"What's New" Archives: November 2009

November 30, 2009:

On the Sidewalk with Charlie Mintz

November 25, 2009:

November 17, 2009:

November 13, 2009:

November 5, 2009:

November 1, 2009:

On the Barricades with Art Babbitt

November 30, 2009:

On the Sidewalk with Charlie Mintz

Back on September 20, at the end of an item about the Winkler studio of the '20s—the studio that Charles Mintz and his wife, Margaret Winkler, owned, and that became Screen Gems in 1931—I wrote:

I find in my files a photo of Nat [Mintz] and more than a dozen Mintz staffers, taken in the middle 1930s on the sidewalk outside the Mintz studio on Santa Monica Boulevard. They had gathered there for some unknown reason—a fire drill, maybe? I'll forgo posting it unless some of you out there really want to see it.

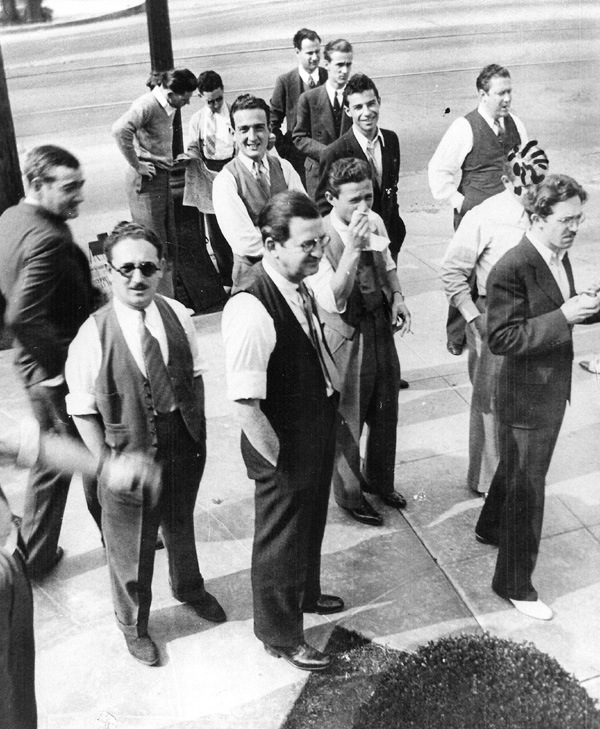

No one has asked to see that photo except Jenny Lerew, but Jenny's wishes carry more weight with me than most people's. In addition, I'm getting ready to leave town for a week, and I want to tie up this loose end. So here's the picture, and here's who's in it, the identifications provided by Ben Shenkman, who lent the photo to Milt Gray for copying.

That's Charles Mintz, with the glasses and vest, in the center; his brother Nat Mintz—who wasn't working at the studio then but happened to be visiting that day—is at the far left, turned part way toward the camera. The man between the two Mintzes is Al Rose, who directed Krazy Kat and Scrappy cartoons. Immediately to Charles Mintz's left is Jimmy Bronis, the production manager; the man with the mustache to Bronis's left is the animator Ed Rehberg. Directly behind Rehberg, his head marked with ink on the photo for reasons I don't know, is Sid Davis, also an animator. The two young men directly behind Charles Mintz and Bronis and smiling at the camera are, from the left, Dave Treffman, animator, and Irv Spector, animator. The cigar smoker to Spector's left is Eddie Kilfeather, the studio's resident composer. The four men at the rear of the photo are, from left, Herb Rothwell, George Rose, Izzy Ellis, and Rex Cox, all animators. (A few of these names are not familiar to me, and corrections of any misspellings would be welcome; ditto for any misattributions of jobs.) [A December 16 update: I've fixed the incorrect identification of Irv Spector as a story man—as his son, Paul, has pointed out, Spector was an animator at the time. I've also fixed my accidental duplication of Dave Treffman's name, and added the correct identification of Rex Cox.]

But I still can't tell you why everybody congregated on the sidewalk. A cel fire maybe?

From Paul Spector: I own several photos from that period, or moment, that Mark Mayerson graciously posted for me on his own website several years ago (although the one you've posted is not among my own). My feeling is that it was just a coffee break, as opposed to a "cel fire." BTW, my dad [Irv Spector] had yet to become a "storyman" at that point (not until after WWII); he was then an animator. You might be able to date the photo to the earlier '30s as opposed to the middle '30s, because by 1936 my dad had already moved on to Schlesinger.

[Posted December 15, 2009]

November 25, 2009:

Saint Louis

That's not the saint at the left, I should hasten to say. To see a sculpture of the man after whom the city is named, you need to go to the excellent Saint Louis Art Museum in Forest Park, where an equestrian statue of King Louis IX of France stands guard at the museum's main entrance. The statue in my picture, called "Thinker on Rock," is a 1997 work by Barry Flanagan; it's on the beautiful campus of Washington University (across the street from Forest Park), where I spent several days last week. Needless to say, the sculptural rabbit suggested cartoon associations, which is why I cranked up my iPhone camera.

