"What's New" Archives: February 2009

February 28, 2009:

Coraline Revisited: 3-D, Color, and Selick

February 24, 2009:

February 23, 2009:

February 22, 2009:

The First Disney Annual Report

February 13, 2009:

February 12, 2009:

February 11, 2009:

February 7, 2009:

Hyperion Avenue at Griffith Park Boulevard, 1927

February 28, 2009:

Give 'Em the Hooks, Cont'd

My February 23 post "Give 'Em the Hooks!" about animation acting and related subjects elicited a number of comments, mostly from people who were moved by Milt Gray's anecdote about the sad last days of Bill Tytla. But I also heard from the filmmaker Ray Kosarin, whose comments seem to me to be right on target:

Your post hits on a hugely important issue, and also problem, with the way character animation is too often approached and discussed. As with so many things, hype has now overshadowed the vitally more important substance of what it's about.

For anyone to declare acting in animation the exclusive turf either of a trained animator or of a trained actor needlessly fans the fire and misses the point. Good character animation calls on many diverse skills and disciplines including (but by no means limited to) acting, drawing, staging, design, and timing. That said, no combination of these can remotely guarantee a decent or compelling performance. Good animation acting is like Justice Stevens’s famous definition of obscenity: “I know it when I see it.”

The most indispensable skill is, in fact, the most abstract, and likely the least teachable: authenticity. I'd be hard-pressed to think of many animators whose sheer draughtsmanship approaches the quality of the drawing in, say, a Don Bluth feature. Yet despite the intricately rendered anatomy and immaculate cleanup, the acting, such as it is, in these features is hopelessly hamfisted and clichéd—unconvincing and, at worst, insulting to a viewer of any age. On the other hand, we could hardly wish for a more convincing animation performance than almost any Pluto scene animated by Norm Ferguson. Even as we can see the slipshod articulation in much of the drawing, and volumes that swell and shrink as the character moves, we nonetheless do not stop believing in him for an instant.

As with any sort of acting, a performer who believes in the character, and who has command enough of whichever skills he or she brings to each performance to synthesize them interestingly and believably, is essential. A dedicated animator will be happy to learn from a traditional actor, another animator, a painter, a dancer, or a writer: in short, anyone at all with something worthy to teach.

Coraline Revisited: 3-D, Color, and Selick

3-D and Color: Michael Sporn, who hadn't yet seen Coraline at the time of his post, remarked: "I would prefer not seeing it in 3D (polarized glasses HAVE to grey/green down the image, and I’d prefer seeing actual colors on the screen, despite the 3D effect)."

3-D and Color: Michael Sporn, who hadn't yet seen Coraline at the time of his post, remarked: "I would prefer not seeing it in 3D (polarized glasses HAVE to grey/green down the image, and I’d prefer seeing actual colors on the screen, despite the 3D effect)."

As I mentioned on February 23, I saw Coraline in 3-D, and I was aware then, as in other cases, of what Michael calls the "greying/greening down" of the image. Each time, my eyes have adjusted quickly. I've seen at least a half dozen 3-D animated films in the last few years (including the wonderful prologue to the Radio City Music Hall Christmas show in 2005), and I can't recall one where the color change seemed more important than the illusion of depth.

I wonder, too: Are filmmakers taking that color change into account? That is, are the colors we see in 3-D what Michael calls the "actual" colors, and the colors in the 2-D version thus a distortion?

I've never been quite as picky about film color as a lot of people I know, because it has always seemed obvious to me that a great many things can affect a film's color before it winds up on the screen, no matter how skilled and conscientious the people involved. Accordingly, I think in terms of a range of acceptable color, rather than a single absolutely perfect screen image. Even back in the hallowed days of three-strip Technicolor, a cartoon's colors had to be chosen with an eye toward the distortions the Technicolor camera would introduce. That's why contemporary "restorations" that attempt to match the color in surviving artwork can go badly wrong; the people who painted those backgrounds or chose the colors for those cels knew that their work would look different on the screen, and they planned accordingly.

