"What's New" Archives: August 2011

August 30, 2011:

August 21, 2011:

August 18, 2011:

August 11, 2011:

August 8, 2011:

August 30, 2011:

Innocence Is Bliss?

Kevin Hogan writes:

I enjoy reading your website and referencing your book. In general, I feel that you are a keen observer and that you are generally correct in your criticisms of films and art work. I feel that sometimes you focus too heavily on details and thus “miss out” on the enjoyment of the overall film. That is possibly only a perception of mine, but the more I read your work the more convinced of your “lack of innocence” in watching and enjoying a film I become.

I do feel, however, that if my perception is true I am beginning to understand your perspective. I was watching the Chip n’ Dale cartoon Two Chips and a Miss recently (a favorite of mine from childhood) and I found myself enjoying it much less than I did when I was a child watching the Disney Channel.

After some reflection, I came to realize that I enjoyed the cartoon less because I know much more about animation now after study/ research/ reading than I once did. I now see the Clarice “showgirl” sequence as a pale imitation of Red Hot Riding Hood and the dueling music section that followed as “Freleng-esque” (and not as good, in my opinion, as some of the better Merry Melodies in developing music based gags). I find myself having a tougher time enjoying the films as entertainment now that I have a broader scope of knowledge.

This is a very long way of asking if you find your joy in animation diminishing as your knowledge grows… I appreciate hearing your response.

I don't think my pleasure in animation has been diminished by my decades of study of cartoons of all kinds. Two friends and I watched the new Blu-ray of The Incredibles the other day, and I enjoyed that film at least as much as I enjoyed it the first, second, and third times I saw it (and I enjoyed it a lot, as my review shows). I constantly find myself surprised and delighted by cartoons I thought I already knew well. I remember watching all the earliest color Mickey Mouse cartoons in chronological order a couple of years ago, for the benefit of a friend's grandson (who promptly got bored and went wandering off to make loud noises), and marveling at how good those cartoons were, and at how miraculous it was that one wonderful cartoon succeeded another, with no significant lapses in quality. Blu-ray can lift a veil even from cartoons that I've seen multiple times in a theater. Watching the beautifully restored Blu-ray of Fantasia, with a decent sound system, I fully understood for the first time just how strong an impact that film could have made on its first viewers, back in 1940. Knowing a great deal about how Fantasia was made, and having known dozens of the people who worked on it, didn't diminish my pleasure in the least, but, if anything, added to it.

But what Kevin is saying, I suspect, is that such pleasure, however great it may be, is hopelessly compromised by what he calls a "lack of innocence"—a lack to which I cheerfully plead guilty, although if I were totally innocence-free I would be working harder to suppress other people's awareness of my many eccentric habits: watching cartoons, reading comic books, riding the bus downtown to the library, walking as many places as possible, and so on. There are a lot of fans, of whom Kevin may or may not be one, who think that the only valid response to a cartoon is the response they felt when they first watched it as a child. I think these tend to be the same people whose dietary habits are locked into those of a ten-year-old, so that they resist eating anything but hamburgers, hot dogs, milkshakes, and the like. No sushi for them! And let's not even talk about rabid sports fans, than whom there's no one more infantile, or people who listen only to the pop music they heard as teenagers, or...

But what Kevin is saying, I suspect, is that such pleasure, however great it may be, is hopelessly compromised by what he calls a "lack of innocence"—a lack to which I cheerfully plead guilty, although if I were totally innocence-free I would be working harder to suppress other people's awareness of my many eccentric habits: watching cartoons, reading comic books, riding the bus downtown to the library, walking as many places as possible, and so on. There are a lot of fans, of whom Kevin may or may not be one, who think that the only valid response to a cartoon is the response they felt when they first watched it as a child. I think these tend to be the same people whose dietary habits are locked into those of a ten-year-old, so that they resist eating anything but hamburgers, hot dogs, milkshakes, and the like. No sushi for them! And let's not even talk about rabid sports fans, than whom there's no one more infantile, or people who listen only to the pop music they heard as teenagers, or...

I can certainly remember my "innocent" responses to various cartoons and other kinds of films. One of my most vivid memories is of seeing my first Three Stooges short, I think on the same bill with Disney's Make Mine Music (which didn't make nearly as strong an impression). I was six or seven, and sitting in the balcony. When I saw the Stooges short, I was in heaven: I had no idea that such fabulous movies existed. Why, the Stooges did everything to one another than I never dared do to my little brother! I don't remember the title of that Stooges short, but I do remember seeing other Stooges shorts soon after that, and regarding them with the same sort of rapt admiration. I've seen many Stooges shorts in the years since I became an adult, and I still feel a limited affection for them, but on the rare occasions when I've watched two or three in a row, I've gotten very tired of them, very quickly. Does that mean I suffer from a "lack of innocence"? Or does it means my taste has improved with age and broader knowledge? Both, I'm sure.

A loss of innocence, in Kevin's sense, is inevitable, and trying to sustain such innocence through artificial means (as by savaging people who refuse to swoon over whatever happened to be the object of one's childhood enthusiasm) can yield only sickly results. You can confirm that by visiting any number of animation-related websites. There's always the risk, if you accept that loss of innocence, that you'll eventually decide that animation is not the most important thing in your life, and that greater rewards can be found elsewhere. But surely that's a risk anyone who claims to be a grownup should be willing to take.

For the record, I think Kevin's current opinion of Two Chips and a Miss is correct. A clunker, for the reasons he cites, among many others.

From Thad Komorowski: Recently, I had the pleasure (?) of seeing a truncated copy of the Columbia Phantasy cartoon Wacky Quacky, directed by Alex Lovy, for the first time. It was missing at least a half-minute of footage, but it was still coherent, or at least coherent as a 1947 Screen Gems cartoon can be. The story idea is nothing short of inspired, for my tastes anyway: what if Daffy Duck just grabbed the hunter's gun and started shooting and chasing him to avenge his fellow ducks? That's the story of this cartoon, and my mention of Daffy isn't ironic—the duck here IS Daffy Duck. The design is exactly the same, as is the voice, sans lisp (Stan Freberg, possibly). Even some of the animation is reminiscent of the Warners duck. I suspect Bob Clampett's presence at the studio had a lot to do with this, as a cat that strongly resembles Sylvester shows up in three other cartoons that same season.

