"What's New" Archives: November 2010

November 30, 2010:

November 28, 2010:

Børge Ring on Disney's Alice in Wonderland

November 15, 2010:

November 2, 2010:

November 30, 2010:

Good Housekeeping

I'm about to leave for two weeks in my former home town of Alexandria, Virginia. Phyllis and I will see many old friends, and I'll spend five or six days at the Library of Congress doing research, of various kinds but mainly for my book on comic books. I'm a research junkie, of course; when we were in New York earlier this month, I don't think I enjoyed anything as much as the few hours I spent rummaging through Bestsellers and American News Trade Journal at the New York Public Library.

The last few months have been very strange, and not only because of the prolonged remodeling of our house and multiple problems with my new computer. I've felt my interest in animation in general, and Disney in particular, all but fall off a cliff, a drop accelerated when I was writing my review called "The Approved Narrative." It was as if while writing that piece I felt the full weight of how difficult it is to carry on any sort of reasoned (and civil!) dialogue about Disney/animation/comics/etc., given all the negative factors: corporate attitudes, the resistance of most fans, the contempt in which the subject matter is so widely held (and don't kid yourself that it's not).

My website has been a victim of my general malaise. I'm sure, though, that I'll pull out of it once I get back into more sustained writing on my comic-book book. Just thinking about Carl Barks has a restorative effect, since his best stories are such a powerful reminder that what ultimately matters is the work itself, not how it's regarded by people who are themselves incapable of anything of lasting worth. It'll probably be a few weeks before I can rid myself of my gloomy mood entirely, but my time at the Library of Congress should help a lot.

I've accumulated a sizable backlog of items I want to post, and I'll start clearing up that backlog with a few of them today.

WILFRED HAUGHTON: Perhaps that British cartoonist's name rings a bell, particularly in a Disney connection; you can read a little about him at this link. I heard from Denise Haughton, who writes:

"I recently discovered that my Great Uncle, Wilfred Haughton, drew for Disney in London during the 1930's. I am currently trying to write about him and his life. I was wondering if there was any information that you would be able to pass on to me. He was the sole artist on the 1936 Mickey Mouse Annual produced in London. I know this may be a long shot but I would appreciate any help and information you might be able to give."

I know very little about Wilfred Haughton, unfortunately, but I'm sure there are those among my readers who know much more. There's now a blog devoted to the search for new information about Wilfred Haughton; you can find it at this link.

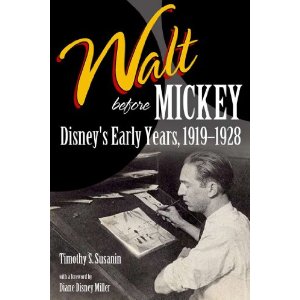

TIM SUSANIN'S BOOK: If you Google the name "Tim Susanin" at the top of my home page, for references on this site, you'll quickly learn that Timothy S. Susanin is a Philadelphia lawyer who shares my intense interest in Walt Disney's life and works. He and I have exchanged a lot of information over the last couple of years. Tim's enthusiasm for Disney-related research has, like my own, given birth to a book, in his case a remarkably detailed account of Walt's animation career in the years leading up to the birth of Mickey Mouse. Tim has made excellent use of the burgeoning online resources for researchers, letting us know, for example, just who the quixotic investors were who put money into Walt's Laugh-O-gram studio. When it's published next May, his book will automatically become a standard resource for anyone writing about the early Disney studios. Walt Before Mickey: Disney's Early Years, 1919-1928 will be published by University Press of Mississippi, one of today's most active publishers of animation- and comics-related books; Diane Disney Miller has written a foreword. You can pre-order the book now from amazon.com, at this link, and if you care at all about Disney history, you should.

TIM SUSANIN'S BOOK: If you Google the name "Tim Susanin" at the top of my home page, for references on this site, you'll quickly learn that Timothy S. Susanin is a Philadelphia lawyer who shares my intense interest in Walt Disney's life and works. He and I have exchanged a lot of information over the last couple of years. Tim's enthusiasm for Disney-related research has, like my own, given birth to a book, in his case a remarkably detailed account of Walt's animation career in the years leading up to the birth of Mickey Mouse. Tim has made excellent use of the burgeoning online resources for researchers, letting us know, for example, just who the quixotic investors were who put money into Walt's Laugh-O-gram studio. When it's published next May, his book will automatically become a standard resource for anyone writing about the early Disney studios. Walt Before Mickey: Disney's Early Years, 1919-1928 will be published by University Press of Mississippi, one of today's most active publishers of animation- and comics-related books; Diane Disney Miller has written a foreword. You can pre-order the book now from amazon.com, at this link, and if you care at all about Disney history, you should.

