closed) of Keane's drawings at Galerie Arludik. He sat for a half-hour video interview with Basile Béguerie of the website CloneWeb. Happily for Anglophones, that interview has been translated into English by Christiaan Moleman, and is now available on CloneWeb's site along with the video of the interview itself, at this link.

It's an excellent interview, which illuminates Keane's thoughts about CGI animation and his own work, as well as how Disney's computer-animated features are being made. Here's a representative passage:

I think about drawing as sculpture. I like the idea of sculpting a shape and when I draw the characters I put in the shadows, on a drawing of Beast or whoever... Ariel... and the other Disney animators ask me: Why do you do the shadows? That's crazy... No one's going to see it! We're going to paint it, clean it and it'll be lost.

But for me, the best moment of the creative process is the moment where I draw at my table, with the light... my desk is very dark, except for one light. I really immerse myself in the drawing.

That is the magic moment for me. Not necessarily the moment the film is projected on the big screen.

Thanks to Basile Béguerie for the link.

From Eric Noble: Very fascinating to read the thoughts of one of the respected people in animation. I think it's incredible how he approaches animation. I think learning sculpture could be very beneficial to animators, creating a character and its shape from the ground up. I believe I read somewhere Bill Tytla took sculpture classes when he was young. I'm sure that helped him later at the Disney studio. His characters always felt three-dimensional and as pliable as any living creature.

The part that intrigues me the most is when he describes the difference between Disney and Pixar. Pixar being the studio of "Wouldn't it be cool if?" seems somewhat apt, but then again, all fantasy could be construed as that. The line comes across to me as saying that all of Pixar's films seem to be fanboyish ideas being thrown into a pot and someone hoping it turns out well. I think that's another reason why animation is looked down upon. It's seen as a group of fanboys trying to emulate what their predecessors did, only with a few more bells and whistles.

[Posted January 13, 2011]

January 11, 2011:

Catching Up

§ THE STRETCHED FANTASIA: One of the hazards of running a site like this is that someone will discover an item months after it was posted and offer a cogent comment that gets lost because it was published so long after the original item. I've received several good comments like that recently, but let me recommend in particular Ralph Daniel's comment on the stretched Fantasia (with his improved scans of the article that prompted my post of November 17, 2009).