That's not the saint at the left, I should hasten to say. To see a sculpture of the man after whom the city is named, you need to go to the excellent Saint Louis Art Museum in Forest Park, where an equestrian statue of King Louis IX of France stands guard at the museum's main entrance. The statue in my picture, called "Thinker on Rock," is a 1997 work by Barry Flanagan; it's on the beautiful campus of Washington University (across the street from Forest Park), where I spent several days last week. Needless to say, the sculptural rabbit suggested cartoon associations, which is why I cranked up my iPhone camera.

I was on the WU campus to talk about cartoons twice, once at Professor Gerald Early's class called "Introduction to Children's Studies" and then at a public show Saturday evening that was simultaneously part of the Saint Louis International Film Festival and WU's annual Children's Film Symposium. I talked about the Disney cartoons of the '30s in the classroom and about Hollywood cartoons in general on Saturday evening. I showed a half dozen cartoons in both venues.

Technical problems dogged us in the classroom, but the Saturday show went extremely well, with excellent (video) projection on a large screen and an enthusiastic audience dominated by adults. That adult attendance was especially important to me, because my choice of cartoons, as I made clear in my comments about them, was governed by my belief that the best Hollywood cartoons were not made for children, but for a broader audience of which children happened to be part, and not necessarily the most important part.

The cartoons I showed Saturday were Who Killed Cock Robin? (Dave Hand) and Woodland Cafe (Wilfred Jackson), from Disney, Book Revue (Bob Clampett), Fresh Airedale, and Beep Beep (both Chuck Jones), from Warner Bros., and Little Rural Riding Hood (Tex Avery) from MGM. The audience's delighted and sustained laughter during Book Revue was especially gratifying—as much as I love that cartoon, I may never before have appreciated just how funny it is—but all the cartoons were very warmly received, and in exactly the spirit I hoped for.

The great value of appearances like this is, for me, the opportunity to take a fresh look at films I may know almost too well, and to think and talk about them in new ways. This time, I not only talked about the specifically adult nature of the cartoons I'd chosen, I also addressed the inescapable racial element in the two Disney cartoons, both of which include stereotypical black characters. I made two points: there is not a trace of hatred or contempt in either cartoon, whose characters are in fact caricatures of popular black performers of the '30s (Stepin Fetchit, Cab Calloway); and to put such cartoons on the shelf would mean depriving us of everything that's unquestionably wonderful about them—which is to my mind almost everything in each cartoon—for the sake of avoiding offense to the exceptionally sensitive. Not an acceptable bargain.

My trip didn't have many other animation ingredients, although I did see a couple of foreign features and had a pleasant brief visit at a Film Festival party with Brian Hohlfeld, writer and director of some of Disney's CGI children's TV programs (and a native Saint Louisan). I also enjoyed spending time with Cliff Froehlich, who as the head of Cinema Saint Louis runs the Film Festival, and who was a Funnyworld reader in years gone by.

An absorbing exhibit at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum on the WU campus about the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II includes watercolors by Gene Sogioka, identified as a background artist at Disney. His name was new to me, but I've since learned via Google that he worked on several early features, most notably Dumbo. The exhibit runs through January 4.

And speaking of political correctness...

The Princess and the Frog opened today in New York and Los Angeles. The Los  Angeles Times was enthusiastic, the New York Times considerably less so. It'll be a few weeks before I can see the film myself. In the meantime, I'll peruse The Art of the Princess and the Frog, a review copy of which I received last week.

Angeles Times was enthusiastic, the New York Times considerably less so. It'll be a few weeks before I can see the film myself. In the meantime, I'll peruse The Art of the Princess and the Frog, a review copy of which I received last week.

Last Sunday, the Los Angeles Times anticipated the film's opening by running a piece by Neal Gabler about Walt Disney's supposed racial/religious/ethnic bigotries. It's vintage Gabler, absolving Walt of the worst of the accusations against him (rather grudgingly), but still leaving you feeling that there was something not quite right about the man. And its handling of the facts is predictably loose; Gabler writes of Walt's sending the script for Song of the South to Hattie McDaniel, ostensibly to get her comments on it, but he doesn't mention that she played a role in the film. The total effect is not quite as repulsive as Gabler's handling (in his Disney biography) of Walt's supposed involvement in a fellow polo player's death, but it's repulsive enough. (Thanks to Thad Komorowski for the link.)

From Paul Reiter: Glad you enjoyed St. Louis, I certainly enjoyed Saturday night. In fact I left with stronger impressions of most of the cartoons showed, particularly Book Revue and Fresh Airedale, two shorts that I felt were overpraised when I first saw them. I think you handled the political correctness fine, although I think that some people didn't leave with a good impression for Who Killed Cock Robin?; Fetchit will always be controversial, which is probably why it's best that cartoons (and movies) that use him be shown with care.