RSS: Dreamfeeder, my RSS program, vanished along with many others when I made the move to my new computer, and I haven't tried to replace it. RSS and Dreamweaver, my site-authoring software, do not seem to be a good fit, and Dreamfeeder did not reconcile the differences in the way it was supposed to. No one has complained about the lack of a feed, so I'll assume that no one has missed it. RSS strikes me as a great idea that doesn't work as well as it should. I rarely check my own list of feeds any more.

From Mark Sonntag: Please don't stop voicing your opinions about animation and Disney, I too can't understand some fans especially when you challenge their thinking. But your articles and books are what keep animation practitioners like me inspired. I am working on a short film which I hope will be ready next year, I can't promise anything earth shattering for my first one off the mark and being short of funds but hopefully it can springboard to something else. Your work inspires, it really does.

[Posted December 1, 2010]

From Joseph Rothenberg: Your recent post, "Good Housekeeping," had a tone of defeat I've never detected before in your writings, and I felt moved to provide some encouragement. I have been enjoying your writings on animation ever since I discovered Hollywood Cartoons in high school, but I guess if all your fans were as vocal as me, you'd never know you had any!

I remember what attracted me to Hollywood Cartoons was its surprisingly candid evaluation of the cartoons I grew up with as a kid. I had never before heard anyone speak critically about the Disney cartoons or the Warner Bros. cartoons I loved so much, and I read the book cover to cover, enjoying every minute of the well-reasoned and challenging viewpoint it provided. (I had just finished The Illusion of Life, which, though a wonderful book, is anything but critical!) From Hollywood Cartoons I found your blog, and I have checked it almost daily for the past four or five years. I particularly look forward to your commentaries on animated features, because you write about the things I care about, and you say what you think, which is so rare in animation writing. When I leave the theater after watching an animated cartoon, one of the first things I think is, "I wonder what Michael Barrier is going to write about this?"

All this is just to reinforce that your writings do not always fall on hostile ears. Your viewpoint is like an oasis in a desert for me, and I wouldn't want to see that go away.

I have written to you once before, several years ago, when I was in high school. You may remember being sent a cartoon called The Mr. Squirms Show. That was me. Now I'm studying animation at the University of Southern California, and per your kind response to that cartoon, my recent work tends to be much shorter. I don't think I'll be able to solve everything that's wrong with animation these days, but keeping your writings in mind, I try to keep a level of integrity in my work.

That's about all I have to say. Thank you very much for your excellent writings these past few years. Before I go, I'd like to recommend Tangled—it has its problems, but I felt it was something distinctly new in computer animation, and besides it has one of the funniest animated horses I've ever seen. (I also have an insidious ulterior motive; I'm hoping you'll write a commentary when you're done.)MB replies: This is a very gratifying message, but also a little sobering. I do try to say what I think, and over the years I've tried to say what I think with greater clarity and with full consideration for the people whose work I'm discussing. I'm certainly guilty of lapses in both areas, but I try to remedy those lapses when I become aware of them (see, for example, this Feedback page). Unfortunately, a great many people involved with Hollywood animation, as fans or pros, seem to say only what they think other people want to hear. Not that there was ever a "golden age" when honest discussion was the norm, but vacuous cheerleading and its corollary, vicious rejection of dissent, seem to dominate today as they did not in the past.

I did enjoy that horse in Tangled, though. I'll be saying more about Maximus, and the film as a whole, in a few days.

From Tom Carr: I'm feeling a bit of the old malaise myself, and as a fan rather than someone in the animation industry, I'll try to explain why. First of all, as I've said here before, I just can't warm up to CGI. It's not drawing, it's not live action, but instead of being either it appears to occupy some uneasy ground in between; I've never liked the look of it, and I can't understand its appeal at all. But then, as an increasingly middle-aged white male I can't understand the appeal of rap "music," either, and Eminem is currently up for multiple Grammy awards. So in both cases, I'm left scratching my head; there must be something appealing there, but don't ask me what it might be.

Admittedly, I'm a huge fan of traditional pencil animation, to the extent that I love watching pencil tests for their pure vitality (much of which is lost even in the transition to painted cels, as Frank Lloyd Wright once pointed out to Walt Disney). I just watched the trailer for Tangled and I have to say that with all the money and human resources that the Disney studio can put into a film, the characters still look like plastic Barbie dolls cavorting jerkily in videogame-like settings. It's the mountain laboring to bring forth a mouse (or in this case, the Mouse laboring to bring forth a mouse). So I'll save my money.