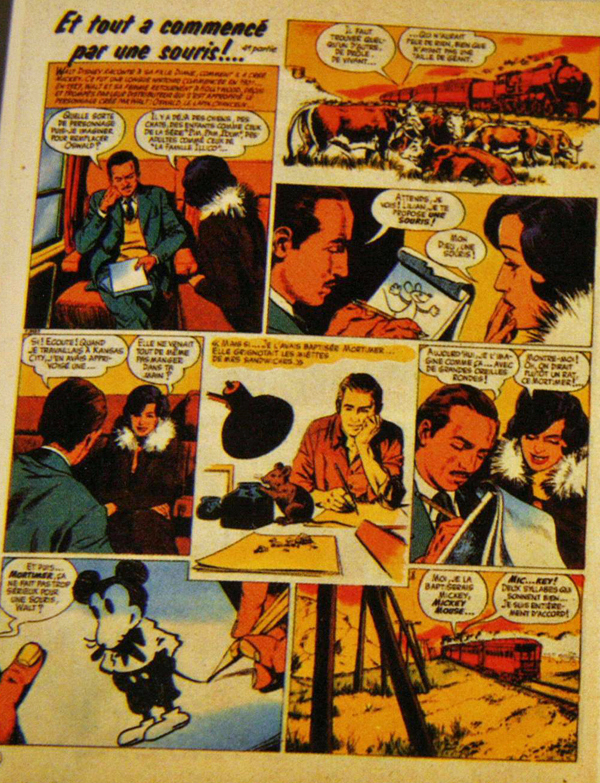

§ SACRE BLEU, LILLIE! And then there's the continuing mystery of "Fauntleroy Mouse," a mystery that I last explored in my post of July 7, 2010. Francis Lemelin, an animation student in Quebec, has sent me a photo of the appearance of this curious character in a French-language magazine called Beaux-Arts Hors Série. "There's a section on Disney comics, and with it a reprint of an old but undated comic strip on the creation of Mickey Mouse. The interesting thing is that it shows Walt Disney drawing Fauntleroy Mouse' (called here Mortimer) on his train back to Hollywood. It is then followed by Ub Iwerks telling him the problems of his drawing, while drawing Plane Crazy's Mickey Mouse on a new sheet. The whole story is told from Disney's view point, telling the story to a very young Diane Disney, and the comic is called—in French of course—Et tout a commencé par une souris!... 4e partie. [It all started with a mouse! ... Part Four] I wonder when this is from?" I wonder the same thing. [A lightning-fast update from Didier Ghez: "That story was written by my good friend Michel Mandry in 1979. It's based on Diane's story as told to Pete Martin. It was drawn by Carlo Marcello and first released in Le Journal de Mickey 1388 to 1391. The complete story is 8 pages long."]

Here's Francis's photo:

§ THE CLAMPETT ITCH: From Daniel Guenzel, a message that brought a broad smile to my face, and that I suspect will have the same effect on many of my readers:

If you will allow this observation (which your website writings helped to formulate), it has finally dawned on me, now that I am actually trying to learn this craft, why I am attracted to the work of Bob Clampett: after seeing his work (and that of his excellent animators) I feel inspired to do animation. I could never put my finger on the reason why I could watch and enjoy the cartoons of Chuck Jones, for example, but never get the itch afterwards to go to the light box and start drawing; whereas after watching a Clampett I couldn't wait to start sketching. His work has that effect while Mr. Jones's, however superb, doesn't. Of course the same feelings of inspiration come from watching Snow White or Lady and the Tramp or certain moments in Fantasia (particularly Mr. Tytla's devastating work), too, but that's a pretty high standard for an amateur to aspire to.

Absolutely right: anyone who lets himself respond to Clampett's cartoons without crippling preconceptions will find in them an energy and spontaneity like that in no one else's cartoons. I've written in Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age about how I think Bob got that unique quality onto the screen. To quote Bob, from an interview he did with Milt Gray for the book:

Absolutely right: anyone who lets himself respond to Clampett's cartoons without crippling preconceptions will find in them an energy and spontaneity like that in no one else's cartoons. I've written in Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age about how I think Bob got that unique quality onto the screen. To quote Bob, from an interview he did with Milt Gray for the book:

I put extra sheets of paper over the layouts and made little quick roughs. Sometimes I would sketch with a big, soft grease pencil. The scribbles and the dynamics of it...the paths of actions, and the anticipation and squashes and stretches, the changes in perspective and size, like a hand swinging up and past the camera. [Those sketches were sometimes] done right to the actual timing of what was going to happen, by moving a pencil across the paper; that suggests a path of action that a character is likely to take, especially if the character is moving at a high speed. You probably wouldn't think to give the character quite that path of action if you just started with a drawing, but when you run the pencil through it with just that feel, you do some things you wouldn't consciously think to do. [The sketches were like] the wave of a baton, if I were leading an orchestra—the waving of the pencil would give them the feel of the motion. It wasn't so much what the sketch looked like; it might be little paths, little bits of energy, as I was talking it. ... An extension of the energy of the character, the urge of the character, what he's feeling inside.

To read more, go to page 452 of Hollywood Cartoons.

§ BENZONOMICS: Bill Benzon has contributed any number of meaty essays and comments to this site—you can read his comment on my review of Tangled by clicking on this link—but to get the full Benzon treatment, you need to visit his blog New Savanna: Intimations of a New World. Bill writes there about a select cadre of animation creators—Disney (Fantasia, mostly), Miyazaki, Nina Paley. I'm sure no one else has given such close and admiring attention to Paley's remarkable feature Sita Sings the Blues. Bill doesn't write as a typical cartoon fan but as, to cite his self-description on his blog, "thinker, writer, musician, artist, photographer: pioneer," someone who gives films his full attention and writes about them in revealing detail. It is, in fact, this respectful attention to the films, and to the people who made them, that sets him apart from many academic writers whose work, rooted like Bill's in traditional literary criticism, might seem superficially similar.

