"What's New" Archives: January 2008

January 31, 2008:

January 30, 2008:

January 29, 2008:

January 26, 2008:

A "Golden Age" Comic-Book Script

January 24, 2008:

Chuck Jones at the Drawing Board

January 22, 2008:

January 21, 2008:

Where Walt Was: Honolulu, August 1934

January 18, 2008:

January 17, 2008:

January 16, 2008:

January 15, 2008:

January 14, 2008:

January 13, 2008:

January 10, 2008:

January 9, 2008:

January 8, 2008:

January 7, 2008:

January 6, 2008:

January 3, 2008:

More on Satoshi Kon and Bob Clampett

January 31, 2008:

The Comic-Book Beat

More on Roger Armstrong and Chase Craig

My January 26 post, about Chase Craig's script for a Porky Pig story in Dell's Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies Comics, a script that Roger Armstrong illustrated, has prompted an illuminating post by Mark Evanier on the nature of comic-book writing and comic-book scripts.

I heard from Gordon Kent, who read Mark's post and was prompted to share his memories of Roger and Chase:

I met Roger back in 1974 or '75 when I was still in college. One of my art teachers knew him and arranged for me to drive to Laguna Beach to meet him. Roger's studio was in a trailer in a trailer park. It was strewn with art. We shared a cup of tea ("strained through our teeth") and Roger talked to me about his comic-book work and his watercolor work. Over those early years I was invited to a couple of his watercolor shows and I visited him a couple more times. He was the very first professional cartoonist I ever got to talk to. He was fascinating, encouraging and very generous with his time

In 1977 I was hired at Hanna-Barbera, and Chase Craig was also hired there to, among other things, create a Scooby Doo comic strip. I was one of two people assigned to Chase as a writer for the strip (Warren Greenwood was also assigned to this duty). Warren and I both did our writing as "scripts" and then he would sketch out my ideas and I sketched out his. (His were more detailed, mine were much rougher.) Oddly enough, the first person Chase hired to draw the strips was Roger Armstrong! The other person he hired to do the drawing was Dan Spiegle. Needless to say, the strip never sold. (I believe I have a couple of them in my office somewhere.)

The other odd piece of serendipity was that as I got to talk to Chase Craig I realized that I went to school and had classes with one of his sons, Bruce! I was in junior high Spanish with Bruce and, as a present for helping him out, he brought in a stack of comic books for me. It never occurred to me to ask where they may have come from.

At any rate, I want to thank you for posting that story. I'd never seen Chase's artwork before and it was really delightful to see it.

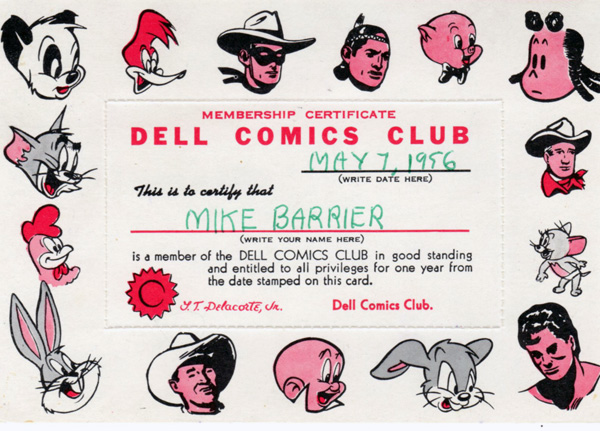

About that "Dell Comics Club" card...