There's a lot of grumbling and griping about 3-D on the Web these days—it's rather like listening to my 85-year-old father-in-law mutter about TV's digital conversion—but I have not yet had, with contemporary 3-D, a disagreeable experience of the kind Amid Amidi recently described at Cartoon Brew. I'm old enough to remember the 3-D craze of the early 1950s, and I have no fond memories of wearing cardboard glasses or having tobacco juice spit in my face while I was watching The Charge at Feather River. Today's 3-D technology seems to me vastly better, and CGI and stop-motion animation are uniquely well suited to take advantage of its capabilities. I'm actually looking forward to seeing Monsters vs. Aliens and Up in 3-D, even though I would otherwise be approaching both films warily, given their pedigrees.

Selick: Karl Cohen's most recent newsletter for ASIFA-San Francisco—not available on the Web, unfortunately, at least not yet—includes extensive quotations from Coraline's screenwriter and director, Henry Selick, some of them addressing his use of 3-D:

Selick: Karl Cohen's most recent newsletter for ASIFA-San Francisco—not available on the Web, unfortunately, at least not yet—includes extensive quotations from Coraline's screenwriter and director, Henry Selick, some of them addressing his use of 3-D:

One of the subjects Henry likes to talk about is his use of stereoscopic 3-D. The film is made with a process called RealD and the viewer wears comfortable polarized glasses. Henry says, “Not only does 3-D capture the fact that all this stuff is real, it sucks the audience in as Coraline is sucked into this world of an alternate reality. As you watch the film you may notice there are not a lot of things that are coming out at you, it mainly is like Coraline going into that tunnel; you are going into that world.”

“It’s more 3-D in the ‘other world’ than the real world. The two worlds are actually designed differently. We made duplicate sets. The living room sets look the same, but in the real world the living room has a crushed perspective with very little actual depth to it. The floors are raked. We don’t show they are raked, but you get a sense that it feels more confining. In the kitchen it’s almost claustrophobic. In the ‘other world’ it seems to be the same living room, still very neat, but more spacious. It’s not obvious, it doesn’t hit you over the head, but before the magic happens in the ‘other world’ it is a way to make it feel better, like you can really breathe in that other place.”

“There are many differences between the two worlds. I tried not to be too blatant. In the real world we used longer lenses. I was trying to flatten space with less depth of field. The ‘other world’ was much more about wide-angle lenses. It is more pleasing in many ways, and then we amp them up till there was a certain amount of distortion. The lighting was much more naturalistic in the real world and the ‘other world’ is much more about beauty and warmth. By the end of the film in the real world the lighting has shifted slightly. It has more warmth.” ...

This is the first stop-motion feature to be filmed in 3-D (In Tune with Tomorrow, a stop-motion 3-D short, was made for the 1939 NY World’s Fair). Each digital frame of the film was shot with a single lens reflex camera. Each image was shot twice to get the 3-D effect. For each shot a special rig moved the camera slightly to simulate the distance between the left and right eye that gives us a stereoscopic effect. It also made adjustments for the distance between the camera and subject being photographed. The rigs used were adopted from robot cameras used in factories to inspect machined parts.

There's nothing from Selick about the polarized glasses' effect on the film's color, but I suspect filmmakers will be addressing that subject publicly with increasing frequency. There's a very nice short audio clip of Selick talking about Coraline at this New York Times link.

February 24, 2009:

Drink Up!

Like many another old cove, I like to end the workday by drinking a cocktail and visiting with the missus about the events in our lives. I've long enjoyed Eric Felten's weekly Wall Street Journal column, "How's Your Drink?," a delightful mix of cocktail history and recipes, many of them more than a little odd. (My own very conventional tastes run toward vodka martinis, single-malt scotch, and Americanos.)