§ DISNEY AT THE GILMORE: Back in 2007, I published an exhaustive account of the 1964 incident when Walt Disney wore a Goldwater campaign button to the White House ceremony at which he received the Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon Johnson. That piece included these sentences: "The Disney party's brief visit to Washington was actually an interlude in a trip otherwise dominated by lawn bowling. On the return trip, Walt and his companions stopped for several days (September 17-20) at Kalamazoo, Michigan, to visit with his friend Donald S. Gilmore, chairman of the board of Upjohn Pharmaceutical and a lawn bowler with Walt at Smoke Tree Ranch at Palm Springs. (The Disney-Upjohn ties were close then: Upjohn was one of the first corporate participants at Disneyland, and members of the Upjohn family had vacation homes at Smoke Tree, as did Walt and Gilmore.)"

§ DISNEY AT THE GILMORE: Back in 2007, I published an exhaustive account of the 1964 incident when Walt Disney wore a Goldwater campaign button to the White House ceremony at which he received the Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon Johnson. That piece included these sentences: "The Disney party's brief visit to Washington was actually an interlude in a trip otherwise dominated by lawn bowling. On the return trip, Walt and his companions stopped for several days (September 17-20) at Kalamazoo, Michigan, to visit with his friend Donald S. Gilmore, chairman of the board of Upjohn Pharmaceutical and a lawn bowler with Walt at Smoke Tree Ranch at Palm Springs. (The Disney-Upjohn ties were close then: Upjohn was one of the first corporate participants at Disneyland, and members of the Upjohn family had vacation homes at Smoke Tree, as did Walt and Gilmore.)"

The Disney-Gilmore ties continued after the deaths of both men, Walt's in 1966 and Donald Gilmore's in 1979. Gilmore began collecting antique automobiles in 1963, and in July 1966 he opened the Gilmore Car Museum at Hickory Corners, Michigan, near Kalamazoo and Battle Creek. One of the eight historic barns now on the museum property houses the museum store and an exhibit with a unique Disney connection, as the museum's website explains:

G Barn could easily have derived its name from the 1967 Walt Disney movie, the “Gnome-Mobile”, which featured a 1930 Rolls-Royce Sedanca Deville. Today, the car used in that film, starring Walter Brennan and Ed Wynn, is here on display next to the authentic movie set of the car's back seat.

After filming had ended Mr. Gilmore purchased the Rolls Royce directly from his friend Walt Disney, and as an added bonus Disney donated the original oversized movie set. This is an exact re-creation of the rear seat of the 1930 Rolls Royce which is actually almost four times larger than life.

That's the set in accompanying photo. The museum itself is clearly worth a visit if you're in the area, but especially if you're a Disney buff. The Gilmore is closed now for the winter, but will reopen May 1.

Jay A. Folis, the Gilmore's director of marketing, also sent me a scan of the photo of Walt below. This photo presumably wasn't taken at the Gilmore—I've seen prints offered for sale on the web—but, especially considering how much Walt appears to be enjoying himself, it would be interesting to know when and where it was taken.

From Gunnar Andreassen: The photo of WD and the children: I recalled where I had seen it: Remembering Walt, Favorite Memories of Walt Disney, by Amy Boothe Green and Howard E. Green, heavily illustrated with photos of WD. Unfortunately this book is very poor when it comes to information about the photos, and there is nothing mentioned about this photo, found on page 44. My guess is that is taken at Disneyland, but it probably could have been taken on a lot of places.

From Thad Komorowski: I enjoyed the flurry of items on your site today, particularly the Clampett piece. I can't say I agree with Dan Guenzel in that Clampett makes me want to draw/animate more than the other directors, but I do agree completely that an energy like no others exists. It's a very humanized sort of surreality. During a break from writing today, I screened my 16mm print of The Bashful Buzzard, and there is so much material in that thing that could easily be read as disgusting if it was handled with any less energy. The Scribner footage of the barnyard fowl's necks being snapped is pretty bold to put in there in the first place, but since it goes by so quickly and is animated so bombastically, it reads funny, which wouldn't have been possible had it been done "properly". Somebody needs to write a book called The Illusion of Life Sucks (that's not my bit of cleverness, but Steve Stefanelli's) with examples like this and the other Warner directors to bolster the point.