And speaking of the political correctness, I wouldn't be surprised if The Princess and the Frog turns out to be politically correct but dull as a result of executives rejecting and tweaking things that they fear will be politically incorrect, even when they're not. Here Disney, I think, has Pocahontas and, particularly, Aladdin (two films I know generated controversy when they were released from certain respective communities due to offensive portrayals) on their minds and wants to avoid the same results. I think it's quite clear that this is a sign not just from Disney, but from all animation studios that they will be playing it safe, not that they haven't been, but here it's even more obvious.

From Grayson Ponti: I am so tired of Neal Gabler being the standard writer about Walt Disney. Not only does he not have love or passion for the man but has created a Disney that is far from accurate, has given an offensive look at Walt, Lillian, and many of the people who worked at the studio, and has a book filled with errors. Neal Gabler and Marc Elliot (I won't even discuss how awful his book is) have supported the public's belief that Walt, a man who was an extraordinary filmmaker and innovator, was a man who was angry, odious, and cold. The fact that these books are becoming much more well-received than ones like The Animated Man shows that the Disney company and to a lesser extent the animation industry have become just businesses that don't respect artistry than the way they were when Walt Disney was alive.

MB replies: I read Gabler's Times piece twice before writing about it, and now sentences from it keep bobbing up in my mind as I realize how curious they are. Take this one: "Moreover, his later live-action films typically promoted racial tolerance, and he was much more sympathetic to Native Americans than most of his contemporaries."

Gabler could only have been referring to The Light in the Forest and Tonka, two Disney live-action features from the '50s with prominent Native American characters; no other theatrical films that Walt himself produced fit that description. Both Light and Tonka are, however, so fundamentally flawed—the endings are terribly false—that to say they "promoted racial tolerance" seems beside the point. The besetting sin of Walt's live-action features, those two most definitely included, is that they take the lazy, easy way at critical points, as if to discourage anyone from taking the films—and any ideas embedded in them—too seriously.

In this case, as in far too many others, I suspect that Gabler simply didn't bother to see the films he writes about; neither Light in the Forest nor Tonka is mentioned in his book. Was he perhaps referring not to theatrical features but to the Davy Crockett, Andy Burnett, and Daniel Boone episodes of the weekly Disney TV show, all of which included Indian characters at some point? Somehow I doubt it, although it's at least possible that the first Crockett episode was the basis for his very broad statement.

[Posted November 27, 2009]

From "Garret V": After so many rehashes, do you think a biography of Walt Disney can attain high profile status that does not cater to a politically correct viewpoint? To that end, I'm assuming that Gabler had to include some salient hot button topics, otherwise what's going to stimulate the discussion/promotion machine? ...and, what better fall-guy for the misguided Nationalists' hegemonic visions of the 20th century than that celebrated midwestern rube who concocted a monstrous EPCOT? I'm trying to conjure a bit of Richard Schickel here. I think the problem is that Walt, politically speaking, has been placed akin to Ronald Reagan and therein sharks will circle. No writer who trades in knocking out cultural books every couple years will shun his bona fides when there's fertile ground for revisionism. Sad but that's how "progressive" we've become.

[Posted November 30, 2009]

November 17, 2009:

When Fantasia Spread Out

I saw Fantasia when it was revived in 1956, and what most sticks in my memory is the shot of the Earth at the start of the Rite of Spring—the planet was distended, egg-shaped, because most of the film image had been expanded to fit the new wide theater screens. I don't remember that most of the images were so flagrantly distorted as the one of the Earth, but no doubt what I saw would be intolerable to any serious viewer today. The live action couldn't have been similarly stretched without even more grotesque results, of course, and so it wasn't, and I must have wondered at the time how that mixture of screen ratios had been achieved. Thanks to Paul Penna, who steered me toward a posting of a March 1956 International Projectionist article by Norman Wasserman, now I know. Click on the thumbnails just below to go to much larger versions of each page.

From Peter Hale: I, too, first saw Fantasia in the late 50s. (I imagine it would have been re-released in the UK six months after the US re-release.) I don't recall particularly noticing the distorted globe, but I do recall the shrinking of the screen for the live-action segments as being distinctly irritating. When it was shown again several months later, at an independent cinema showing reruns, I realised that the animation had been stretched—the earth must have been the big clue, but I remember noticing that the glowing lights of the "Ave Maria" procession were ellipses instead of circles—and felt very cheated! It was some years later that I realised that the other 4:3 Classics were now being projected, as had become normal for 35mm film, with widescreen cut-off masking the top and bottom of the frame. This meant the projectionist had to keep racking up and down if anything important was happening in these areas. (The soap in the Dwarfs' washing sequence was frequently cut off, leaving Dopey's groping around unexplained!) I don't know which offense was the worse—I just wished cinemas would show old films in their original format and be done with it. They (the cinemas) had been designed to do so, after all!