It was a thrill to see 1940s animation I hadn't seen before, especially from that LSD-laden studio and because of the clear case of plagiarism. There was a particularly inspired gag where the hunter runs through a short, hollow log, taking about eight seconds to do it. The duck runs through it in about a second, what we expected the first time, and comes back to comment, "Shortcut!" Unfortunately, though, I have to share David Gerstein's "editorial" opinion that the majority of it is just stuff going on with no sense of structure, like most Columbia cartoons. Darrell Calker was the real star of these intriguing misfires with his spidery music scores.

This relates to your latest post, not just because the cartoon came from the same studio as those wonderful Three Stooges films, but because of my initial reaction of excitement turning into one of dissection and disappointment. It's generally true, people are inclined to continue to embrace what they liked when they first saw it (usually as children). Nostalgia is too often used as smokescreen for having no taste as an adult, and the word gets thrown into discussions to somewhat tacitly acknowledge that whatever is being spoken about's artistic merit is suspect. But often when it's called into question for why they still hold it dear even when they know that is so, and I find this true for animation people more than any other, they become exceedingly hostile. (I'm reminded of that commenter on Cartoon Brew who was enraged that you felt her tears shed during the opening of Up weren't genuine.)

But I think the nature of discerning taste can be continuously fluctuating. I was once, for an example of the opposite scenario, fairly critical of Preston Sturges a few years ago when I started an active interest in classic film. I originally found his movies wholly superficial, whereas upon revisiting them, I've seriously enjoyed them for for the illusory aura they cast and the truly brilliant screenplays. I'm wondering why the hell I ever thought what I did to begin with.

True, I'm young and stupid and probably have much more radical turns in my tastes ahead. But even in later years this can happen, when one's viewpoints are supposedly firm. I recall that you were quite impressed with the original Toy Story, for example, though later you dismissed it as "dross" with the other Pixar movies. Not calling you out, for I too (as you well know) had a similar grim epiphany with Pixar, but it's still evidence that time can be just as much of a factor in taste development, maybe even more so than "loss of innocence."

MB replies: I've never seen Wacky Quacky, I'm sorry to say. It was one of a handful of Columbia color cartoons that eluded me when I was writing Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, even though I had the expert help of Mark Kausler and other rare-cartoon sleuths.

Sturges is an interesting case. I've seen The Lady Eve perhaps a half dozen times, and my opinion of it changes each time I see it. The last time, the sheer absurdity of its premise got to me. I'll probably feel differently the next time. But that's OK: our opinions should change as we grow older and learn more, and with luck those opinions will be not just different but also more thoughtful and nuanced and insightful.

As for Toy Story: "dross" may be too harsh, but I think most subsequent Pixar films have been increasingly shallow and false and even cynical (Cars 2, anyone?), and it's difficult not to read their faults back into earlier and superficially more attractive films.

While I think of it: Kevin Hogan has also written to me about Miyazaki's films, and I've posted his comment on that too-long-dormant Feedback page.

From Nicholas Pozega: To that Kevin guy, I’m sure I feel like that sometimes, but that’s probably because I either expect too much, or look for something that ain’t there. I don’t usually suffer from that unless I’m thinking too much about a film. I can enjoy watching a 30’s cartoon as much as a 40’s cartoon, even if its for different reasons.

That said, opening up to how diverse the world of animation is can really dilute the value of something you grew up with. I remember when I was a kid that I had this Disney Christmas VHS tape, with Pluto’s Christmas Tree, Donald’s Snow Fight, and “Once Upon A Wintertime” (excerpted from Melody Time). I still like those shorts to this day, but I feel the reason I appreciated them was because it was the only thing around I had to watch. I rarely saw classic Disney shorts on TV, and mostly grew up on both old and new Disney features. I think this limited selection made me appreciate them more than, say, seeing all of the 400+ Disney shorts brought together in chronological order on the Walt Disney Treasures DVD sets. Once you see all of the shorts side by side, especially when compared to shorts from other studios of the time, it really tends to dilute the value of individual shorts in the vast ocean of animation, unless you have specific standards and dogmas established as to what you consider “quality” animation.

Also, I actually used to have a VHS recording of Two Chips and a Miss. I remember it as an amusing cartoon, although I never once thought of it has Disney’s take on Red Hot Riding Hood—the theme similarities are general at best, no more similar than a late 40’s Daffy Duck short is to a typical Donald Duck short.

From Milton Gray: I really enjoyed reading your article, "Innocence Is Bliss?"! I felt that you were giving all of us an insight into your own soul, as well as articulating for many of us how we ourselves feel about maturing as cartoon fans. It can be difficult to put feelings into coherent thoughts, and then express those thoughts in words. It's great when we can find something written by another person that we can point to that articulates our own feelings.

From Kevin Hogan: Thank you, Michael, for your thoughts. I greatly appreciate the time and effort you took in responding thoughtfully. It is rare to given that sort of respect.

No, I am not one of those people who believes “that the only valid response to a cartoon is the response they felt when they first watched it as a child.” I am often accused of trying to give validation to a cartoon as a serious form of art (“Isn’t that just for kids”- sigh- Guilty as charged). I feel that cartoons should be given the same respect and critical thought that live action films receive (… I’m preaching to the choir…)

I am genuinely glad to hear that you are able to find the balance between growing your mature tastes and still finding joy/ entertainment in the films. Maybe there is hope for me yet! I’d like to see more of that joy in your writing (stop short of being Leonard Maltin, though).

I do, however, feel that a voice should be given to those “people whose dietary habits are locked into those of a ten-year-old”. I may not be one of them, but I must admit that I am at times somewhat envious of their take. A friend of mine (a casual, yet still passionate cartoon fan) read your comments on my post today, and he told me that although he does not really know what we are talking about he still enjoys that cartoon (Two Chips and a Miss).

Is my friend a “locked-in 10 year old” or is he responding to the films the way the filmmaker intended? Who cares about "Red Hot” or “Friz Freleng”? The cartoon isn’t genius, but it has a cute little premise. I’m sure that Jack Hannah (I believe the director…) was trying to make an entertaining film, and was not checking himself or his staff for originality. The cartoon is a lot like the recent Pixar films—somewhat shallow, derivative, lacking in inventiveness. But if you are not a serious researcher/ film student, you don’t care. And I feel that while such a view is somewhat simple and uneducated, it still has weight and meaning. If a work of art is good, you should not feel obligated to find out if something else is better.