Now at least I'm consistent, in that my musical taste is also roughly two generations behind the times (insert link to Pilsner's Picks here, as evidence). Even so, I don't think my tastes are merely "nostalgia" for an era that I didn't live in; it's that the period from roughly 1920 to 1960 was truly a golden age of American entertainment. We didn't grab these great visual and musical art forms from some other cultures (as with, say, opera), we invented them... and that makes a difference. They're ours.

At the same time, I'm not without sympathy for all the talented people working in modern-day animation. It's very likely that if I had young children, I'd probably take them to see Tangled just for a decent afternoon's entertainment— and with the Disney name on it, I could rest assured that they wouldn't be traumatized by excessive, graphic violence (which is all to easy to produce with a computer). But Walt's original idea of making films that could appeal equally to children and adults seems to have been lost in recent years. Who knows if it'll ever come back? I have no crystal ball.

[Posted December 23, 2010]

November 28, 2010:

Børge Ring on Disney's Alice in Wonderland

The great Danish animator remembers:

I saw Disney's workprint of Alice in Wonderland at Nordisk Film in Copenhagen in 1950 when the Danish version was made. Walt and Roy were in a hell of a hurry to have the film come out and make much needed European currency. Walt's supervisor of foreign versions, a Mickey animator of the first hour [Jack Cutting], flew to Copenhagen bringing a black-and-white reel made up of prints of finished scenes plus whole sequences in pencil animation, ruff or cleaned up. The brothers did not waste time condensing the draft into the usual written continuity that merely displays the scene synopsis and the footage. They simply forwarded a copy of the complete draft carrying the names of everybody. It was the first Who-done-it of its sort that I ever laid eyes on, and the sight was overwhelming.

The timimg of Kimball's Walrus gathering oysters at the table had been drastically revised. Ward had erased the first version and drawn on top of it, but it was still readable under the new version. In the old version all the oysters except one were quickly picked up very early and locked into a Walrus embrace. Then a pause, and the last oyster was zipped up into the lot. The second and more even version is seen in the actual film.

Marc Davis's very consistent Alice was picked up by Milt Kahl in midfilm when she sits crying in Tulgey Wood. Kahl's very first scenes of the weeping girl child were much, much more realistically drawn than Marc's—and slightly unpleasant to watch. But presently she became the same Alice as during the first half of the film. From "painting the roses red" and to the end all scenes were black and white prints of the film as we know it.

I have been told recently that Walt Disney made Alice consistent all through the movie by having a cleanup supervisor make one cleanup drawing in every Alice scene. As the draft will show, her scenes were animated by many different artists from the units of Davis and Kahl.

Norman Ferguson's Walruses at the beach were lovely fresh and loose drawings, one step past "Fergie ruffs," except for the last three or four in a scene when the Walrus, cigar in mouth, descends pompously into the water to address Fred Moore's oysters. All in all, you got an impression of the drawing habits of a number of artists who animated. Their animation of water was delightful to watch in the pencil stage.

Ruff or clean, there were no scenes full of un-inbetweened keys. It was either/or. In the Dee and Dum sequence Marc Davis did a scene of Alice walking up an incline. His very first drawing of Alice at the foot of the incline was held for the duration of the yet-to-be-animated walk. From the top of Alice's head Marc or someone he trusted had drawn an undulating line that reached forward from Alice's head all the way to the top of the slope showing the postitions of her head during the coming walk. Once up there she animated again.

I could go on for hours about all this. When the dubbing in Danish was complete, this exceptional workprint was sent on to Stockholm to serve in the making of a Swedish soundtrack. I am grateful that I had had the opportunity to get this early peep into a stage in Walt Disney's workplace never seen at the time. The reel went out of sight forever but the draft came back many years later for all of us to see, to enjoy and study—thanks mainly to the passionate Disney archeologist Hans Perk, who knew the significance of the document.

You can find that Alice draft and many other illuminating Disney documents at Hans Perk's invaluable website.

From Eric Noble: Fascinating to read. I love learning these little bits of Disney trivia and such. I would love to have seen those rough versions of the animation. However, I believe they will be kept under lock and key at the Disney vault so that no outsider will know of it. Shame really, as it adds to the Disney Studios history in whatever small way it can. Alice in Wonderland will always be one of my favorite Disney films, however flawed it may be.