From Michael Sporn: Thanks for posting the article about the special anamorphic lenses. When I first saw Fantasia in a special rerelease in 1964 when I was a freshman in college. They used this device to go back and forth between scope and non-scope. I remember most distinctly the circular dandelion spread out to an oval. It played at only one theater in NY, the Loew's Tower East on Manhattan's upper East side. I saw the film 14 or 15 different times and had to wait on a long line each time. I tried to understand how they were able to use both lenses so quickly and could only imagine special reel changes in the projection booth. Yet, I could see when the actual reel changes took place, and it had nothing to do with anamorphic lenses. (I can probably still tell you when some of those changes took place.) It's hard to watch Fantasia in its normal version since that stretched edition is still in my head; there's always an adjustment for me to make. Of course, the true version is better.

MB replies: I saw that early-'60s reissue of Fantasia, too, at a theater in the Chicago Loop, but I don't remember being so much aware then of the "stretching" of the image, although I must have been (and I certainly remember noticing abuses of the kind Peter Hale describes when I saw other Disney reissues in the '60s and '70s). Here I'll really date myself: my first viewing of Fantasia took place in the 1940s, when my brother and I, both very young, were spending Saturdays with my grandmother in Little Rock's Hillcrest neighborhod and walking unescorted several blocks to the Prospect Theatre for the Saturday matinee. Fantasia, in the more-or-less complete (and unstretched) version released in 1946, was the feature at one of those matinees, and I remember being greatly impressed by it. Saludos Amigos was another matinee film, and I must have liked it even better, because my brother and I devoted hours to building a sort of model of Aconcagua, the menacing mountain in the Pedro-the-mail-plane segment. Too bad I don't have a photo—I can't even remember now what we used as building material, although modeling clay must have been involved.

[Posted November 23, 2009]

From John Benson: I just read your website note about the 1956 rerelease of Fantasia. That release was the first time I saw the film. Unlike you, Hale and Sporn, I was completely, almost painfully, aware of how the anamorphic lens distorted every single image. I spent the time during the anamorphic segments trying to imagine what the images would look like properly projected, and hoping that the next segment would be projected properly. The Sorcerer's Apprentice was not stretched, but I was amazed that the Dance of the Hours, with recognizable figures dancing, was stretched. It's not just that the figures are far fatter, but that anything that changes from vertical to horizontal orientation, like a raised leg, suddenly changes from short and squat to long and thin. I was well aware that CinemaScope was a new process and that Fantasia had been made much earlier, and that they were trying to "update" the film in a very cheesy way. It was obviously ruining the film and I found it outrageous. I considered that I hadn't really seen the picture.

It never crossed my mind that they might be changing the lens, either manually, as Sporn hypothesized, or mechanically as the article Penna unearthed describes. And I didn't know that there was such a thing as a variable anamorphic lens until two or three years later. I assumed that the entire print was designed to be shown anamorphically, and that the "normal" parts had been squeezed on the print so that they'd look normal when projected with an anamorphic lens.

So when I just now read the article that you posted, I was astounded. Did that mean that the dinky neighborhood theatre in West Chester, Pa., where I saw the film in 1956, had actually gotten this mechanical contraption and had a variable lens? And that all the other the theatres in the country that played this rerelease did the same? It hardly seemed possible, when doing the same thing optically would be so much easier.

I sent your link to the Wasserman article to Martin Hart, curator of the incredible website The American WideScreenMuseum, and got the following reply: "Alas that New York showing was probably one of less than half a dozen theatres that went to the trouble to present it with the mechanically operated Superscope projection lens. Ultimately Disney had Technicolor make actual Superscope prints with the image size changes on the print."

Well, that made sense! So the showing I saw was just as I assumed. Like I said, I could hardly believe that the film could have been sent into general release using the expensive and cumbersome process described in the Wasserman article. Incidentally, I had been a little surprised, too, that Hart's incredibly thorough site hadn't mentioned this mechanical process for Fantasia. Noting his mention of Superscope in his e-mail, I looked again at his site under the Superscope section and didn't find a specific reference to the mechanical device, but did find the following statement: "Superscope was used in nine RKO Technicolor productions from 1955 thru 1957, and a few re-releases of older films including a bastardized conversion of Walt Disney's Fantasia which featured the original optical Fantasound system adapted to four track magnetic stereo." (Superscope was not a filming process but basically lab hardware—see Hart's site—and of course what was being done here was all in the lab.)

Later, when Fantasia was revived after I had moved to New York, I called the theatre to find out the aspect ratio the film was being shown in. The person answering the phone didn't understand the question and had to put me on hold to ask someone else. When he came back to the phone he told me that that was confidential technical information that couldn't be released to the public! He was rather hostile and had obviously been told that anyone asking that question was a troublemaker. I divined from this conversation that it wasn't being shown in Academy ratio and didn't go see it. This was evidently not the 1964 showing mentioned by Sporn, since I recall that my conversation was with the Little Carnegie, not the Tower East.

