"What's New" Archives: October 2009

October 30, 2009:

October 29, 2009:

October 27, 2009:

October 22, 2009:

October 20, 2009:

October 14, 2009:

October 13, 2009:

Groucho, Harpo, Chico, Zeppo—and Walt?

October 12, 2009:

October 9, 2009:

October 2, 2009:

October 1, 2009:

He Slices! He Dices! He's Interactive!

October 30, 2009:

Those Magic Moments

Christian Renaut writes from France:

Dear Disney historians, Disney artists or more largely Disney employees or former Disney artists, gallery owners or relatives of deceased Disney artists, artists working in the animation business, this message is for you!

After having published two French books on Disney animation (From Snow-White to Hercules prefaced by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston and The Disney Heroines prefaced by Glen Keane), I am starting in earnest work on my third project. Its title will probably be The 20 Greatest Moments of Disney Feature Animation.

That’s where you might get involved. Instead of imposing my standpoint, I intend to do a kind of poll or survey if you are willing to help. The book will be an analysis of 20 great “moments.” It is on purpose that I didn’t use the word “sequence” or “scene” as I want it to be very free, although we may expect the moment to last a certain length of time. So, I’m asking you to select your 20 favorites, justifying, explaining and also giving details or anecdotes about these moments of Disney animation. For instance if you were a young artist working with the old timers, I’m sure you have a lot to tell.

The criteria are all yours. You may judge it from a layout standpoint, or because of a wonderful storyboarding, or a great song, or an outstanding animation, or because it is very funny or moving, or because of the colouring/styling, or the backgrounds, or because you are stunned by the special effects, etc. But we could also think that an excellent combination of most of these criteria might lead to THE choice.

Yes, I know how silly it may sound to have to just select 20 moments when some features like... (oops, stop, no influencing anyone!) already contain at least 20 great moments. That’s why I have decided to split it all into two legitimate parts: 20 "greats" when Walt Disney was alive and later on, I will do another investigation for the other part, i.e., the features since his death. For now, I’m asking you to focus on [the features from Snow White through The Jungle Book].

I will try to make a book with new information, as usual, based on interviews, but also with hardly ever or never-before seen artwork. It will surely be long in the making, but never mind! Thanks in advance for your participation, please think it over and send your mails to christian.renaut@wanadoo.fr

October 29, 2009:

"Sincerity"

My post of a few days ago called "Lost Illusions" has generated just a few responses, but I particularly liked one from Geoffrey Hayes, which gave me the chance to explain some of my thinking about that Disney shibboleth called "sincerity." You can go directly to the Hayes comment and my response by clicking on this link.

From Milton Gray: You mentioned that if you were in charge at Disney's today, you would lock up the Animation Research Library and tear down the Xerox copies of great animation scenes that paper too many walls, but you barely hinted at why. My belief is that you were thinking that the new animators should do more original thinking about who their new characters are, rather than apply someone else's past work inappropriately—and especially to stop people from indulging in an unearned sense of greatness by association with someone else's work. That very sense of unearned greatness encourages people to get lazy and not do great work.

MB replies: Exactly right.

[Posted October 29, 2009]

From Gordon Kent: You gotta be sincere" from Bye, Bye Birdie....

Actually, I wonder if it's sincerity.

Personally I feel that what has gotten in the way of most animation (not just Disney) is a fear of real human emotion. If that's what you meant by sincerity then we are in agreement.

Real, honest, human emotion is what makes Dumbo and Snow White so brilliant to me and what is so lacking in current Disney films. It's not so much the cynicism and smarmy sit-commy retorts, but the fear of genuine feeling in the characters. Bambi, Pinocchio and Dumbo are filled with a genuine sense of charm and humanity.

I haven't seen any of The Princess and the Frog so I have no idea whether or not there is any real humanity there... I'm not sure how to reinsert it into these stories, but I can tell you that the place to start firing employees is at the executive level, not the artists level. The artists are told what to do by the executives and if they don't, they're gone. What you see in these films is not the artist's vision, but that of the executives.

I'd also like to say a word about story. Most stories are not allowed to deviate in any way from the Robert McKee theory of writing. All the executives take his course and send all their writers and story people to take the course as well (I was sent to it...). I can't say they all own well-annotated copies of his book, but I wouldn't be surprised if they do. I believe that the reason for this is so the executives and the artists can speak the "same language." It's makes it easier for the executives to get their way.

There is a standard formula that runs through almost all Hollywood (to say all Hollywood may be correct, but I'm known for exaggeration so I will try to avoid that.). This is the reason you can almost always predict what will happen next in any movie—and almost always be correct.MB replies: For those not familiar with Robert McKee, you can visit his Web site by clicking on this link. McKee claims that his former students have written most of the recent Pixar features, as well as Shrek and The Simpsons Movie. Maybe that explains something.

From Peter Hale: What made the early Disney features so good, it seems to me, was that they were breaking new ground. Nobody had any preconception of what an animated feature "should be like," and all involved in the productions were just anxious to make them succeed. The shorts of the '30s had been a constant push to improve the quality of animated films—but it wasn’t about ‘animation skill’ per se, rather about Walt’s goal of connecting with the audience through recognition: he wanted the characters’ performances to ring true, to be in character, so that audiences would become caught up in the "reality" of the situation. Not photographic or naturalistic reality, but recognisable emotional credibility: comedy—and pathos—built by burlesquing real, familiar situations.

To this end Walt’s men—only later to be compartmentalised into animators, storymen, layout artists, etc.—didn’t just concentrate on ways to give their actions more impact (the now familiar animation skills) they studied fine art (for ways of making their drawings, layouts and colour usage more effective), vaudeville (for constructing comic routines), and live-action films (for character performances, story-telling techniques and creative editing) looking for ways to just "do it better." They were primarily visual artists—indeed they were so unsure of handling dialogue in the beginning that they resorted to rhyming couplets, which could be declaimed in comic style without needing to sound convincing. All the time Walt was trying for the depth of content—albeit in caricature form—of the regular feature film, and this was where he wanted the studio to go: not just because shorts did not command enough money but because he wanted his work to be the main program, not just the filler. He wanted to make films, and cartoon animation was his vehicle.

