"What's New" Archives: January 2009

January 29, 2009:

Hey Kids! Comics! Walt Kelly Comics!

January 28, 2009:

January 26, 2009:

At the Eshbaugh Studio, Circa 1931

January 25, 2009:

January 23, 2009:

January 19, 2009:

January 17, 2009:

January 15, 2009:

January 14, 2009:

January 12, 2009:

Still Figuring Out Where Walt Was

January 4, 2009:

January 29, 2009:

Hey Kids! Comics! Walt Kelly Comics!

As many of my readers probably know, Art Spiegelman and his wife, Françoise Mouly, have been assembling a "Toon Treasury," a collection of classic comic-book stories chosen with young children in mind. It will be a followup of sorts to their earlier "Little Lit" collections, but this time made up entirely of classic stories, as opposed to the earlier books' mixture of old and (mostly) new.

As many of my readers probably know, Art Spiegelman and his wife, Françoise Mouly, have been assembling a "Toon Treasury," a collection of classic comic-book stories chosen with young children in mind. It will be a followup of sorts to their earlier "Little Lit" collections, but this time made up entirely of classic stories, as opposed to the earlier books' mixture of old and (mostly) new.

I was one of about two dozen people interested in comic books who was asked to suggest stories and offer opinions on other people's suggestions. I didn't have the time to contribute as much to the discussion as I'd have liked, limiting myself mainly to comments on the Carl Barks, John Stanley, and Walt Kelly selections (all of which are good).

The book, which should be out next fall (from Abrams), will contain a lot more besides healthy helping of stories by those three masters. Sheldon Mayer will be well represented, for example; I can't say I feel the enthusiasm for his work that many other people do, but he certainly belongs in the book.

Many years ago, after Martin Williams and I co-edited the Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics, we proposed to the Smithsonian Institution Press a followup volume that would have been generally similar to what Art and Françoise are now putting together; it would have been called A Smithsonian Book of Children's Comics. Despite the success of Comic-Book Comics, we couldn't sell that idea. I'm glad Art and Françoise have had better luck.

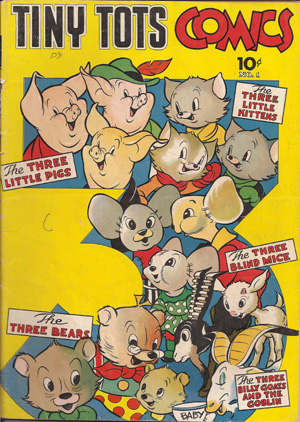

During the back-and-forth over what should go into the "Toon Treasury," I scanned a couple of early Walt Kelly stories as possibilities for the book, one from a 1944 issue of Fairy Tale Parade and the other, a version of "The Three Little Pigs," from the one and only issue of Tiny Tots Comics, in 1943. Both those comics were among the titles that Oskar Lebeck edited for Western Printing (and Dell) in New York, and like others among those titles (Raggedy Ann & Andy, Tiny Folks Funnies, Mother Goose and Nursery Rhyme Comics) they represented an effort by Lebeck, who had written and drawn children's books in the 1930s, to bring to comic books some of the qualities of traditional children's books, especially through rich and rather old-fashioned illustrations.

Kelly's drawings for "Three Little Pigs," as for the first issue of Fairy Tale Parade that he illustrated completely in 1942, are accordingly "straighter" and generally more careful than his drawings for comic books later in the '40s, although they still have the flavor of the Disney studio, where Kelly worked until 1941. His version of "Three Little Pigs" differs from the Disney version in many respects, but especially in how he depicts the wolf's fate. If you want to taste one of those bowls of boiled wolf stew on the table on the last page, you're braver than I.

To read the story, click on the comic-book cover or this link to go to the index page, and from there to individual pages. This is, by the way, my first use of the "Web Photo Gallery" feature in Photopshop Elements; if you know of ways I could improve on this first effort, let me know, since I expect to post another Kelly story here soon.

Sam Weiss

Darrell Van Citters is looking for a photo of that UPA/Bosustow/Ward artist for a book he's completing on the UPA television special Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol. I've checked my own photo files and come up dry. If you have one, please let me know, and I'll forward your messge to Darrell.

January 28, 2009:

That Mystery Guy

Robin Johnson points out a curious feature in that photo of the mystery Disney (?) artist I posted on December 16, 2008: the map visible above the desk, a map of, apparently, western Anatolia and Greece. That suggests the artist is of Greek or possibly Turkish ancestry, a supposition that is certainly consistent with his general appearance. I've been trying to think of an animation person with a Greek or Turkish name, and so far I haven't come up with one, although there must have been any number of such people in the business. Let me know if you have any ideas.

