March 31, 2008:

March 28, 2008:

March 26, 2008:

March 24, 2008:

March 22, 2008:

March 21, 2008:

March 20, 2008:

A Day in the Life: Disney, January 1930

The Animated Man in Trade Paper

March 18, 2008:

March 15, 2008:

March 14, 2008:

March 13, 2008:

A Day in the Life: Walt Kelly, 1955

March 12, 2008:

Who's The Man With the Cigarette?

March 11, 2008:

"In the End, He Decided to Go Negative"

March 7, 2008:

Accentuating the Negative, Cont'd

March 6, 2008:

A Day in the Life: Disney, February 1927

March 5, 2008:

March 3, 2008:

March 2, 2008:

March 31, 2008:

Assorted Briefs

Thanks to Hans Perk, the number of unidentified people in the 1930 Disney studio photographs has dwindled further, but the names of some of the studio's female employees remain mysteries. I've also identified the man at the left in the photo I posted on March 26.

Speaking of Hans Perk: He has been posting the draft, or scene-by-scene record, of One Hundred and One Dalmatians, and Mark Mayerson is now translating the draft into one of his extraordinary mosaics. Wonderful stuff. And Floyd Norman ("Mr. Fun"), a living repository of Disney history, has finally started his own blog. A round of applause for all three gentlemen.

I've finally finished reading David Michaelis's biography of Charles M. Schulz, Schulz and Peanuts, and I'll gather my thoughts about that book while I'm away the rest of this week on a short trip. I also have the DVD of Nick Cross' The Waif of Persephone, and I'll share my second thoughts about that film after my return.

March 28, 2008:

The Man in the Glass

After reading my March 26 item, about the first meeting of Walt Disney and Rudy Ising in, probably, February 1922, David Lesjak, proprietor of Disney - Toons at War, wrote to ask about the man whose reflection is visible in the window glass behind Ising (see the enlargement above). Who is it, and what is he doing? Interesting questions, for which I have no ready answers. Is this a glimpse of Walt directing live-action filming, during which this still photo was taken?

March 26, 2008:

When Rudy Met Walt

[A March 31 update: As I've confirmed from another photo, with identifications by Max Maxwell, the man at the left above is Adolph Kloepper.]

If you've read pages 29-31 of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, you know that there was a period in Walt's life, beginning in the fall of 1921 and ending with the incorporation of Laugh-O-gram in May 1922, that has resisted efforts to pin down what was going on. Walt himself was remarkably consistent and accurate in what he said about his personal history, but even his accounts of these six or seven months were a little murky.

Rudolph Ising's interviews, with me and with J. B. Kaufman, have been helpful, but Rudy—who turned eighteen in 1921, fifty years before I first interviewed him, in 1971—quite understandably couldn't remember the exact date when Walt hired him to work at what was then called Kaycee Studios. (That's Rudy at the right in the posed photo above; I probably should know who the other man is, but at least it's not Walt.) Various scraps of evidence have suggested strongly that Rudy was hired in early 1922, but there was nothing definitive. I've always known the date would be good to know, because with that date as an anchor, other events might start falling into place. I rounded up a lot of contemporary documents—city directory pages and the like—when I was writing the book, but they were of limited help.

Recently I've been corresponding with Tim Susanin, who shares my intense interest in this formative period of Walt's career, and we decided there was nothing to be done but plunge into the vast morass of newspaper microfilm from the period. Happily, when I reviewed the "educational" want ads in the Kansas City Star for Sunday, February 5, 1922, I found this ad, which apparently ran on no other date:

This was in all likelihood the ad that Rudy Ising read and answered by "calling" in person that Sunday afternoon at Kaycee Studios, where he was interviewed by the twenty-year-old Walt Disney. Kaycee Studios evidently had no telephone; and Walt had to do his interviewing on Sunday afternoon because he was working six days a week for A. V. Cauger at Kansas City Film Ad. This ad also provides the actual street address for Kaycee Studios; Kaycee was above Peiser's restaurant at 3239 Troost, but the door to the stairs leading up to the second floor must have been numbered 3241. (That address has been identified incorrectly, as in the book Walt Disney's Missouri, as that of one of the boarding houses where Walt lived.)