When I finally saw Fantasia in the correct ratio with multi-track stereo it was at the Radio City Music Hall. I don't recall how I found out that they were showing it that way; I don't think it was in the ads. The Radio City showing also had no credits at all. I'm sorry I can't recall just when that was, but it was long ago, probably the 1970s.

[Posted February 19, 2010]

From Ralph Daniel: I just got around to reading the response to your original entry on the variable anamorphic lenses used in the 1956 rerelease of Fantasia. About three years ago Dave Smith told me about the article in International Projectionist, but the only place I could find the magazine was at the Georgia Tech library. Fortunatley, they are only about 25 miles away from me. I have attached my scans of the article, which appear to be slightly better than the copies you were provided.

I personally remember seeing the 1956 version at the time, and I too was surprised that they would do something like that. The fact that circular objects became oval didn't bother me nearly as much as the deformation of the characters. One thing I do remember is that the Sorceror's Apprentice section was also stretched, but not very much (I specifically remember the edges of the image moving outward from the Deems Taylor introduction, so there really was a change). I guess Mickey was far too recognizable to risk distorting him by much.

One thing I wish someone would do is write a book on The Techonology of Fantasia. Think about all of the things that would be addressed:

1. The first multi-channel feature. (Show lots of pictures of the audio equipment used in Philadelphia, along with schematics available from Marty Hart's website - when I was working at the archives I came across a photo showing Stokowski with the choir wearing robes, obviously a publicity shot since they wouldn't go to that trouble to record).

2. The devices used to film it (Schultheiss Notebook in its entirety—Howard Lowery should have published it while it was in his possession).

3. The variable anamorphic lens (OK, it's a ridiculous idea, but it was technologically innovative. I wonder if there are any photos available in the photo archives).

4. First animated feature in 70mm IMAX (Fantasia 2000). BTW, did you know they cropped the IMAX feature (or at least parts of it) to produce the wide-screen version? I know because I saw it in IMAX four times because I knew I would never be able to see it that way again. In one specific scene in the Rhapsody In Blue number, the top of the canopy for the apartment entrance says "Goldberg Arms" or maybe Hotel (gee, I wonder where they got that name?). That top part of the canopy is cropped off in the wide-screen versions (theatrical, DVD, and Blu-ray).

But since the archives are now restricted from outsiders, that won't happen, either for a print book or for a website.

MB replies: I'm sure that Ralph Daniel's conclusion is regrettably correct. Lots of good ideas will never be realized, as books or otherwise, because the Disney Archives are now sealed off from anyone who isn't working there at the company's behest.

[Posted December 31, 2010]

November 13, 2009:

DizBits

I've accumulated a variety of items related to Walt Disney, and I've decided to post them in a batch, as follows:

Walt's moviegoing habits: Alberto Natal writes: "I have a question about Walt's taste. Did he have any favorite movies that were produced outside of his studios? The only thing I remember reading about him in regards to other Hollywood movies was that if a certain picture got too intense for him, he asked the projectionist to shut it off. I can't imagine what type of movie would have that effect on him. (I was thinking The Wild Bunch, but don't think he would ever want to see that one.) I'm curious if he admired or was inspired by other Hollywood movies. Yes, I read all about his idolization of Chaplin."

An interesting question, and I realized when I read it that I didn't have a clear sense of what Walt liked in movies, apart from his own productions. He watched a lot of movies and TV shows, of course, but was it for pleasure, ever—apart from Groucho Marx's TV show You Bet Your Life—or was he mainly interested in keeping up with what was going on? (As for what he didn't like, there's that unconfirmed story about his negative reaction to Hitchcock's Psycho that I mentioned some time back.) I'm sure there's an answer tucked away in some book or magazine or newspaper article, but I can't pull it up out of my meory.

Paul Anderson's return: Through Didier Ghez and his Disney History blog comes the very good news that Paul Anderson, whose magazine Persistence of Vision was overflowing with well-researched Disney information, has recovered sufficiently from a long illness to start a new blog he calls the Disney History Institute. It automatically becomes one of my first stops in my daily trawlings through the Web.

Walt up for auction: Philippe Videcoq writes: "I thought you might be interested in the upcoming November 24 Christie’s London film memorabilia auction where I’m selling 25 Disney items including Mary Blair and Bill Peet artwork, a rare 1927 typed synopsis of Alice the Beach Nut and the famous 191-page 'Future Fantasias' folder compiled for Walt before Fantasia’s premiere by studio researcher Bob Carr. Hoping you’ll consider this worthy of mentioning on your blog." Consider it done; here's the link.