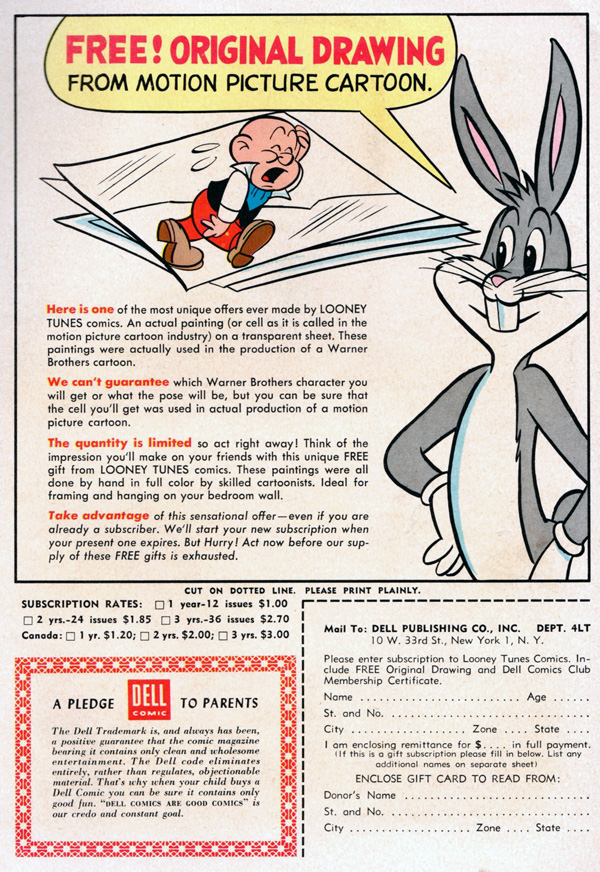

I got the card when I subscribed to Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies Comics in 1956 to get one of the more unusual premiums that Dell ever offered.

In those days, Dell encouraged subscriptions to its comic books; a dollar bought you a twelve-issue subscription to any of its monthly titles, which in 1956 included Looney Tunes, New Funnies, The Lone Ranger, Little Lulu, Tom and Jerry, Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, and Tarzan. (Walt Disney's Comics & Stories also went out under the Dell label, but the Disney characters weren't included in any of the blanket Dell promotions.) Not only did you get a 20-cent subscription discount versus the newsstand price, you also got a little gift. In the late '40s and early '50s, pinups of the Dell characters were the favored premiums, but by the mid-'50s, lots of other things were being offered: "push-button" pens, a key case, "magic puzzle" games, and so on. The premium changed every month, I suppose because Dell was picking up small lots of merchandise at bargain prices. But the premium offered on the inside back cover of the April 1956 Looney Tunes (seen below) was very different, and very special: a cel from a Warner Bros. cartoon.

The offer was described this way:

Here is one of the most unique offers ever made by LOONEY TUNES comics. An actual painting (or cell as it is called in the motion picture cartoon industry) on a transparent sheet. These paintings were actually used in the production of a Warner Brothers cartoon.

We can't guarantee which Warner Brothers character you will get or what the pose will be, but you can be sure that the cel you'll get was used in actual production of a motion picture cartoon.

The quantity is limited so act right away! Think of the impression you'll make on your friends with this unique FREE gift from LOONEY TUNES comics. These paintings were all done by hand in full color by skilled cartoonists. Ideal for framing and hanging on your bedroom wall.

I didn't subscribe to comic books then—I hated the way the comics were always folded and creased in the mail—but I couldn't pass up a chance like this. My cel arrived in due course; it was of Sylvester, who was holding a club over his shoulder and wearing a sheepish expression. I'm sure I identified the cartoon it was from at some point, but I no longer remember. The cel was, unfortunately, badly damaged in the mail, with a lot of the paint knocked off; a lot of other cels probably suffered the same fate, and I wonder now if Dell had to field a lot of complaints. How many of those cels were there? How many have survived? (Mine vanished long ago.) Have any turned up on eBay? It would be interesting to know.

I wonder too about the economics of Dell's subscriptions and especially its premium offers. Even given how much more a dollar bought in the '50s than it buys now, how much lower postal rates were, and how little the people opening the subscription envelopes were paid, I still can't imagine how Dell made money off its subscriptions. Were there enough subscriptions that their volume—and the predictability they brought, to press runs in particular—was sufficient to make them a paying proposition? Walt Disney's Comics had a lot of subscribers, I'm sure; it seemed that all my friends had subscriptions when I was a kid, and I was thrilled when I finally got one for my ninth birthday. But I don't remember that anyone got New Funnies or The Lone Ranger in the mail.

And speaking of comic books...