[Posted January 11, 2011]

From Eric Noble: So many interesting tidbits today. My favorite has to be the Clampett piece. Chuck Jones may be the cartoons that make me laugh the most, but Clampett's cartoons show the magic that only animation can ring. There is so much energy and vitality on them that I can see why it would make someone such as Daniel want to animate. Thank you also for posting that piece from your book. I find it fascinating to read how the directors went about their jobs. I always hope to find some inspiration in that. Hopefully more people will discover the genius of Bob Clampett's cartoons and see there is more than one meaning to The Illusion of Life.

[Posted January 12, 2011]

From Bill Benzon: Thanks for the nice blurb. As for just why I comment on so few titles, it's a function of my intellectual style. I want to know how things work, and that means paying close attention to what happens in a film. So I'll watch scenes and shots many times and go frame-by-frame in places. It's the only way to see what's going on. It also means that, alas, I only have time to do that for a few films. In the case of Sita Sings the Blues I have the additional incentive of having access to the artist, as Nina Paley lives in NYC.

It's clear to me that much very fundamental animation scholarship is taking place on the web. I'm thinking, for example, of the archival material that, say, Hans Perk posts, and of the mosaics that Mark Mayerson constructs, and so forth. This is fundamental and valuable.

FWIW, the single most popular page on my site is a post on "Sex, Power, and Purity in Kawajiri¹s Ninja Scroll." It's a very popular anime feature, more popular in the US than in Japan and, of course, I'm looking at two scenes where it deals with sex. My second most popular animation post is about the Pink Elephants on Parade sequence from Dumbo, while the third most popular post is about a one minute segment from Azumanga Daioh, a charming anime series that follows a group of girls through high school.

[Posted January 15, 2011]

From Chase Pritchard: I've been thinking about Daniel Guenzel's comment on Clampett's cartoons. It reminds me of why Dumbo fascinates me and will, I hope, continue to inspire me for years to come. You mentioned that fans like Clampett's cartoons because they "find in them an energy and spontaneity like that in no one else's cartoons." I can't help but think that Dumbo is like Clampett's cartoons, but it's almost like a different brand of spontaneity: "controlled spontaneity," meaning that the Disney artists were trying ideas that they would never dare to try again because that would upset the boss, and so they never went as far as the frenzied exhilaration Clampett frequently put into his later films. For example, if you look at the "Pink Elephants on Parade" sequence, you get that sense of exhilaration, but unlike Clampett's endeavors, it almost feels like the artists wanted to audience to enjoy the ride while it lasted and punch them while they're weak around the end. Clampett just announces what he's going to do, and because of that, you're just trying to catch your breath while watching his films (not saying that's a bad thing, just something I've noticed). You rarely see sequences quite like that in later movies, and it's a shame we'll never see such a idea being brought forth with such energy in years to come (Clampett keep that torch alive for a while, but alas, all good things don't last forever).

From Bill Benzon: A footnote, Mike. I just re-watched Porky in Wackyland and wondered

whether or not, in effect, THAT's where the Pink Elephants sequence came from. Did Disney's animators take that sequence as an opportunity to go WB, or even to go Clampett? Beyond the issues that I've addressed in my remarks on that sequence—it's dramatic role and internal logic—there's the simple fact that it's unlike anything else in the Disney repertoire of the time. I know some people see it as a parody of Fantasia, which makes SOME sense. But it makes even more sense to see it as an exercise in off-the-wall gags more characteristic of WB than Disney.MB replies: Since Bill sent me the message above, he has posted an extended analysis of Porky in Wackyland on his blog, at this link.

[Posted January 17, 2011]

January 7, 2011:

Tangled

You can read my thoughts about the latest Disney feature by clicking on this link.

From Eric Noble: Wonderful review. You've definitely got me intrigued and make me want to see the movie, but I'll wait to rent it on DVD. From what you're saying about this film, this could definitely be a step in the right direction for CGI. Whether or not the Disney artists will be allowed to pursue this further is something only time will tell.

BTW, when you talk about a dull literalness in in most CGI or later Disney films, what do you mean exactly. I'm trying to wrap my head around it so I can avoid it in my own work. What makes a true cartoon character or "cartoony" animation to you. I'm just trying to get a concrete definition, or yours at least.