And speaking of auctions...: You may have noticed on eBay recently the auction of a mimeographed intinerary for the 1941 Disney good-will tour of South America; the copy up for auction apparently originated with the late Jack Cutting. That mimeographed itinerary may be a preliminary version of the itinerary submitted to the U.S. government in December 1941 and that is now on file at the U.S. National Archives. (The Archives version is on letter-size paper; the eBay version is on legal-size paper of the kind the Disney secretaries used for meeting transcripts.) Looking at my copy of the itinerary reminded me that it includes a bit of detail about an event on the day of Walt's return to New York aboard the Santa Clara, October 20, 1941. I didn't include that detail in an item I posted last March about what Walt did in New York after he returned from South America and before he left for California, but I've added it now. The internet makes such changes easy, so why not?

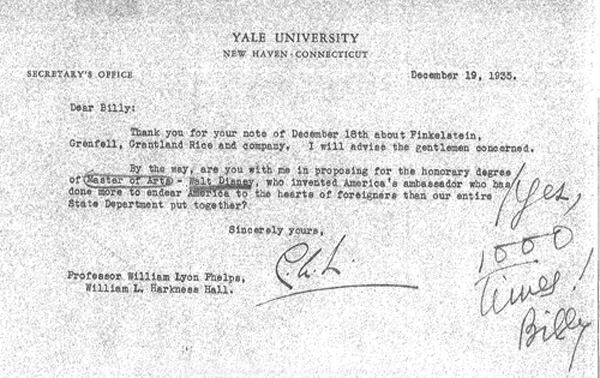

Walt the Yalie, Cont'd: Yale University's archives has provided me with copies of all of its records related to Walt Disney's honorary degree in 1938, and I'll soon update my page on Walt's honorary degrees from Yale and Harvard with reproductions of a couple of Walt's letters. The Yale records came from the files of the secretary of the university, and they show that there was active interest in giving Walt an honorary degree as early as 1935, long before Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Here's an exchange of notes between Carl Lohmann (Yale '10), the university's secretary between 1927 and 1953, and William Lyon Phelps (Yale '87), a venerable professor of English and, in those days, an imposing name in the academic world (but who was, to old friends like Lohmann, "Billy"). It was Phelps who read (and presumably wrote) the glowing citation when Walt received his honorary degree.

Meet Me in St. Louis: Phyllis and I will be driving in the direction of the Gateway Arch next week for a couple of Disney-related speaking engagements. I'll talk about Disney cartoons for Professor Gerald Early's "Introduction to Children's Studies" class at Washington University on Wednesday afternoon; then I'll speak on Hollywood cartoons in general at the 18th annual Whitaker St. Louis International Film Festival, at 7:30 p.m. Saturday, November 21. I'll be showing cartoons on both occasions, but with DVD projection and no great rarities or curiosities; I'll be offering overviews for audiences that I expect will have only the most general awareness of Hollywood animation's accomplishments.

The Saturday event, which is co-sponsored by Washington U.'s Center for the Humanities, is part of the sixth annual Children's Film Symposium, but I will, in my usual perverse manner, be pointing out that the cartoons I'm showing, like most of the best Hollywood cartoons, are accessible to children but really aren't children's films at all. The Saturday show is open to the public without charge; it'll be at Brown Hall, Room 100, on the Washington U. campus. There'll be a Q&A session afterwards. Here's a link that lists the cartoons on the program.

From Jim Korkis: While I don't know what movies Walt preferred to watch or watched frequently, he did like to check out what other studios were producing. I know that he watched To Kill a Mockingbird and turned to his son-in-law Ron Miller and said this was the type of film that he wished Disney could make but that it couldn't be released under the Disney banner because audiences wouldn't accept it.

Supposedly, that conversation was one of the reasons Ron came up with the concept of Touchstone to release "nontradtional Disney family films." Although judging by the comments I heard at the stockholders' meeting, some Disney stockholders felt that the release of Splash was the sign that Disney was forsaking everything that was Disney and was the first sign of the end of the world.

Walt did have a screening room at home (like most Hollywood producers) to watch films. I know they screened films at the studio theater as well as his home. I also know in the later years, Walt often made comments about the "down" nature of the realistic foreign films coming out of Italy and similar films that seemed to dwell on negative aspects. He also made comments about how he liked Capra films that influenced how he made some of his live- action films like Absent-Minded Professor. Wouldn't it be funny if Walt's favorite all time film was not a Disney film?

From Grayson Ponti: Walt Disney, according to Thomas and Johnston's The Illusion of Life, came to Los Angeles to be a live-action director and wanted to work at the major movie studios. So he definitely had a passion for movies and even made his animators watch movies he thought were good that weren't his own.

MB replies: I've written in The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney that there's every reason to doubt (with Roy Disney as a witness) that Walt seriously intended to go into live action when he moved to Hollywood. As I say on page 40, "the documentary record indicates that his state of mind differed from what he chose to remember, and that he always intended to go into business for himself—making cartoons." But the notion that Walt moved west with the idea of becoming a live-action director has become a part of the Disney catechism, and I'm sure we'll never be rid of it.