A request from Dana Gabbard re: John Stanley, the Little Lulu writer/artist:

I am trying to put together an entry on comic book writer John Stanley for wikipedia, and I need the aid of some fans who have details about his career. My first attempt to seek aid, a request in a fanzine for Stanley fans, garnered no response. Maybe one of the readers of your site may be willing to help.

Dana can be reached at dgabbard@hotmail.com.

Honoring Ward Kimball

[An update: As Larry Varblow has pointed out, and I should have figured out for myself, Perris, California, has a very strong Kimball connection: "FYI, the City of Perris is the location of the Orange Empire Railroad Museum. Much of Ward’s railroad collection has been donated over the years to the museum along with funding to help preserve the collection. I would suspect this to be the major reasoning behind the tribute." Click here to go to the page about Kimball on the museum's site. I've borrowed the photo above from that page.]

[An update: As Larry Varblow has pointed out, and I should have figured out for myself, Perris, California, has a very strong Kimball connection: "FYI, the City of Perris is the location of the Orange Empire Railroad Museum. Much of Ward’s railroad collection has been donated over the years to the museum along with funding to help preserve the collection. I would suspect this to be the major reasoning behind the tribute." Click here to go to the page about Kimball on the museum's site. I've borrowed the photo above from that page.]

Also from Dana Gabbard, this link to a resolution by the city council of Perris, California, asking Riverside County to bestow Ward Kimball's name on the new downtown inter-modal transportation facility at Perris. Walt Disney's name has adorned any number of schools and parks over the years, but I'm not aware of similar honors for important Disney employees like Kimball. Perris is a city of about 50,0000 more than 60 miles southeast of Kimball's home in the San Gabriel Valley. I don't know of any direct Kimball connection with Perris, but Ward loved trains, as everyone knows, and Perris has a railroad history, according to Wikipedia: "The city is named in honor of Fred T. Perris, chief engineer of the California Southern Railroad; the California Southern connected through the city in the 1880s to build a rail connection between the present day cities of Barstow and San Diego." That's a good enough excuse to honor Ward's memory, I think.

January 30, 2008:

Where's Walt, No.4

Here's yet another intriguing photo of Walt Disney (love that hat!), this time with his wife, Lillian, and apparently on board a ship. The date and place are uncertain, but given how old the Disneys appear to be, and their winter-weight clothing, I'd guess this photo is from November or December 1946, when Walt made his first postwar trip to England and Ireland. (The suit may be the one he's wearing in the frontispiece to The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney.) I'm not sure yet which ship the Disneys were on when they crossed the Atlantic to England, but they returned on the Queen Elizabeth, arriving in New York on December 12, 1946.

Back on December 7, I expressed some frustration that we didn't know more about how Walt filled his days on his trips to Europe in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Diane Disney Miller, Walt and Lillian's daughter, has written to share her memories of some of those trips. She and her sister, Sharon, made their first trip to Europe with their parents in 1949:

My sister and I accompanied mother and dad on the trip occasioned by the making of Treasure Island, and two subsequent trips for the same purpose, the making of a film [The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men in 1951, and The Sword and the Rose in 1952]. It was our first trip to Europe. We sailed on the Queen Mary, with steamer trunks full of clothes—black tie every night on the ship. We were ensconced in the Savoy Hotel. Room service was prepared by the waiters on the floor in a tiny kitchen. Dad spent most days in London on the set, and had many press meetings, interviews, etc., some in our hotel suite. Mother, Sharon, and I wandered around London. Saw everything we should see, and then followed mother in and out of antique shops on Beauchamp Place. Dad did some shopping of his own, the beginnings of his miniature collecting.

On weekends we would go into the country—Windsor Castle, Hampton Court, Canterbury. That first summer we went way up to Drumnadrochet, Scotland, home of the Loch Ness monster. Each time we went we took a family trip to the continent—Paris, Rome, day trip to Naples. It was different every time. It was all wonderful. Dad was a lot of fun to travel with. We did see that damn Strasbourg clock the first summer, a funny story. He had discovered it when driving people around back in 1918, and was very intrigued with it. The clock in the facade of the Small World ride is the result.