So, there's more to work with now, and I'll be pulling my Kansas City files and seeing which old scraps take on new meaning now that I have this additional information. But not so fast: Was Rudy Ising the only person who answered that ad? Walt spoke in interviews of making his first Laugh-O-gram fairy tale, Little Red Riding Hood, with a crew of students in the family garage, as in this 1935 account by a newspaper reporter:

The garage studio was enlarged and Disney obtained the aid of several young artists who, in return for his instruction in cartooning, helped him with the drawings for "Red Riding Hood." It took six months to make this film, working nights and other spare time.

"When I finished it," Disney says, "I quit my job and formed a company, capitalized for $15,000, to make a series of these modernized fairy tales."

That $15,000 figure is correct, by the way; such accuracy was typical of Walt. But did those "young artists" answer the February 5 ad? Or was there an earlier ad, perhaps one that ran in the fall of 1921 before Walt's parents moved to Oregon and presumably rendered the family garage unavailable? Rudy Ising was almost certainly not one of the "young artists" who worked on Red Riding Hood; he remembered working with no one at Kaycee Studios except Walt and the cameraman Red Lyon. Did Walt have a garage studio going at the same time as Kaycee Studios, keeping the existence of each a secret from the other, perhaps so the "students" wouldn't get irked at not being paid? Why was Four Musicians of Bremen, and not Red Riding Hood, the cartoon listed among Laugh-O-gram's assets when it was incorporated?

No answers yet, but stay tuned. We have a lot more microfilm to look at.

March 24, 2008:

Looking on the Bright Side

[A March 25 update: To read more about the supposed Hitler drawings of Disney characters, click here; thanks to Are Myklebust for the link. And while I think of it, I feel compelled to deny the persistent rumors that well-known animation scholars are at work on volumes variously titled The Art of Adolf Hitler, The Hitler That Never Was, and Adolf Hitler's Nine Old Men and the Art of Annihilation.]

John K. Richardson wrote in response to my recent essay called "Accentuating the Negative":

Here’s a quick practical tip that I just wanted to send off. If you wish to seem more positive in your outlook or appraisal of a beloved historical figure, try just swapping the halves of the last sentence you write about that person. Observe:

"Although he crafted some of the most poignant and hilarious cartoons in the world, thereby leaving a legacy of love that transforms countless communities even today, 'Chortles' Minky nevertheless methodically murdered most of his closest friends and their helpless children with gleeful pride."

NOW, WE MAKE THE SWAP:

"Although he methodically murdered most of his closest friends and their helpless children with gleeful pride, 'Chortles' Minky nevertheless crafted some of the most poignant and hilarious cartoons in the world, thereby leaving a legacy of love that transforms countless communities even today."

Even in this extreme example (which has been fabricated for laboratory purposes), you can see the power of simply reversing the clauses. Try it now on some actual historical figures. Simply find your "summation sentence" (which often lies at the end of a paragraph or chapter) and use a piece of scrap paper to experiment. You need not omit any salient negative facts, either, so your journalistic integrity remains unharmed. Just a quick tip from a natural optimist!

OK, I'll try it. Here goes:

Adolf Hitler, best known as a bloodthirsty tyrant who inflicted death and misery on tens of millions of innocent people, may also, we have learned recently, been a pretty good cartoonist who liked to draw Walt Disney characters.

Son of a gun! It works, doesn't it?

March 22, 2008:

This from Germund von Wowern:

Richard Huemer and Germund von Wowern are about to finish work on a book collecting Dick Huemer's and Paul Murry's hard-to-find comic strip Buck O'Rue. Practically the entire run January 15, 1951, to late 1952 is already scanned from black/white proofs and prepared for publishing. The year 1951 is already complete, but some artwork from 1952 is still missing and they would appreciate very much to get in touch with anybody able to supply the final strips. They are only missing one single Sunday entirely (January 20, 1952), but would like to obtain the full 12-panel versions of the following: February 3, May 4, June 8, 15, 22, 29, July 6, August 10, 17, 24, December 14 and later (if they were even produced). The dailies are complete, January 15, 1951, to July 19, 1952, except the week of July 7-12, 1952. These late dailies were probably never even published in newspapers at the time, but were most likely drawn. We've been searching for these last Sundays for quite some time now, so managing to locate just a few of them would be a great step forward.

