"What's New" Archives: July 1010

July 30, 2010:

July 26, 2010:

July 17, 2010:

July 14, 2020:

July 7, 2010:

July 2, 2010:

July 30, 2010:

Toy Story 3

I finally got around to seeing it, and you can read what I think about it by clicking on this link.

From Eric Noble: I have to agree with you on this. Toy Story 3 was very unsatisfying for me. I only saw it once, and that's all I needed. I never really felt like I knew the characters in this film, apart from what was revealed in the previous two films. I also felt that Lotso was a big cheat as a villain. We were only told what made him a bad guy, never really shown. I felt more could have been done with him. Actually, my favorite part of the film was when Mr. Potato Head had to switch bodies and became Mr. Tortilla Head. That was the only time I ever really laughed out loud at this film. I liked the ending, which I feel was appropriate for this film. Ultimately, I see it as Pixar resting on their laurels, putting out good films but not living up to the potential they showed in other films like The Incredibles.

BTW, I disagree with you about Inception. I felt it was a very coherent film for the most part. Although the first fifteen minutes were a bit confusing, I found it quite easy to follow. I wonder if it seemed incoherent to some due to the nature of the subject, but I can't be sure. I will have to see more films about dreams if I'm going to make any comparison.

MB replies: I haven't yet seen Inception; I was relying on the reviewers, who have been uniformly baffled. I've been surprised that none of the reviews of Inception that I've read mentioned what would seem to be generally similar treatments of dreams, like Satoshi Kon's animated feature Paprika or some installments of the Neil Gaiman comic-book series Sandman. But maybe Inception differs more from those earlier dream stories than it would appear.

From Patrick Malone: "In TS3, Andy, the toys' owner, has reached college age, thus the question, what is to become of his playthings? Will their destination be the attic, a daycare center, the city dump, or, in Woody's case, Andy's dorm room?" Wasn't that the plot of The Brave Little Toaster except with appliances instead of toys?

MB replies: It has been many years since I saw Brave Little Toaster, and about as long since I thought about it, but I think there's a critical difference between the appliances in the earlier film and the toys in TS3. I can easily imagine an older teen/young adult feeling a sentimental attachment to old toys, but a sentimental attachment to old appliances, and especially to something like an old radio? Not likely. That would be like feeling a sentimental attachment to my first computer, which I was more than happy to scrap when I bought a better one. Such things exist to be superseded, but toys, since they can be vehicles for the imagination (a point that TS3 makes, I think rather crudely, in its opening minutes), can't be made obsolete in the same way.

From Tom Carr: Luckily, I don't have young kids to drag me to a theater to watch anything like this. Whatever the reason is, I just can't get used to computer animation. Why is that? I've asked myself, and the best answer I can come up with is that it occupies an uneasy ground between live-action film and traditional pen-and-ink animation. To come straight to the point, it just doesn't look right. For example, compare Pinocchio, which is arguably the greatest of the Walt Disney features, technically. The characters all have weight and mass in addition to having strong personalities, but there's never a moment of doubt that you're watching moving drawings. So it works as a pure cartoon, and it works superbly.

The Pixar stuff is neither good nor bad to me, I just shrug my shoulders... I suppose it entertains a lot of people, since it makes so much money. I'll take a black and white cartoon from the 1930's any day, instead. Even if they're primitive, they still have more impact and visual substance than this "moving plastic." Or whatever it is...

[Posted July 31, 2010]

From Elliot Cowan: I've enjoyed your thoughts on Toy Story 3 (via a link from Michael Sporn's blog). I didn't like it much. I don't feel it's a bad film especially, but I didn't find it very compelling.

After rewatching the first two films again recently, I realised that I enjoyed them most when the toys are confined to a household. The only parts of #3 I liked at all were scenes set in bedrooms. As the film makers have become more "ambitious" the Toy Story films have become more overblown. Many have spoken of the emotional moment in #3 when the toys realize they are going to hell (or whatever the incinerator is supposed to suggest). I found it so surreal, so removed from the familiarity of the bedrooms and hallways of that I all I could think was how weird and silly it was.

I'm glad people love these Pixar films. Personally, they've left me feeling like a confused outsider for years now. What is it that I am not connecting with, I wonder?[Posted August 11, 2010]

July 26, 2010:

Milt Gray's Web Comic Strip

Milton Gray, a leading Hollywood animator for many years, was also my indispensable collaborator when I was editing Funnyworld and writing Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. He has been an occasional contributor to this Web site and others—the "Flip Book" in the right-hand column is his—and now he has launched a site of his own, a continuing comic strip. "Ms. Viagri Ampleten" is a spy spoof with a spectacularly endowed amazon as its title character. The strip will be updated every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, starting Wednesday of this week. To start reading with the first installment, click on this link.

July 17, 2010:

In Brief

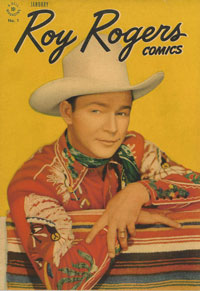

UNHAPPY TRAILS: Six years ago, I wrote about my visit to the Roy Rogers-Dale Evans Museum in Branson, Missouri. I said then that walking through the museum was "a little like having Roy say to you, 'Come into my den and let me show you my collection of autographed baseballs.' I was hoping for a series of exhibits that would embrace the lives and careers of both stars and place them in the context of movie westerns and Hollywood in general, but what the museum offers instead is amiable clutter, much of it better left in the attic." A lot of other people must have agreed, because the museum, suffering from declining attendance, closed late last year. This month, its contents—including Roy's stuffed horse, Trigger, as well as a few animation-related items—went up for auction at Christie's in New York. Many if not most of the auction prices exceeded estimates, sometimes by wide margins; Trigger went for $266,500, Roy's saddle for almost $400,000. Evidence, perhaps, that Roy and Dale still have a lot of fans, even if they didn't want to visit Branson to pay homage to their heroes.