Like many another old cove, I like to end the workday by drinking a cocktail and visiting with the missus about the events in our lives. I've long enjoyed Eric Felten's weekly Wall Street Journal column, "How's Your Drink?," a delightful mix of cocktail history and recipes, many of them more than a little odd. (My own very conventional tastes run toward vodka martinis, single-malt scotch, and Americanos.)

Felten devoted last weekend's column to deliberately ridiculous cocktail recipes from movies and TV, including an almost-plausible recipe from The Simpsons for "Flanders Planters Punch." He also wrote at length about the barroom scene in a 1951 Looney Tune, Chuck Jones's Drip-along Daffy (with no mention of Jones or Mike Maltese, unfortunately), and offered recaps of silly-cocktail moments from a few live-action comedies. It's too bad that Felten didn't make his column entirely animation-oriented, as he easily could have, given how many barroom scenes there are in cartoons—and, for that matter, how many important animation people (Bill Peet, Fred Moore, et al.) have fallen under the sway of the bottle.

Walt Disney himself lifted many a glass, not always with the happiest results, although his capacity was impressive. As Harrison "Buzz" Price, who helped Walt find the right spot for Disneyland, told me, "I think he was meaner than hell when he had five scotches, but who isn’t?" Me, I'd be comatose after five scotches, but then, Walt was a better man than me in many ways.

To read the Felten column, "Some Cocktails Are Supposed to Taste Funny," click on this link.

February 23, 2009:

Give 'Em the Hooks!

Once or twice a week I troll through my RSS feeds of animation blogs, gradually surrendering to claustrophobia as I glance at the tracings of old comic-book covers and the exquisitely rendered portraits of wretched Hanna-Barbera characters. Every once in a while, though, I see something that makes me snap to attention. This time it was when an animator announced that she was writing a book, her second. Her description of it included this passage:

I'm going to cover stuff that most other books leave out. I will show how to ACT in animation, not merely produce animation exercises. And no, it won't involve setting up a video camera...how can you possibly do this if your character is part fish, or is a tiny machine, or is a group of quarrelling octopi? The only other book on 'animated acting' wasn't written by an animator. I aim to correct this omission.

She could only be talking about Ed Hooks and his book Acting for Animation: A Complete Guide to Performance Animation (although Ed has actually written a second book about animated acting—I haven't seen it—called Acting in Animation: A Look at 12 Films). I've read Ed's book and a lot of his other writings, and I've posted some of his comments here, about The Iron Giant and Ratatouille. We disagree on a lot of things, but I find Ed to be one of the more stimulating and interesting commentators on current theatrical animation. He's not an animator, but he has acted professionally, has taught acting for years, and has clearly immersed himself in his subject.

Does the animator-author have a background that is in any way similar? Has she performed on the stage, or anywhere else? Not that I can tell. Has she read Stanislavski or Boleslavsky or Uta Hagen, or even Michael Caine's wonderful little book? Somehow I doubt it. Her clear implication is that simply being an animator gives her the authority to write about animated acting, and that such authority is lacking if someone's background is in acting itself, rather than animation.

How curious. What we have here, I'm pretty sure, is some of the residue of decades of Frank and Ollie, of Chuck Jones, of Dick Williams, and of others I could name. Decades of self-congratulation, that is, usually masquerading as humility ("animation is a gift word"), whose ultimate effect has been to seal any number of animators into cocoons of smugness: I am an animator; therefore no one outside animation has anything to say to me.

It's hard to square such smugness with the reality that speaks from most cartoons of the traditional hand-drawn kind. Animation has always been a craft open to people of only modest talents, a craft whose most important rules (Preston Blair's books are the best summary) could be learned and put into practice, acceptably if not brilliantly, in a relatively short period of time. Some animators have brought to their work great artistry, but even their work could rise to the level of art—that is, to a level where something like smugness might be understandable, if hardly admirable—only when it was a vital element in a film that was itself a work of art.