Dick Huemer was, of course, the Disney animator and story man whose credits include, among many other things, the animation of Donald Duck in The Band Concert and (with Joe Grant) the writing of Fantasia and Dumbo. Paul Murry's name is closely associated with the many Mickey Mouse comic-book stories he drew in the 1950s and '60s.

If you have any of the missing strips, let me know, and I'll forward that information to Germund.

Missing Links

As you may have noticed, I've been expanding my list of links to other sites, including a few that I find suspect but where worthwhile material does occasionally turn up. As the old saying goes, even a blind hog sometimes finds a truffle, and I'm sure my visitors are savvy enough to distinguish the truffles from superficially similar objects.

March 21, 2008:

More Disney in January 1930

[A March 22 update: Thanks to Hans Perk for identifying Bill Cottrell and Hazel Sewell in two of the photos, and for pointing out that I'd identified Chuck Couch in one but not in another.]

I realized after posting yesterday's "Day in the Life" page, devoted to the Disney studio in January 1930, that I'd accidentally left out one photo—a particularly poignant one, since it shows Walt kneeling between the two valued colleagues, Ub Iwerks and Carl Stalling, who would leave him just a few days later. It's now the fourth photo from the top; you can go to that Essay page by clicking on this link, and you can go directly to the added photo by clicking on this one.

Thanks to Hans Perk, for suggesting that I post larger versions of the two photos with unidentified staff members; you can access those larger versions by clicking on the two photos on the January 1930 page. Hans also provided a descreened scan of a photo missing from my files, so that there are now ten photos altogether from that day almost eighty years ago. And thanks to Michael Sporn for spotting an identification (of Wilfred Jackson) I'd accidentally omitted.

As I clean up my photo files, I'm finding more and more groups of photos that lend themselves to "Day in the Life" presentation, so you can count on this series continuing for quite a while.

March 20, 2008:

A Day in the Life: Disney, January 1930

My third such Essay showcases eight photos taken at Walt Disney's Hyperion Avenue studio on one day in January 1930 (or possibly late December 1929). This is the Disney studio as it existed just before Ub Iwerks and Carl Stalling left. To visit that page, click on this link.

The Animated Man in Trade Paper

The trade paperback of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney that I'd ordered from amazon.com arrived earlier this week. I'm very happy with it, not only because I got to eliminate some annoying little errors that crept into the hardcover, but also because the book somehow feels "right" in trade paper.

The trade paperback of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney that I'd ordered from amazon.com arrived earlier this week. I'm very happy with it, not only because I got to eliminate some annoying little errors that crept into the hardcover, but also because the book somehow feels "right" in trade paper.

The hardcover's jacket design, which always seemed to me a little stark, looks sharp and crisp on the paperback. There's a bit of softness in the way a hardcover is bound and its jacket is folded, whereas a paperback's edges are more clearly defined; Animated Man's cover design seems tailored to that paperback characteristic.

I like the way the book feels in the hand, too. In hardcover, big, bloated books can feel more "serious" than a modestly scaled volume like The Animated Man, but in trade paper an 800-page book can seem clunky and hard to handle. The trade paper version of The Animated Man feels to me like a book that's just the right size for, say, a cross-country flight. I hope a fair number of people think of it in those terms.

March 18, 2008:

Yma, Definitely

Not that there was much doubt, but that's definitely Yma Súmac with Walt in the March 15 photo. David Lesjak pointed me to this page on one of two "official" Yma Súmac Web sites; I'd visited it before, but I'd missed the photo of Yma with Walt that was clearly taken during the same visit as the photo I posted, and that I've borrowed for posting here. According to the Súmac site, she and Walt met during his 1941 visit to South America.

Not that there was much doubt, but that's definitely Yma Súmac with Walt in the March 15 photo. David Lesjak pointed me to this page on one of two "official" Yma Súmac Web sites; I'd visited it before, but I'd missed the photo of Yma with Walt that was clearly taken during the same visit as the photo I posted, and that I've borrowed for posting here. According to the Súmac site, she and Walt met during his 1941 visit to South America.

As for the occasion of her visit to the Disney studio, John Donaldson writes: "In May of 1947, Yma Súmac (then, as Imma Sumak), was appearing in the stage show 'Ballet Español' at the Wilshire Ebell Theatre, along with husband, Moises Vivanco...Carlos Montoya on guitar, Pablo Miquel, piano...and several fancy dancers."