We went to Ireland twice, I believe. Mother and dad loved going there, and had some very good friends, Bertie and Vogue McNalley, who was with the RKO office, and his sister and brother-in-law. Bill Walsh went with us once, to Ireland. It was so much fun, always.

When the QE2 had its gala voyage some years ago a very good friend of my sister's was on it. She sent me a photo of herself standing in front of a life-size photo of mom, dad, Sharon, me, all dressed up for dinner, that was by the door to the dining room.

Walt traveled frequently, usually with Lillian, and from all I can tell, he enjoyed his trips a great deal, with no hint of compulsive wandering or anything of that sort. He enjoyed travel even when it was in many ways more difficult and complicated than it is today, as in the '30s and '40s. Crossing the country then required several days on the train, and crossing the Atlantic even longer on an ocean liner. Air travel wasn't a terribly attractive option—it was new, relatively hazardous, and expensive, and yesterday's propeller-driven planes were a lot slower than today's jets. Money and fame can smooth out many of the wrinkles in travel, of course, and I'm sure they served that purpose for Walt, but he still seems to have enjoyed travel for its own sake, as Diane Miller's memories suggest. I can readily understand that. Some of my own happiest memories are of walking the streets of wonderful cities like London and Paris and Barcelona with my wife; but to have been Walt Disney and visiting such places with your wife when your worldwide fame was cresting—well, that had to have been a very special experience.

Meanwhile, in Nutziland...

Walt and Lillian Disney made one long trip together to Europe before World War II, in 1935, with his brother Roy and Roy's wife, Edna. The Disneys stopped briefly in Munich on that trip, a visit that served as the pretext for John Powers's bizarre play Disney in Deutschland. Harry McCracken and I both wrote about this play last June, when it was first produced in San Francisco, and Harry actually saw it. Now it is going to be staged again, starting tomorrow, as I learned thanks to this link from Are Myklebust. Powers is still making the same broad and unsupported charges. I wish I could understand why Walt attracts so much hostile attention from such people, and why other people, who should know better, take cranks like Powers seriously.

January 29, 2008:

More on Chuck Jones

To continue my January 26 discussion of Chuck Jones's disappointing later work, and at Mark Mayerson's suggestion, I'm posting scans of the two-page essay on Jones's career that I wrote for Funnyworld No. 13 in 1971. On his own site, Mark has republished his excellent 1995 essay about the unfortunate changes in Chuck's work in the years after he left Warner Bros.

To continue my January 26 discussion of Chuck Jones's disappointing later work, and at Mark Mayerson's suggestion, I'm posting scans of the two-page essay on Jones's career that I wrote for Funnyworld No. 13 in 1971. On his own site, Mark has republished his excellent 1995 essay about the unfortunate changes in Chuck's work in the years after he left Warner Bros.

As my Funnyworld piece indicates, I think those changes were well under way by 1971. Mark Colangelo agrees, and he has written to make a too easily overlooked point: Chuck wasn't very old when his drawings began to change for the worse.

I read the comments on Chuck Jones's decline recently, and it seems most people blame it on age. However, Jones started the slow decline in the late fifties, while still at Warners. (It's not so bad during that era, but the seed of what's to come was planted back then.) He was middle-aged at that time, in his forties. It seemed like the strange drawing style was a conscious choice on his part. Of course, old age didn't help Jones's slow decline, but I don't see it as the root cause. The question is, how did such an amazing draftsman completely lose the ability to make the appealing drawings he used to be known for?

Chuck celebrated his fiftieth birthday in 1962, the year he left Warners. He wasn't exactly senescent then, or ever.

I wish that Chuck's work in his later years showed the artistic growth whose absence Mark Mayerson correctly points out. Perhaps ego was the villain here. Of all the animation people I've known, only Chuck and Ralph Bakshi, when I knew them, seemed to have full-blown "Hollywood egos" of the Jerry Lewis variety, and I think that egotism pushed Chuck toward celebrating and trying to repeat his past successes. He knew that his audience would follow him, if only out of affection for the truly wonderful films he'd made decades earlier, whereas he risked losing that audience if he reached into himself for something more substantial. Perhaps his jarring experiences with The Phantom Tollbooth and then with the ABC show Curiosity Shop confirmed Chuck in a determination to hew as closely as possible to what he'd done before. The burgeoning interest in his Warner cartoons in the 1970s can't have discouraged him in any such resolve.