Again, I like to delve deeper with you. But to those who think Mater and Lightning McQueen are funny: Sometimes your joy means more than my critique.

From Don Benson: For me it's the less ambitious (and less successful) films that offer the

most pleasurable repeat viewings. You usually recognize their weaknesses from the get-go, and it's no shock to spot the manipulation, narrative duct tape, or budget shortcuts.

You can go back and appreciate the artistry of a great film, but you can now see the mechanics of that artistry. You focus on things that were intended to slip by almost subconsciously, like stretch and squash. Moments that were intensely moving on first encounter become admirable displays of acting and staging. Yes, the tableau of Jock howling over his fallen buddy in Lady and the Tramp still gets me. But now there's an awareness (and a little resentment?) at how all the gears are turning to wring out that reaction.

It's like revisiting Buster Keaton and being very aware of an amazing stunt, or a cunning setup, and missing the gag it was meant to serve.

Footnote: I thought Two Chips and a Miss was a perfectly decent Chip & Dale, with the same modest pleasures as their persecutions of Donald or Pluto. What was strange was that they never before and never again took C&D shorts into the familiar "small animals living like people" milieu. Was this a conscious experiment? If so, what decided them never to revisit it?MB replies: Of course you're going to spot the "mechanics of that artistry" on closer study of a great film, or any great work of art. That's the difference between art and life: you have the "mechanics of artistry" in the artistic depiction of a tragic death, but when you have a tragic death in real life, you don't have the mechanics, you just have the death. But what you also have in a great work of art, or at least a lot of them, is a profound connection between what's merely represented and the real thing. Understanding a little of how that connection has been established can't diminish my pleasure in what I'm seeing or reading or hearing.

To take a relatively low-level example: do my wife and I start sniffling during Puccini's La Bohème—and we always do—because we think that poor girl on the stage is actually dying? Or do we have to fight off tears because what we see and hear gives audible and visual coherence to what are ordinarily fragmentary and distracted thoughts and emotions? The latter, of course. We see and hear on the stage what we know, but too easily overlook. With a greater opera, or greater works of other kinds, the connection is deeper, and my response less immediate but I think more meaningful.

Trusty's "death" in Lady is, like Baloo's "death" in Jungle Book, too crudely manipulative, the mechanics all too clearly visible, for me to feel anything when it happens. I find Snow White's apparent death far more affecting—even after countless viewings—because Walt and his people took such pains to make the dwarfs' feelings for the girl seem real. They grieve for her with the grief of real people, not the histrionics of ham actors. Walt wanted that connection, and it's there.

On Two Chips and Miss: it's fine with me if people who like it continue to like it. I am, after all, that old man down the street who reads funnybooks. Who am I to say? But I likewise insist on my right to say that Two Chips is, when measured against the standards set by the best Hollywood cartoons of the same general kind, not very good. Just for the heck of it, here are some of the notes I made when I watched a 35mm print at the Library of Congress back in 1978:

The animation of the chips is ordinary and even stiff, lacking the quickness and charm of the chips in the cartoons in which [Bob] Carlson is credited as an animator.

The chips' rivalry at Clarice's door—as they steal flowers, put a hose up through flowers, substitute mothballs for candy, and finally come to blows—is very clumsily handled, with no psychological precision whatever. A good example of all-thumbs animation.

The nightclub scene with Clarice singing—the chips whistle and pound the table, Dale absent-mindedly eats a glass, Chip bounces from table to table on his butt—is shamelessly lifted from Avery, although it lacks utterly Avery's extravagance and wit. The chips even become drooling wolves. The resemblance is heightened by Clarice's highly feminine (full-hipped) figure.

The ending is sappy: the chips' rivalry is not resolved, but rather ignored, as they accompany Clarice in "Little boy/girl."

The nightclub appears to be empty except for the three chips.

I guess my question would be, for this cartoon's fans, "By the way, have you ever seen Little Rural Riding Hood"?

[Posted August 31, 2011]

From Kevin Hogan: Agreed on Rural Riding Hood. I didn’t think of that before—the cartoons have interesting parallels in plot. I agree with your criticisms on the cartoon as well—the lack of resolution to the rivalry is especially galling. I find your understanding of “ten year old” opinions to be enlightened as well.

I do think that it would have been best for Hannah/ Disney not to cast popular characters in Two Chips—Avery’s casting of characters with little or no weight/ depth allows him to torture his characters unmercifully for full comic effect… If Avery did Two Chips he would have had much more outrageous gags when the two are fighting in the girl’s doorway—bombs, fire, slamming of the door in one’s face, etc. Chip and Dale cannot go to such extremes due to the “weight of reality” in their characters.

As for Mr. Pozega—I appreciate your comments, but I disagree with your late '40s Daffy/ Donald comparison. The “Showgirl” sequence in Two Chips is so desperate to be “Red Hot” as to be sickening. The characters' faces literally turn into wolves at one point! Donald in the late 40s became domesticated and a foil for other characters (namely Chip and Dale in some of Donald’s worst cartoons in my opinion). Daffy was evolving into Chuck Jones’ “greedy” and “spotlight hogging” character. Some similarities exist, but their overall effect is quite different in how the director’s handled them.

As for Mr. Benson—I agree with your point on the strangeness of Hannah suddenly casting two “natural” characters suddenly into a humanized role. I always found that weird as well. I have to agree with Michael, though, on Lady and The Tramp. I find the scene to be emotionally manipulative.

From Thad Komorowski: I had the same reaction to The Lady Eve as you did: too unbelievable for its own good. But I still marveled at the power its leads have to make anything they do interesting (especially the hideously underrated Charles Coburn). Even bearing that in mind, Howard Hawks's Ball of Fire is in every way a superior take on the "Stanwyck as a charlatan" theme.

I really got a kick out of seeing your LoC notes for Two Chips and a Miss. It provides great insight into your critiquing process, one that's more learned and organized than other historians, I'd dare say. I'd pay for some kind of "guide" with all of these notes, just for leisure reading. I really laughed at the mention of the lack of Bob Carlson accounting for the stiffness. I can't muster up a lot of enthusiasm up for Jack Hannah, but I appreciate those chipmunk pictures more after seeing the real-live things running around in Ithaca; they really nailed those critters' movements and caricatured them funny! It's not present in Miss, though. Hey, post that Carlson interview!