There's no question but that Walt and members of his staff watched a lot of movies, live action and animated. Almost always, though, the idea seems to have been that the Disney people could find ways to use what was in those films in their own work. Did Walt ever look forward to a new film by, say, John Ford or Howard Hawks or Preston Sturges or Leo McCarey because he hoped or expected to enjoy that film for its own sake? Not that I know.

[Posted November 15, 1009]

November 5, 2009:

BookBits

The Animated Man in Italian: From my translator, Marco Pellitteri, comes word that The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney has just been published in Italian. That's the cover of the Italian edition to the left; its title is Life of Walt Disney: Man, Dreamer, and Genius (a literal Italian translation of The Animated Man would not have had the same meaning, Marco has told me). I haven't yet received a copy of the book itself, but I've been impressed by how carefully Marco has proceeded with the translation, and I expect the book to be an improvement over the original American edition in a number of respects.

The Animated Man in Italian: From my translator, Marco Pellitteri, comes word that The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney has just been published in Italian. That's the cover of the Italian edition to the left; its title is Life of Walt Disney: Man, Dreamer, and Genius (a literal Italian translation of The Animated Man would not have had the same meaning, Marco has told me). I haven't yet received a copy of the book itself, but I've been impressed by how carefully Marco has proceeded with the translation, and I expect the book to be an improvement over the original American edition in a number of respects.

If you read Italian (I read only a little of that beautiful language, alas), you can learn more about the book at the publisher's Web page for Vita di Walt Disney.

I'm indebted to Giannalberto Bendazzi, himself an esteemed animation scholar (Cartoons: One Hundred Years of Cinema Animation), for bringing the book to the publisher's attention and writing an introduction for the Italian edition. It has always been a little surprising to me that, given the apparently substantial interest in American cartoons in Europe, translations like this one have been so scarce; for example, as far as I know there has never been any possibility of a translation into another language of my Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. So I'm hopeful that the Italian Animated Man is the start of a trend.

Animation Development: It may sound odd—well, actually, I'm sure it sounds odd—but when I read what David B. Levy writes, whether for his blog, Animondays, or his first book, Your Career in Animation: How to Survive and Thrive, or his new book, Animation Development: From Pitch to Production, I think of Haydn. That's because when I listen to the music of that great composer, the words that most often come to mind are "cheerful" and "sane." And that's the way David's writing strikes me. He works in and writes about a business, television animation, that leaves a lot of people frustrated and angry, and just about drives some of them crazy, and yet David's writings (and I assume David himself) never succumb to those dark urges. Living and working in New York may help him stay so even-tempered—the New York animation community strikes me as, overall, a healthier environment than the Hollywood swamp—but I'm sure David himself deserves most of the credit.

Animation Development: It may sound odd—well, actually, I'm sure it sounds odd—but when I read what David B. Levy writes, whether for his blog, Animondays, or his first book, Your Career in Animation: How to Survive and Thrive, or his new book, Animation Development: From Pitch to Production, I think of Haydn. That's because when I listen to the music of that great composer, the words that most often come to mind are "cheerful" and "sane." And that's the way David's writing strikes me. He works in and writes about a business, television animation, that leaves a lot of people frustrated and angry, and just about drives some of them crazy, and yet David's writings (and I assume David himself) never succumb to those dark urges. Living and working in New York may help him stay so even-tempered—the New York animation community strikes me as, overall, a healthier environment than the Hollywood swamp—but I'm sure David himself deserves most of the credit.

I won't pretend to have done more than sample Animation Development, since I have not the slightest interest in pitching the next SpongeBob SquarePants, but what I've read is certainly consistent with what I've read before of David Levy's work. And for an excellent review from the "inside," by someone who has gone through the process David describes, you can't beat Mark Mayerson's:

If you are interested in selling a show to television, this book is the best preparation in print that I'm aware of. If you've just toyed with the idea, this book will let you know what you're up against and perhaps persuade you that there are better ways to spend your time. ...

Levy is the eternal optimist; someone who feels that his career has been enriched by pitching and development. It has led him to some successes and to some employment opportunities on projects he didn't create, so who is to say that he is wrong? My own feeling is that any creator committed to an idea would be better off figuring out a way to develop it without interference, even if that means the idea isn't realized as animation. From my perspective, as someone who managed to get a show on the air, the compromises are too high a price to pay.

From Tom Carr: Congratulations on finding both a talented Italian translator and someone to write an introduction. My Italian is probably worse than yours, but thanks to several years of instruction in the other Romance Languages (mainly Latin and French) I can more or less follow Italian on the printed page. When it comes to actual conversation with a native Italian speaker, I'm lost.