It's hard to square such smugness with the reality that speaks from most cartoons of the traditional hand-drawn kind. Animation has always been a craft open to people of only modest talents, a craft whose most important rules (Preston Blair's books are the best summary) could be learned and put into practice, acceptably if not brilliantly, in a relatively short period of time. Some animators have brought to their work great artistry, but even their work could rise to the level of art—that is, to a level where something like smugness might be understandable, if hardly admirable—only when it was a vital element in a film that was itself a work of art.

Bill Tytla (shown here) was, for my money, the greatest animator ever. I think he would understand what I'm saying here. I'm haunted by Milt Gray's anecdote about his encounter with Tytla, a little more than a year before Tytla's death in December 1968. Milt and Tytla were both working for Hanna-Barbera, Milt as a very young man learning his craft, Tytla as a much older man, his Disney years a quarter-century in the past. Tytla was so broken physically and mentally that he had no choice but to take the bus to and from work. I've often wished I could have met Tytla and told him how much I admired him. Milt had that opportunity and took advantage of it, and he even persuaded Tytla to accept a ride home from work every afternoon. They talked on those short drives, and one day, Milt has written,

he seemed to get more emotionally charged up than usual, and started to talk about what a special privilege it had been to work at Disney's. Then suddenly his voice broke and he almost sobbed and he said, "I wish ... to God ... I had never left Disney's!" And with that he just collapsed down and didn't say another word the rest of the way home.

Tytla worked at many studios after leaving Disney—Terrytoons, Famous, various TV-commercial houses. But it was at Disney that he was not just the greatest animator—you can sense his greatness even in his Terrytoons—but a great animator who was part of something even greater than himself. He knew that, and he knew how important it was.

From Dan Briney: I was catching up on your blog tonight and came upon your posting of February 23rd ("Give 'Em the Hooks!"). The subject was hubris, and it touched a particular chord—first, because hubris is in my eyes one of the worst human vices (it was beyond unnecessary for this animator to so pointedly dismiss the other author's work in the way she did), and second, because it seems to be the attitude of too many artists who have mastered the mechanics of their craft without necessarily understanding its fundamental soul. I worked as a 3D animator for a while and was depressed at how many of my colleagues seemed to be more concerned with the hot new plug-ins and nifty-looking texture maps than anything else. It sounds as if the same thinking is at work with the author in question: having simply established herself as a technician is enough to trump an author who likely understands far more about a skill—acting—necessary to great animation. (Walt Disney himself was a hell of an actor, though he may never have picked up an animation pencil after the mid 1920s.)

The Milt Gray anecdote about Bill Tytla—long one of my very favorite animators, for obvious reasons—was sobering indeed. We hear so much about the "star" animators and directors; Tytla was certainly one of the brightest stars of all. What we don't hear about are things like this. I was saddened to read about how bad things had gotten for him, and moved by Gray's account of the grief Tytla expressed—the heavy knowledge, all those years later, of what he had lost. I may not have the tenth of the talent of a Tytla but I know what that kind of regret feels like; I suppose a lot of us do. My heart goes out to him, God rest his soul.[Posted March 28, 2009]

Coraline

I saw it last weekend, in 3-D, and I enjoyed it, as I expected, although I left the theater wondering just how much stop-motion I'd seen on the screen and how much CGI. A good bit of the latter, surely (as evidenced by the end credits, as well as by some scenes that would probably be impossible in traditional stop motion). Regardless, Coraline is a visual dazzler. It's when I see Henry Selick's films, even more than those of the Aardman studio, that I can understand the appeal of stop motion to animators of a certain kind: there is surely a tactile pleasure in manipulating those figures and settings that makes animating via computer seem dry and stifling by comparison.

I saw it last weekend, in 3-D, and I enjoyed it, as I expected, although I left the theater wondering just how much stop-motion I'd seen on the screen and how much CGI. A good bit of the latter, surely (as evidenced by the end credits, as well as by some scenes that would probably be impossible in traditional stop motion). Regardless, Coraline is a visual dazzler. It's when I see Henry Selick's films, even more than those of the Aardman studio, that I can understand the appeal of stop motion to animators of a certain kind: there is surely a tactile pleasure in manipulating those figures and settings that makes animating via computer seem dry and stifling by comparison.