MB replies: Agreed on Charles Coburn, and on the casts of Sturges's films in general. Wonderful (and well-directed) actors can make even a dubious story a great deal of fun to watch.

I'd love to post the Carlson interview(s), among others, but unfortunately, my assistants Miguel, Michel, and Mikhail are lazy duffers who leave me to do much more work than I have time for.

[Posted September 2, 2011]

From Vincent Alexander: I've really enjoyed reading your post Innocence is Bliss, as well as the comments inspired by it. Like Nicholas Pozega, I also grew up with a VHS that included Pluto's Christmas Tree and Donald's Snow Fight. I watched the tape every year around Christmas time, and those two cartoons always excited me and put me in the Christmas mood. Seeing them now, its clear that both are decent but unspectacular Disney shorts, not much different than other cartoons made in their respective eras. I have a nostalgic enjoyment of them, but I wouldn't defend either of them as classics. For another example: as a kid, I remember constantly watching lots of Disney animated features, as well as Don Bluth's Anastasia, all with a similar level of enjoyment. However, over the years, my tolerance for the Bluth film has diminished, whereas I've gained admiration for the Disney movies. My "lack of innocence" may have caused me to acknowledge the awkward animation and erratic storyline of Anastasia, but I enjoy Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Pinocchio more than I ever did, so I can't cite it as a bad thing.

Still, it is possible to lose too much innocence. After all, many people "outgrow" animation altogether. They probably think it's because they are growing more sophisticated, but they're really just denying themselves the immense pleasures of the Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons. Then again, I suppose there's a difference in pretending to be sophisticated (and thus refusing to see artistic brilliance in films that aren't considered "adult"), and actually being sophisticated (and therefore having different reactions to films based on how much you've learned about the medium).

And one more thing—I liked seeing the focus on Two Chips and a Miss, not because it is a particular favorite of mine, but because I'm always interested in seeing critical analysis of golden age cartoons that are generally ignored. I've read all sorts of treatises on classic shorts like Duck Amuck and The Great Piggy Bank Robbery, as well as infamous failures like The Golden Touch, but I don't think I've ever seen any discussion of, say, Friz Freleng's My Little Buckaroo or Arthur Davis's Bone Sweet Bone. Its nice to see some attention given to shorts that have been routinely ignored, even if they aren't actually all that good.

[Posted September 4, 2011]

From Kirk Nachman: I read your thoughts about innocence, and cartoons, and critical maturity, and I ask myself, how does Mr. Barrier arrive at his critical positions. Comparison, the setting of one qualitatively against the other, seems heavily put to use, with the preferred object established as such with nothing more than a subjective assertion, or favored precedent. This together with the impressionistic art-review style of journalism, where the critic describes his reactions to whatever subject matter or material he's confronted with, bereft of any greater defining critical edifice than his own impressions, moods, circumstantial awareness. Yet what could be more elusive to the bluff of critical assertions than humor, (something which left Aristotle's corpus incomplete) and what more basic element to animated cartoons than humor, on the one, and aesthetics, on the other. Anyone familiar with the last 200 years of art history knows definitive aesthetic positions are problematical, unless you're simply trumpeting your own tastes. Many serious critics find this very limited subjective criteria, (comparatives and impressionistic opinion) inadequate for arriving at a defensible position, and so seek a greater body of thought through which to process their analysis—think Husserlian phenomenology or Marx's dialectical materialism. It strikes most of us as absurd to consider animated cartoons in light of such theories as they obscure the cartoon in favor of manipulating theory. But here you tell me you eat your vegetables too, and your keen sense of formal excellence and the fact that you've talked to a bunch of guys who were there (who witnesses for the witness?) and that this all ties it up pretty fine. But I don't buy it, Mike. I just don't buy it. As someone who has pointed to the innocence of a child lovingly enraptured with the dynamic graphic photoplay of cartoons over against a lot of fussy self-styled "cartoon historians" whose pretenses to sophistication make a farce of the object of their enthusiasm and their office. No, I say, nothing has alienated me from my love of cartoons (which I've always thought are firstly a celebration of nonsense) than the tedious ramblings of the animation community itself.

From Kevin Hogan: For Mr. Alexander: I agree that it is enjoyable to read intelligent criticism on cartoons that are not necessarily classics. A book on such criticisms, or a webpage, would be very interesting. Mr. Barrier: hint hint!

For Mr. Nachman: You appear to be addressing Mr. Barrier directly, but I feel (as the person who has started this mess!) that the spirit of this conversation is lost in your post. I was never challenging Mr. Barrier’s criticism (as I stated early in my email to Mr. Barrier, I usually find his criticisms to be accurate, if not occasionally a bit harsh at times). I was not trying to say that total “innocence” is necessary in a medium like animation. I simply wanted to know if delving deeper into the history/artistry of animation takes some of entertainment/ joy out of it, especially for someone like Mr. Barrier who has devoted several decades to the medium. I think it is ridiculous to think that one cannot or should not use criticism when watching a film—one could watch anything without joy or disappointment if there is no criticism (because one would not be taking much of the artwork to heart!). I, personally, am looking for balance in animation entertainment and criticism. I never meant to assert that Mr. Barrier, or any historian/ critic, are “[obscuring] the cartoon in favor of manipulating theory.”

[Posted September 6, 2011]

From Kirk Nachman: Mr. Hogan,Mr. Barrier knows better than to tarry with verbose crackpots like myself, however it seems you're not so wary, hah-ha! Firstly, I'm sorry I've taken the conversation away from where you'd like to see it go... this is what generally happens in conversations, and I think I stick to the general subjects of the conversation: criticism, informed opinion, naked perception, etc. For one, I doubt anyone could artificially produce an absolutely innocent state for the viewing of cartoons, I'm sorry if I advocated such. I do know that people respond to different things in works of art, and often can't articulate why. The critic presumes he can. Secondly, I don't think you understood the context of my comment that certain critics will obsure the cartoon in favor of manipulating theory. I see no evidence that Mr. Barrier critiques cartoons through the prism of an over-arching critical theory or philosophical premise. His criticism tends to be more prosaic. I was simply ruminating different types of criticism, and concluded that niether the most ambitious nor the most mundane does anything to enhance my experience with cartoons. Quite the contrary. As a researcher and a documentarian Mr. Barrier is surely unrivaled, but this gathering of testament and empirical fact does not entitle his critical opinion to truth, settled law, or anything of the like.