When they embarked on the early features they knew they were back at square one—they had mastered the animated short but now they had a whole new challenge: to sustain audience involvement for an hour or more. And if they got it wrong the studio would face liquidation! (Not that they were afraid of such consequences—they were young and enthusiastic, and entranced by Walt’s vision—but it made success the more important.) They built on what they had learned on the shorts—how to develop story through situation and sequence, and how to show through pantomime what personality a character was and how he was interacting with the others.

This was their key strength, born originally out of the lack of desire (indeed, inability) to create great dialogue. All of the dialogue in their films was born of the need of the situation—just what the character needed to say, in the way he would say it—they were creating pictures (snapshots, sketches) and the dialogue was just necessary detail. (It has been said that when eventually writers were hired to join the storymen they were bewildered to find that writing was the last/least thing they were expected to do.)

The early Classic Features consist of meticulously contrived sequences—like shorts—that further the storyline through the interaction of characters: a steady flow from setup through escalation to conclusion that had been honed through many story meetings, then leica reels—sometimes to be completely overhauled mid-production—until it was working as well as they could make it. Nobody is giving that kind of attention to story any more—either visually or imaginatively.

If the original animation team drew inspiration from the best of '30s Hollywood, it sometimes feels that today’s equivalents are aping the worst of made-for-TV. That Princess and the Frogopening? Too bitty, too talky—and just one great shot (the walk down the corridor, with the shadow action on the wall) which stood out like a sore thumb instead of being merely a high point in a feast of visual story-telling. Yes, forget the Disney legacy—the worst parts of the Classics were always when they were doing something they’d done before, when they thought they were on safe ground with a familiar piece of "shtick."

[Posted October 30, 2009]

October 27, 2009:

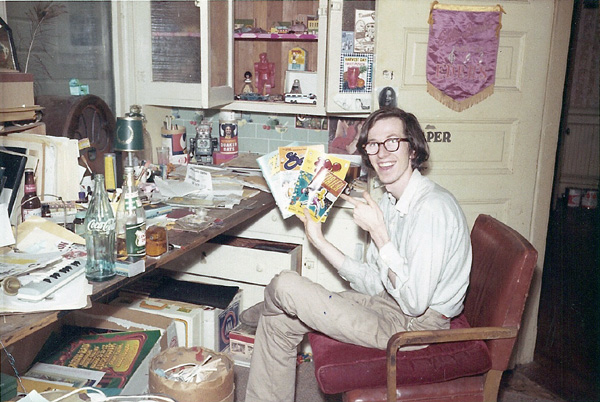

R. Crumb by W. Kimball, 1968

R. Crumb by W. Kimball, 1968

Ward Kimball gave me this snapshot of Robert Crumb, the great underground cartoonist, when I interviewed him for the first time, at the Disney studio on June 6, 1969. The photo is dated December 1968, which I believe is when Ward first met Crumb, in San Francisco. I was publishing Funnyworld in those days, and Ward had written to me about Crumb in November 1968: "Have you seen Robert Crumb's new comic book, 'SNATCH'? I dare you to run reproductions from this pubic hair-raiser in 'Funnyworld.'" (No, I didn't take him up on that dare.)

From Tom Carr: I've met Crumb, but only once—and it was a complete accident. I just ran into him on the street in San Francisco early on a Sunday morning in 1992 or '93. I really can't remember which year it was, but it must have been only shortly before he moved to France. Of course, he looks like no one else, so I recognized him right away. Being a pushy native New Yorker, I introduced myself, shook hands, and told him that I'd been a fan of his ever since I was in high school. He sort of mumbled a "thank you," and he has the limpest dead-fish handshake I've ever experienced. I got the feeling that even though we were out on the street on a quiet morning with no one else around, I was somehow intruding on his private, personal space. So I figured that I'd better "keep on truckin'," which I did. What I think is that Crumb doesn't happen to really like anyone outside of his immediate family—I'm not always the most sociable person myself, but at least I'm polite when I meet someone for the first time. He's not. This happened not too far from Sixth Street, where I believe Maxon Crumb still lives; it's one of the roughest neighborhoods in a city that has quite a few. The scenes of Robert sketching the passers-by on Market Street in the Terry Zwigoff film were shot on the block of Market between Sixth and Seventh. A veteran S.F. cop once told me, "Sixth is just like the yard at San Quentin." You don't even want to walk there in the daytime, much less after dark! So my experience of meeting Crumb was a definite letdown, but after seeing the Zwigoff film, I was at least glad that I hadn't asked him for an autograph.

[Posted October 28, 2009]

From Carl Russo: I, too, ran into Crumb. It was around 1980 on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley. There was no mistaking him, as he really appeared as he drew himself—in vintage clothes avant la lettre. I said, "Excuse me, are you R. Crumb?" "No," he scowled, and walked away.

I have been selling off the remaining stock of a once-great underground comix collection on eBay. One particularly nice Crumb item I put up for auction got an email response from his brother-in-law, Alex. His sister Aline married Robert and they live next door in Sauve, France. Alex buys back old Crumb comix, has the artist sign them, then resells them on eBay for much bigger bucks.

Some may see it as gauche, but I think it's a good way for Crumb to get a piece of others who have profited from his artwork.