By the way, a young animation enthusiast named Steven Hartley has actually started posting mosaics of Alice in Wonderland at his blog. Here is the link. They may not be as probing as Mark Mayerson's mosaics, but it still is a good read.

[Posted November 29, 2010]

From Steven Hartley: I saw your post about Alice in Wonderland and I thought it was very interesting. Norm Ferguson did contribute to the animation of the Walrus and the Carpenter, but he wasn't given a lot to do; do you think the reason was because at the time, Fergy was finding it difficult to keep up with the new acting techniques of animation, or was it that many new animators came and Fergy wasn't given a lot?

MB replies: Ferguson had been on a downhill slide since the mid-'40s, when he fell out of favor with Walt and returned to animation after producing The Three Caballeros. Some of the last Disney animation that can be identified as unmistakably his, as in the Jack Kinney cartoon Social Lion (1954) is painfully clumsy. Fergy's health was poor—he died in 1957, a little over four years after leaving Disney—and no doubt that contributed to the deterioration in his work. Under the circumstances, it seems remarkable that some of his last work (as with his animation of Nana in Peter Pan) is as good as it is.

[Posted December 23, 2010]

November 15, 2010:

Sweet Sounds

Thanks to my friend E. W. Swan's computer expertise, the mp3 files in my November 2 item on Carl Stalling's acetate recordings are finally audible.

My trip to New York—which kept me from finding a solution to the mp3 problem more quickly—went very well. I saw the long-lost Disney Laugh-O-gram cartoons at the Museum of Modern Art in the company of Michael Sporn, David Gerstein, Tom Stathes and Amid Amidi. A couple of days later, Phyllis and I celebrated our wedding anniversary at the Turkish Kitchen with Michael, his wife, Heidi Stallings, and John Canemaker and Joe Kennedy. Throughout our five-day visit, I squeezed in some comic-book-related research at the New York Public Library. Phyllis and I also did a lot of things with no animation or comics connections, like seeing Bernadette Peters in A Little Night Music and La Bohéme at the Metropolitan Opera, not to mention eating lots of expensive meals. As usual, we had a great time in New York and were stunned by the cost of that great time. But, also as usual, it was worth it.

November 2, 2010:

Better Late Than Never

Thanks to the ongoing chaos in my house and my computer, I've been late in posting about any number of developments, but I didn't want to miss the chance to call your attention to the exciting rediscovery, by David Gerstein and Cole Johnson, of three of Walt Disney's Laugh-O-grams from 1922. Those films had been missing and presumed lost for decades, and almost everyone assumed that one title, Jack the Giant Killer, never even existed. You can read the full story on David's blog, and you can see two of the three rediscovered cartoons, along with several other Laugh-O-grams, this Thursday, November 4, at 4:30 p.m., at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (The program will be filled out with Ub Iwerks cartoons from the '30s.) If you're going to be in the vicinity, and you're interested at all in Walt and his films, you'll want to be there. Luckily for me, that screening fits perfectly into my own travel schedule.

Carl Stalling on Acetate

From Michael Wilkins, a fascinating discovery that I'll let him describe:

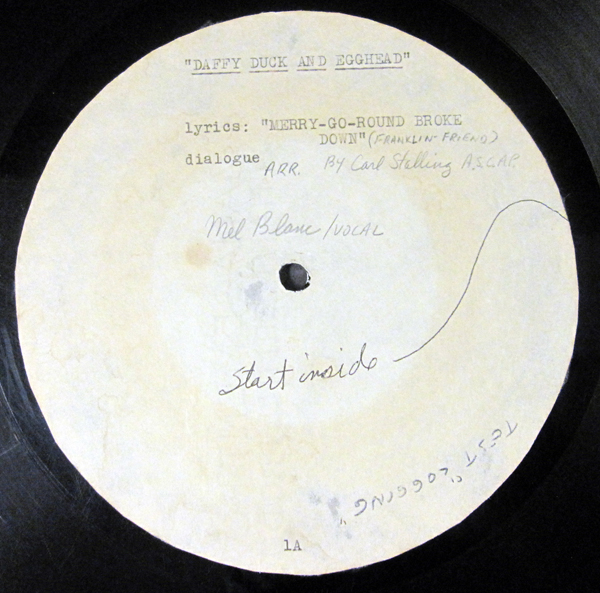

I was poking around the internet and found your Carl Stalling (Funnyworld) interview from 1971. (I was amazed that there's no "carlstalling.com" or some such place as a repository for all things Carl!) I thought you might enjoy the attached snapshots and mp3s. They come from an acetate I purchased on eBay a number of years ago (3 or 4?), and just recently "rediscovered." I did attempt to clean up the audio a bit (it's still a bit tough to listen to), but it's a gas to hear what appears to be some additional dialogue that never made it into the cartoon (or maybe I just don't remember it), as well as a stripped-down (piano only as reference?) version of "The Merry-Go-Round Broke Down." On top of that, the flip side has this little bit of what I believe to be Carl and Gladys describing the "musical members of the family."