UNHAPPY TRAILS: Six years ago, I wrote about my visit to the Roy Rogers-Dale Evans Museum in Branson, Missouri. I said then that walking through the museum was "a little like having Roy say to you, 'Come into my den and let me show you my collection of autographed baseballs.' I was hoping for a series of exhibits that would embrace the lives and careers of both stars and place them in the context of movie westerns and Hollywood in general, but what the museum offers instead is amiable clutter, much of it better left in the attic." A lot of other people must have agreed, because the museum, suffering from declining attendance, closed late last year. This month, its contents—including Roy's stuffed horse, Trigger, as well as a few animation-related items—went up for auction at Christie's in New York. Many if not most of the auction prices exceeded estimates, sometimes by wide margins; Trigger went for $266,500, Roy's saddle for almost $400,000. Evidence, perhaps, that Roy and Dale still have a lot of fans, even if they didn't want to visit Branson to pay homage to their heroes.

The copy of Roy Rogers Comics No. 1 at right is from own collection; I don't recall seeing any comic books at the museum or listed for the auction. Odd.

MICKEY'S THE WORD: I posted an item on May 31 about the use of "Mickey Mouse" as a password for a meeting of naval officers that preceded the D-Day invasion in 1944. At that point, I knew of three U.S. newspapers that had published a brief United Press item about the meeting. Now more such reports have come to light, thanks to a correspondent who prefers to remain anonymous and, indirectly, the Disney archivist Dave Smith. A UP story was published in the New York Herald Tribune on June 8, 1944, and a somewhat longer and more detailed story, evidently not originating with UP, was published in the Johannesburg (South Africa) Sunday Times for June 11, 1944. It seems likely to me that all these stories originated with some as yet unidentified source, possibly a British newspaper. And where did that meeting of naval officers take place? So far there's no more specific location than a "southern port."

HARVEY PEKAR: The passing earlier this month of Harvey Pekar, the writer and proprietor of the American Splendor comic books, was marked by full-length obituaries and essays in major newspapers. I can't think of any other true comic-book person, except possibly Carl Barks, who received such respectful attention upon his death. The best of the pieces I've read is Jeet Heer's appreciation in the Canadian National Post, which benefits immensely from Heer's very extensive knowledge of the comics. I once followed closely everything Pekar did, starting in the '70s with American Splendor No. 2 (I still don't have No. 1, which is no doubt out of my price range), and I'm a little sorry now that I let my attention fade in recent years. Pekar and I corresponded in the early '70s, pre-American Splendor, and he wrote a piece about his friend R. Crumb for Funnyworld No. 13, in 1971; you can read it by clicking on this link. My own extended consideration of Pekar's work took the form of a review of the movie version of American Splendor, in 2003; I think that piece holds up very well, and you can find it at this link.

HARVEY PEKAR: The passing earlier this month of Harvey Pekar, the writer and proprietor of the American Splendor comic books, was marked by full-length obituaries and essays in major newspapers. I can't think of any other true comic-book person, except possibly Carl Barks, who received such respectful attention upon his death. The best of the pieces I've read is Jeet Heer's appreciation in the Canadian National Post, which benefits immensely from Heer's very extensive knowledge of the comics. I once followed closely everything Pekar did, starting in the '70s with American Splendor No. 2 (I still don't have No. 1, which is no doubt out of my price range), and I'm a little sorry now that I let my attention fade in recent years. Pekar and I corresponded in the early '70s, pre-American Splendor, and he wrote a piece about his friend R. Crumb for Funnyworld No. 13, in 1971; you can read it by clicking on this link. My own extended consideration of Pekar's work took the form of a review of the movie version of American Splendor, in 2003; I think that piece holds up very well, and you can find it at this link.

FACEBOOK: I still haven't gotten into gear as far as Facebook is concerned, and I think my unanswered "friend requests" total in the many dozens. If you've asked to be my friend, and I haven't responded, don't take it personally.

From Michael Sporn: Thanks for the update on the Roy Rogers Museum. I spent many nights in Madison Square Garden where Roy and Dale hosted a Rodeo. They looked to me, as a cub scout on an outing with the troop, like wax works on parade—they were so shiny. There was so much glitz and flourish from them as they paraded around on Trigger and Buttercup, both animals doing their share of tricks for the crowd. Plenty of American flags everywhere and a special set of tricks by Bullet. "Happy Trails" played at the end as they sang (or lip-synched) that song. A disco ball threw glimmers of light over the entire audience. All of their shows ended the same way. They and their show will stay in my memory for life.

I've curiously followed their adventures in building the museum but, other than your comments, I haven't heard much about the follow up. You paint a sad story, but perhaps it was inevitable. I always imagined the Triple "R" ranch with a stuffed Trigger in the front yard, even though I suppose that couldn't be a reality. Just the same, that's probably how I'll continue to think.

MB replies: My one experience of Roy Rogers in the flesh could hardly have been more different. I was a very young reporter for the Arkansas Gazette at the time—this must have been 1966 or '67—and I somehow got assigned, very late one Saturday evening, to cover a press conference being held by a local wheeler-dealer who had roped Roy and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. into involvement of some kind with a grand real-estate project. There were several photographers in attendance, but I was the only reporter present, I suppose because the press conference had been scheduled at such an odd hour. It followed the serious business of the evening, which was, as I recall, putting the two stars on display to impress potential fat-cat investors in the host's project.

If you remember Audrey Hepburn's press conference at the end of Roman Holiday, it was sort of like that—everyone remained standing the entire time—with me playing all the reporters asking all the dumb questions. The circumstances definitely did not encourage questions about show-business careers, so I asked Roy and Fairbanks inane questions about their current activities. The press conference ended quickly, in an atmosphere of subdued embarrassment. I never even got to shake Roy's hand. He passed within a foot or two of me as he left the room, but he made a point of keeping his eyes averted, and I took what seemed like a strong hint.