[Posted December 17, 2009]

Walter K. to Walter D., 1960

Walt Kelly wrote to Walt Disney on May 25, 1960, a friendly letter—mostly about fund-raising for epilepsy research—that includes this paragraph:

Just in case I ever forgot to thank you, I'd like you to know that I, for one, have long appreciated the sort of training and atmosphere that you set up back there in the thirties. There were drawbacks as there are to everything, but it was an astounding experiment and experience as I look back on it. Certainly it was the only education I ever received and I hope I'm living up to a few of your hopes for other people.

(The carbon of Kelly's letter is at Ohio State University; the original is presumably at the Walt Disney Archives in Burbank.)

October 22, 2009:

Lost Illusions

On its Web site, Powell's, the great Portland, Oregon, bookstore, offers a daily review, from a wide variety of sources, of interesting books that you may want to buy—from Powell's, of course. Earlier this month, the "Review-a-Day" was from The Nation, by its art critic Barry Schwabsky. He wrote about a book called The Extreme of the Middle: Writings of Jack Tworkov. I consider myself fairly well educated in modern art, but I'm embarrassed to say that until I read Schwabsky's review I couldn't have told you that Tworkov was one of the pioneers of Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s. The first paragraph of the review made me sit up straight:

Almost any fable of the artist's life could take its title from the novel about the life that Balzac wrote, and that stands as a model for the rest: Lost Illusions. Yet Balzac may have been too optimistic. Showing his would-be poet Lucien Chardon seduced by his social ambitions and undefended by any strength of character, a man who throws away his talent by selling out, Balzac implicitly defends those who labor with integrity as heirs to greatness—and its rewards. So we all hope. But experience teaches that greatness is rare, and perhaps no less so among the upright than among those of questionable character. A sadder novel than Balzac's could have been written about the lost illusions of those who with patience and determination remain true to their intuition of the artistic absolute yet never attain inner certainty of their achievement or even scant public acclaim for it. But how much recognition would be enough anyway? In exchange for its near-extinction in the exigencies of form, the ego demands twofold repayment. The artist's demands on his public are typically as unappeasable as those he makes on himself. Although the pleasures of Jack Tworkov's writing are many, The Extreme of the Middle is a book I'd recommend to aspiring artists as a warning: this is how depressing it can be to be a serious, successful artist.

Reading that, I first thought, yes, that's right—unfortunately. Then I thought about the times, blessedly rare, when my wife, being a wife, has said to me, you're a good writer, why don't you write something that will make some real money, instead of writing books about animated cartoons and comic books? I've always said to her, in effect, that if I were to try to do that, I'd lose the satisfaction of writing about things that matter to me—and I probably wouldn't make more money, anyway. You can't unleash your inner Dan Brown or John Grisham if there's nothing at the end of leash.

I'm sure there are many people making animated films or "art comics" who approach their work in a similar spirit. But I wonder how many are fully aware of the risks that Barry Schwabsky lays out. The emotional price of pursuing your goals with integrity can be very high, and there's always the possibility that the work into which you've poured your heart and soul will ultimately prove to be, in the eyes of your intended audience and even yourself, considerably less than dazzling.

But the risks may be even more serious, and more complex, than Schwabsky suggests.

I thought about Schwabsky's review while I was watching the opening six minutes of Disney's The Princess and the Frog on the new Blu-Ray set of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The bits and pieces of the film I'd already seen were discouraging, to say the least, but the extended excerpt was awful beyond my worst fears. The tone was aggressively smarmy, and the animated "acting" was not just coy and self-conscious in the odious Don Bluth manner, it was also as crude as anything I've seen in those low-grade TV sitcoms whose actors do nothing more than assume attitudes and avoid looking at the camera.

And yet the awfulness on the screen had been executed with a high level of skill and even dedication. There's every reason to think that many of the people who worked on The Princess and the Frog believed in what they were doing as much as Jack Tworkov did. And I don't doubt that when the film opens later this year, it will be greeted with a flood of mostly adoring comments on Cartoon Brew and other such bulletin-board blogs, especially those that cater to Disney geeks. The mainstream media reviews will be mixed but basically favorable, and curiosity, if nothing else, will drive the film to a respectable showing at the box office.

So, the people who made the film—a good many of them, anyway—will have "remained true to their intuition of the artistic absolute" and won considerably more than "scant public acclaim." But The Princess and the Frog, unless it's much, much better than we have any reason to expect, will stand as a monument to the unyielding uncertainties of the artist's life. In years to come, I'm sure that at least a few of the people who worked on it will say to themselves, when they measure what they actually accomplished against the hopes and ambitions that brought them into animation in the first place: "This is really not what I had in mind...not what I had in mind at all."

From Donald Benson: In the '80s there was a very good British play titled Benefactors by Michael Frayn. It was mainly about power shifts within and between two married couples, but one character's personal arc addressed the Princess and the Frog issue.

The character was an architect engaged to design a public housing project, and he had visions of creating a genuine community modeled on a college.Over the course of the play he's forced to deal with the bureaucracy and practical issues, gradually leading to the kind of cold efficient apartment block he despised.Finally the project is killed by politics. By now the design is 180 degrees from what he set out to do, but instead of letting it die the architect reflexively continues to fight for it at the expense of his career, getting a reduced version built as an office property.

That, I think, is what happens to a lot of big projects, artistic or otherwise. First people accept the compromises in the fight to protect the vision, then somehow end up fighting for the compromises themselves—sometimes at the expense of whatever vision is left.It's not so much a matter of selling out or surrendering as of Wile E. Coyote, angrily trying to spring a failed trap while standing in the middle of it.

[Posted October 22, 2009]

From Michael Sporn: Your piece on Lost Illusions certainly struck a chord. I also remember the play Benefactors well and was pleased to be reminded of it. I've found myself in the position of defending compromises far too often in the quasi-commercial films I've made.

You've also hit the nail on the head regarding my feelings about The Princess and the Frog. I haven't even seen the six-minute opening, but I have seen the trailers. From the first, I was turned off. The movement was lush and full and sarcastic in the way of all TV shows. Watching the smug frog turn back to the audience to share a nasty moment with them just pushed me out of that film. However, I wonder if such compromises are the work of the "artists" or their bosses. This is what poses as humor today and can be found on all the worst of sitcoms.