Links and Comments

I've added a permanent link at the end of each item I post on my home page, in an effort to overcome the resistance that some people seem to feel about linking to any Web site that isn't a cookie-cutter blog on the Blogger or WordPress model. Click on the permanent link for any item on this page, and you'll be taken immediately to the archived page for the month, which will be around as long as this site is around. If you want to link to something on this site, use the permanent link. Standalone pages like my reviews have always had permanent URLs.

I continue to make no provision for comments on the usual blog model, holding firm to my belief that too many such comments are worthless. When a blog posting attracts well over a hundred comments, as can happen at Cartoon Brew, it's a chore to plow through them to get to the few that are really worth reading. Often that's just a nuisance, but sometimes—as when a serious discussion of the failings of David Michaelis's Charles Schulz biography got buried in fans' clucking and fretting—it's worse than a nuisance. I'll continue to publish selected comments on a "Letters to the Editor" model, although I'll keep an eye out for some way to make commenting a little easier than it is now.

January 26, 2009:

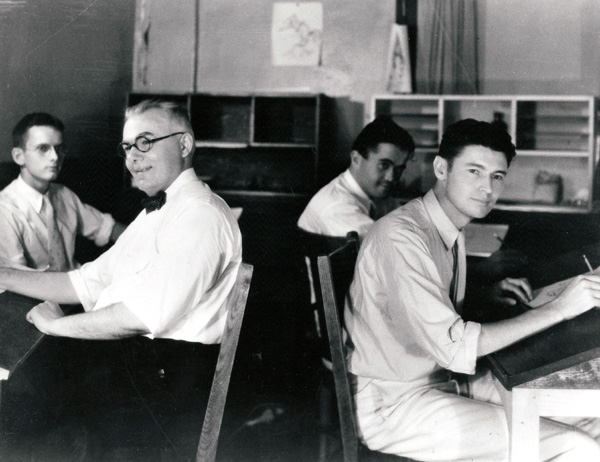

At the Eshbaugh Studio, Circa 1931

Michael Sporn has posted on his "Splog" a nifty article from the January 1932 issue of Modern Mechanix magazine (one of the many animation-related articles from that magazine available at the Modern Mechanix site) about the Ted Eshbaugh studio and its color cartoons. Eshbaugh didn't come close to making the thirteen two-color cartoons he planned—as Michael notes, Disney's move into three-color Technicolor later in 1932 sealed Eshbaugh's fate—and although he made cartoons as late as World War II, he never managed to become more than a footnote in animation history.

The article reproduces a photo of Eshbaugh and another of his animation staff, both photos quite small and overlapped by other illustrations. Here are two larger photos, lent to me by Eshbaugh's younger brother Bill Russell more than thirty years ago. (According to Russell, Eshbaugh, who was born in 1906, died in 1963.) The photo of Eshbaugh appears to be the same as the one in the magazine, but the photo of the staff is slightly different. The staff members are, from the left, Jack Zander (later a Harman-Ising and MGM animator and owner of a New York commercial animation house), Andrew "Hutch" Hutchinson, Cal Dalton (later an animator and director at Schlesinger's), and Pete Burness (later an MGM animator and director of UPA's Magoo cartoons). I marvel to think that Jack, one of animation's true good guys, was still around more than seventy-five years after these photos were taken.

January 25, 2009:

Card Check, 1941 and 2009

With a Democrat in the White House and Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress, the stage has been set for a bruising battle over the Employee Free Choice Act. That bill would permit the National Labor Relations Board to certify a union as the bargaining agent for a group of employees through a "card check." If the NLRB concluded that a majority of employees had signed valid cards authorizing a union to represent them, the employer could not hold out for a secret-ballot election but would have to accept the union.

Does that sound familiar? It should, if you know much at all about the Disney strike of 1941. The critical issue there was precisely whether Walt Disney would accept the Screen Cartoonists Guild on the basis of a card check, as the union insisted, or only after a secret ballot, as Walt insisted. Either method was then legally acceptable, but card check fell out of use after Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947. From then on, a union could still gather signatures on cards, and could still present them to an employer, just as before, and the employer could accept the union on that basis—but if the employer insisted on an election, there had to be one.