The sad thing is, Chuck showed tremendous artistic growth and maturity when he was making his best films. Over and over again, he risked the most embarrassing sort of failure: having a studio audience respond to his departure from formula by sitting on its hands. He deferred to the strengths of his most important collaborator, Mike Maltese, instead of regarding Maltese's talents as a threat to his own preeminence. In his greatest years, roughly 1945-55, Chuck seems to have understood how good his cartoons could be, and to have focused all his efforts on making them that good. The Chuck Jones of those years is one of the two or three most admirable figures in Hollywood animation's history, and I wish I could have known him then. The Chuck Jones I knew, starting in 1969, was less admirable, and by the time I last saw him, in 1986, there was not much left to admire, at all.

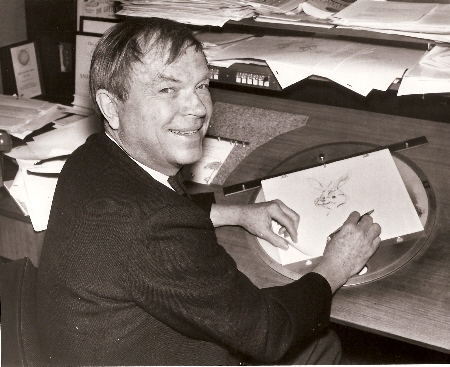

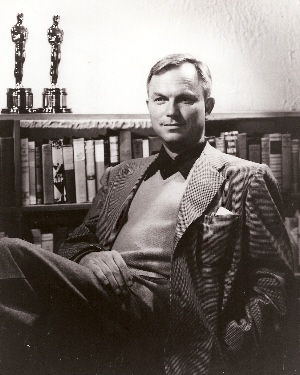

The accompanying photo was probably taken in 1950, after two cartoons Chuck directed or co-directed—For Scent-imental Reasons and So Much for So Little—won Oscars. Chuck turned 38 that year.

Joe Grant and Hero Worship

My January 26 post about Chuck Jones began as a response to a couple of posts by Will Finn. My remarks provoked extraordinarily intense attacks by Finn against me, first in a post on his blog and then in his responses to visitors' comments. His post is under the heading "Barrium"—a pun intended to evoke barium enemas, of course. In reading what Finn has written, I think I've finally figured out that he's particularly angry about what he regards as my mistreatment of Joe Grant in Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age.

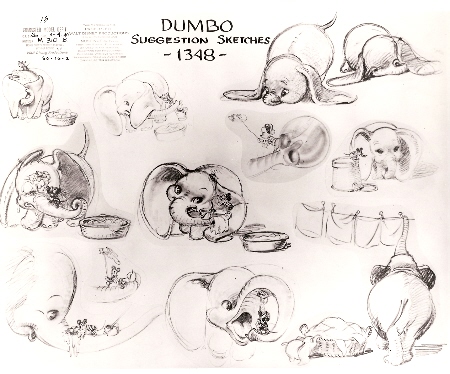

Joe was one of the Disney studio's mainstays in the 1930s and 1940s, with prominent (and well deserved) credits on landmark features like Fantasia and Dumbo; thus "OK by JG" on sheets like the one above for Dumbo, by Albert Hurter. He was also controversial, regarded by many of his colleagues as patronizing and manipulative (Joe called himself "Machiavellian"). Dick Huemer, Bill Peet, and Ward Kimball, among others, spoke critically of Joe to me and Milt Gray in interviews. I first met Joe in 1978, and I saw him on perhaps a half dozen occasions after that, but his interest in me and my book seemed to decline rapidly after he returned to work at the Disney studio in 1989. For my part, I was uncomfortable with my increasing awareness of the side of Joe's personality that annoyed his colleagues.