Seeing Roy at Madison Square Garden would certainly have been more fun. As it happened, I saw very little of him when I was growing up, except in the occasional movie like Melody Time. He was for me almost exclusively a comic-book character.

[Posted July 21, 2010]

From Brent Swanson: I'm sorry to say that the Rogers-Evans Museum was about the same or even worse when it was in its Victorville location. There was a small room dedicated to the marketing of the duo, featuring comic strips, records, toys, and posters, but I don't remember seeing any comic books. Given the ambience of "morality" that flooded the place like a mudslide, it could be that comic books weren't welcome.

I decided (after two visits) that the museum was more about Leonard Slye and Lucille Smith than Roy Rogers and Dale Evans. It was as though the two were trying to cash in on their alter-egos while repudiating Hollywood, sort of like having cake and cursing it too. The low point of the museum for me was Roy's old parade limo, which had previously borne the Apple Valley address of the museum, till somebody slapped what appeared to be housepaint over the old lettering and marked the Victorville address over the top of it.

There was talk for awhile that the museum was going to become part of a big new Victorville development called "Rogersdale" that would feature the museum, a shopping center, and an entertainment complex. Instead, it moved to Branson.

I mentioned that I was there twice. I had enough of it the first time, but my mom wanted to see it, convinced that I had sold it short in my (then) youth. I'd sort of hoped she was correct. We went in and I was discouraged all over again in about fifteen minutes. I went to see how mom was doing. She shook her head and whispered, "This is just a collection of junk."[Posted July 27, 2010]

July 14, 2010:

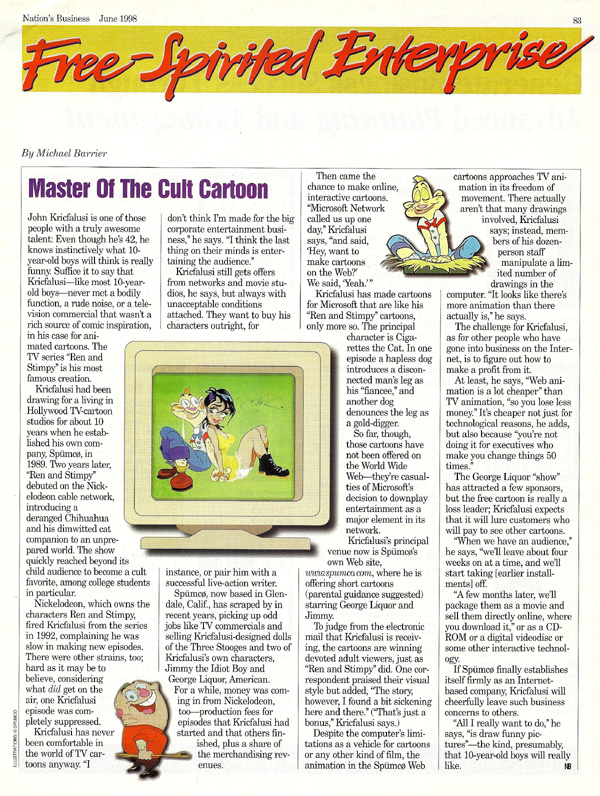

Interviewing John K. in 1997

Back in the late '80s and early '90s, when I worked for a magazine called Nation's Business, my job for several years was to travel around the country and interview interesting small-business people, or, occasionally, interesting people who had owned a small business at some earlier point in their lives. Those few years were easily the most enjoyable of my sixteen years with the magazine, since I got to spend hours or even days with people as varied as Sam Walton, Julia Child, Dick Clark, and Charles Schulz. Then and later, even after my formal duties with the magazine had changed, I seized opportunities to interview and write about small-business people with animation and comics connections. Bill Melendez was one, and he was, predictably, a lot of fun; Will Vinton was another, and I remember him as cold and suspicious.

When I was in Los Angeles in November 1997, I interviewed John Kricfalusi at his studio, which was then on Melrose Avenue in Hollywood. My story was eventually published in the June 1998 issue, on the page called "Free-Spirited Enterprise." I recently ran across that story when I was going through some old files, and that's it just above. To call up a much larger and therefore more readable version, click on the page or on this link. You can also hear an audio clip from the interview by clicking on this link (MP3 player required); in it, Kricfalusi acts out what was planned to be a downloadable "Christmas card" starring his characters George Liquor and Jimmy the Idiot Boy.

John K. was in 1997 near the end of what might be called the Charming Young Eccentric phase of his life, and I think it's interesting—and more than a little sad—to measure what he said then against the wreckage of the ensuing years, the wretched Adult Cartoon Party in particular. It's too bad he didn't continue making cartoons for ten-year-old boys instead of cartoons whose intended audience seems to have been hopelessly degenerate sixty-year-old men.

Speaking of reprints of my earlier work: Michael Sporn, whose "Splog" is essential reading/viewing, has posted (with my approval) a piece I wrote for Millimeter magazine late in 1976 about the films of John and Faith Hubley. It was published just before John's death in February 1977, and just a couple of months after I'd interviewed him in New York. I remember writing that piece in a hurry, and it has rough edges that make me wince now, but I think it holds up pretty well overall.

From Thad Komorowski: Thanks for the scan of your John K. article from years ago. It's a sad reminder of how hollow John's "you'll see, you'll ALL see" routine ultimately ended up being. He was taken to meetings with top people in Hollywood by Ari Emanuel, courted by celebrities who loved him and his work (Aerosmith, Joel Silver), and was paid well (not Dreamworks well, but well enough) by Nickelodeon to not work on Ren & Stimpy. It's a little more shameful than sad that one of animation's most promising filmmakers just didn't make films with the cards in his favor.