[Posted September 9, 2011]

August 21, 2011:

Dave Hand on Ones and Twos

[An August 26, 2011, update: To read more from Børge Ring about Dave Hand and his words of animation wisdom, visit this very entertaining post on Michael Sporn's Splog.]

From famed Danish animator Børge Ring, a memory of his first meeting with David Hand, who directed Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Bambi for Walt Disney:

It was my very first meeting with the great man. Dave had agreed to meet Bjørn Jensen and me at his studio in England. We were European novices who knew cutting tables but had never seen an exposure sheet or a movieola with pegbars. Dave had written us beforehand saying that if we would read The Art of Walt Disney—the old 1942 one [by Robert D. Feild]—ahead of the consultation it would save him a lot of time.We knew this book by heart. Its pioneering author tried to convey a lot of information, some of which he himself had half understood, and the reading tattooed a few misunderstandings and left a pile of very down-to-earth questions that we hungered to hear the answers to.

I asked: "Mr. Hand: How is it with ones and twos??

Dave began: "Fast takes should always be on ones. "

I interrupted with confusion. "Yes, but Mr. Hand, in The Country Cousin the mouse jumps high up out of his pants, and he does it on twos." (We had a 16 mm black and white print.)

"Is his take vertical or horizontal ?"

'"Vertical."

"Well, vertical movements are more patient with twos than horizontal ones."

A number of like exchanges followed. Dave tired of the disorder of it all and he summed up: "Here is the rule: go ahead and animate on twos and see how far it will take you."

We pleaded with him to tell us how to obtain the Magic Feather. He got impatient and after awhile he condensed: "Look, this is what it is about. Take a situation of a man who is waiting for the bus to arrive. He has been shopping and has just one package too many. If you can animate that situation so that an audience howls with laughter, then you are an animator."

This answer crushed me and I grieved: "But what can we do to become good at it?"

Dave leaned back in his chair and asked: "Have you got a camera that shoots one frame at a time?

"Yes."

"Have you got an old projector that will run the film?"

"Yes."

"Well, that's what we had. Go ahead and you're in business. But mind you, it is not enough to be just animators. You go up to someone and say, 'Look, we can animate, we can animate.' He'll say, 'Sure you can and so what?'"

The consultation exhilarated and sobered me, and for ever after I have turned every stone on my way, looking for things that give progress.

From Michael Sporn: The Børge Ring/David Hand story is a magic feather of its own. Curiously, I'd just finished reading the Dave Hand autobiography, yesterday. There isn't one equally vibrant story about animation in that book. The information from Hand about "vertical movements are more patient with twos than horizontal ones" shows that he had an enormous wealth of knowledge that never got very far. Unfortunately, a lot of it's gone by the gutter, especially in that cgi only works on ones, and no one cares about 2D anymore. And the cgi guys don't seem to want or need such knowledge.

From Joel Brinkerhoff: I read the piece on David Hand and am a bit conflicted about losing such knowledge. Michael Sporn's comment had an interesting observation that c.g. guys may not want or need to know certain techniques because the computer makes it irrelevant. This may be true in some regards but from my experience the c.g. animators I've worked with are extremely interested in learning from traditional drawn animation and are hoping to get the timing and "readability" of motion into their media. My hope is that animators like Glen Keane will help preserve and disseminate this information and make it applicable to the new methodologies in animation.

From Børge Ring, responding to Michael Sporn's comment above: Arithmetic in the days of Tytla and Snow White could be even worse than one, two, button my shoe. You won't believe this, but In the mid seventies Richard Williams told me that Steven Spielberg wanted the standard speed of film to be raised from 24 frames a second to 30 frames—because it made transference to electronic media easier. Dick raved about the promising consequences for animation: "Cannot you see? You could do a lot more overlapping." That was one of a number of new advantages he foresaw. When I quoted him on this to Tissa David she looked speculative and asked, "But what about the crispness ?" But all of this was long before ones, twos, and threes problems were "whisked into the gutter."

[Posted August 21, 2011]

August 18, 2011:

The Lives of the Saints

The last time I visited Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome, almost three years ago, I was startled to see the glass case in the photo above. It holds what might appear to be an effigy of Pope John XXIII, who died in 1963. Not so; it's the Pope himself, whose corpse, I've read, was found to be so "remarkably fresh" when his tomb was opened a few years ago as part of the canonization process that the Vatican decided to put it on display.

For some reason, I couldn't get that glass case out of my mind as I read a news release a friend forwarded to me yesterday, about a new attraction at a famous Las Vegas casino. Here's part of it:

The legacy and creativity of Chuck Jones, one of animation’s pioneering director-producers, will be brought to life with the opening of The Chuck Jones Experience, an interactive exhibit at Circus Circus Las Vegas designed to “Educate, Inspire & Entertain” people of all ages. The attraction will celebrate its grand opening in mid-October with a press conference featuring some of animation’s brightest stars.

A four-time Academy Award-recipient, Jones created some of today’s most beloved and enduring animated characters including Wile E. Coyote, Road Runner and Pepé le Pew among many others. In 1999, with the establishment of the Chuck Jones Center for Creativity, Chuck Jones envisioned a time when people of all ages could explore their creativity…when all ideas would be welcome, when inspiration would be nurtured without prejudice, and creativity would blossom and grow. The Chuck Jones Experience, utilizing the art, writings and films of Jones, will nurture that spirit of creativity in an environment that is playful, lively, inspirational and educational. The project is being developed by Jones’ grandson, Craig Kausen, Jones’ daughter, Linda Jones Clough, and a group of Chuck Jones fans who have believed in and supported its creation for years.

“My grandfather said that if you provide the right materials and an environment of love, creative magic will come out of young people,” said Kausen. “The Chuck Jones Experience will provide kids, and animation fans of all ages, with an extraordinary place to not only learn about the art of animation, but to discover the creativity and magic that’s inside us all. We are thrilled to kick off Chuck’s Centennial year with the opening of this exciting new venture.”