I last saw Joe in 1991, not for an interview but when Milt and I took him to dinner soon after the death of his wife of many years, Jennie. In 1993, I put the National Portrait Gallery in Washington in touch with Joe so that some of his drawings could be included in a huge show devoted to celebrity caricatures (the curators loved him as well as his drawings), but that was the end. I didn't send him a copy of Hollywood Cartoons when it was published in 1999. We had been out of touch for years by then, and his indifference to the book (or maybe his doubt that it would ever be finished) was so pronounced by the early '90s that I wasn't at all sure he'd even be interested in it. Besides which, it was costing me around $35 each to mail out complimentary copies of the book, and I had very quickly run up a tab approaching a thousand dollars. But I should have sent him one, anyway.

Joe was, to me, one of dozens of exceptionally interesting and enjoyable people I met who worked in the Hollywood animation studios in their heyday. By the time Joe returned to the Disney studio, though, he was one of the very few survivors of that heyday, and he evidently impressed his much younger colleagues, of whom Will Finn was one, as an emissary from a magical golden age. For me to have written about the very real human being he was in the '40s—in some ways admirable, in other ways less so—as I did in Hollywood Cartoons, must have seemed blasphemous to many of those younger colleagues. I doubt that Joe discouraged such responses.

Hero worship is a widespread disease in the Hollywood animation community, and Finn's "Barrium" appears to be the product of a particularly virulent strain of that disease. My review of the Disney feature Home on the Range, which I've posted here since 2004, may not have helped, either. Finn co-wrote and co-directed Home on the Range, with John Sanford. I should have mentioned both of them in my review, no matter what I thought of the film.

A reminder: you can read one of my interviews with Joe Grant, and hear an audio clip from it, by clicking this link. I've made copies of all of my Grant tapes available to Don Hahn for possible use in a film he's making that will be a tribute to Joe. I'm looking forward to seeing it.

January 26, 2008:

A "Golden Age" Comic Book Script

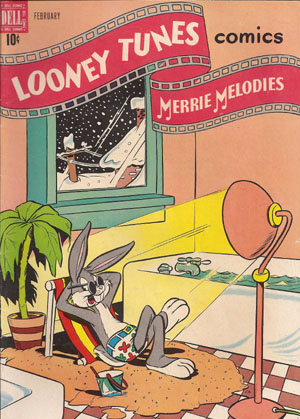

With all the talk of scripts recently, on this site and others, it seems like an opportune time to share a script of another kind, not for a "golden age" cartoon but for a comic book based on some of those cartoons. If you click on this link, you'll go to an introductory Essays page that will take you in turn to the twelve-page script for the Porky Pig story in the February 1949 issue of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies Comics, written by Chase Craig, and to the published story itself, drawn by Roger Armstrong. Roger gave me this script many years ago.

With all the talk of scripts recently, on this site and others, it seems like an opportune time to share a script of another kind, not for a "golden age" cartoon but for a comic book based on some of those cartoons. If you click on this link, you'll go to an introductory Essays page that will take you in turn to the twelve-page script for the Porky Pig story in the February 1949 issue of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies Comics, written by Chase Craig, and to the published story itself, drawn by Roger Armstrong. Roger gave me this script many years ago.

I've called what Chase Craig did a "script" for lack of a better term, even though he told his story in extremely rough sketches that evoke a storyboard. But "storyboard" doesn't quite fit, either, since Craig was concerned not just with the essentials of the story and the dialogue but with breaking the story down into panels and staging the action, the rough equivalents of what an animation layout man and director would have done back in the '40s. To complicate matters further, Roger Armstrong restaged the action in a number of panels, as well as drawing the characters with far more refinement than Craig did in his sketches.

So, "script" it is, although I won't quarrel too violently with anyone who wants to use a different name for what Chase Craig did. I'm jealous, actually, that Craig was able to draw his story, rather than describe the action and the settings in words. For my own limited foray into paid comic-book scripting, the ten-page Donald Duck story hat was eventually published in the U.S. in Donald Duck and Friends in 2003, I had to write a true, no-kidding script, all in words and with detailed descriptions of everything. It wasn't a lot of fun, and I haven't pursued other such scripting opportunities very aggressively.