MB replies: One example of the literal is rotoscoping: such tracings may be literally accurate representations of movement, but because there's none of what I've called selection and arrangement, what's significant and individual about that movement gets lost. I addressed this point many years ago in Funnyworld, when I wrote about Ralph Bakshi's Lord of the Rings, that ghastly festival of rotoscoping:

If The Lord of the Rings has served any purpose, it may have been to make clear just why rotoscoping is so unsatisfactory as an animator’s tool: it makes the indefinite definite, but in a random way.

We do not see people as line drawings; we see them as three-dimensional objects whose outlines may not be at all distinct, unless they are standing against a brightly lit background. Good drawings are necessarily abstractions, because they present human figures as arrangements of lines, and we do not see human beings that way. The lines may be arranged in many ways, to suggest the impression that our brains receive when we see a real person, or as a frankly two-dimensional pattern that has only a tenuous relationship with the ostensible subject. But in each case, the result is nothing like a tracing from a photograph. Such a tracing, even though superficially faithful to the outlines of the figure, is likely to leave out precisely what is most clearly visible to us when we see the figure itself—the contours and textures that can be recreated in line by a skilled draftsman.

Paradoxically, rotoscoped figures—with their crisp outlines—are disorienting and unpleasant in the same way that an out-of-focus film is: we keep straining to see what is missing, and we wind up with a headache. Bakshi’s approach to rotoscoping, using untrained artists and misdirected actors, simply guaranteed that the inevitably poor results would look even worse than necessary.

The clumsy efforts to reproduce real movement in CGI, through motion capture and otherwise, have failed for much the same reasons. It's misguided literalism of that sort that I don't see in Tangled, at least never to a disabling extent, and not at all in the horse Maximus.

[Posted January 8, 2011]

From Bill Benzon: enjoyed your Tangled review but, alas, I've not seen the film itself. If I'd known that the movement was so well executed I'd have gone to see it. Now I've got to wait for the DVD. I've done a bit of thinking about your remark that that bit of excellence seems to have been by accident, not design. You're right, but I want to get just a bit pedantic if you don't mind. What set me thinking is that animated films are made by a sprawling collection of people. What might have been accidental to a "boss" could have been quite deliberate by someone lower in the hierarchy. I'd think that the unnamed animators who got the movement right knew what they were doing. They may have lucked into the subtleties, but once they found them, they knew how to keep doing them time and again. And the "bosses" allowed them to do it—whether grudgingly or with enthusiasm I have no idea. But those bosses didn't plan a film that would be consistent with the believability of character movement. So, we've got design in one place, accident in another. The big question, of course, is: Now that Disney knows how to execute convincing movement, will they keep doing it and plan for it? I also liked your response to Eric Noble—who seems to be a perceptive young animator (he's commented on some of my New Savanna posts). This paragraph, in particular, was very shrewd:

We do not see people as line drawings; we see them as three-dimensional objects whose outlines may not be at all distinct, unless they are standing against a brightly lit background. Good drawings are necessarily abstractions, because they present human figures as arrangements of lines, and we do not see human beings that way. The lines may be arranged in many ways, to suggest the impression that our brains receive when we see a real person, or as a frankly two-dimensional pattern that has only a tenuous relationship with the ostensible subject. But in each case, the result is nothing like a tracing from a photograph. Such a tracing, even though superficially faithful to the outlines of the figure, is likely to leave out precisely what is most clearly visible to us when we see the figure itself—the contours and textures that can be recreated in line by a skilled draftsman.

If I commanded a university lab, some graduate students, and a budget, I’d set about investigating that. It feels right to me. Your suggestion implies that the crisp outline of a drawn figure may actually interfere with appropriate motion perception. Going back thirty years psychologists have been investigating how we perceive biological motion. The pioneer in this work is a Swedish psychologist named Gunnnar Johannson. He used an experiment technique that generated short film clips using pre-cursors to motion capture. Here’s how I described his work in a paper I co-authored with the late David Hays:

Gunnar Johansson's work on the perception of motion (1973, 1975) is suggestive. His basic technique has been to generate two-dimensional visual displays of dots in motion and ask his subjects what they see. One experiment involved images generated by moving people. Lights were attached to shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees and ankles; and then films were made. These films show patterns of movement among 12 spots of light against a dark background. Subjects had little difficulty identifying the nature of the images, often doing so in a tenth of a second (the time required to project two frames of film). In fact, subjects performed better on this task than they did with mathematically simpler images derived from simple deformations and rotations of elementary geometric figures.