The Chuck Jones Experience is a nearly 10,000 square-foot destination. At its entrance is the 1,000 square-foot glass-enclosed Chuck Jones Center for Creativity class room where creative art projects will be encouraged and guided by teachers from the field of animation and the arts. Heading inside, your first stop is the Chuck Jones Theatre, designed to simulate a 1930s-style movie theater. There, you’ll meet Chuck Jones via a short film, introduced by one of his characters, the Connecticut Cat.

Moving on, you’ll walk down a virtual street surrounded by many of Jones’ most memorable characters and a timeline of his extraordinary life. Next, you’ll arrive at a re-creation of Jones’ studio, where you’ll see how he worked, and discover what inspired him to create his beloved characters. From there, you‘ll enter the “How Do You Measure Up?” room where 3-D characters are on display. You’ll learn more about how characters are developed and experience some of the original key drawings Jones drew during the creation of these characters.

Continuing along, you can view some of Jones’ fine art work from various periods in his life and see classic photos of him, his fellow animators and his family. This leads into “Animation Alley,” a multimedia wall where animation pieces are on display from the permanent collection of the Chuck Jones Center for Creativity and from other animation studios and collections.

Finally, you’ll arrive at the Acme Workshop, where you can create your own sound effects and voiceovers for a Chuck Jones cartoon at the Chuck Jones Experience Foley Stage. You can commemorate your experience forever at the Chuck Jones Experience Gift Shop with a variety of creative gifts and souvenirs.

So, one of animation's greatest directors is to be enshrined—not literally like Pope John, thank heaven, but close enough—amid slot machines and roulette tables. I trust that those "creative gifts and souvenirs" will include a selection of votive candles.

From Mark Mayerson: I was recently in Las Vegas for the first time and except for the anthropological interest, the city was a bore. It's a completely fake city in that it has nothing authentic in it. Fake Eiffel Tower, fake Statue of Liberty, fake Liberty Bell, fake Italianate architecture, etc. It's a city for people with are satisfied with the simulation of an experience rather than the real thing. It's also a place for people who want sanitized sin, whether it's gambling in casinos that all look the same inside or watching topless shows based on current pop culture. At the hotel I stayed at, it was a topless show about vampires.

There's nothing to challenge anyone's worldview, it's all middle of the road pap.

I suspect the exhibition's presence is just another way to attract families to the city, but based on Vegas standards, it won't do anything for Jones or animation. Putting Chuck Jones there makes him more like Wayne Newton than a deceased Pope.

MB replies: I can only agree with Mark's comments on Las Vegas; but do even Wayne Newton's biggest fans go to his shows for anything more than entertainment? I can't imagine feeling entertained if I had to watch and listen to Newton for an hour or two—sounds more like torture—but, obviously, a lot of people come away from his shows happy. Entertainment does not seem to be the goal at the Chuck Jones Experience, but rather a secular equivalent (discovering "the creativity and magic that's inside us all") of what the faithful are supposed to feel when they contemplate Pope John in his glass coffin.

[Posted August 18, 2011]

From David Gerstein: Jones, like Charles Schulz and Walt Kelly, was a man whose best work, I think, is focused squarely on the expression of frustration and the backhanded humor of human frailty—yet the man's most prominent well-wishers (as opposed, perhaps, to his greatest fans) seem determined to remember him first as a beacon of all things heartwarming. Kelly, somehow, seemed to want to be remembered this way, in spite of where his talents truly lay. But I'm less convinced about Schulz, and maybe even less about Jones. Even in his latter-day period of cute Crawfords and Mark Twain mimickry, Jones seemed to make a concentrated effort to balance the sentiment in his work with elements of despair and satire. Somehow, the falsity of a Jones tribute focusing on "an environment of love" would seem to make Vegas the place for it.

From Michael Sporn: I love the briar patch of tubing they've encased with Pope John XXIII. It would only be worth visiting Las Vegas if we can see Jones encased similarly. What a way to go! Has Disney had such grandiose festivities celebrating his death? Very depressing, indeed.

From Keith Scott: I’d like to see Tex Avery lying in a glass case...the body would suddenly pop up and grin at all the people outside, a recording of his famous “hippo” laugh would emanate from speakers, and he’d whip out a big sign reading “Betcha thought I was a goner didn’t you? Giggle, giggle, giggle!!!”

[Posted August 19, 2011]

From Paul Penna: My version of Tex Avery mummified in a crystal coffin would have a sign that pops up occasionally (held by a gloved hand, of course) reading "Gruesome, isn't it?"

[Posted August 21, 2011]

From Patrick Garabedian: Regarding the pope photo you posted, I trust you realize that is not the actual corpse. The RCs often display such saints' corpses, which they say are wonderfully preserved etc. But usually , as in this case, the face and hands are covered by realistic masks. When not, you know DAMN WELL you are looking at a corpse, just as with Egyptian mummies in museums. I especially remember the decapitated head of S. Caterina di Siena ( the national female saint) on display in a church there wearing a nun's coif—empty eye sockets and lips drawn back over the teeth ! To me, horrifying, but people were busy worshipping and praying to it. Maybe I am a bit too revolted by human decay, but I have long made arrangements to be cremated.

[Posted August 29, 2011]

August 11, 2011

Interviews: Corny Cole

I remember thinking not long ago that it would be fun to post as a series my interviews with Corny Cole, Willie Ito, Dick Thompson, and other people who worked in the Chuck Jones unit at Warner Bros. in the 1950s and early 1960s. Those interviews read together give a reasonably full picture of one of the most important short-cartoon units. (In the Chuck Jones layout drawing above, think Daffy=Corny Cole, Porky=Willie Ito.) Maybe I'll still do that. But since Corny Cole died just a few days ago—and his interview is one I could put into publishable shape in a relatively short time—it seems appropriate to post it now. You can read it by clicking on this link.

From Michael Sporn: What can I say about the Corny Cole interview? The guy is all over the place but keeps coming back to "why I hate Chuck." It's not a particularly informative interview in that he doesn't really give any clear thoughts on the past except why he hates Chuck (and I'm not sure I really even understand that). You ask him how everyone else dressed at WB, and he goes off on Chuck's bow tie. There's a problem there.