Still no identification for the man with Yma and Walt, but possibly he's one of the "Ballet Español" musicians (not Carlos Montoya, though).

March 15, 2008:

Who's That With Walt?

This is an "official" Disney photo, but, according to Dave Smith of the Walt Disney Archives, the only definite information about it comes from the negative number, which shows that it was taken in May 1947. Dave writes: "Someone has identified the woman in that photograph as Yma Súmac. We do not know who the man is. Perhaps her husband? ... I didn’t find their names in Walt’s desk diaries for that month."

Súmac, a Peruvian coloratura soprano with a phenomenal range, was popular in the 1940s and '50s; now in her eighties, she lives in the Los Angeles area. She was married to a composer and bandleader named Moises Vivanco in 1947, but the man in the photo does not appear to be Vivanco.

The Man With the Cigarette

Another mystery, broached in a March 12 item—the identity of a mustachioed, cigarette-smoking man in a photo with Walt Disney and Igor Stravinsky—has been solved. This from Alexander Rannie:

Robert Tieman at the Disney Archives was able to identify the man with a cigarette in the Stravinsky/Balanchine/Disney photo as Gregory Golubeff, "Stravinsky's manager" (according to a handwritten note on the back of a print of the photo at the Studio). Stephen Walsh's bio of Stravinsky (Stravinsky: The Second Exile: France and America, 1934-1971 (New York: Knopf, 2006) says (p.116) that Grigory [sic] Golubeff was an assistant to Alexis Kall, Stravinsky's friend and sometime agent, and offers the following footnote: "Golubeff (1891-1958) was an American-born, Russian-educated musician, writer, and translator (of, for example, Pushkin) who had shared Kall's house in Los Angeles for a time and had undertaken agency work for Stravinsky on the West Coast (see Kall and Stravinsky's joint letter of authorization to him of 21 December 1939 in PSS [Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel]). He translated Renard and an essay, 'Pushkin, Poetry and Music,' supposedly by Stravinsky but in all probability ghosted by Golubeff himself."

I also found out that Golubeff did a little acting, appearing in such films as Rhapsody in Blue, The Mask of Dimitrios, and Casablanca, no less! (Seems everyone got into the act, as Dr. Alexis Kall appeared in the 1944 film Song of Russia.) So the reason Golubeff may look familiar is that we've all seen him (albeit briefly) in Casablanca.Now we can definitively identify everyone (from left to right): Dr. Alexis Kall (friend of and sometime agent for Stravinsky, and former pupil, alongside Stravinsky, at the St. Petersburg Conservatoire), composer Igor Stravinsky, Gregory Golubeff (Stravinsky's manager/assistant to Kall), choreographer George Balanchine, Walt Disney, and "Dance of the Hours" director T. Hee.

And per your reader's comment, the photo was taken in 1939 (probably in late December, just before Christmas), as that was when Stravinsky and Balanchine toured the Disney Studio. (If you look at the storyboards in the photo, you can see they're from "Dance of the Hours" which, along with the presence of T. Hee and the smiles on everyone's faces, suggests they are looking at footage from "Dance of the Hours.")

Although initially contacted by Disney in 1938 about the possible use of his Firebird ballet, Stravinsky ultimately signed a contract for the Rite of Spring in January of 1939. On October 28, 1940 (before the November 13 premiere of Fantasia), he signed a contract for the exploitation of The Firebird, Renard, and Fireworks. It should be noted that all of these Stravinsky works were in public domain in the United States, and Disney needed Stravinsky's permission only for distribution outside of the U.S.

Stravinsky did not, on that 1939 tour, see any footage from the Rite of Spring (contrary to his comments in Expositions and Developments (London: Faber and Faber, 1962), pp. 145-146), although he did listen to the recording by Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra. It was only later, on October 12, 1940, that he finally saw the completed film. Stephen Walsh notes in Volume 2 of his Stravinsky biography (p. 600n56): "He [Stravinsky] was in fact by no means unequivocally hostile [to the use of his music in Fantasia.] When Fantasia came up in conversation with [composer Paul] Hindemith in New York the following January [1941], Hindemith found the whole idea "truly unedifying," but added that "Igor appears to love it" (letter of 30 May 1941 to Willy Strecker, in Skelton, ed., Selected Letters of Paul Hindemith, p. 177).

And speaking of Paul Hindemith, you can read about his encounters with Walt Disney by clicking on this link and reading the Essay by Donald Draganski.