The interesting thing about these clips is that you don’t see outlines of bodies or shaded images. If you’d examine a single frame all you’d see are dots. But when you see the dots move, the nature of the movement becomes obvious despite the fact that you don’t see bodies. The perception of movement seems to be independent of the perception of the object that’s moving. The job of a good animator is to provide very strong movement cues, and that’s going to be a bit tricky when the visual material is, as you say, so very different from a natural scene. I hope someone at each CGI studio has read your comment and taken it to heart.

MB replies: In regard to Bill's last sentence, as best I can tell from the web-traffic reports I check occasionally, very few people from animation studios ever visit my site. I don't think many of today's animation workers are much interested in the historical material that I particularly enjoy; and I don't think I say anything they want to hear when I write about contemporary films.

[Posted January 10, 2011]

From Brandon Pierce: Finally ready your review. I thought you were pretty kind to the film. And, I'm glad you didn't grasp at straws and gripe about Rapunzel never wearing shoes, like some other "official" critics did. One thing about Tangled that has bothered me is the design and look of the characters. They are so generic! Rapunzel, I swear looks like the same model for the lead female character in DreamWorks' Monsters vs. Aliens, and all they did was plop blonde hair on her. Couldn't they have come up with something more original or distinctive?

[Posted February 2, 2011]

January 6, 2011:

Flogging the Funnybooks

I'm still sorting through the piles of paper I brought back from New York and Washington late last year, but to share a little of what I found, I'm reproducing below a couple of ads from the American News Trade Journal.

The American News Company was for many years the country's largest distributor of periodicals to newsstands. Starting in 1917, it gave to newsdealers a (usually) monthly magazine to let them know what wonders were on the way from American's stable of publishers. Many of those publishers ran ads in the Trade Journal—the line between editorial and advertising copy was predictably fuzzy—and comic-book publishers were among the advertisers. Dell was American's most important comic-book client by far, although companies like Archie and Quality also distributed their comics through American.

Several full-page ads for Walt Disney's Comics & Stories appeared in the Journal in the '40s, when that comic book's circulation was growing rapidly. Although it bore the Dell label from 1948 on, Walt Disney's was never actually published by Dell, but was published instead by Western Printing & Lithographing Co., using the name K.K. Publications; the ads for Walt Disney's accordingly mention only K.K.

By the time the ads appeared, though, Western Printing was producing not just Walt Disney's Comics but also all of the comic books published under Dell's name. Companies like Disney made their licensing agreements with Western, not Dell, but it was Dell that handled the distribution of the comic books through American News. Western is never mentioned in trade publications like the Journal.