It's in telling his story that Selick has serious problems. Coraline is slow to start, then seems to end several times before it finally shudders to an anticlimactic halt, exactly the sort of ending that can send audiences out of the theater feeling a little let down (and can damage box office over the long haul). Mark Mayerson is harsher on the film that I'm inclined to be—"just eye candy"—but I can't quarrel with his analysis of the shortcomings of Selick's writing (which may be in part attributable to the Neil Gaiman book, which I haven't read). The best movies turn aside the unanswered questions their stories have raised, but Coraline doesn't quite manage to do that.

Let me recommend another Mayerson post, on timing in silent comedy, specifically some of Chaplin's. Much of the meat of this post will be familiar if you've read books like Walter Kerr's wonderful The Silent Clowns and seen a healthy helping of Chaplin's films, but it's still very much worth your time. I particularly like Mark's concluding paragraph, about the influence of silent comedy on the Hollywood cartoons made a decade and more after those comedies expired. As Mark expresses one lesson Tex Avery in particular absorbed, "Fast is funny, especially when it's been combined with movements that read clearly."

And that is, come to think of it, a problem with Coraline and any number of other recent animated films: gags or plot points are diminished or lost because some action doesn't read clearly enough. Maybe that's because filmmakers expect their MTV-trained audiences to pick up everything very quickly; or maybe it's because the filmmakers haven't mastered the critical distinction between the clear and the obvious. Obviousness is bad, but clarity is good. Chaplin could have told you that.

February 22, 2009:

The First Disney Annual Report

I've been in one of those states of mind when any excuse not to post seems like a good excuse, and in such circumstances there's only one thing to do: crank up the scanner.

I've been in one of those states of mind when any excuse not to post seems like a good excuse, and in such circumstances there's only one thing to do: crank up the scanner.

So, here are scans of Walt Disney Productions' first annual report to its stockholders, for the fiscal year that ended on September 28, 1940. The Disney studio had gone public about six months before, after seventeen years of ownership by Walt and Roy and their wives. As you'll see (and as you probably already know, especially if you've read The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, it was not a happy time for Walt, his company, or his stockholders.

When I was researching and writing that book, I tracked down copies of all the annual reports issued by Walt Disney Productions and its successor, the Walt Disney Company. Most of the reports from Walt's lifetime I have in photocopies; almost all the reports from after his death I have as "originals." Happily, I have an "original" of the very first report, and that copy is the source of the scans you see here.

It's remarkable, when you consider the historic value of such annual reports, how difficult they can be to find. Copies do turn up on eBay, of course, but I'm thinking about their availability in, for example, the libraries of graduate business schools. It required inquiries to dozens of libraries, and the good will of a number of librarians, for me to assemble my set of annual reports. I thought for a long time that the 1949 and 1953 reports were going to elude me, but ultimately they didn't.

To read the annual report, click on this link, which will take you to the index page, or on the report's cover, which will take you to the same place. And in case you're wondering: the back cover of the report is blank, and so I haven't scanned it.

February 13, 2009:

Some Disney Loose Ends

Marceline Faces: John Donaldson writes with this information about the Marceline, Missouri, photographer who took the pictures of the people who were probably Walt Disney's childhood neighbors in my February 11 item: "The photographs were taken by John A. Nickell, who operated such studio in Marceline, from 1888 to 1920...during which time, serving for several years, as Linn County Judge John A. Nickell...(note J.A.N. monogram on card)."

At Hyperion and Griffth Park: Gunnar Andreassen, who located the 1927 photo taken a few steps from the early Disney studio that I posted here on February 7, has also turned up the photo at the right. It was, as Gunnar says, "taken some years later from almost the same spot. They changed the façade of this building"—the organ factory that Walt and Roy Disney bought when they expanded the studio—"but it must be the same one."