[Posted July 15, 2010]

From Ricardo Cantoral: John Kricfalusi seems to be his own worst enemy. He has the talent and initiative to create a fine product but his nature to be totally uncompromising has cost him plenty. Every time one of his projects sank he did not learn from his mistakes; he simply increased his resolve not be bothered by the jeers he received from his network bosses, his peers, and his audience. Sure, there were times where the circumstances prevented him from achieving his goals. His first George Liquor Show was far ahead of its time but as short as those cartoons were, no one was going to have the patience to wait for them to load on a dial-up connection. Also the production of the second Liquor show was halted by the bankruptcy of the main sponsor, Pontiac. Still, John could have had made at least one more hit show had he not alienated the people he worked with. I think he should be content now because he has finally found a venue where he doesn't have to please anyone but himself: writing a blog about cartoons as opposed to making them.

[Posted July 19, 2010]

From Eric Noble: I'm here to comment on your post on interviewing John K. in 1997. It is an interesting article, and a bit sad. It's sad to see how his career has turned out. At least now he is taking time to teach the next generation of cartoonists all of the necessary skills. I just hope that they learn to take his lessons with a grain of salt, and to not let his biases affect their judgment.

[Posted July 29, 2010]

From Brian Olson: Reluctantly I have to agree with most of your post-1997 analysis and the commenters. I miss the restrained yet playful and subversive cartoons John K. produced.

John K, at the very least, could have been what JibJab is today. Imagine using the profits from such a venture and funding his own animated folly.[Posted September 16, 2010]

July 7, 2010:

The Mysterious Mouse, Cont'd

On September 3, 2009, I posted an item headed "The Curious Case of Mortimer Mouse," which I illustrated with an image from the Walt Disney Family Museum's Facebook page. That image was a sheet of sketches identified as "The Earliest Known Drawings of Mickey Mouse." The oddest of those drawings was of a mouse of the general Johnny Gruelle kind, fussier in clothing and in physical attributes—that is, a little more like a real mouse—than the Mickey who appeared for the first time, in the spring of 1928, in Plane Crazy. This "Little Lord Fauntleroy Mouse," as I called him, never appeared on the screen but turned up repeatedly in print in later years (as evidenced by my September 4 and September 10, 2009, posts) to show what Mickey had supposedly evolved from.

Back on May 5, Didier Ghez wrote on his Disney History blog about a precursor of that "Fauntleroy mouse":

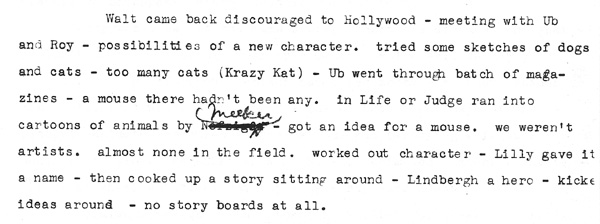

I was working this weekend on an interview with Ub Iwerks conducted by Bob Thomas in the mid-'50s (and which will appear in Walt's People - Volume 10) in which Ub recalls the creation of Mickey Mouse as follows:

"Walt came back discouraged to Hollywood [from his meeting with Mintz in New York] and set-up a meeting with Roy and I to discuss possibilities for a new character. I tried some sketches of dogs and cats, but there were too many cats (like Krazy Kat). Then I went through a batch of magazines. In Life or Judge I ran into cartoons of animals by [Clifton] Meek and got an idea for a mouse. We weren’t artists. There were almost none in the field. We worked out the character: Lilly gave it a name, then we cooked up a story sitting around."

What Didier was doing with that Thomas interview (as he explained in a subsequent post) was translating Thomas's very rough typewritten notes into something readable. Here's what the typewritten notes actually look like:

Someone on the Archives staff made my photocopy of the notes during one of my research visits in 1994 and accidentally lopped off the right side of the page, but I don't think anything critical was lost.

Bob Thomas's notes referred originally to "Nofziger"—presumably Ed Nofziger, a magazine and newspaper cartoonist who specialized in animals—but that reference was corrected by someone—I can't identify the handwriting—to "Meeker." Although Leslie Iwerks, in her heavily slanted biography of her grandfather, takes that reference to "Meeker" literally, there seems to be no question but that Iwerks was thinking of Clifton Meek, who drew mouse cartoons in the teens and twenties. Meek himself wrote about his Disney connection in "A Tribute to the Late Walt Disney," in the Norwalk (Connecticut) Hour, on February 23, 1967; there's a link to that article in Didier's post, but it's also available through this link at the English-language Google News site.

Bob Thomas's notes referred originally to "Nofziger"—presumably Ed Nofziger, a magazine and newspaper cartoonist who specialized in animals—but that reference was corrected by someone—I can't identify the handwriting—to "Meeker." Although Leslie Iwerks, in her heavily slanted biography of her grandfather, takes that reference to "Meeker" literally, there seems to be no question but that Iwerks was thinking of Clifton Meek, who drew mouse cartoons in the teens and twenties. Meek himself wrote about his Disney connection in "A Tribute to the Late Walt Disney," in the Norwalk (Connecticut) Hour, on February 23, 1967; there's a link to that article in Didier's post, but it's also available through this link at the English-language Google News site.

In that article, Meek referred to an interview with Walt in the June 30, 1944, New York Post. I located that interview on microfilm, and I've already cited it once before, in my May 31 item about the use of "Mickey Mouse" as a D-Day password. In the interview (which took place about two weeks before it was published), the reporter, Mary Braggiotti, quotes Walt as citing Meek as an influence in his choice of a mouse as his cartoon star: "There was a man named Clifton Meek who used to draw cute little mice and I grew up with those drawings. They were different mice from ours—but they had cute ears." (Meek in his tribute left off that last sentence, perhaps because it diluted the connection between his mice and Walt's mouse.)