I hope we're both wrong about this film, but I can't expect that to be the case. It doesn't look like it'll be the savior of 2D animation.

[Posted October 23, 2009

From Geoffrey Hayes: I continue to find your blog fascinating even when I don't agree with your opinions. You have the ability to help me view things in a new light, as regards your recent piece on Barks's Donald Duck and his varied roles. It never occurred to me that Donald switched roles with such regularity depending on the story yet still retained the same basic character. I also loved your (not too) recent blog on Don Bluth's animation. I always knew that there was something that bothered me about his films (apart from the jumbled stories.) The very slickness of the animation and attention to detail not withstanding, what his films present are animators exposing their techniques.When Michael Meyerson ran some animation drawings from Lady and the Tramp my first response was, "Oh, there's Tramp!" not "Oh, there's Frank Thomas!" even though I've known for years who animated him. To me, Bluth's style reached its apex not with Anastasia but with Thumbelina, surely the most self-conscious animated character ever put on film. Her entire "performance" is a series of tics, gestures and expressions meant to invoke reality but creating the opposite effect. I won't even go into the clashing styles of the character design.

This brings me to your latest post on The Princess and the Frog. By this time I expect you to be negative regarding current Disney/Pixar animation, but I was stunned to find just how negative you were about PATF, so I re-watched the five minute sneak peak on the Snow White Blu-Ray. Then, I watched it again. I tried in vain to find anything "smarmy" about it, or "awful beyond belief." What I saw was what promises to be a sweet story with quite a bit of the old Disney magic. Sure, the character of Charlotte is obnoxious, but I believe she's supposed to be. Other than that, what do you find so "odious"?

Of course, it's not Snow White or Pinocchio. How could it be? Those films were made seventy years ago. PATF was made by arguably the best living animators working in the Disney mode, men who cut their teeth on Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast. According to directors Ron Clements and John Musker, John Lasseter initiated a new practice, one that Pixar uses, by having all the animation critiqued by all the animators, not just the directors. Therefore, you can't lay the blame on individual animators, or Musker and Clements or John Lassiter. If there is a problem, then it is pervasive. The animation archives are available for the animators to study. Clearly they have, as the frog designs and animation in this film harken back to Wind in the Willows. So, what would you suggest as a solution, practical or not? If Disney hired you as a consultant and you went in to address the animation department, what would you tell them?

John Lasseter is interested in making quality films. I agree with you whole-heartedly regarding Wall•E and Bolt. But even those are heads above the junk the other studios are producing. I happened to very much enjoy Up if for no other reason than that is was original in every respect. This is why I admire Quentin Tarantino. These days, when most films seem to be recycled from every other movie, it's refreshing when someone takes a chance on something new. I think with The Princess and the Frog Disney intentionally didn't go too far out on a limb, but meant to recreate the kind of film it does best. I'll at least reserve my judgment until I see it. I guess I'm not clear exactly what you expect. What was the last Disney hand-drawn film you loved? Anything beyond One Hundred and One Dalmatians?

MB replies: Actually, no; and I wouldn't say I "love" Dalmatians, certainly not the way I love Snow White and Dumbo, although I think it's a very good children's film, thanks largely to Bill Peet.

I remember years ago working my way through all the Disney features then available at the Library of Congress, starting with Saludos Amigos (this was long before any Disney features were available on videotape), and growing steadily more annoyed by the time I got to The Jungle Book, because more and more of what I saw on the Steenbeck monitor's screen seemed false. Much of what I saw was delightful, of course—I think immediately of the mice and the cat in Cinderella, of the March of the Cards in Alice, the "Willie" sequence in Make Mine Music, dinner at Tony's in Lady and the Tramp, Hook's seduction of Tinker Bell, and so on—but what came in between the delightful moments was increasingly problematic, until finally what I felt as falseness swallowed up most of The Sword in the Stone and The Jungle Book.

I think the falseness I saw was rooted, paradoxically, in that Disney shibboleth "sincerity." As Walt used the term, during work on the first great features, it was the characters who were to be sincere, that is, to seem to move of their own volition. Over the years, sincerity came to be valued less in the characters than in their animators (and, at one step removed, their directors), until now we are supposed to admire animation because its practitioners—assuming a high level of technical skill—are conspicuously earnest, in a way that many of the great early Disney animators were not. It's hard to imagine someone as gifted and irreverent as Ward Kimball, in particular, surviving for very long in the current environment (Kimball had a hard enough time surviving in the Disney of the late '50s and early '60s).

What this earnestness means in practice is that Disney-style animators have a powerful incentive not to venture beyond the obvious, because of the risk that what is not obvious will make them seem insincere. Couple that with the self-consciousness that is Bluth's legacy, so that characters seem real only in their awareness that they're performing for the camera in a ridiculous story, and you have the dreariness that I see in those opening minutes of The Princess and the Frog, in which utterly empty and unbelievable characters have been animated by people whose work fairly aches with sincerity. (How can we not admire what they've done, when we can see how much work has gone into it?)

If I were hired as a Disney consultant, I would first want to find out if the person who hired me was out of his or her mind...but then I'd lock the Animation Research Library and throw away the key. I'd tear down all those Xerox copies of great animation scenes that paper too many walls (no more cribbing from The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad!). I'd tell everyone to forget they ever saw The Jungle Book..

But would the Disney suits permit such radical practices? Surely not. The priority in Burbank now is not making good films but finding new "Disney princesses" and new ways to make money from them. A Hispanic princess is surely waiting in the wings.