If Taft-Hartley had been in effect in 1941, there would have been an election at the Disney studio, and probably no strike. But would Walt have won such an election? And if he had won, would that have been proof that a secret ballot was, as he insisted, a better method than a card check? After all, as a management attorney wrote a few years ago, "Workers presented with a union authorization card may sign it because they do not want to offend the person before them, or they may want the union agent to just leave them alone. The workers are sometimes led to believe that they are signing something else, such as a request for a secret ballot election or a non-binding statement of interest. At other times, the workers are simply threatened into signing the card."

The problem is, as Thomas Frank wrote in the Wall Street Journal after last year's presidential election, "union-certification elections often don't met the most basic democratic requirements. Supervisors routinely hold captive-audience meetings with workers in preparation for elections; management commonly threatens to close up shop is the union wins; antiunion employees are frequently rewarded and pro-union employees are sometimes fired." All of which sounds very much like the run-up to the Disney strike, as you know if you've read about the strike in The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, and especially if you've read Walt's own belligerent remarks in a February 10, 1941, speech to a group of his employees.

As Frank—a rare sane voice in the Mad Tea Party that is the Journal's editorial pages—put it, "Card check is about power. Management has it, workers don't, and business doesn't want that to change." Walt and Roy Disney certainly didn't. They were typical entrepreneurs, their resentment of unions a byproduct of their intense identification with their company. It was "Walt Disney Productions," after all, and not "Animated Movies, Inc."

I'm reminded of an incident that the caricaturist and layout artist T. Hee recalled back in 1977, in one of the interviews that Milt Gray and I did for Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Hee spoke of seeking a raise in the 1930s from Leon Schlesinger—who as a cartoon-studio owner was not a creative entrepreneur like Walt Disney, but an entrepreneur nevertheless. When Hee asked for more money, Schlesinger said, "Come here,"

and he took me to the window and he showed me a lot of people coming up the street—they'd come back from lunch, they were coming back to work—and he said, "You see that guy there? That care of his? I bought that car. I paid for that necktie he's wearing." I didn't like that at all. He was paying that guy for his work, he wasn't buying him an automobile, or buying him a necktie.

But Schlesinger no doubt sincerely believed what he said. Walt's mind worked in much the same way. As Ward Kimball said: "No matter who you were, and what he paid you, somewhere in the back of his mind he figured he was doing you a favor because he was paying you money." In a sense he was right; as Walt was not loath to point out, it was his and Roy's sacrifices as they built their company that made many people's jobs possible. But in his entrepreneurial zeal to maintain complete control of his company, he effectively denigrated the value of the work of many his employees and denied the validity of their desire to exercise some small amount of control over their own destiny. That was the mistake for which he paid with a destructive strike, and for which we all paid with the diminished vitality of the films Walt made after that strike.

January 23, 2009:

That Reminds Me...

Oscar Bait: As everyone knows by now, WALL•E, Kung Fu Panda, and Bolt are the three nominees for best animated feature. The flurry of talk about WALL•E's being nominated for best picture came to nothing—predictably so, given that the Motion Picture Academy established the animated-feature category precisely in order to forestall another nomination, like that of Beauty and the Beast in 1992, that narrowed the nominations available to live-action filmmakers. I was cool to all three of this year's nominees when I wrote about them here, WALL•E especially; you can read my comments by clicking on the links above.

I have a borrowed Blu-Ray of WALL•E sitting on my shelf, but I haven't worked myself up to watching it again. I intend to do so, one of these days soon, but I can't say that I feel the slightest urge to see Kung Fu Panda or Bolt again. They're not terrible films, just profoundly ordinary. When I saw WALL•E, though, I thought it really was terrible, and that's why I want to see it again.

Of the shorts nominees, I've seen only Pixar's Presto, which is, like all Pixar shorts, pleasant but insubstantial, but most animated shorts that make it through the Academy's gauntlet are no better. The shorts that don't get nominated are usually more interesting than those that do, and I doubt that this year is an exception.

Despereaux Revisited: Vincent Alexander wrote in response to my January 19 comments on The Tale of Despereaux: "I haven't seen the movie, so I suppose I shouldn't judge, but I've seen the trailer and the character designs are enough to make me avoid going to see it. The mice in this film are the same kind of unpleasant mix of realism and exaggeration that made Monster House so hard to look at. The designs are photo-realistic, except for certain parts of the body being out of proportion (the heads, the ears, etc.). That seems to me to be a misunderstanding of cartoon exaggeration. The human characters in Despereaux, on the other hand, look like lifeless plastic dolls. Plus, the characters all have these strange beady eyes. They are too small, and the pupils are too big to fit in them. To me, they all look possessed. Whatever your opinion of WALL•E and Kung Fu Panda, both are far more aesthetically pleasing than this."