He also rants on endlessly about how little money he's made. But $122 in the mid fifties was a decent salary. In 1972 when I entered the business a full time average animator made $176 according to the Union Contract. I'm sure WB did keep pushing them back to Assistant Animator (where they probably wanted them) but were trying to keep the costs down, so allowed them into story work or layout. Consequently, they could pay them less, since it took 6 months at any one craft to become a full salaried journeyman. This is probably where they were as Assistants and had to be paid full salary in that job. (Assistant journeyman paid less than storyboard journeyman or layout journeyman.)

In a way, Corny sort of drew the way he responded to your questions, all over the place. He drew with a Bic pen and just let his pen roam. His animation timing was always somewhat similar. It kept rolling. He was much better as a designer. I wish he'd talked more about some projects like The Mouse and His Child. He designed and animated on it. On Raggedy Ann he wanted to get back to M&HC so he could animate the very last scene—which he did."

From Thad Komorowski: The Corny Cole interview was fantastic, and I disagree with Michael Sporn's assessment that it wasn't particularly informative. On the contrary, it was very informative. It offers the point of view of someone who found Chuck Jones to be a prick but still liked him in a way and respected his talent. Not an uncommon stance, but one rarely expressed on-record. (For an extreme P.O.V., try Bill Melendez, who hated Jones both as a person and artist.)

It also offered interesting bits of history. I never knew Jones was planning a Western Daffy that late in the game for one, since he more or less abandoned the character to let Freleng and McKimson rape it. I had known for awhile that Norm Ferguson animated on To Itch His Own because Greg Duffell told me, who was told by Ken Harris about Ferguson's sad days at Warners, but I don't recall ever reading about it. For years I had been wondering about that anvil scene in Zoom and Bored, because it certainly wasn't the work of Harris, Washam, Levitow, or Thompson—now I know it's because none of them animated it!

There was also that little revelation about the origins of the sketches for Freleng's Tallulah Bankhead/Marilyn Monroe short. Now I'm extremely curious if it ever did get made, as a sort of theatrical commercial, but got lost to the ages.

From Jim Bennie: Corny's comments about the late-'50s Jones unit are a real insight. Jerry Eisenberg and I chatted about it (he replaced Willie Ito as Harris' assistant) but he didn't go into it in nearly the same depth. Perhaps I just asked the wrong questions.

There are always unexpected surprises in your interviews, not the least of which in this one was that Fergie worked at Warners. It's a shame he couldn't fit in with Jones. McKimson could have used a top-flight animator in the later '50s, but I don't know if McKimson had strong enough assistants that could work over Fergie's stuff.

I still don't understand the difficulty with Corny working in story. Maltese and Foster were getting paid a weekly salary specified in their union contract, I presume, regardless of how many stories they did. Why would it make a difference if someone else did a story?

MB replies: On the latter point, I think Michael Sporn's comment above is informative.

From Tom Minton: In reading your illuminating interview with Corny Cole the circumstances surrounding the death of Norm Ferguson were mentioned in passing. Corny stated that Ferguson suffered a fatal heart attack. I recall two other recollections that don't so much offer differing accounts as add a couple of personal experiences with Ferguson in his professional decline. I recall reading an interview [by John Canemaker] with Shamus Culhane published in the mid 1970's in the magazine Filmmakers Newsletter, wherein Culhane talked about hiring Ferguson to work on a commercial and then being shocked that Ferguson was mentally and physically unable to do the work. Culhane blamed Disney, stating that that studio had worked him to death over the years and had simply "pulled the guts out of him." Whether the Culhane episode happened before or after Warners hired Ferguson I don't know. The other account was given to me verbally by Harry Love in the late 1977, who insisted that Norm Ferguson was an undiagnosed diabetic and that his symptoms resembled those of an alcoholic to the uninitiated. Harry insisted that Disney had nothing to do with Ferguson's apparent sudden decline, blaming his illness. I never saw that take on Ferguson printed anywhere and wonder about its authenticity, but Harry would gladly tell anyone who asked about Ferguson the same story. As neither Culhane nor Love are still around, these accounts remain unsubstantiated but are nonetheless interesting.

MB replies: Dick Huemer, in his UCLA oral history with Joe Adamson, said of Ferguson's last days: "I remember seeing him in a bar, Alphonse's in Toluca Lake, where a lot of us animators used to go after work, and he seemed perfectly all right. The next week I heard that he'd died [in November 1957]. Fergy had been suffering from diabetes [Type II, presumably] for about 25 years." Dick's memories of Fergy from that oral history were published as part of his "Huemeresque" column in Funnyworld No. 21, Fall 1979.

[Posted August 12, 2011]

From Keith Scott: Thanks for posting the valuable Corny Cole interview. Yet again, a “non-star” name from the old days of animation provides heaps more insight into daily studio life and politicking than the endless regurgitating of Selzer-Schlesinger bashing and other inane recollections for which Chuck became tediously infamous. I think Cole’s gripe against Chuck was simply because Cole’s own nature couldn’t take ego-tripping insecurities from anyone, boss or not.

He also praised Jones at times, so I don’t see his complaints being one-eyed. Indeed the most resonant remark he made was about Chuck possessing a pronounced mean streak to his makeup: that seems to gel with the constant attempts to be intellectually above his colleagues and speaks to his long held jealousies (Clampett anyone?).

Please do post the Willie Ito and Dick Thompson interviews when you are of a mind to!! (And if you’re open to suggestions, a Phil Monroe posting would also be a fine idea.)

MB replies: I'd enjoy posting all those interviews, but the two Monroe interviews in particular will require a lot of preparation time (I don't have them in my computer), so I can't help dragging my feet.

From Steven Hartley: I never knew much about Cole but I did learn a lot in this interview. What interests me is that we find out a bit more about Ken Harris, who "seemed" impatient according to Cole, because he wanted him to get a scene right. I never really thought of Ken as an impatient person before. Have you interviewed Ken?

MB replies: I did speak with Ken Harris once on the phone, but his health was already poor then, and it wasn't possible to arrange an interview by me or Milt Gray before Ken died.

[Posted August 14, 2011]

From Børge Ring: The well informed David Hand said: "Fergy was [also] a very fast animator. But that did not make his animation economical to us, because it took expensive people to finish it." The thrifty Warners would have had to pay double for Fergy animation if they had Ben Washam finish it. But I suspect that Ben Washam would have loved the experience. Wouldn't you?