[Posted October 28, 2009]

From Geoffrey Hayes: Thanks for your thoughtful and well-written response. Knowing that your dissatisfaction with Disney animation goes back further than I realized actually makes more sense. I remember as a kid loving the great Disney classics and being more and more discouraged with everything post-Dalmatians. It wasn't just because they were cutting corners due to finances. The characters and the humor began to acquire a self-satisfied quality and the writing to seem very sit- com. Also, for the first time, Disney started to have the mind-set that "If this worked once, let's do it again." I can see this as the genesis of modern Disney animation, although I have found moments of purity and feeling in a lot of their features. Your advice to lock the animation archive and throw away the key surprised me, but makes perfect sense, As did your comment on Jungle Book, a film which I have always felt undeserving of the adulation it's received. I still look forward to The Princess and the Frog and hope it makes money enough to allow Disney to be a little bolder with its forthcoming features.

[Posted October 29, 2009]

From Grayson Ponti: The Princess and the Frog I think will have positive effects for Disney in the short run and negative effects for it in the long run. Fairy-tale musicals have always been picked to save Disney from hard times and have always [been] successful (that doesn't necessarily mean great) films. But this formulaic solution is more often than not destroyed by the cynical, non-innovative atmosphere the films are being made in. If Disney is going to make truly great films (Snow White and Dumbo are the two in the past that I can most easily say deserve this title) it must make something innovative with a free, creative spirit that happened in the days of the greatest cartoons by Disney and Warners. Sincerity, creativity, and emotion are essential to a truly excellent cartoon and The Princess and the Frog doesn't seem to have those qualities put into it.

[Posted October 30, 2009]

October 20, 2009:

Dining at Disney's

Here's the Disney studio's commissary in, I believe, the early 1940s. I ate frequently at the commissary in the 1990s, but usually in the cafeteria, and only a few times in the room (was it called the Coral Room?) with table service of the sort everyone is getting in the photo. I don't remember the table-service room being this large, in any case. Perhaps there's a history of the Disney commissary someplace that describes its permutations, but I haven't located it. I was around for the great makeover in 1995, but not for any other major upheavals. You can go to a much larger version of the photo by clicking on this link.

Last year Hans Perk posted a slightly different photo of the commissary, probably taken a few seconds before this one, with some identifications that I can carry over and add to, a little. I believe the balding gent in the lower right-hand corner is Ken O'Connor (who is not visible in Hans's version), and the dark-haired, mustachioed man higher in the photo who is turning to his right may be Les Clark (although, looking at the same man in Hans's photo, where he's gazing into the camera, I'm not at all sure). Hans identifies John Lounsbery at the base of the right-hand vertical pipe, and Claude Coats as looking directly at the camera in the rear center; he also sees Milt Kahl and Herb Ryman, but I'm not sure exactly which men he has identified as those two. Some of Hans's' visitors also suggested identifications, but not very many, so let's try again. If enough solid IDs turn up, I'll add an overlay like the one for my photo of the UPA staff in 1948.

As for what the Disney staffers in the photo may have been eating that day, Jenny Lerew's post on the commissary's menu provides the answers. Yum!

From John Donaldson: Starting at lower left corner, Don Towsley looks around room...at table above him, Herbert Ryman sits by waitress station...with him, backs to camera, Marc Davis and Phil Dike. Moving up, waitress completely blocks Hank Ketcham, but who can be seen in the Hans Perk photo. At back wall, center, Claude Coats, and behind him, Josh Meador. Along right edge, with hand to mouth, a very young X Atencio...at table above him, Virgil Partch. Sitting by station, John Lounsbery. At table next to X Atencio, towards us, wearing glasses, Erwin Verity, and the back of Jack Bruner.

[Posted October 21, 2009]

From Gunnar Andreassen: Your posting about Dining at Disney’s: Not the easiest task to make identifications here, but I have a few suggestions: Far left, near the window: Joe Grant, party behind a flower. Left, the man at the right—and in front of the window: Al Perkins (one of your earlier mystery men). Right, close to the window in the rear: Webb Smith, with a cigar or finger in his mouth. I agree with Frank Thomas at the right. The man you suggest is Les Clark: He does resemble him a bit, but he looks younger and with too much hair. Claude Coats is probably the man in the rear—as pointed out to you. The waiter in white jacket must be a young Sean Connery. Oops, he was probably too young in the early '40s.

From Tom Carr: This hardly looks like a place where a major labor battle was brewing— quite the opposite. The Disney commissary is a fine example of 1940s American Art Deco design, down to the little touches like flower vases on every table... something like the elegance of the railroad dining cars of the period. There's also a solid and inexpensive menu (too heavy on the meat by today's nutritional standards) with even a good selection of beers, so it doesn't seem to me that the Disney brothers were mistreating their employees. This was still the Depression era (although getting near the end of it), and this elegant dining room wasn't exactly a Salvation Army soup kitchen! So, what happened to provoke most of the staff to picket the studio? Maybe it was that having so many high-strung talents in one place turned it into a powder keg, ready to go off at any moment... which it did. If I could only go back there via time travel, there are so many artists in that room that I'd like to have lunch with, just so I could pick their brains. Especially Virgil Partch (VIP).

MB replies: I've seen it suggested that one problem was that not everyone on the staff could afford to eat at the studio restaurant, that the proletariat was forced to eat brown bread out of brown bags while the aristos dined in luxury. But of the many Disney people I spoke with about the strike, I can't recall anyone ever mentioning the commissary as a source of discontent. (The Penthouse Club was a far more conspicuous symbol of class divisions.)

[Posted October 22, 2009]

From Stephen Perry: Is that Walt sitting at the bottom right-hand corner table, wearing the neck-a-chief? Although it looks more like him in the Hans Perk photo with his head turned away from camera.

MB replies: I think it may be; and if it is, is that Bill Garity seated with him, rather than Ken O'Connor? Or is the man who is possibly Walt actually T. Hee, who wore such a neck kerchief and would more likely be seated with O'Connor? I've been flipping through my photo files, and so far I don't have an answer that satisfies me.