I agree, on all counts. Vincent also writes: "I was wondering if you're planning on seeing Coraline. Personally, I'm excited." I'm definitely planning on seeing it, even though stop motion is not my favorite form of animation. I enjoyed Henry Selick's The Nightmare Before Christmas, and I expect to enjoy Coraline (see below) considerably more than I've enjoyed any other animated feature I've seen recently.

January 19, 2009:

Well, Neau

Michael Sporn gave me a bit of a hiding the other day for my January 12 and January 15 items in which I passed along some criticisms of the computer-animated feature The Tale of Despereaux, which I hadn't then seen. Despereaux was still playing at a local theater yesterday, and so I went to see what Michael insisted was a much better film that the one that some reviewers described.

I came away thinking that Emily Bazelon's critique at slate.com—which condemned Despereaux as a film aimed at a very young audience but with inappropriately disturbing elements—was off the mark. I saw the movie in the midst of a dozen or more pre- and grade-schoolers, and I didn't detect any of the distress that Bazelon witnessed. (Maybe kids in the New York area, where Bazelon lives, are exceptionally sensitive, unlike the cynical hardcases out here in the boondocks.) The film also seemed intended for a somewhat older audience than the one Bazelon thought was the target; the marketing may thus have been more at fault than the film itself.

But I didn't care for Despereaux at all. I haven't read the book on which the film is based, but the screen story's tone is annoyingly arch, to say the least, as if it were a greatly distended Fractured Fairy Tale, and its narrator, Sigourney Weaver, an updated Edward Everett Horton. The film opens with some silly extended business about rats and soup and royals, and it seems to start all over again several times after that, as if the narrator were easily distracted from a tale that is much less than compelling.

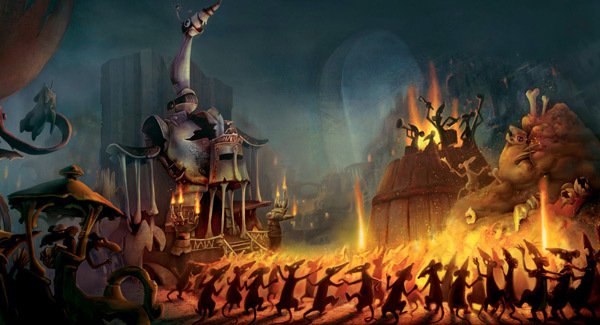

To make matters much worse, Despereaux's directors, Sam Fell and Robert Stevenhagen, present their fundamentally frivolous story in what has become standard-issue CGI. What's on the screen looks mostly quite serious, even horrific, especially the extended sequences in the dungeons of "Ratworld." There's scant evidence that the directors tried to align their fluffy story with their sober visualization of it. Instead, the computer animators just do what computer animators almost always do, which is fill the screen with photo-realistic fur and pores and freckles, punctuated by derring-do that moves freely in three-dimensional space and echoes live-action features of the Spielberg-Lucas stripe (themselves heavily dependent on CGI, of course).

To make matters much worse, Despereaux's directors, Sam Fell and Robert Stevenhagen, present their fundamentally frivolous story in what has become standard-issue CGI. What's on the screen looks mostly quite serious, even horrific, especially the extended sequences in the dungeons of "Ratworld." There's scant evidence that the directors tried to align their fluffy story with their sober visualization of it. Instead, the computer animators just do what computer animators almost always do, which is fill the screen with photo-realistic fur and pores and freckles, punctuated by derring-do that moves freely in three-dimensional space and echoes live-action features of the Spielberg-Lucas stripe (themselves heavily dependent on CGI, of course).

Some of the characters are more stylized in appearance than others, notably Princess Pea (seen above), who echoes in crude fashion the elongated statues of late Gothic art, but for the most part the story is weighed down by CGI animation's tilt toward what is both literally and figuratively superficial.

The Tale of Despereaux is, in other words, just one more of the many elaborate, expensive, and, above all, impersonal industrial products that have emerged from CGI studios over the last few years. Such animated films almost always have two directors, which seems to mean in practice that there was no real director in charge, only a couple of skillful technicians. Pixar has not fallen into the two-director trap, and as a result there has been in its films a much stronger sense of individual artists at work. The results have been questionable in many cases, as I've argued about such Pixar features as Cars and WALL•E, but the door has always been open, at least a crack, for wonderful films like Brad Bird's Incredibles and Ratatouille. I doubt there was ever a chance that The Tale of Despereaux would be nearly as good.