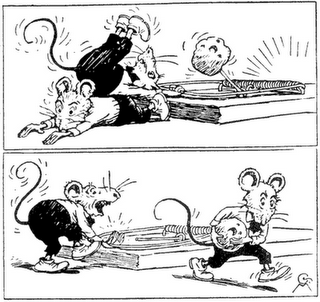

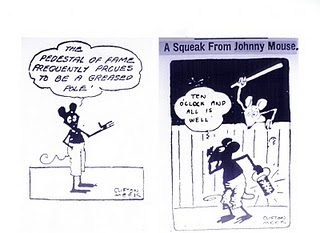

Didier reproduced some of Meek's drawings (which can also be found on the page for Meek at the Lambiek Comiclopedia) with his post, and I'll borrow one of them here; you can see what Walt may have meant by "cute ears," and it's in those ears, if nowhere else, that you can see a possible connection with the early Mickey.

Or was Walt referring to Meek's earlier and more schematic mice in his "Johnny Mouse" cartoons, an example of which you can see in the accompanying 1914 cartoons from the Pittsburgh Press? Gunnar Andreassen included that cartoon in a message that Didier posted on May 13. Meek says in his article that he was drawing "Johnny Mouse" as early as 1912, in San Francisco, and apparently it was syndicated (by, Meek says in that 1967 article, the Scripps-McRae syndicate) for several years at least.

Or was Walt referring to Meek's earlier and more schematic mice in his "Johnny Mouse" cartoons, an example of which you can see in the accompanying 1914 cartoons from the Pittsburgh Press? Gunnar Andreassen included that cartoon in a message that Didier posted on May 13. Meek says in his article that he was drawing "Johnny Mouse" as early as 1912, in San Francisco, and apparently it was syndicated (by, Meek says in that 1967 article, the Scripps-McRae syndicate) for several years at least.

The questions here are many: When and how did Walt see Meek's cartoons? He "grew up with those drawings," so he must have seen them in the teens. But did he see both kinds of mice? Did a Kansas City newspaper carry Meek's "Johnny Mouse"? (I haven't checked yet, on microfilm or otherwise.) Or was Walt thinking of Meek's cartoons published a little later, in humor magazines like Life? Presumably he saw Meek's mouse cartoons before Meek began devoting himself to the comic strip called "Grindstone George," which the Lambiek Comiclopedia dates to 1916-1919.

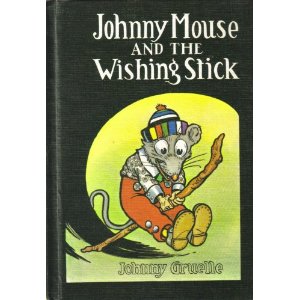

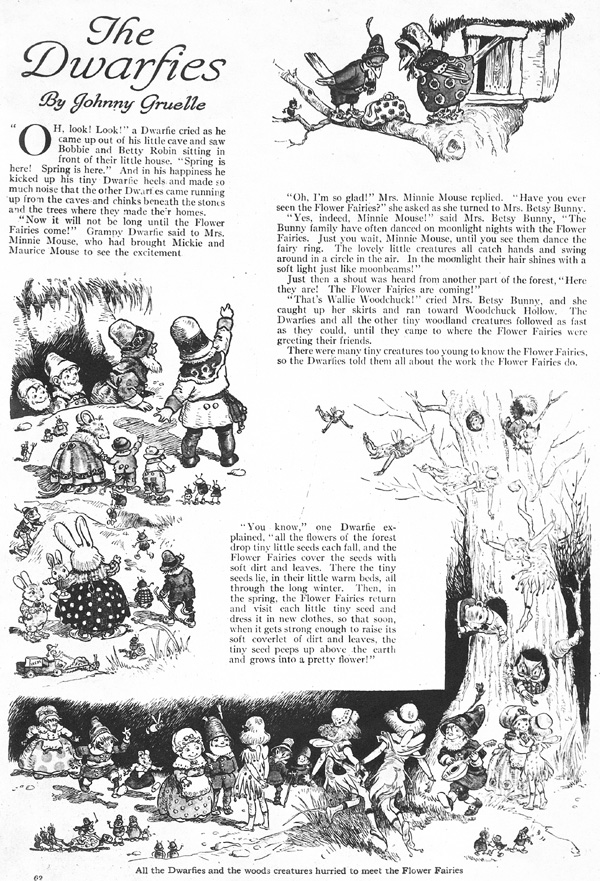

Along the same lines, is the drawing of "Fauntleroy Mouse" on that early sheet a recollection of Meek's Gruelle-like mice, or was it inspired by Gruelle's own subsequent drawings of similar characters? Meek and Gruelle were friends, and it was at Gruelle's urging that Meek moved to New York, almost a hundred years ago. There's no reason to believe that Meek took umbrage at Gruelle's use of fully clothed animal characters similar to Meek's in the 1920s, in books like Johnny Mouse and the Wishing Stick (1922) and in the 1920-21 Good Housekeeping feature called "The Dwarfies." I've reproduced below a "Dwarfies" page from the April 1921 Good Housekeeping; the story's cast includes three mice named Mickie, Minnie, and Maurice.

Then again, maybe all these questions about influences are a little beside the point. Walt and his colleagues admired some cartoonists' work more than others, but when it came to designing characters, intensely practical considerations were most important. In the crisis precipitated by the loss of most of the Disney animators, having a workable design at hand had to count for more than any aesthetic preferences.

Then again, maybe all these questions about influences are a little beside the point. Walt and his colleagues admired some cartoonists' work more than others, but when it came to designing characters, intensely practical considerations were most important. In the crisis precipitated by the loss of most of the Disney animators, having a workable design at hand had to count for more than any aesthetic preferences.