[Posted October 25, 2009]

From Jenny Lerew: I have to weigh in…is there any chance it could be Ted Sears? It looks like his head(and hairline) to me. Sears was a bit portlier (I think) than the other suggested men, but as all we see is, well, what we see it could still be he. Anyway, my two cents!

[Posted October 29, 2009]

October 14, 2009:

Walt the Yalie

On October 12, I posted a revised and greatly expanded version of my piece about the day—June 23, 1938—that Walt Disney received an honorary master of arts degree from Harvard University. My page includes five photos taken that day, but I had none from the previous day, June 22, when Walt received an honorary M.A. from Yale University. Now Mark Sonntag has remedied that lack with the photo above, a group photo of the recipients of Yale's honorary degrees with the university's president, which I'll also be appending to the Harvard page.

Walt is third from the left in the second row; he appears to be standing on one step lower than the other men in his row, thus leaving the impression that he was shorter than he actually was. Yale's president, Charles Seymour, is third from the right in the front row, and immediately to his left is Lord Tweedsmuir (John Buchan), the governor general of Canada. Both men received honorary degrees from Harvard the next day, as did Wendell M. Stanley of the Rockefeller Institute, who is at the far left in the front row. Thomas Mann, the great German novelist, is second from the left in the front row, and Justice Stanley Reed of the U.S. Supreme Court (a Yale alumnus who had been appointed to the court five months earlier) is at the far right in that row. Serge Koussevitzky, conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, is standing just behind Seymour and Tweedsmuir.

My friend Professor Roger Webb of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, a Yale alumnus, believes the photo was taken in front of Woodbridge Hall, the building that houses the offices of the university's president and the Yale Corporation, the university's governing body.

October 13, 2009:

Groucho, Harpo, Chico, Zeppo—and Walt?

Last year, when I was searching through 1922 issues of the Kansas City Star for traces of Walt Disney's early career, I ran across this intriguing ad in the issue of Saturday, April 8:

It was around this time that Walt Disney was getting ready to make his break from the Kansas City Film Ad Company and his sideline business, Kaycee Studios, and go into business as Laugh-O-gram Films. He certainly could have attended one of the Marxes' shows the week of April 9, and I wish I knew if he did. How pleasing it is to think of the very young Walt rubbing shoulders with the not-quite-as-young Groucho. I don't recall any mention of Walt's encountering the Marxes when everyone was working in Hollywood in later years, but caricatures of the brothers did turn up in Mickey's Gala Premiere and Mother Goose Goes Hollywood, so presumably relations were at least friendly.

And speaking of the Marxes, here's another Disney connection, in Hedda Hopper's column as it appeared in the Los Angeles Times for March 2, 1946:

Johnny Appleseed, the legendary man who went through the wild west in the old days planting apple trees, is certainly getting a play here [in Hollywood, that is]. Walt Disney's doing a cartoon fantasy based on the character. Now GrouchoMarx is cooking up a musical for Broadway about Johnny Appleseed, in which, if plans go through, he'll play the lead role straight.

My Marx Brothers library is not extensive, but Joe Adamson's Groucho, Harpo, Chico, and Sometimes Zeppo makes no mention of either "On the Balcony," the 1922 show, or Groucho's abortive (I assume) Johnny Appleseed project. Additional information would be welcome.

[An October 14, 2009, update: Thanks to Craig Dauterive, Dana Gabbard, Peter Hale, and Mark Mayerson for steering me toward a Web page about On the Balcony (and, in Mark's case, to the entry in Glenn Mitchell's Marx Brothers Encyclopedia on which the Web page is based). The show, which ran in various forms for at least a year and a half, evidently played Kansas City at least twice; a photo on the Web page is identified as having been taken in Kansas City in December 1921. So if Walt Disney didn't see On the Balcony, it wasn't for lack of opportunities.]

From Patrick Malone: It might be a stretch, but another thing that stuck out for me on that ad was mention of "The Ward Brothers." I have to wonder if Disney might have seen the show and was flashing back to this when in the 1941 short The Nifty Nineties he had a vaudeville duo named "Fred and Ward: Two Boys from Illinois." Even though the names then referred to Ward Kimball and Fred Moore, it would be a neat reference if Disney was recalling that and seeing that Kimball's name fit perfectly, he recreated the show in his cartoons.

[Posted October 14, 2009]

From Tom Carr: Something else that I find fascinating in this ad is that around the middle of the bill, there's Ben Bernie ("The Old Maestro"), apparently working as a solo act. For those who don't know, Bernie was one of the most popular dance band leaders of the 1920s and '30s, and a pioneer radio broadcaster. I believe that it was the Coon-Sanders Nighthawk Orchestra that had the first nationwide broadcast "wire," (on WGN, Chicago) but Bernie's radio show came along at roughly the same time (1924-25). Since there's no mention here of "His Orchestra," my guess is that he might have been working as a standup comic with a violin— not unlike young Benny Kublelsky was at the same time, and I hope I don't have to explain who he was!

A minor Bernie-Disney connection: in 1932, the Bernie band recorded a tune called "What, No Mickey Mouse?" I'll post it at Pilsner's Picks if anyone's interested.

[Posted October 15, 2009]

Calling All Girls!

And while we're talking about interesting old newspaper ads, here's one from the Los Angeles Times for April 28, 1946:

I never knew inking and painting cels could sound like so much fun.

October 12, 2009:

Walt at Harvard, Round Two

Last May I posted a "Day in the Life" Essay page on Walt Disney's visit to Harvard University on June 23, 1938, to receive an honorary degree. Like other "Day in the Life" pages, that one is organized around a group of photos taken on the same day, sometimes no more than minutes apart.