March 14, 2008:

Paperback Writer

Amazon.com notified me today that it has shipped the trade paperback of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. The book still shows on amazon's page as a pre-order, but University of California Press confirms that the book is now available. As I've noted before, the paperback corrects almost all of the errors that turned up after publication of the hardcover a year ago; those errors—most of them decidedly minor, I'm happy to say—are cataloged here.

To mark the occasion, here's another photo of Walt taken in England in the summer of 1951 during the filming of The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men; this one was taken the same day as the photo I published here February 6. As in the earlier photo, Walt is in the company of Richard Todd, who played Robin Hood, and Joan Rice, who was Maid Marian. Todd and Ken Annakin, Robin Hood's director, both told me when I interviewed them for The Animated Man that Walt's visits to the set were infrequent and low-key, but, fortunately for us, an exception was made on this day for the sake of the publicity shots.

Following Up

The Man With the Cigarette: No one has stepped forward yet with an identification of the man in a March 12 item, but B. Baker raises this question:

As that's a picture from 1939 or 1940, the Moviola appears to be running reels of 35mm nitrate film. After reading numerous accounts over the years of disastrous projection room fires... why would anyone be smoking around that thing?

Robert Parrish's memoir Growing Up In Hollywood features a nice anecdote on how one of his duties as a young associate editor involved keeping his boss' cigarette lit. This wasn't an easy matter, as the cigarette was actually at the end of a very long tube extending outside the cutting room.

Baker also asks if the mystery man could possibly be Virgil Partch. Seems unlikely to me, but I don't have a photo of Partch handy.

Walt Kelly: David Lesjak has turned up pages in several small-city newspapers that used some of the photos in that Kelly publicity package that was the subject of my March 13 photo essay. Some papers also used Kelly's tongue-in-cheek biography as filler, running it as a straight news item. One wonders what the readers of the Abilene Reporter-News thought of it; or how about the readers of Stars and Stripes?

As a reminder, David Lesjak is the proprietor of two excellent Disney fan sites, Disney - Toons at War and Vintage Disney Collectibles, both of which should be among your RSS feeds if you pretend to a serious interest in Disney matters.

"Accentuating the Negative" Feedback: Gordon Kent has added some illuminating comments about Frank Rich's theater reviews for the New York Times, which have turned out to have some surprising relevance to this discussion. You can go directly to Gordon's comments by clicking here.

March 13, 2008:

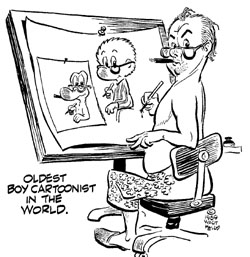

A Day in the Life: Walt Kelly, 1955

In that year, the Hall Syndicate, which distributed Walt Kelly's great comic strip Pogo, sent its client newspapers eight photos of Kelly, all probably taken on the same day. I don't know which day, but there are no doubt clues in some of the photos.

In that year, the Hall Syndicate, which distributed Walt Kelly's great comic strip Pogo, sent its client newspapers eight photos of Kelly, all probably taken on the same day. I don't know which day, but there are no doubt clues in some of the photos.

The idea was that the newspapers would run the photos, which were accompanied by Kelly-authored gag captions, as a sort of feature spread. I don't know how many papers bit; not many, I suspect. But you can see all eight photos, in the second of my Day in the Life series of groups of photos taken on the same day, by clicking on this link.

Next up: a group of photos taken on the same day, probably in early January 1930, at the Disney studio.

March 12, 2008:

The Busy Little Spammers

They've appropriated my domain name again recently, and as a result, I've just learned, Comcast has been blocking mail forwarded to me from this site. It's time to withdraw to a more secure position, and so I'm scrapping my michaelbarrier.com email address and listing just my standard email address, michaelbarrier [at] comcast.net, for feedback. I hope that listing it in that form will discourage "harvesting" by lowlifes, although their ingenuity seems to know few limits.

Fortunately, B. Baker managed to elude the anti-spammers and offer some cogent comments on my piece called "Accentuating the Negative." To go directly to Baker's comments on the relevant Feedback page, click here.

Who's the Man With the Cigarette?