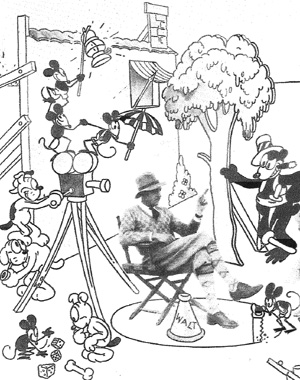

When George Sherman of the Disney staff interviewed Ub Iwerks on July 30, 1970, what Iwerks said about Mickey's origins, according to Sherman's notes at the Disney Archives (I don't know that Iwerks was ever tape recorded), was significantly different from what he told Bob Thomas fifteen years earlier. Walt Disney was gone, and with him, perhaps, any lingering temptation to exaggerate Iwerks's own role in the creation of Mickey Mouse. "I don't recall any special meetings or discussions on how Mickey should look," the notes have Iwerks saying. "Back in 1925 Hugh Harmon [sic] did some sketches of Walt's characters, and they were photographed around Walt. A couple of little mice looked like Mickey. The only difference was in the shape of the nose. We decided to make Mickey the size of a little boy. We couldn't have him mouse-size because of scale problems. We asked ourselves, 'What are people gonna think?' The size we selected must have been right—people accepted him as a symbolic character, and though he looked like a mouse he was accepted as dashing and heroic."

I've reproduced part of that 1925 publicity photo/drawing at the left; it's on page 40 of the original 1973 edition of Christoper Finch's The Art of Walt Disney. Hugh Harman's mice are smaller than the Mickey of Plane Crazy—there was no need to be concerned about scale in such a drawing—but there's a strong general resemblance otherwise. The differences between these mice and the original Mickey may be even more telling, though—and more indicative of Walt's own contribution to the character—for reasons I wrote about in Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. I think now that I probably gave Iwerks too much credit for designing Mickey (as opposed to making the earliest drawings of the character, which he almost certainly did), but otherwise what I wrote seems to me to be on target:

I've reproduced part of that 1925 publicity photo/drawing at the left; it's on page 40 of the original 1973 edition of Christoper Finch's The Art of Walt Disney. Hugh Harman's mice are smaller than the Mickey of Plane Crazy—there was no need to be concerned about scale in such a drawing—but there's a strong general resemblance otherwise. The differences between these mice and the original Mickey may be even more telling, though—and more indicative of Walt's own contribution to the character—for reasons I wrote about in Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. I think now that I probably gave Iwerks too much credit for designing Mickey (as opposed to making the earliest drawings of the character, which he almost certainly did), but otherwise what I wrote seems to me to be on target:

"There was nothing particularly innovative about Plane Crazy or its mouse star. He was a formulaic mouse of a kind that had long been plentiful in competitors' cartoons, and in some of Disney's own, too—Alice's Circus Daze, for instance. Like many of the mice in Paul Terry's Fables, the earlier Disney mice had simple faces—essentially white masks composed of eyes and muzzle—on otherwise black bodies, a characteristic that they shared with Felix and Oswald and many other animal characters of the twenties. ... Typically, though, the mice in Terry's Fables had pointed and downturned noses, fried-egg eyes, and long, skinny ears; in Mickey's design, the snout turned up, not down, and the ears were emphatic circles, rather than blown back. Mickey was a much more positive-looking character than the earlier mice, and although Ub Iwerks surely deserves most of the credit for Mickey's design, the cast of the character's features was very much in keeping with the emphatically optimistic tone that Disney himself adopted."

And there's something else. In 1940, Walt Disney said that as late as 1930, "my ambition was to be able to make cartoons as good as the Aesop's Fables series." At least two silent cartoons in that series, released in the months just before Walt made his first Mickey Mouse cartoon, Plane Crazy, had as lead characters a mouse couple roughly the size of Disney's Mickey and Minnie, and generally similar to them otherwise. Three years later, Disney sued Fables' producer, the Van Beuren Corporation, for imitating Mickey and Minnie too closely. Disney was successful, even though the Fables people had a ready-made defense in that Disney's cartoons resembled some of their silent cartoons about as closely as theirs resembled his. But Paul Terry, who made the cartoons with the mouse couple, had been fired by Fables, in the turmoil surrounding the transition to sound, and it may be that no one at the Fables studio in 1931 even remembered those old cartoons with the two mice. If Walt remembered them, he never let on. Better, and perhaps safer, to remember Clifton Meek's mice instead.

Thanks to Gunnar Andreassen and Peter Hale for their input into this post.

From Mark Sonntag: Another great article, I recently picked up Fantagraphics reprints of the Krazy Kat comics and thumbing through the books it struck me how similar Ignatz looks to the early Mickey, well at least the round ears. I do vaguely remember reading somewhere that Walt was a fan of George Herriman at least at the time when he wanted to be a newspaper cartoonist, I'm not sure where I read that or if it is even true though there is condolence letter from Walt to Herriman's daughter Mabel reprinted in the volume covering the years 1943-1944. I guess all artists are influenced by what they see and absorb through their lives.

[Posted July 9, 2010]

From Peter Hale: It can be hard enough, sometimes, to follow the sense of a recorded interview: taking notes can lead to even more ambiguities. In Thomas's notes I presume that "We weren’t artists" is Ub’s explanation for resorting to the time-honoured tradition of looking-to-see-what-other-people-have-done when you need inspiration. But "almost none in the field" can be read as either a continuation of that theme—very few professional cartoonists working as animators—or a return to the idea of a mouse—very few mice as featured characters.

As you will recall, mice had featured heavily in the promotional material for the Disney Brothers/Walt Disney studio since the Alice Comedies, where mischievous mice decorated the lobby cards, through the Oswald series, where the end card shows a mouse having written "THE END" on the seat of Oswald’s pants. It is interesting that despite Ub's Meek detour Disney seems to have had these mice more in mind (just blown up to three feet tall—the height of the typical animated cartoon character of the day, it would seem!).

And that Disney brothers' card to their father—is it known what year that was?