I've now revised and greatly expanded the original "Day in the Life" page, adding a lot of information that I picked up when I visited Harvard's archives in July, along with bits and pieces from other sources. Reading that page, as well as the earlier "Day in the Life" page on Walt's arrival in New York on June 20, 1938, will give you some sense of what Walt's life was like seventy-one years ago last summer.

On the June 23, 1938, page, for example, you can see Walt, decked out in his academic robes, getting ready to light up and then puffing away in the company of his fellow honorees, including two Nobel Prize winners. He was an addicted smoker, no doubt about it, and I've never seen better photographic evidence of his addiction.

As to why we should care what Walt was up to, way back then, part of the answer is that it was Walt Disney doing those things. For some of us, anything Walt was doing is of interest. More than that, though, Walt had a way of making himself interesting that was beyond the capabilities of a lot of other celebrities. For one thing, he gave a lot of interviews, and what he said in them was often, and obviously, what he actually thought. Our present-day celebrities, politicians especially, could learn a lot from Walt's spontaneity and honesty. I've added some pertinent quotations from Walt to the Harvard page.

Enough. If you'd like to take a short trip back to Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1938, click on this link.

October 9, 2009:

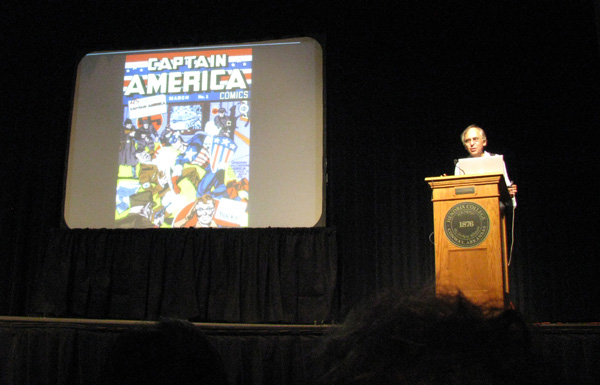

Art Spiegelman in Arkansas

That does have an oxymoronic sound, doesn't it? Art Spiegelman is nothing if not a true New Yorker, and as we all know, when true New Yorkers leave their city they start getting dizzy and disoriented about the time they reach the Vince Lombardi Service Area on the Jersey Turnpike. And as for flying to the middle of the country, well...

But Art seemed to be weathering his one-day visit to the hinterlands quite well when I saw him last Tuesday evening. He was in the Natural State to speak at Hendrix College, a small private liberal-arts school in Conway, about a half hour's drive northwest of Little Rock. He packed Staples Auditorium, which holds almost nine hundred people, with a crowd made up mostly of students but with a substantial sprinkling of elders like me. Art gave them a PowerPoint show that summarized comics (or, if you prefer, comix) theory and history, as well as Art's own history. The show ran a little long, and it could have used more of Art's gifts as a comedian—there were flashes throughout his talk of a comic sensibility that echoed Jewish New Yorkers like Woody Allen and Larry David—but it was overall a very satisfying evening.

Art's best-known work is, of course, Maus, the harrowing translation into comics form of his father's suffering and survival during the Holocaust, but the best single-volume introduction to Spiegelman may be Breakdowns, a collection of short pieces originally published in 1978 but reissued last year with a great deal of new material. Maus is the more important book, deserving of its Pulitzer Prize and all the other praise it has received, but it is also blunt and harsh, as the subject matter demands. It is perhaps in Breakdowns that you can best sense Art's fascination with the comics form and the wonderful things that can be done with it but rarely are.

Art and I have been aware of each other for many years—as he reminded me Tuesday evening, he was a reader of Funnyworld—and over the years we've exchanged emails and, more recently, phone calls as he and his wife, Françoise Mouly, put together the gorgeous book published last month as The Toon Treasury of Classic Children's Comics. But we'd never met. We made up for that after his talk, when Phyllis and I visited with him for an hour or so over a glass of wine at his hotel.

What a joy to talk with one of today's greatest cartoonists about Carl Barks and R. Crumb and other subjects of common interest. As to the substance of what we talked about...well, good conversation has a bad habit of evaporating quickly, and Tuesday evening's conversation was no exception. I do remember, though, Art's telling me that he and Françoise Mouly would share the stage with R. Crumb on November 13 at the University of Texas in Austin. Crumb and Mouly will be making several such appearances to promote Crumb's just-published illustrated version of the Book of Genesis, but Spiegelman will be with them only at Austin. I'd love to be there, too, although I probably won't be.

Speaking of that Crumb book: I've only started to read it, but so far it's extraordinary, not just in its drawing (that's to be expected with Crumb) but in its strict adherence to the biblical text. I can't help but wonder what the fundamentalists will make of it, especially since it's even clearer from Crumb's drawings than from the text itself how strange and often cruel so much of the Hebrew Bible really is. (I once read the King James Version of the Bible straight through—as anyone who fancies himself a writer probably should do, since so much of our everyday language is derived from it—and I remember that when I got to the sublime Book of Job I felt as if I were coming up for air.) I haven't seen many reviews so far, but Jeet Heer's excellent piece tells you what you most need to know about the book.

Updating Walt

Paula Sigman Lowery, formerly a Disney archivist and more recently a "creative consultant" to the new Walt Disney Family Museum (and the wife of Howard Lowery, the well-known dealer in animation artwork), has written with some clarifications and corrections to several Disney-related items I've posted here. I've included links in Paula's comments to all the items, and I've added updates within two of the items themselves.