From Alexander Rannie, this photo taken during Igor Stravinsky's visit to the Disney studio during the production of Fantasia, and a question: Who's the man with the cigarette? He looks naggingly familiar, but I can't come up with a name. Here's what Alex says:

The folks in the photo are (from left to right): Alexis Kall (friend of and sometime agent for Stravinsky, and former pupil, alongside Stravinsky, at the St. Petersburg Conservatoire), composer Igor Stravinsky, unidentified (for the moment), choreographer George Balanchine, Walt Disney, and "Dance of the Hours" director T. Hee. FYI: The photo is published in Stravinsky: The Second Exile: France and America, 1934-1971 (New York: Knopf, 2006), the second volume of Stephen Walsh's definitive biography of the composer. The source for the photo is credited as the Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel.

And Speaking of Walt...

As I mention on page 134 of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, Walt was heavily involved in sports of various kinds by the late 1930s, especially skiing. Jeff Pepper has posted an admirably detailed page about Walt and his involvement in the Sugar Bowl ski resort on his excellent 2719 Hyperion site. I realized, in reading Jeff's post, that I was off by one year when I mentioned Walt's role in financing the resort; he began putting money into it in 1939, not 1938. I can't make that fix in the first printing of the paperback, unfortunately, but I've noted my error on the page devoted to Animated Man corrections.

March 11, 2008:

"In the End, He Decided to Go Negative."

Cartoon and caption/heading are from the current New Yorker, and the reference is to my piece called "Accentuating the Negative." I haven't heard from anyone other than Nick Cross since I published that piece last week, but Michael Sporn posted some comments on it a couple of days ago.

I particularly enjoyed Michael's account of a private screening of Fantasia for the wonderful Hungarian-born animator Tissa David. I was reminded of the time, many years ago, when I screened Bob Clampett's Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs for the late Martin Williams, the great jazz critic and my co-editor of A Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics. Big mistake! Many people can't see past the stereotypes that Clampett manipulated so gleefully, and, unfortunately, Martin was one of the many.

Michael's comments have prompted some thoughtful responses from Pete Emslie, Thad Komorowski, Kevin Langley, Daniel Thomas MacInnes, and Tim Rauch. There's also one of those fascinating reports from Eddie Fitzgerald's delirious alternative reality, the one in which John Kricfalusi makes rib-tickling cartoons, Clampett's cartoons are "sunny," and jazz critics (not audiences and musicians) killed swing so that bebop could slither through the eardrums of the unwary young. That Eddie, he's a caution! Sometimes deliberately, as on his nifty site, but sometimes maybe not so deliberately.

I was flattered by Michael's comments about my work, but I was particularly impressed by what some of his commenters had to say about how the internet had encouraged its participants to be crude and abrupt. As Pete Emslie put it, "the internet does not seem to be that conducive to well-reasoned criticism. ... I think Mike Barrier was on safer ground in the pre-internet era, when responses were not as swift and savage as they are today. To be a tough, serious critic today requires either a very thick skin or a masochistic bent!" Or maybe both.

My heretical views on The Polar Express were invoked at a couple of places in this discussion, and I could tell that some of my colleagues were deeply fearful that my soul was in jeopardy ("Pray for Brother Barrier, that he may escape the grasp of the demon Zemeckis, child of Beelzebub"). Alas, if my Brothers in Walt would only read my review again—and my reviews of Monster House and Beowulf—they might conclude that I share most of their theological objections to mo-cap, but that I think it served a valid purpose, for perhaps the one and only time, in Polar Express. And even at that, I wouldn't presume to criticize the views of anyone who has seen Polar Express only on video. If ever a movie needed to be seen on the big screen, and preferably in Imax 3-D, it's that one.

And Speaking of Sporn...

(Try saying that out loud) Michael has been posting a lot of great stuff lately, including preliminary artwork for the Disney cartoons The Little House and Susie the Little Blue Coupe. But I think my favorite posts have been his memories of working for John and Faith Hubley. In a better world, one where artists' standing was more fairly judged, Michael would have been paid thousands of dollars to write a memoir of the Hubleys for a magazine like Vanity Fair; for that matter, Michael himself would be living a luxurious life. Given animation's low social standing, that's not likely to happen, but at least we have his amazing blog to enjoy.