And on that subject... Gordon Kent has written with some pungent observations about The Tale of Despereaux, Bolt, and CGI features in general. Gordon says in part:

For me animation has always been about fantasy. It's about being transported to a world that I know doesn't exist and yet I believe in it. I believe an elephant can fly when I watch Dumbo soar with the crows. I believe in Never Never Land. I believe that a wooden doll is alive and doesn't need strings to move.

CGI seeks to replicate the world. To make a fantasy seem real. And in so doing it takes away both the fantasy and the reality. CGI attempts to ground its characters and make them seem as if they actually exist. And yet I believe the animated Dumbo can fly while I don't believe that the new CGI Dumbo they use in commercials is really flying.

When I watched Bolt it all crystalized. This is a movie that isn't really bad, per se, but it isn't engaging. And I think what separated me from believing in the movie was the CGI. I think this movie could have been a darn sight more charming had it been hand drawn. The story would have still had problems, but I'm pretty sure the characters would have been more endearing and I would have cared about them more. The act of dulling everything down in art direction with CGI was enough to make me a viewer instead of a participant. I just didn't care.

You can read all of Gordon's message by clicking on this link, which will take you to the page devoted to feedback about computer-animated features.

January 17, 2009:

On Board the Santa Clara

The evidence now seems overwhelming that the two shipboard photos of Walt Disney that I posted on January 4 were taken on the Santa Clara in 1941, when Walt and his wife were returning from South America, as John Donaldson has proposed, and not on the Queen Elizabeth in 1946, as I originally thought. Gunnar Andreassen writes:

I think John Donaldson must be right in assuming that Walt and Lillian were on board the Santa Clara. The sweater seems to me rather strong evidence, and I would think it very unlikely that he was wearing it five years later—even if the war had intervened. What troubled me was that the deck Walt is standing on seemed to be too close to the surface of the sea for it to belong to the Queen Elizabeth. She was the world's largest ocean liner in 1946—83,673 gross tons—whereas the Santa Clara was only 8,195. The railing that Walt is leaning on doesn't seem to be from the Queen Elizabeth. I have checked a lot of photos on the 'net and not found one of the Queen with the same railing.

John Donaldson weighs in with this additional evidence:

Joe Heppner, of Metropolitan Photo Service, was hired by Hal Horne to photograph Walt, from March to November, 1941... [Both shipboard photos of Walt bear a Metropolitan Photo Service stamp.]

I am sending another picture from South America, to show that the sweater striping, the front, is the same...as well as a deck photo of the Queen Elizabeth, in 1946, to show how that differs...

Just as an interesting side note, the Santa Clara was renamed the Susan B. Anthony when commissioned in World War II...sinking after striking a mine, off Omaha Beach, during the D-Day invasion...and there is where she be...

Thanks to John and Gunnar and everyone else who helped to solve this little puzzle.

January 15, 2009:

Scary Cartoons

Andrew Osmond wrote in response to my January 12 item about The Tale of Despereaux and Emily Bazelon's complaint, in a piece for slate.com, that that computer-animated film was too frightening for small children:

I reviewed Tale of Despereaux and concluded, "While the film has been given a 'U' certificate by the BBFC, parents should be warned that it's certainly capable of upsetting young children. After all, the villains kidnap a princess in order to feed her to rats, while there's also the fate of a strange magic character made out of vegetables… At the film's climax, the creature "dies" a noble death, causing one little boy at the preview screening to have a tantrum about the "poor broke vegetable."

However, I'm sceptical about if animated movies are any more disturbing to young children than they were in their earliest days. In Snow White alone, you have the Queen turning into a witch in a scene out of a Universal horror movie; the same witch toppling to her doom from a cliff; Snow White being threatened with a knife, then racing terrified through a nightmarish wood, etc, etc. I grant that some kids may be blasé about, say, Bambi's mother dying, while also being terribly upset by the villain's comeuppance in Despereaux. However, I'd be surprised if other kids didn’t have the reverse reaction. For my money, some of the imagery in Dumbo's pink elephant dream, especially when it goes wild at the end, is more disturbing than anything in Cars.

(By the way, I thought Despereaux's look was "distinctive and effective" with an emphasis on colours, textures and light. Overall, I found the film "earnest and unusual by cartoon standards, but it's also tonally confused, poorly structured and its preaching is dreary.")