[Posted August 19, 2011]

August 8, 2011:

The Newsprint Mouse and Duck

Disney comic books and comic strips have been reprinted recently in two important new books edited by David Gerstein: the first volumes in a Fantagraphics series devoted to Floyd Gottfredson's Mickey Mouse and a Boom! Studios series reprinting very early issues of Walt Disney's Comics & Stories. I write about those books, and a lavish Danish set of Carl Barks's duck stories, in a review at this link.

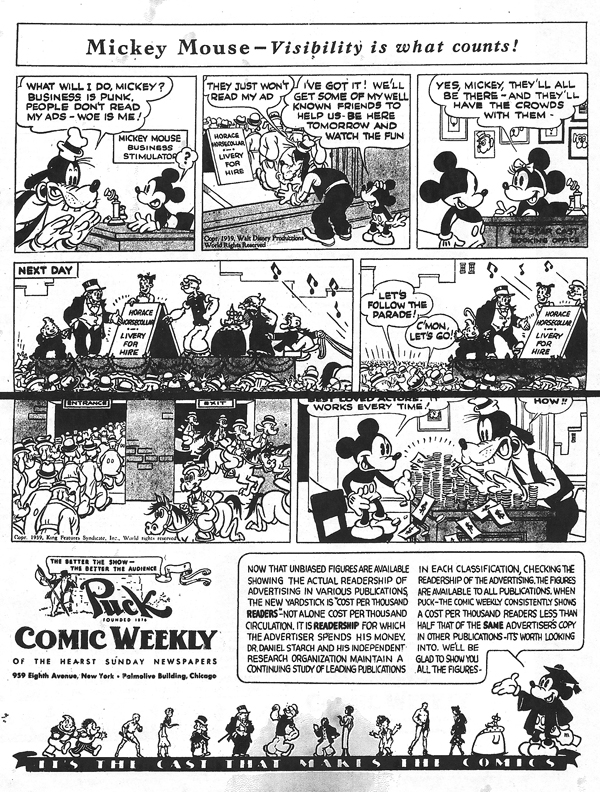

And speaking of Disney comic strips, here's an odd one that I ran across while paging through old issues of Printer's Ink magazine. It was one a series of comic-strip ads for Puck Comic Weekly, the Hearst Sunday comics section, and it appeared in the May 18, 1939, issue of Printer's Ink. I can't even guess who drew this strip (which has been distorted by the tight binding of the bound magazines). No one at the Disney studio, I'd guess, since no one working at the Hyperion studio then could have confused Goofy with Horace Horsecollar.

From Michael Sporn: Thanks for your review of the Fantagraphics Floyd Gattfredson collection. I keep circling this book and will eventually buy it. However, you put your finger on the problem I have with it: the size of the strips is so small that it'll be hard for me to read it. Your demonstration of the original newsprint version up against the reprint sure visualizes the dilemma.

When you first get to the review and see the two strips, you don't really see the Fantagraphics version. You go directly to the beauty of that original printing. You can take in so much more and enjoy it for the artwork. It's hard to do that with the smaller strips, and it's a more difficult problem for someone like me who's getting old enough to have to squint hard to read the thing. It'd be easier to have the work on a cd so that you could expand it on a computer. That goes against the best part of the strips, holding them in your hand while reading.

This problem certainly haunts the new strips being published today. I had lunch yesterday with an editor from King Features, and we discussed your review. He said that that's the number ONE complaint of every one of his artists; the strips are printed too small.

Of course, I understand the economics of the situation. But this is the reason I infrequently buy reprints of strips. The books spend too little time in my hands.

From Mark Sonntag: I just finished reading your post reviewing the Gottfredson book, as always an interesting read. I recently found a book on Carl Barks listed on eBay written by you or at least edited by you, was that a biography type book? As nobody ever tells a potential buyer what's in a book I thought I might ask you.

I did look up the Carl Barks Collection on Amazon Germany, it's a bit pricey I hope the Fantagraphics collection is using the same material. I'm looking forward to the Barney Bear collection most of all in that I didn't know until it was listed that he did other stories outside the Disney stable, the Thomas Andrae book didn't really mention it from what I can recall.

Did you know that BOOM! Studios lost the Disney license? It's disappointing as now we have no idea if there'll be more archive collections. I assume Marvel will take over the license, but who knows what their plans are.

MB replies: I assume that Barks book is Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book, which you can read about at this link. That book is still available in hardcover. Fantagraphics and I talked about a revised paperback edition, but I've set that idea aside. Barks will, however, be the most important figure in the book I'm writing now about comic books.

I'm sorry to hear that BOOM! lost the Disney license. Not because I've liked its new Disney comic books, but because it's hard for me to imagine any other publisher taking on so quixotic a project as the Walt Disney's Comics & Stories Archives.

Incidentally, anyone who cares about Disney history, early Disney history in particular, should make haste to visit Mark's Tagtoonz blog and check out his August 8 post.

[Posted August 10, 2011]

From David Gerstein: In your review of Floyd Gottfredson Library Vol 1 you point out this inconsistency:

"[The first sequence of Mickey strips] was written by Walt Disney himself and penciled for eighteen days by Ub Iwerks. Or was it twenty-four days? The book gives different answers: the table of contents says that Iwerks penciled the strip through February 8, 1930, the twenty-fourth day, whereas Thomas Andrae, in his essay on Iwerks, says that Iwerks penciled only the first eighteen strips."

This glitch originates in a discrepancy between various personnel interviews—in which Iwerks is always referred to as having pencilled three weeks—and the strip index in Mickey Mouse in Color (1988), where the four-week credit appears. I had noticed the discrepancy and meant to consult with all parties involved, then globally correct the date one way or another before presstime. In an embarrassing slip-up, I was too late to make the correction. It should really be three weeks, as now supported also by Byron Erickson (compiler of the MMIC index, who doesn't recall where the four-week date came from). It'll be fixed in the second printing.

MB replies: Another correction: I refer in my review to David as if he were the editor of the Walt Disney's Comics reprint volume, but although he filled many of the responsibilities of an editor, the official editor, as identified at the front of the book, was Boom's Christopher Meyer.

[Posted August 20,2011]