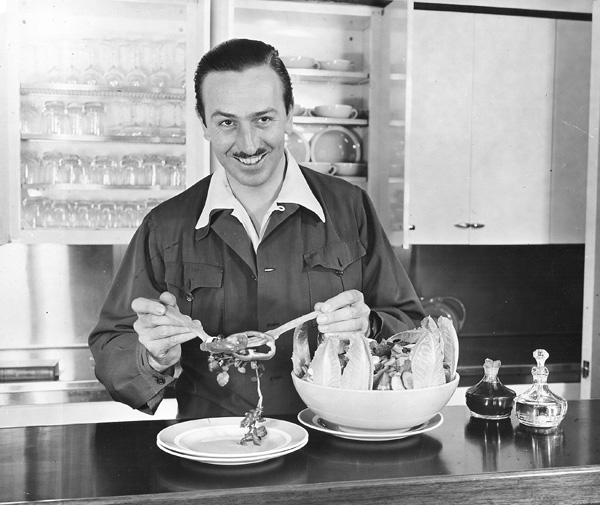

Re the photo of Walt in the kitchen, making a salad. Of course you realize that's Walt in his OFFICE kitchen, at the Disney Studio...so it's undoubtedly a publicity photo, circa 1940.

Re the Rockwell cover painting—the painting actually hung in the Archives for many years. I can probably still recite the description Dave [Smith] and I would provide to our weekly tours for new employees. It was returned to the family circa 1984, along with Walt's awards and miniature collection, which had been housed in and cared for by the Archives since its establishment in 1970.

Re the photo of Walt and the Mickey doll at the Western Union keyboard, some additional digging at the Western Union archives uncovered more clarification: Mickey was the first image transmitted by Western Union's new "facsimile" process, and was sent on the Buffalo to New York line. It was sent on Walt's birthday, December 5, 1935.

October 2, 2009:

Uh-Oh

Well, it's not at all a big deal, but a friend sent me a surreptitiously snapped photo of a wall display at the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco that includes this statement: "Reprinted newspaper comics began to appear in Mickey Mouse Magazine in 1935. These evolved into a full line of Disney comic books, which continued for decades."

Actually, reprinted Sunday comics didn't start appearing in the Mickey Mouse Magazine until the July 1937 issue, and the magazine didn't "evolve" into a comic book. Reprinted newspaper comics were never more than a minor part of its lineup until the very last issue, dated September 1940, when they suddenly took up half the pages. The first issue of Walt Disney's Comics & Stories, a true comic book, appeared the next month.

As I say, not a big deal, but I hope the carelessness visible in this small matter—how hard could it have been to get those two sentences right?—is not mirrored elsewhere in the museum.

From J. B. Kaufman: About the misstatement about Disney comics that you cited: I have to own up. That was me. (You can make this a public confession if you want.) At this point I don't remember where I got that date, but seeing that it was wrong, I'm glad you caught it. Now that we're over the major hurdle of getting the place open, there's general recognition that we're going to have to fine-tune some of the text and make changes, and obviously that's one of the parts that need to be changed.

[Posted October 4, 2009]

October 1, 2009:

He Slices! He Dices! He's Interactive!

He's Walt Disney, of course, and I wish I knew why he was in the kitchen for this photo shoot in, I'd guess, the mid- to late 1930s. Walt was not a salad kind of guy. Somewhere in my files I have a Los Angeles Times article that includes his chili recipe, and the inescapable conclusion after reading that recipe is that if cigarettes hadn't killed him, his diet was ready to finish the job.

But let's be grateful he was around for as long as he was. As every Disney devotee knows, today is the official opening day of the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco, a $110 million high-tech tribute to the man and his many accomplishments. I've linked to the museum's official web site, but its Facebook page is a richer source of information.

Just about every "Disney historian" I've ever heard of seems to have been involved in the planning for this museum, but as I've mentioned, I wasn't invited to take part in any way. I've been exchanging cordial emails with Walt's daughter Disney Disney Miller, the museum's prime mover, for several years, but perhaps when decisions were being made, someone deemed me insufficiently enthusiastic or excessively skeptical about some parts of Walt's legacy. It wouldn't be the first time.

The advantage my position gives me is that when I get around to visiting the museum, I will be able to offer you my opinion of it without feeling the slightest obligation to color that opinion to suit anyone else. Not that my opinion will count for much, but it'll be wholly my own. I'd been feeling a little tepid about scheduling a visit to museum, but now that I've realized how unusual my position will be—at least as far as "Disney historians" are concerned—I'm excited about seeing it and telling you what I think. I hope and expect to like it a lot. I'll let you know when I've firmed up my travel plans.

The museum has been getting positive reviews so far, but it's unfortunate that the New York Times's Edward Rothstein chose to praise "Neal Gabler's fine recent biography" of Walt Disney in his piece on the museum's debut. This was probably Rothstein's way of making it up to Gabler (who moves in the same journalistic-literary circles) for what the Times did in an article about the museum last spring, when it cited Diane Miller's very low, and entirely justified, opinion of Gabler's book.

The museum is of course touting Rothstein's review on its Facebook page. You gotta do what you gotta do.

From Harry McCracken: Please visit the Walt Disney Family Museum...I'm dying to know what you think.

I went this morning [October 1], and in most respects that matter, I was impressed. The sections up to the strike are far more ambitious and interesting than everything afterwards, but I guess that makes sense. In general, the museum scales its ambition to match Walt's direct involvement and interest—lots of stuff on his youth and pre-strike films, then one small room with every animated feature from the mid-1940s onwards crammed into it, then a huge section on Disneyland. It's a feast for someone like me who hasn't seen many Disney documents in person, and I'm glad I live nearby, since it's tough to take it all in during one visit.

And in case you were wondering: As far as I could tell, Bob Thomas is the only Disney biographer who made the cut in the gift shop (which inexplicably sells replica Scrappy pull toys—perhaps in tribute to Mr. Mintz). The gift shop is a disappointment in general—not radically different from one of the higher-end shops at Disney World or Disneyland, and lacking the seriousness of purpose of the best parts of the museum itself. Next time I'm in, I'll ask at the counter if they have your book. (Maybe you should orchestrate a conspiracy among Bay Area Disney fans.)

[Posted October 2, 2009]