What's on one side of the acetate is dialogue for Daffy Duck & Egghead, the Tex Avery-directed Merrie Melodie released in January 1938. There's quite a bit more dialogue than is actually in the cartoon (including a couple of direct references to Joe Penner, who remains as the ultimate source of Egghead's voice), and the dialogue that was used is out of order on the acetate. Blanc may have recorded "The Merry-Go-Round Broke Down" while listening to piano accompaniment from Stalling over headphones, with the orchestra added later, after the cartoon was complete, or nearly so. And, of course, his voice was "sped" before the transfer to this disc.

No doubt this dialogue was recorded at a point when the story was still fluid, and the disc may reflect the order in which the dialogue was recorded, by different people at, probably, different recording sessions. The disc itself is, I'm sure, an early example of the acetate discs that were recorded for the benefit of the animators, so that they could hear the dialogue instead of simply following the exposure sheets' frame-by-frame breakdown. You can listen to the dialogue side of the disc by clicking on this link.

The animators listened to that dialogue in Stalling's room at the Schlesinger studio, and what's on the flip side is almost certainly Carl having some fun with the studio's new toy, the acetate recorder (what such recorders looked like, I have no idea, although I'm sure some of my visitors do). You can hear Carl and his wife, Gladys, by clicking on this link. There's also a song, singer unidentified, but most likely with Carl at the piano; it's at this link. As Michael Wilkins observes of the song, "Sadly, it sounds like it's only moments away from the big finish, when it actually ends. Oh well." Here's more from Michael on the technical aspects of this curious disc:

First, you should know that this is a 12" acetate as opposed to the 16". And ... if I remember correctly, the "A" side (or Blanc side, for lack of a better term), does start on the inside and plays out, at 45rpm. The "B" side (or Stalling side) is different in that the first band ... is a song (Carl at the piano?) that starts from the "end" of the band—towards the middle of the record—and plays outward, similar to the "A" side. None of this is unfamiliar to those who've dealt with (or at least know about) transcription records and acetates. The second band on the "B" side plays more like a current record—from the outside, in. And again, if I remember correctly, plays at 78rpm. I'm with you—I think Carl brought home some machinery and had a little fun with it. There's more after that little fun part, but it's hard to hear what's going on—it's like the recording equipment was set up and left running while Gladys talked to someone in another room. I've not tried to decipher that bit of business yet.

I assume Daffy Duck & Egghead is available on YouTube or elsewhere on the internet, but if you're any kind of Warner cartoon fan, you should already own that cartoon, which is part of the third volume of the Looney Tunes Golden Collection.

Comments

From Tom Carr: I haven't dropped by your site in a while, but when I did, I was delighted to find the acetate recordings by Carl Stalling and friends. They're almost as scratchy as the piano recordings that Charles Ives made around the same time (also on acetate), but in both cases they're well worth a listen for their historical value... what great audio windows on the past! I noticed that there's some dialogue from the Daffy cartoon (starting at the 58-second mark) that doesn't appear in the finished film. That's from the scene where the duck orderly from the insane asylum shows up to cart Daffy away, but much to Egghead's amazement, he turns out to be just as "scwewy" as Daffy. You get an idea from this of just how improvisational these cartoons were— the directors and writers were always trying things out and changing them almost to the point where the cartoon had to be completed to stay with the production schedule. Tex might have cut this exchange out of the script himself, since he was the master of the fast-moving cartoon and he wouldn't have wanted anything that would slow one down. But that, we'll never know.

[Posted November 19, 2010]

From Brandon Pierce:That is a terrific find! There's some awesome voice acting by both Mel Blanc and the lesser known Danny Webb (doing the most spot-on Joe Penner impression ever. Honestly if you didn't know, you'd swear that really was Penner on that track). I wonder why only Blanc's name is on the record, but not Webb's (or even "Weber", as in Dave Weber). Too bad it was all cut out. But, since this whole short is more gag-oriented, Avery probably figured it worked better that way with minimal dialogue.

[Posted November 30, 2010]