The difference, I think, is that Snow White and Bambi, unlike The Tale of Despereaux, were neither conceived nor presented as films for an audience made up of very young children (and their parents). I have been told I was carried screaming from the theater during the forest fire in Bambi at age two, but my reaction didn't invalidate the pleasure that older children and adults took in the film. But if a film offers little or no pleasure to older viewers, but scares the wits out of the youngest ones, where's the justification for that?

Part of the problem, as Bazelon writes, is that the MPAA rating system really isn't very helpful. "Rubi-kun" wrote to me to poke at that lingering sore spot:

I'm still trying to figure out how Ice Age's PG for "mild peril" is any worse than all the content in Disney's Hunchback of Notre Dame [that got] away with a G. The MPAA never made much sense, but it seems as if they've been making even less sense as of late. Prince Caspian got a PG while containing tons of dramatic dismemberment and violence (but with no bleeding) and Marley and Me also managed a PG while containing quite a bit of sex talk. The next Harry Potter movie, if faithful to the book, will contain an assisted suicide, zombie attacks, and a spell that causes massive injury and blood splatter, yet it seems to have gotten a PG, even as the past two Potter movies with similar levels of violence got PG-13 ratings. Meanwhile, Slumdog Millionaire, a movie which implies acts of terror and violence but has enough restraint not to show many details, got an R rating, despite the PG-13-rated Dark Knight containing similarly intense violence. Essentially, it seems that they just do whatever the studio wishes, and if the studio's a smaller independent, slap on an R regardless.

Scary Webcomix

From Larry Latham, whose great-looking internet comics pages I wrote about last October: "The first pages of the second issue of my webcomic, Lovecraft is Missing, went up this morning. The response has been, and I say this without hyperbole, enthusiastic. Several good reviews, a judicious bit of advertising, and traffic is up to over 6,000 visits a day, with over 100,000 page views in just the last two days. Book 1 is still up, of course. The first issue was mostly set-up; the story really starts to roll in issue 2."

The Mystery Man, Again

I've asked a couple of times about the young man in this photo, with no results. In paging through Disney books in search of his face, it suddenly occurred to me that there is one member of Joe Grant's model department who isn't visible (except in comic blackface, in one group photo) in any of the photos from that department: Campbell Grant. Does anyone know if he is the mystery man?

January 14, 2009:

Walt's Whereabouts, No. 4A

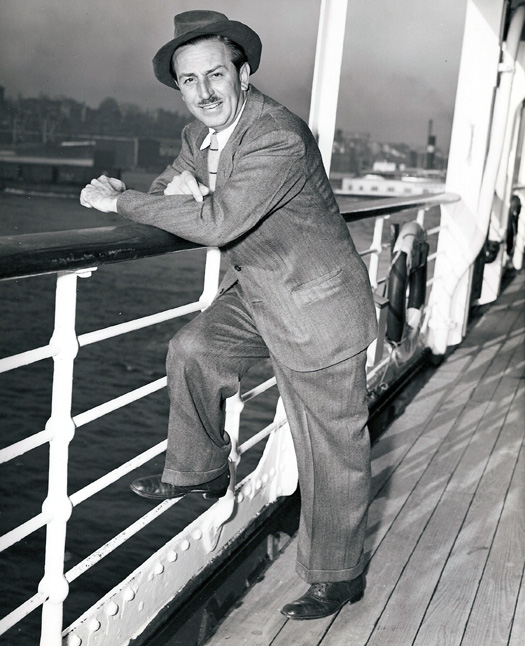

On January 4, I posted a couple of photos of Walt and Lillian Disney aboard an ocean liner, apparently taken when the Disneys were arriving at or departing from a large city. I speculated that the photos were taken when the Disneys visited England in November 1946, and I remarked, "I'm not sure yet which ship the Disneys were on when they crossed the Atlantic to England, but they returned on the Queen Elizabeth, arriving in New York on December 12, 1946."

As Gunnar Andreassen has gently reminded me, The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney includes a photo whose caption says, correctly, that the Disneys arrived in England that autumn on the Queen Elizabeth. The British incoming passenger lists from the '40s are now online, at ancestry.com, and they show that the Disneys arrived at Southampton on that luxury liner on Tuesday, November 19, 1946.