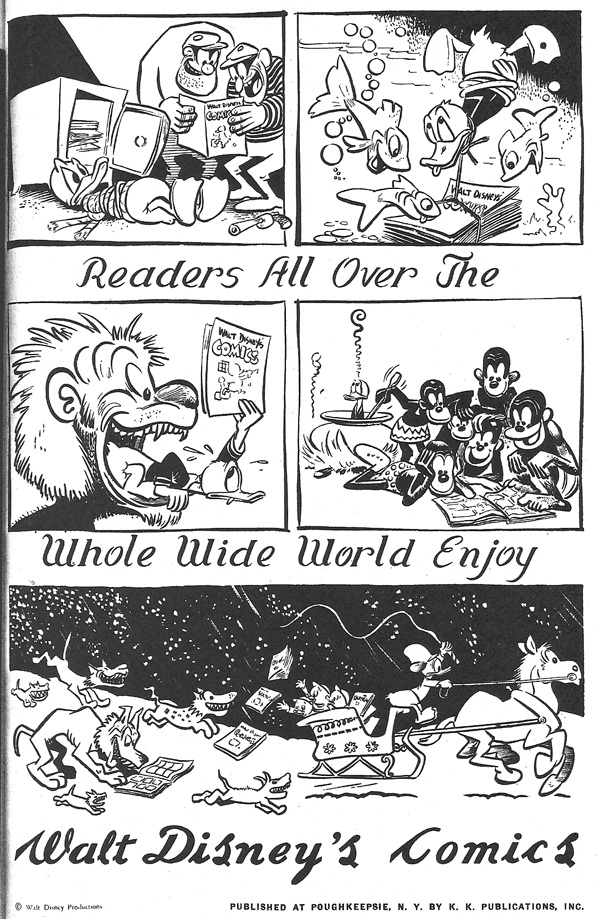

Of K.K. Publications' ads for Walt Disney's Comics, easily the oddest is the one below, from the August 1946 issue:

It's by Walt Kelly, who was in 1946 the best and probably the most prolific of the cartoonists free-lancing for Western Printing's New York office, under the great editor Oskar Lebeck. The ad has the manic flavor of some of the Dell comic books Kelly authored around that time, either solo or in collaboration, like the Pinocchio and Oswald the Rabbit one-shots published in the Four Color series in 1945-46.

The ad's message is strange when you think about it: Walt Disney's Comics has such strong appeal to evildoers that it distracts them from their nefarious deeds. A message better suited for a Charles Biro title like Crime Does Not Pay, one might think. And then there's the top right panel, in which Donald Duck is apparently the target of a gangland execution, and it's not his would-be killers but stray fish who delight in the comic book. Funny stuff, but still...

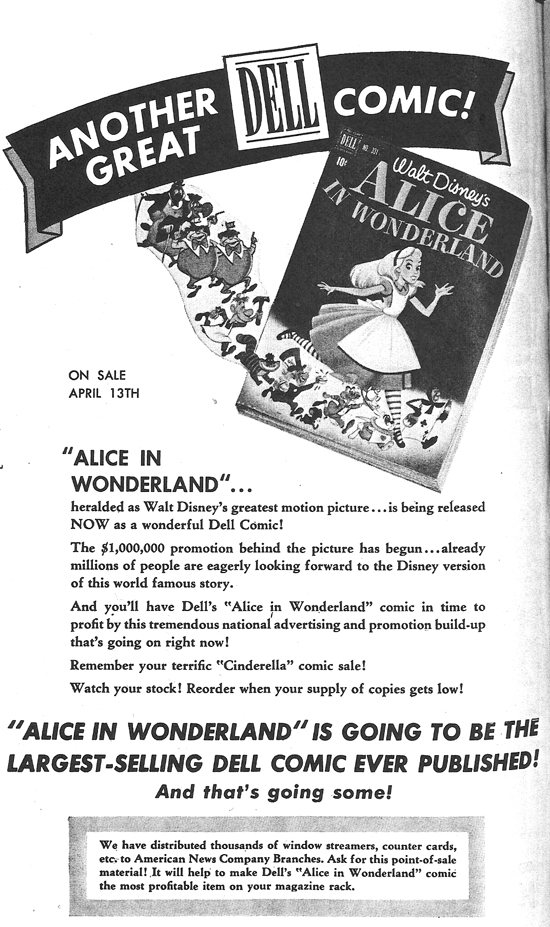

More conventional but intriguing in its own way is this Dell ad from the American News Trade Journal for May 1951:

I remember the first time I saw that comic book, presumably in April 1951, when I was visiting at someone's home. To see it but not to own it—oh, the torment! The book's cheerful wraparound cover still makes me smile, but the insides are an ungainly cut-and-paste job in which stiff panels copied from publicity stills alternate with drawings distorted with an ugly vehemence. I can't guess what Western Printing's editors were thinking when they made that assignment. (The cartoonist involved drew other Dell comics around that time, but I don't have a name.)

Dell's Alice in Wonderland was, however, unquestionably a big deal in comic-book terms, as evidenced by more than just the Journal ad, with its remarkable invitation to "reorder when your supply of copies gets low." The Alice comic book was not simply a commercial tie-in but was also an important element in promotion for the film—it was published almost three and a half months before Alice in Wonderland's theatrical release.