March 7, 2008:

Accentuating the Negative, Cont'd

I've heard from Nick Cross, the Canadian filmmaker whose cartoon The Waif of Persephone I've twice criticized severely and, I'm afraid, unfairly, most recently in "Accentuating the Negative." Nick's message was exactly the sort of thoughtful response to that piece I hoped for but doubted I would get, which made it doubly welcome. You can read what he said, and my reply, on a new Feedback page.

As I mention on that page, I've ordered the DVD of Nick's Waif, and I'll be looking at it again soon. Whatever I think of it, I'll let you (and Nick) know, and without the unfortunate hyperbole I employed after I saw it in Ottawa.

And Speaking of Feedback...

Vincent Alexander, who identifies himself as a fifteen-year-old cartoonist, has sent me a detailed critique of my 2004 review of The Spongebob Squarepants Movie, a critique that is about as long as the review itself. I've opened up a Spongebob Feedback page to accommodate Vincent's comments. Spongebob hasn't been the subject of much comment here, but if you've been holding back because you weren't sure your thoughts on that popular show and movie would be welcome, now you know better.

March 6, 2008:

Where's Walt, No. 6

Actually, we have an idea where Walt was when this autographed photo was taken. He was quite likely in Atlanta, in November 1946, for the premiere of Song of the South. Jim Korkis, who shared this scan with me, says the photo came from the Wren's Nest, Joel Chandler Harris's Atlanta home, now a museum. "The Wren's Nest find was fairly recent," Jim says. "It was found in the attic, misfiled among some other items. You can see how faded the Walt signature is."

But where exactly was the photo taken, and who are the people with Walt? Jim writes: "It looks like actor Bill Williams (and his wife Barbara Hale who we all remember from the Perry Mason TV show), who were at the premiere, and that could be a really young Luana Patten and Bobby Driscoll. Who are the other two people in the picture? I suspect the other woman in the photo is an actress and the man who is kneeling might be the owner of the Fox Theater or some special official from Atlanta. Looks like Walt is introducing his two young cast members." Anybody know for sure?

And speaking of Song of the South and its premiere, there's an excellent article about that occasion, by "Wade Sampson" (those of you who have read The Rat Factory will recognize the name), at this link.

A Day in the Life: Disney, February 1927

I've accumulated thousands of photos over the years, for use in Funnyworld, my books, and now this Web site, and lately I've devoted some time to organizing and storing them more systematically. I've realized, as I've gone through the photos, that in some cases several photos have obviously been taken on the same day, sometimes only minutes apart. For me there's something especially poignant about such photos; there's a stronger sense of time's passing than with even the most evocative single photo.

I'm going to post such groups of photos here periodically, under the Essays tab, with the general heading "A Day in the Life." I'm starting with three photos taken at the Disney studio in 1927. More Disney will follow—those are the files I started with—but I'm sure there'll be similar pages for the Warner and MGM studios, too.

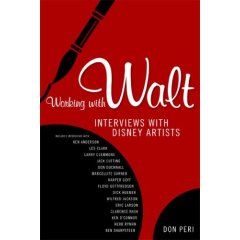

Working With Walt

That's the title of Don Peri's newly published collection of interviews with sixteen Disney artists. I read it in proofs and provided one of the three back-cover blurbs for the book, in the excellent company of Diane Disney Miller and Didier Ghez. Here's what I said (and, like Horton, I said what I meant): "I knew many of the people represented in this book, and their memories of working for Walt Disney—a demanding, stimulating, and altogether extraordinary boss—were vivid, clear, and reliable. It's wonderful to hear their voices again, and to relive their fascinating experiences, through Don Peri's interviews in this marvelous compilation."

That's the title of Don Peri's newly published collection of interviews with sixteen Disney artists. I read it in proofs and provided one of the three back-cover blurbs for the book, in the excellent company of Diane Disney Miller and Didier Ghez. Here's what I said (and, like Horton, I said what I meant): "I knew many of the people represented in this book, and their memories of working for Walt Disney—a demanding, stimulating, and altogether extraordinary boss—were vivid, clear, and reliable. It's wonderful to hear their voices again, and to relive their fascinating experiences, through Don Peri's interviews in this marvelous compilation."

Working With Walt (University Press of Mississippi, 246 pages) bears a family resemblance to Didier Ghez's excellent interview series, Walt's People, and it's equally worthy of a place on your bookshelf. The interviews are all very good, but I particularly enjoyed those with five people—Larry Clemmons, Don Duckwall, Harper Goff, Ken O'Connor, Floyd Gottfredson—whom Milt Gray and I didn't interview for Hollywood Cartoons, for one reason or another, and who didn't sit for a great many interviews otherwise. You can order Working With Walt from amazon.com (the current price is $14.96) by clicking on this link.