The Mystery Man: Gunnar Andreassen has also come up with a plausible identity for the unidentified man in a publicity photo for the 1941 Disney feature The Reluctant Dragon that I reproduced here on October 18, 2008. "My guess is: Al Perkins.There were five screenwriters on this film: Ted Sears, Al Perkins, Larry Clemmons, Bill Cottrell and Harry Clork. At least three of them were sitting on the back row: Sears, Clemmons and Cottrell, we see only the arm of the latter in the photo, but he’s visible in the film. Harry Clork was born in 1888 and was probably to old to be The Mystery Man. He only worked for Disney on this film. Al Perkins had been employed for some time, and as you write in The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney (pages 147-48), he had written a 161-page 'analysis' of Alice in Wonderland. In one of the photos from the photo gallery on the DVD he is seen standing and talking to Ted Sears. I would think it very probable that these writers were sitting besides one another—and the most probable fourth guy is Al Perkins. (As you may know, he was also one of the writers of an unmade feature film that ended up as the Barks/Hannah comic book Donald Duck finds Pirate Gold.)"

February 12, 2009:

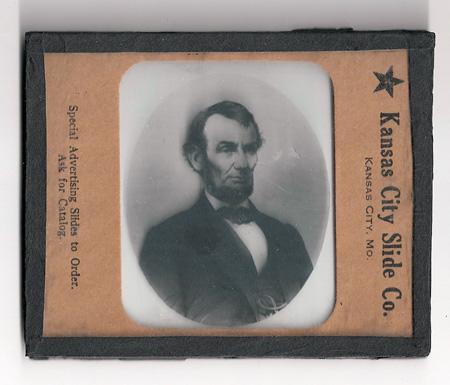

Happy Birthday, Honest Abe

Abraham Lincoln was born on this date two hundred years ago. To mark the occasion, here's a slide with the sixteenth president's portrait, which Kansas City Slide Co. used many years ago to promote its "special advertising slides." Those slides were shown in silent-movie houses early in the last century. Walt Disney went to work for Kansas City Slide in February 1920, shortly before it changed its name to Kansas City Film Ad Co.; it was there that he first began animating.

For the record, this slide is four inches wide and three and one-quarter inches deep, and is made of glass; it bears scant resemblance to modern paper-and-plastic slides. Surely there are other vintage slides from Kansas City Slide floating around (I found this one on eBay, where else),but I have yet to see any of them.

February 11, 2009:

Marceline Faces...

These "cabinet cards"—called that because the photos were attached to heavy card stock that could be stood upright in a display cabinet—were taken by a photographer named Nickell in Marceline, the small town in northern Missouri where Walt Disney spent the happiest years of his childhood. The photos aren't dated, but Marceline itself wasn't incorporated until 1888, and so the photos were likely taken in the 1890s or early 1900s, by which time cabinet cards were falling out of favor. I haven't found a trace of the Nickell firm in the book published for Marceline's seventy-fifth anniversary in 1963, but there are photos in that book, bearing dates from early in the last century, that could have been taken in the same setting as the three above.

In other words, these cabinet-card subjects are people that Elias and Flora Disney and their children could have known, or certainly brushed against as they shopped on Marceline's main street, Kansas Avenue. And how strange they look—not just stiff and uncomfortable, but remote, as if they were separated from us by centuries, and not just a hundred years or so. I'm reminded when I look at these photos of just how radically different America was, when Walt Disney was a boy, from the country that he would know in middle age. As much as the America of 2009 differs from the America of 1959, those differences are as nothing compared with the gulf between the America of 1959 and the America of 1909.