As the New York Times reported, they had left New York five days earlier, on November 14, in the company of 2,256 fellow passengers. That voyage was only the second crossing to Southampton by the Queen Elizabeth as a commercial vessel; she had been pressed into service as a troop ship in 1940 before she had made even one voyage as a civilian ship. She was re-converted to civilian use after the war and first docked in New York on October 21, 1946.

From Southampton, Walt and Lillian went on to stay at the Savoy Hotel in London, where the frontispiece photo in The Animated Man was taken. Perce Pearce, who was later to produce Walt's British-based live-action features, and his wife, June, arrived in England on the Queen Elizabeth with the Disneys. They returned to the U.S. with Walt and Lillian on that same ship, leaving Southampton on December 7 and arriving in New York on December 12. (Thanks to David Lesjak for alerting me that the British outgoing passenger lists are now available at findmypast.com.) By the time they sailed, the Disneys and Pearces had been in England and Ireland for eighteen days; I don't know how much time they spent in each country.

(Curiously, the records of the Disneys' and Pearces' arrival in England didn't turn up in an ancestry.com search. I found them only by running a general search for the Queen Elizabeth's November 19 passenger list and then going through all the pages listing non-British passengers.)

There's still the question of when and where the photos were taken, and, in particular, whether they were even taken on board the Queen Elizabeth in 1946. John Donaldson has suggested that they were actually taken when the Disneys were returning to New York from South America on the Santa Clara in October 1941. He offers this photo of Walt in Rio de Janeiro in 1941 as evidence, noting that Walt appears to be wearing the same sweater as in the two shipboard photos:

John suggests, too, that Walt and Lillian can be seen wearing their shipboard-photo clothes in the two films that grew out of the 1941 South American trip, South of the Border with Disney and Saludos Amigos. I haven't yet looked at those films again, but most likely I'll agree with John. The Disneys could have been wearing some of the same clothes five years later—especially considering that World War II had intervened—but that would be at least a little surprising. Their clothes in that 1946 photo in The Animated Man, which shows them on the sun deck of the Queen Elizabeth, differ from the clothes they're wearing in the two shipboard photos I posted on January 4.

It seems increasingly likely that the waterfront behind Walt is in New York or its vicinity, especially since both photos bear a "Metropolitan Photo Service, New York City" stamp on the back. Probably the Disneys were photographed by a professional who came aboard shortly before their ship docked in New York, to take pictures of celebrities.

But the floor is still open as to whether the photos were taken in 1941 (as now seems likely) or 1946. If, like me, you are odd enough to find irresistible enjoyment in Walt-related minutiae of this kind, let me know what you think.

Thanks to Robin Johnson for valuable contributions to this ongoing discussion.

January 12, 2009:

Still Figuring Out Where Walt Was

Family obligations have kept me away from the computer for most of the past week, but several people have come forward with information pertinent to the ongoing question of when and where Walt Disney and his wife were on board the ship seen in the photos accompanying my January 4 item. More later this week. As always, following in Walt's footsteps is great fun, for me and at least a few of my visitors, anyway.

Despereaution

I haven't seen The Tale of Despereaux, and I haven't planned to, since it's so obviously a kiddie movie (and, to judge from the trailers and stills, a rather ugly one to boot). It has been the subject, though, of an exceptionally interesting piece at slate.com, where Emily Bazelon has taken it to task for being a kiddie movie that botches the job:

Why, given this likely audience, did the moviemakers feel the need to include extended sequences with fear-pumping music; a giant menacing cat that charges after Despereaux in a gladiator ring; and Botticelli, the torture-obsessed leader of Rat World? And what's the point of a G rating if movies like Despereaux fall into that category? This movie confirms my feeling that it's past time to replace G with better age-tailored guidance. I remember sad G-rated kids' movies from childhood: Disney classics like Pinocchio, Dumbo, and Bambi. But my kids didn't find Bambi distressing. Instead, what's hard for them to handle are new movies, ostensibly created for their age group, from which they emerge metaphorically dripping in sweat, wrung out by an hour and a half of suspense and overexcitement.

Bazelon pins much of the blame on computer animation, because of the way it compresses the aesthetic distance between film and viewer that usually takes the sting out of the violence in traditionally animated cartoons:

When Road Runner sends Coyote hurtling off a cliff, kids generally shrug off the calamity because they understand that the cartoon is all an utter fake, played for humor. Despereaux, by contrast, has the kind of Shrek-like animation that left [her 5-year-old son] Simon and [his friend] Charlotte debating, in their after-movie analysis, whether the rats and mice were real. Simon thought maybe they were, because the eyes and claws looked lifelike. Charlotte thought not, but she wasn't completely sure, and, in any case, she found the head of Ratworld really creepy. When the animals (and people) are animated with such technical skill that they look like they could come to life, some kids lose their tolerance for watching them hurt each other.