March 5, 2008:

Accentuating the Negative

An accusation I hear repeatedly is that I'm too "negative," that my writing isn't warm and fan-friendly. I take such complaints seriously, and you can read the results of my self-examination by clicking on this link. A warning to the sensitive: a quotation from one of my critics includes some rather coarse language.

March 3, 2008:

Bob Clampett at Work

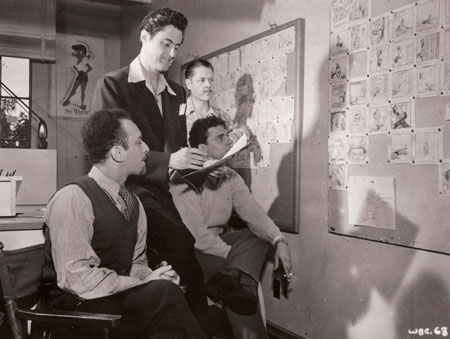

This photo of Bob Clampett was taken early in 1945, like the photo of the Clampett animators Rod Scribner and Manny Gould that I posted a few months ago (the Clampett photo was published with many others on the cover of the April 1945 issue of the Warner Club News, the Warner studio's in-house newspaper). Seated with Clampett, from the left, are story men Michael Sasanoff and Hubie Karp; layout artist Tom McKimson is standing at the rear. The storyboards are for The Big Snooze (at the left) and The Great Piggy Bank Robbery, both released in 1946. Clampett left the studio in May 1945, soon after this photo was published.

I also published this photo in Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, but I used a different print, one made from the original negative. The negative had been damaged by the time that print was made, unfortunately. The print reproduced here was copied from a print in an archival collection, and that print too had suffered some damage, noticeable in the specks on Clampett's face. Overall, though, this one probably looks a little better. As with the Scribner photo, I've reproduced the Clampett photo full size, so you can examine the room's contents closely if you wish; you can go to that large version by clicking on the smaller version above, or by clicking on this link.

"What Would Bob Do?"

That's the title of my essay about Bob Clampett and related matters that you can access by clicking here. The essay is an outgrowth of the discussion of Buckaroo Bugs and other Clampett cartoons that ran for a few weeks here last month. I remarked at one point that what I saw "in a great many posts praising Clampett's cartoons ... is a focus on details of direction and animation, at the expense of any serious examination of the films as a whole. In a number of cases, I think, it's much easier to praise a Clampett cartoon on the basis of those details than of the impression left by the entire film." I didn't explain then just what I meant, but I've tried to do so in this essay, with the help of some quotations from Hollywood Cartoons.

And Speaking of Clampett...

Kristin Thompson has written a highly enjoyable tribute to him on the Web site she shares with David Bordwell. Here's a quote about her response to Draftee Daffy, which she watched while in the midst of revising their textbook, Film History: An Introduction:

Kristin Thompson has written a highly enjoyable tribute to him on the Web site she shares with David Bordwell. Here's a quote about her response to Draftee Daffy, which she watched while in the midst of revising their textbook, Film History: An Introduction:

As I watched the film on DVD, I paused on a number of possible frames to use, and I found myself laughing out loud at almost every one—something that doesn’t often happen during the revision of a textbook. Some of the character movements in Clampett’s films are so fast and brief that they come across as a flurry of images too fleeting to register. Frozen, they reveal some of the extraordinary means that the director and his animators used to achieve those effects of speed. Clampett was also adept at highly exaggerated reactions and hilarious distortions of the animal body. Watching these cartoons with a finger on the pause button can yield hilarity and teach you a lot about normally hidden aspects of the art of animation.

She's absolutely right, of course.

March 2, 2008:

More on Walt in Hawaii

I've looked at some more microfilm from Honolulu, and it provided some fresh details about Walt and Lillian Disney's August 1934 visit to the islands. To go straight to the new material on my Essay page devoted to that trip, click here; or you can click here to start from the top.

...And Speaking of Disney

D. F. Faber sends along this link to a New York Sun article about a Disney-related gallery show that may be of interest to some of my more adventurous visitors.