We have computers and cell phones, but like our parents, we live in a world of automobiles and television and airplanes. Walt Disney's parents had a telephone, but he remembered when the first cars appeared in Marceline, around 1908, and it was a long time before most of the twentieth century's other advances penetrated that little town. Fifty years ago, Walt and his contemporaries were living bridges between two radically different Americas, as even people born a few years later were not. When Walt was a boy it was mostly the railroad that kept Marceline in touch with the wider world; small wonder, as I've written in The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, that he loved trains so much.

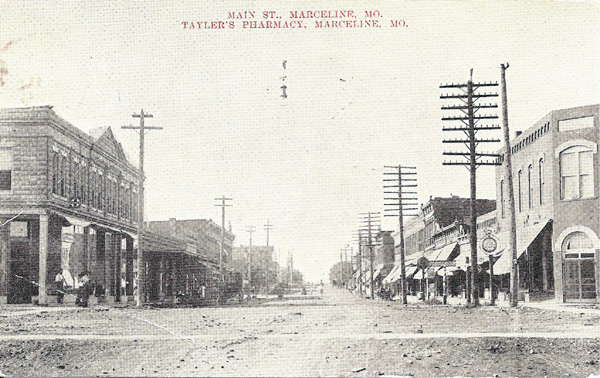

...And a Marceline Myth

Last October, when Walt Disney Imagineering announced plans for a makeover of the troubled Disney's California Adventure theme park in Anaheim, the Los Angeles Times said that the revamped park would "transport visitors to the California of the 1920s, when Walt Disney first arrived in Hollywood, in the same way that Disneyland's Main Street evokes Disney's hometown of Marceline, Mo."

That notion—of a tight connection between Marceline's Kansas Avenue and Disneyland's Main Street U.S.A.—has long been conventional wisdom. Even Walt's detractors take the connection for granted, as in this passage from Peter Stephan Jungk's infantile novel about Walt, The Perfect American, when his protagonist, a disaffected Disney artist, has come to Marceline:

Marceline's fire station, barber's shop, town hall, candy shop, and clothes store, even the little movie house: they all strikingly resembled the buildings along Main Street U.S.A., the principal artery in Disneyland.

Certainly the town of Marceline, which has renamed Kansas Avenue "Main Street U.S.A.," has every reason to want you to believe that when you go there you'll see Disneyland's "principal artery" in embryo. But it's not true, and it really couldn't be.

One problem is that even if Walt wanted to recreate the early 1900s Kansas Avenue in Disneyland, he had very little in the way of specific memories to work with. He visited Marceline only one time between 1911, when his family moved to Kansas City, and 1955, when Disneyland opened to the public. I wrote last year about that very brief visit, which took place in 1946, long before Disneyland was more than a gleam in Walt's eye.

Disneyland—and Main Street U.S.A.—had been open for a year when Walt, accompanied by his brother Roy and their wives, made his first overnight visit to Marceline, on July 3-4, 1956, for the dedication of the Walt Disney Municipal Park. Speaking to the columnist Hedda Hopper just before he left for Marceline (her column appeared in the Los Angeles Times on July 5, 1956), Walt said: "I don't remember much about the town. I was 9 when I left, but I drove through it about 10 years ago."

Early authorized books about the park, like the guidebooks and Marty Sklar's Disneyland, which was first published in 1964—during Walt's lifetime—make no mention of Marceline. Sklar sums up Main Street U.S.A. as "'anywhere in America,' circa 1900" and quotes Walt as saying: "Many of us fondly remember our small home town and its friendly way of life at the turn of the century. ... Main Street represents the typical small town of the early 1900's—the heartline of America." A lot of small towns looked at least as much like Disneyland's Main Street as Marceline did; that was the whole idea.

In fact, we know exactly what Kansas Avenue in Marceline looked like when Walt lived there, thanks to photos on postcards. As strange as it now seems, in those days buildings and streets and parks throughout Marceline were pictured on postcards, no doubt because postcards were used so heavily—they cost just one cent to mail, and so were a cheap and easy way to communicate. Here is a postcard depicting Kansas Avenue, circa 1909 (the date of the postmark); any resemblance to Disneyland's Main Street is, at best, extremely general.