[Posted July 14, 2010]

July 2, 2010:

Krazy, Kool, And Kollected

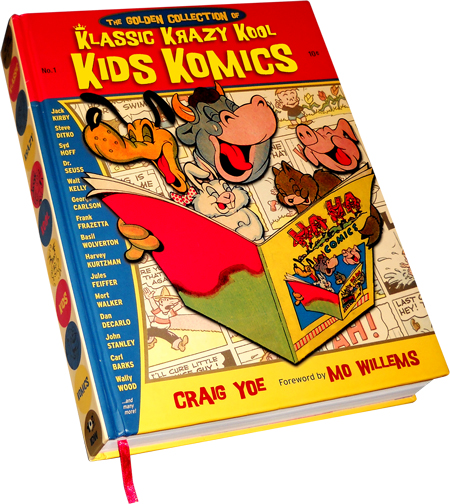

Craig Yoe, whose Complete Milt Gross Comic Books and Life Story I recommended here on April 1, has just published another volume of comic-book reprints, The Golden Collection of Klassic Krazy Kool Kids Komics, an anthology of comics, mostly from the 1940s and 1950s, aimed at younger children. I can recommend your purchase of the new book, too, but first, some background information may be helpful.

Craig Yoe, whose Complete Milt Gross Comic Books and Life Story I recommended here on April 1, has just published another volume of comic-book reprints, The Golden Collection of Klassic Krazy Kool Kids Komics, an anthology of comics, mostly from the 1940s and 1950s, aimed at younger children. I can recommend your purchase of the new book, too, but first, some background information may be helpful.

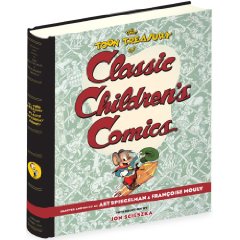

Yoe is a controversial figure in the small world of serious comics researchers and historians, as I learned early last year when I was helping Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly assemble the comic-book stories in their volume published as The Toon Treasury of Classic Children's Comics. Spiegelman, Mouly, and their publisher, Abrams, were aware that Yoe was planning a similar book, and so they felt under tremendous pressure to get their Toon Treasury completed and on sale by last fall. They made it—the book was published September 1, beating Yoe's into print by more than six months.

The big difference between the two books is that Yoe made his selection entirely from comics in the public domain, whereas Spiegelman and Mouly cast their net much wider, to include a high percentage of stories still under copyright. Obviously, working only with PD material offers considerable advantages to the compiler, whose principal task in assembling a book will be to locate copies of the comics he wants to reproduce. As I learned in gathering the stories reproduced in A Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics, and as Spiegelman and Mouly experienced with their book, negotiating with copyright holders can be tiresome and frustrating.

But if those negotiations are successful, the result can be a better book, as is certainly true in this case. Yoe includes one story each by Carl Barks and John Stanley, but there's none of Barks's Donald Duck or Uncle Scrooge, or Stanley's Little Lulu, since those stories are still under copyright; Spiegelman and Mouly offer healthy samplings of both. There's PD material in the Spiegelman-Mouly book, too, and their selection of stories is open to question on several grounds, but the overwhelming sense in the The Toon Treasury of Classic Children's Comics is of a serious effort to include only stories that really deserve to be read by today's children, whether they're under copyright or not.

I don't think it's possible to interpret the selection of comics in Yoe's book in quite the same way, even though Yoe does his best, in his introduction and in the presentation of his material, to make the case for what a cover blurb calls "this stunning collection of the greatest kids comics." Most of the stories in the book, like most comic-book stories of every kind, are simply not very good. Well, no, worse than that, they're bad, by any reasonable measure. They were obviously written and drawn in haste, usually by young men who needed money fast, to be read by children who had few other diversions to choose from when television was still in its infancy. Like most of my friends, I turned up my nose at such comics when I was a kid—I had much more appealing alternatives available, like Barks, Stanley, and Walt Kelly, all in their prime, and I knew the difference—and they don't look any better now.

I don't think it's possible to interpret the selection of comics in Yoe's book in quite the same way, even though Yoe does his best, in his introduction and in the presentation of his material, to make the case for what a cover blurb calls "this stunning collection of the greatest kids comics." Most of the stories in the book, like most comic-book stories of every kind, are simply not very good. Well, no, worse than that, they're bad, by any reasonable measure. They were obviously written and drawn in haste, usually by young men who needed money fast, to be read by children who had few other diversions to choose from when television was still in its infancy. Like most of my friends, I turned up my nose at such comics when I was a kid—I had much more appealing alternatives available, like Barks, Stanley, and Walt Kelly, all in their prime, and I knew the difference—and they don't look any better now.

Which doesn't make Yoe's book any the less fascinating because it contains so much really odd stuff.There's some overlap in artists with the Spiegelman-Mouly volume, but less than you might expect (and no overlap in stories), and the overall feeling of the two books is remarkably different. Yoe offers a couple of hypnotically terrible funny-animal stories by Jack Kirby, for example, and a cheerfully ugly one by the great Terrytoons animator Jim Tyer. There's the complete Adventures of Mr. Tom Plump, from the mid-nineteenth century, which Yoe describes (inaccurately, I think, but it's still worth a look) as "the earliest known American comic book for kids," and "Pigtales," a story about a couple of porcine characters by that nice Jewish boy Harvey Kurtzman. Familiar names (not just Kirby but also Frank Frazetta, Steve Ditko, and Dr. Seuss) turn up in unfamiliar roles.

Not everything is Klassic Krazy Kool Kids Komics is peculiar—there's a Walt Kelly fairy tale, and Dan Gordon's genial "Superkatt," and nicely drawn if generally tame stories by George Carlson, Ken Hultgren, Wallace Wood, and Jack Bradbury—but the prevailing atmosphere is more than a little strange. If you want to experience what it was like to be an omnivorous young comic-book reader circa 1950, you could do worse than immerse yourself in Klassic Krazy Kool Kids Komics. Just imagine you're in your pediatrician's waiting room and there's a big stack of comics on the table, comics the doctor or his nurse bought without caring what was in them as long as they were "funny," and you're there.