There are so many 20th century English coinages in the idiom of animation-speak that it must be hard to find equivalents for, say, "inbetweener" or "multiplane camera," or "layout man." That last term might be good for a few off-color Italian jokes!

I happen to know one of the translators of the late William Gaddis's writings from English into German—which had to be a near-impossible task—and I'm astonished that he did so fine a job that Gaddis is probably now more popular in Germany and Switzerland than he is in the United States (where he was never very popular to begin with).

And I share your taste for Haydn...why Mozart now has the greater reputation, I'm not sure. To my ear, they're equals. Best of luck with the European sales of the book.

[Posted November 6, 2009]

RSS Mess

I hate to take up your time with such housekeeping matters, but some of you may have noticed that my RSS feeds are a bit of a mess, and that, in particular, it has become impossible to link directly from a feed entry to the relevant item on my home page. Reconciling RSS with the Dreamweaver software that I use had turned out to be much more difficult than I expected, but I hope to solve the problem, and make my RSS feed as useful as it should be, in the near future. In the meantime, if anyone has any suggestions, I'd be happy to hear them!

November 1, 2009:

On the Barricades with Art Babbitt

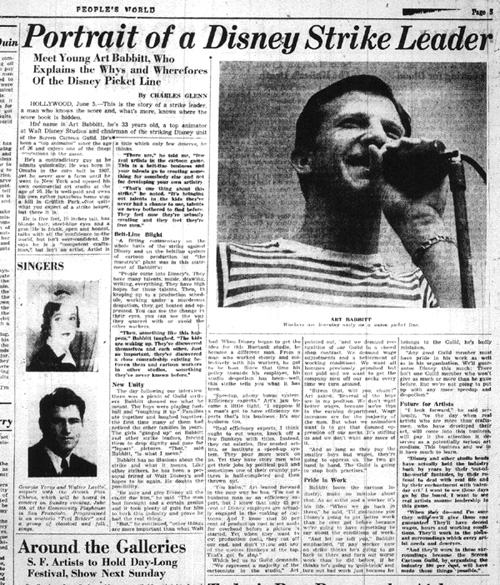

I spent a few hours recently with microfilm of the mid-1941 issues of The People's World, the Communist Party's daily newspaper on the West Coast, a companion publication to the much more notorious New York-based Daily Worker. The World covered the Disney strike in considerable detail, always, of course, from a pro-strike perspective. I'd seen some of its coverage before, in Dave Hilberman's strike scrapbook—Hilberman permitted Milt Gray to make copies from the scrapbook after Milt and I interviewed him in 1976—but other articles were new to me.

One of the most interesting World articles is this June 6, 1941, profile of Art Babbitt, the strike's official leader. Babbitt was not a communist; Dave Hilberman was, and perhaps for that reason the World did not emphasize his role (although it did run a piece about his wife). The profile is by Charles Glenn, who covered Hollywood for the World. To go to a larger and more readable version of the article, click on the version below or on this link.

I asked Babbitt about the accuracy of the quotations in Glenn's article, and he replied in a tape recording he made on October 22, 1983:

You must remember that the strike was in its infancy at that time, and I still had stars in my eyes. I learned a great, great deal after that. So that my feeling now is, speaking of both labor and management, my feeling is, a plague on both their houses. I encountered so goddamn much corruption and double talk—you name it, every kind of evil you can dream of, including an unsolicited ride that I had to Mr. Willie Bioff's house.... At Mr. Bioff's house, guess who I encountered. There was Roy Disney, Walt's brother; Gunther Lessing, who was the legal vice president of the Walt Disney studio at the time, and Bill Garity [Disney's technical chief].... Bill was decent, and honest, and as I entered Willie Bioff's house, he whispered to me, "Don't do it, Art." He meant...that if a bribe was offered, not to take it. Of course, a bribe was offered, and I did not take it....

Charles Glenn did have an axe to grind, and I do not recall using two of the words that he has used several times in his article. I don't recall using the word "despotism" and the word "oppression." I didn't encounter despotism; I found stupid management and pettiness, and certainly I was never on the rack for anything I said or felt. That was Mr. Glenn's little play with words.

If you're not familiar with the Bioff episode, I write about it on pages 171-72 of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney.

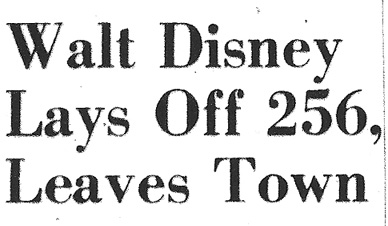

As Babbitt said, Glenn had an axe to grind, as did the World itself. Its coverage of the strike was relentlessly anti-Disney, with, in the usual Marxist fashion, scarcely a trace of humor. I had to smile, though, when I saw one headline, from August 14:

The headline linked the layoffs to Walt's departure for South America. But, well...if you were Walt, wouldn't you have wanted to get out of town, too?