Walt unquestionably had fond memories of his years in Marceline, but his specific memories were all of life on the family farm. There's no reason to believe that he tried to translate a general affection for the town into something as concrete as Main Street U.S.A.

Any of Walt's memories that played an important part in the conception of Main Street U.S.A. were probably not memories of Marceline, but rather memories accumulated during three decades in Hollywood. The "small towns" that most resemble Main Street U.S.A. are made up of stage sets—they're the "towns" that serve as backdrops in movies like Meet Me in St. Louis and It's a Wonderful Life, and in Walt's own So Dear to My Heart.

As Robert Neuman of Florida State University says in an excellent article, "Disneyland's Main Street, USA, and Its Sources in Hollywood, USA," published last year in The Journal of American Culture, "it was the medium of film that in the 1930s and 1940s indelibly established the idea of the quintessential small town, with its train station, main street, and residences, thus reinforcing, invigorating, and giving meaning to the hometown experiences of millions of Americans. Walt Disney's method and purpose in visualizing the little town at the entrance to Disneyland through the collaborative efforts of his creative team was not only analogous to but influenced by these movies."

And while I think of it, this link will take you to a page of photos I took during a visit to Marceline four years ago.

February 7, 2009:

Hyperion Avenue at Griffith Park Boulevard, 1927

Gunnar Andreassen found this photo in the University of Southern California's digital archive showing the intersection of Hyperion Avenue (left to right) and Griffith Park Boulevard in Los Angeles in 1927. The building at the right is apparently the organ factory that the Disney studio bought for additional office space in the early 1930s; if the photographer had swung his camera a little more to the right, he would have given us a glimpse of the early Disney studio itself. Walt and Roy Disney and their staff had moved into that new building at 2719 Hyperion in 1926.

The photo itself has no Disney connection, of course; its real subject is the new "caution flasher" at the center of the picture. You can learn more at this link.

Gunnar has pointed me toward other online photos taken in the 1920s in the same general vicinity. In this case, as in others, I couldn't suppress mild surprise at how unfinished that part of L.A. looked then, how raw and even semi-rural. I've always known, as a piece of abstract knowledge, that Hollywood and other nearby areas were developed not long before Walt arrived in town, but it's good to be jolted into a fresh awareness of just how new everything really was.

CGI Politics

I think almost everyone who visits this site knows better than to take seriously the animation organization called ASIFA-Hollywood, but if you follow animation at all you could hardly escape hearing about ASIFA's annual Annie Awards ceremony last week. The big news was Kung Fu Panda's eyebrow-raising sweep over Pixar's favored (and much over-praised) WALL-E. Studio politics evidently figured heavily in the results, but I'm sure many ASIFA members actually do prefer the relatively unpretentious Kung Fu Panda.

A lot of other people find all computer animation increasingly troubling, for reasons one of my visitors, Geoffrey Hayes, states clearly of in a message I've posted on the Feedback page devoted to such films; you can read what he says by clicking on this link. I understand the worry Geoffrey expresses about two forthcoming Disney features, the hand-drawn Princess and the Frog and the CGI Rapunzel: "My fear is that they will 'work' as films; that is, hit all the right buttons, have a tight, well-paced plot and technically good animation, yet lack that one ingredient that all the classic Disney films have: true magic." An entirely reasonable fear, I think, especially given the state of the economy and the likelihood that businesses of all kinds, movie studios included, will find it increasingly tempting to play things very safe.

Reading Over My Shoulder

As Mark Mayerson, Gunnar Andreassen, and Geoff Blum have all mentioned to me, my correspondence with Carl Barks—Carl's side of it, that is, my letters to him and his drafts and copies of his replies—is now up for auction on eBay, as part of the ongoing auction of items from the Barks estate; the lot is described at this link. Starting bid is two hundred dollars. I don't expect to make an offer. I treasure my letters from Carl, but what I have in my files seems like enough.