I said earlier that Craig Yoe is a controversial figure in the comics-reprint world, and if you want to know why, a good place to start is with Jeet Heer's piece on Yoe's Complete Milt Gross Comic Book Stories. The rap on Yoe, basically, is that he assembles his public-domain projects too hastily, and so makes too many errors, and that his books soak up sales and attention that should go to researchers who are taking the time to do the job right, and whose books are therefore slower to get into print. I spent decades writing Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, during which time I was beat to market by Leonard Maltin and any number of other writers, so I can't help but sympathize with such complaints. Ultimately, though, I don't think they're persuasive.

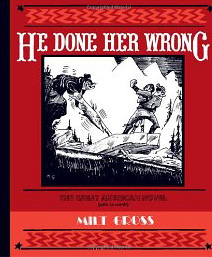

What matters most in the case of Yoe's Gross volume is not whether it's "complete" (evidently it's not), or that there are a few errors in the biographical introduction (evidently there are), but that the book reproduces a lot of Gross comics that we would be unlikely ever to see otherwise. When more comprehensive and carefully researched books about Gross are finally published—Mark Newgarden and Dan Nadel are at work on one—I can't imagine that they will include more than a few of the comic-book pages in Yoe's book. (The Complete Milt Gross Comic Book Stories and The Toon Treasury of Classic Children's Comics have one Gross story in common; it looks better in the Spiegelman-Mouly book, but I'm not sure if that's owing to superior printing or to better source material.) This is not a case, as with Neal Gabler's Walt Disney biography or David Michaelis's Charles Schulz biography, in which a seriously deficient book has made it impossible for better books to get attention or even be published at all.

What matters most in the case of Yoe's Gross volume is not whether it's "complete" (evidently it's not), or that there are a few errors in the biographical introduction (evidently there are), but that the book reproduces a lot of Gross comics that we would be unlikely ever to see otherwise. When more comprehensive and carefully researched books about Gross are finally published—Mark Newgarden and Dan Nadel are at work on one—I can't imagine that they will include more than a few of the comic-book pages in Yoe's book. (The Complete Milt Gross Comic Book Stories and The Toon Treasury of Classic Children's Comics have one Gross story in common; it looks better in the Spiegelman-Mouly book, but I'm not sure if that's owing to superior printing or to better source material.) This is not a case, as with Neal Gabler's Walt Disney biography or David Michaelis's Charles Schulz biography, in which a seriously deficient book has made it impossible for better books to get attention or even be published at all.

As for those Gross comic-book stories in Yoe's book, I think they're less-than-prime Gross (they were published circa 1947, soon after Gross suffered a heart attack) but still very much worth reading. They're distinguished especially by cartoon drawing that's wonderfully free and energetic but always under control. Nothing in cartoons of any kind—comic strip, comic book, animated cartoon—is more attractive than lines so full of energy that they seem to rocket across the page of their own volition, and Gross' drawings always had that kind of energy.

But if you want to read Gross at his absolute best, you need to read He Done Her Wrong, from 1930, his "great American novel (with no words)," where the drawings have just as much energy but more graphic variety (and are funny as hell besides). I've owned for many years the 1963 Dell paperback edition of that book, with the drawings reproduced too small, and it was only recently that I discovered the full-size (I assume) Fantagraphics reissue of four years ago. I wouldn't care to be without Yoe's Gross collection, but if you could own only one Gross book He Done Her Wrong would be the one to have. Besides Gross' inimitable drawings, the Fantagraphics edition offers an astute appreciation by Paul Karasik and an introduction by—what do you know! Craig Yoe! As I said, it's a small world.

From Jeet Heer: Your comments on Yoe are fair enough and I haven't had a chance yet to read his Golden Collection of Klassic Krazy Kool Kids Comics. I wanted to add three points: 1) As I tried to indicate in my review, I am grateful for the Yoe's collection of Milt Gross comics despite its flaws and my hope that there will one day be a better book on Gross. 2) My memory is that the Toon Treasury was planned and annouced before Yoe's Golden Collection of Klassic Krazy Kool Kids Comics. I'm not sure that point came through clearly enough in your review. 3) I think careful selection is very important in an anthology. One reason why I cherish the Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics you co-edited with Martin Williams is that it is very clear you made a serious effort to select the best stories from the early comic books; this was especially evident I think in the stories you selected by Barks, John Stanley, and Harvey Kurtzman. I think the Toon Treasury was edited with a similar rigour and that's the standard by which comics anthologies should be judged (as against complete reprint projects, which have a different mandate).

MB replies: I'm not sure it makes much difference which anthology was announced first; if Yoe said to himself, "Hey, that's a good idea, but I think I can do the same sort of book better," why not let him try? (I was aware of the impending publication of Neal Gabler's Disney biography when I signed a contract to write mine, but I didn't feel that I owed any deference to Gabler, and I was certainly right.) If both anthologies had been published simultaneously, as Art Spiegelman feared would happen, a likely outcome would have been more publicity, and larger sales, for both books, with the edge undoubtedly going to the Spiegelman book, both critically and commercially.

I think it's worth emphasizing just how difficult it is to edit a comic-book anthology with any sort of critical rigor (and here I speak from my experience with the Smithsonian book). Most comic-book stories, of every kind and from every period, are simply not very good; the great majority are junk. If the Toon Treasury reflected that reality with true rigor, it might contain the work of a half dozen or so cartoonists—Barks, Stanley, Kelly, Wolverton, Kurtzman, and one or two others, not the two dozen or so who are in fact represented. Given that reality, I can feel a certain sympathy for Craig Yoe's approach, which in its essence seems to have been to find the weirdest possible copyright-free stuff by the most familiar possible names. As I indicate in my review, I think he succeeded, perhaps all too well.

And speaking of Craig Yoe...there's an online interview with him at this link.

[Posted July 12, 2010]