Western Printing paid Disney royalties on 3,008,288 copies of the comic book. That was almost certainly the number printed, rather than the number sold, but the latter figure would still be impressive even if, as is likely, it was hundreds of thousands lower. (Western paid royalties on 2,757,043 copies of the Cinderella comic book cited in the ad; it was published late in 1949.)

One measure of the Alice comic book's importance in Western's scheme of things: it's a 52-page comic book (counting covers), published at a time when all other such Dell one-shots had been driven down to 36 pages, thanks to the inflation spawned by the Korean War. In the spring of 1951, only Dell's monthly titles, which were supported by mail subscriptions as well as newsstand sales, were still at 52 pages, and they all shrank to 36 pages before the end of the year.

Alice in Wonderland disappointed at the box office, but apparently the comic book's results were strong enough to encourage Western and Dell to push ahead when Peter Pan's release was imminent, late in 1952. Dell published not just an adaptation of the film—drawn by Al Hubbard, who was much better suited to the task than the Alice artist—but also a separate one-shot devoted to Peter and Captain Hook, and, most remarkably, a 208-page (plus covers) Peter Pan Treasure Chest that sold for fifty cents. That was an intimidating price for a comic book in 1952, I can testify from personal experience.

From Merlin Haas: According to Alberto Becattini's indexes, the Alice in Wonderland story in FC #331 was penciled by Riley Thompson and inked by Bob Grant. Cover was by Bob Grant. Story by Del Connell. There's also another Alice Four Color, dated two months later (July): Unbirthday Party with Alice in Wonderland #341. This one's only 36 pages, with story by Don Christensen and art by Al Hubbard. I haven't looked at either in a long time, but I would imagine the Hubbard one is reasonably entertaining.

MB replies: I should have mentioned the Unbirthday Party one-shot, which was indeed drawn by Al Hubbard. A nice-looking comic book, like all of Hubbard's, but definitely targeted at very young children, with puzzles and games interspersed in a very simple story.

From Don Benson: Back in those pre-video days, comic book adaptations were pretty darn big—along with punchout books, coloring/sticker books, and those Whitman not-real-enough-for-a-book-report editions with color hardcovers and spot-colored illustrations. I was born in '55, but by the time I was literate they were still a ritual.

The adaptations weren't just graphically loose. The comic Dumbo" replaced the movie's closing "success" montage with scenes showing the little circus was now rich and modern— even Casey Junior had been rebuilt into a smirking diesel engine. The Three Caballeros, drawn and presumably written by Walt Kelly, tossed in new characters and gags (the popup-book train acquires a chatty engineer who'd be at home in Pogo).

The Sunday comic strip was another story, at least in my era. It ran towards sketchy drawings and skimpy writing, often with a hasty wrapup—like they abruptly realized they had to start the next movie. This was frustrating for kids who scoured the available media for samples of the next Disney (usually heralded by a brief trailer right after the credits on the World of Color). In retrospect, maybe that was the idea.

One little irony is that modern comic adaptations seem to be infinitely slicker, insanely detailed and often precise recreations—now that we have ready access to the films themselves and would prefer the comics showed us something different. I'm not counting the pricy "continuing adventures" comic books.

I especially miss the punchout books. Without scissors or glue, you could assemble vehicles, houses, and other fairly neat stuff, like the toy making machine from Babes in Toyland. Last time I noticed one, years ago, it was called a "press-out book" and offered little more than some standup figures and maybe a backdrop.

[Posted January 7, 2011]

From Eric Noble: I own the Alice in Wonderland comic book, or at least the reprint from Dell's Junior Treasury in 1955. I've posted the pages on my blog here. Anyway, Riley Thompson was not meant to draw more realistically drawn characters like Alice. I do get the feeling that he tried to trace some of the animators drawings, badly. It's interesting enough as a comic book, but it doesn't grab me like the film does.

[Posted January 8, 2011]

From Matt Crandall: It was interesting to read your article about the Alice adaptation, and the comments that identify the cover artist and inker as Bob Grant. I always thought the cover and interior didn't match. Interesting to note that Bob Grant was the artist on a difficult to find Alice coloring book which I blogged about, including five pages of original art. Bob Grant definitely had his own treatment of Alice, which is particularly noticeable in her eyes.

[Posted January 29, 2011]