Bazelon's complaint about Despereaux is a miniature version of a larger complaint that many people have about contemporary live-action movies, that in them the pleasurable excitement and suspense that many of us remember from movies made in the years before Bonnie and Clyde has been displaced by a much more intense, and much less pleasant, apprehension. Filmmakers no longer observe any restraints in what they show us on the screen, and technical advances have made it possible for them to show us almost anything they wish; that's why staying home and watching Bambi again on DVD is often the most sensible course of action.

Thanks to Bill Benzon for the link.

January 4, 2009:

Where's Walt, No. 4A

Almost a year ago, on January 30, 2008, I posted this photo of Walt and Lillian Disney on shipboard, accompanied by this speculation about when and where the photo might have been taken:

Here's yet another intriguing photo of Walt Disney (love that hat!), this time with his wife, Lillian, and apparently on board a ship. The date and place are uncertain, but given how old the Disneys appear to be, and their winter-weight clothing, I'd guess this photo is from November or December 1946, when Walt made his first postwar trip to England and Ireland. (The suit may be the one he's wearing in the frontispiece to The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney.) I'm not sure yet which ship the Disneys were on when they crossed the Atlantic to England, but they returned on the Queen Elizabeth, arriving in New York on December 12, 1946.

I was never able to pin down the date and circumstances of the photo, but now I've turned up another photo of Walt, almost certainly taken on the same day and on the same ship, and this time with a shoreline visible behind him, along with a life preserver with tantalizingly almost-legible lettering. Here it is; if you recognize anything in the photo other than Walt himself, let me know.

Mystery Solved?

I noted on January 17, 2008, that my Disney biography, The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, had come under furious attack by an amazon.com reviewer identifying herself as Patricia Block. She evidently posted the same review at bn.com, and her negative comments subsequently spread around the Web, mainly via sites that borrow from amazon. As I said in a response on amazon's page for my book, I couldn't quarrel with Block's dislike of it, but I was baffled by an alleged direct quotation from The Animated Man that I didn't recognize and couldn't locate: "everything Walt touched was worse for the attention he gave it." Where did those words come from?

Thanks to Larry Varblow, that little mystery may finally have been solved. Larry writes:

This may be old news by now, but in case you haven’t identified the mystery excerpt behind your errant online reviewer’s allegations, I may have found it. On page 283 of the paperback edition of The Animated Man you state: “Everywhere that Disney’s hand is most evident, as in some of the casting and incidental 'business,' Mary Poppins suffers from debilitating weaknesses.” Granted it would take a bit of extrapolation to get from the above statement to her comment, but perhaps your reviewer is an extreme Poppins fan (or hagiographic Walt fan) for whom it might not be a stretch.

That makes sense. I'd guess that Block relied on memory when she "quoted" from the book, thereby transforming a specific criticism of Walt's work on one film into a wholesale denunciation of the man. Maybe she misquoted me because she couldn't find that passage when she went looking for it; or maybe she didn't want to find it.

Larry Varblow is, by the way, a member of the dedicated crew that opens Walt's Barn in Griffith Park in Los Angeles to the public on the third Sunday of each month. The barn, pictured at right, is the structure that stood in Walt's backyard in Holmby Hills for many years and served as the control center for his miniature railroad, and also as his workshop.

Larry Varblow is, by the way, a member of the dedicated crew that opens Walt's Barn in Griffith Park in Los Angeles to the public on the third Sunday of each month. The barn, pictured at right, is the structure that stood in Walt's backyard in Holmby Hills for many years and served as the control center for his miniature railroad, and also as his workshop.

If you're any sort of Disney fan, and especially if you enjoy seeing things and places that give you a stronger sense of Walt as a person, a visit to Walt's Barn is a must. I spent part of an afternoon there in 2005, when I was in L.A. for several weeks doing research for The Animated Man, and I'm looking forward to a return visit. Directions and other details at this link. It is, as Larry says, the only free Disney attraction in the world.

Mystery Not Solved

To my amazement, no one has yet come forward with a firm identification for the young artist whose photo I posted on December 16, 2008. Steve Sherman suggested that the photo might be of Tony Pastor, but that seems unlikely. So I'm still waiting for the answer, which when it comes will no doubt be both obvious and totally unexpected.