January 24, 2008:

Chuck Jones at the Drawing Board

Will Finn ignited an interesting discussion on his blog, one that spilled over to Cartoon Brew, when he suggested that maybe the drawing in Chuck Jones's gallery work of the 1970s and afterward was inferior to Chuck's brilliant character layouts of a few decades earlier: "As cool as it was to see new art by the old master ... a lot of it began to look stiffer and creakier as time wore on, as if not only the artist, but the characters themselves were slipping into stodgy old age."

The comments on both blogs have had an Emperor's New Clothes quality, with a few idolators insisting fervently that Chuck's stuff was always rilly, rilly great, and others endorsing Finn's remarks, but with an eye on the nearest exit. Finn himself has now put up a second post in which he all but flays himself for putting up the first one:

I never intended to slight or disrespect Chuck Jones and I regret giving that impression. ... I am beginning to wonder if it is best not to offer critical comments at all in such a public forum [where] there is plenty of room to be misunderstood. I don't mean to set myself up as the standard bearer for the industry and would be on pretty thin ice if I did. ...

Second, despite my dislike for much of the later gallery art, I do not mean to suggest that Mr. Jones was "hacking" when he did this stuff. I think rather he did these to what he believed was the best of his ability and it should go without saying it was in his discretion to do them in any style he chose. He was a classy guy and I don't think "hacking" was in his nature.

I've written here before about the tendency of animation blogs to limit themselves to "shop talk"—shallow chit-chat, technical tips—out of the bloggers' fear of giving offense to colleagues or potential employers (who are often the same). I can't speak to Finn's motives, but his second post reads like a particularly sad example of what I had in mind. He was right the first time: Of course Chuck's later stuff—film and gallery art alike—is inferior to his great work of the '40s and '50s. If the earlier work is good, comparison alone dictates the conclusion that the later work isn't.

I'm sure Chuck knew that was the case, even though he never advertised the fact. When he was appearing at colleges and museums and the Kennedy Center (where I saw him several times) in the '70s and '80s, he never showed any of his recent films; instead, he showed Warner cartoons he'd made twenty-five and thirty years earlier. He knew they were the foundation of his reputation; he knew that's what his audiences wanted to see.

As for Chuck's slack and lazy gallery pieces, they were just souvenirs, having no more connection with the real Chuck Jones, the master who made many of the greatest American short cartoons, than a tabletop miniature of the Empire State Building has with the real structure. By buying a hokey cel setup, a fan could take home a sliver of Chuck Jones, like some medieval pilgrim buying a piece of the True Cross—except that there was never any pretense that anything was genuine about the cel setup except Chuck's signature. No one was fooled, unless they wanted to be; and if through those souvenirs Chuck finally made back some small part of the fortune he'd earned for Warner Brothers, so much the better.

The interesting question is not whether Chuck's drawings deteriorated, starting in the late '50s, but why. I've laid out some of my own thoughts about that question in Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, on pages 539-43, and I won't rehash them here. But I still think they're on target.

My 1969 interview with Chuck, from Funnyworld, is still available at this link.

Speaking of Scripts...

The online controversy over the use of scripts for "golden age" cartoons has died down, I'm sure because the blowhards denying the existence of such things were confronted with so much evidence to the contrary that they had to give up trying to explain it away. But to nail the coffin shut, Hans Perk has offered a excerpt from Donald Graham's unpublished "Art of Animation" manuscript from 1955, in which Graham talks at length about the useful role that scripts played in story work at the Disney studio up into the 1950s. I have a copy of that manuscript, and I've read it more than once, but I'd forgotten about the passage Hans quotes, and I'm grateful he brought it to light.

There is, as always, much more on Hans's site that's worthy of your attention. No one else, not even Didier Ghez, is posting so many important Disney documents, especially the "drafts" showing who animated which scenes on both features and shorts.

Hans quotes Walt as supposedly saying of Graham's manuscript, "If we publish this, everyone can make animated features!" That's got to be apocryphal, or at least tongue-in-cheek. I'm sure Walt was most concerned, with this book as with his TV show, about accessibility, about entertaining a broad audience, even at the cost of rounding a few corners. But he cared about accuracy, too. When Graham's manuscript eventually metamorphosed into Bob Thomas's 1959 book Walt Disney: The Art of Animation (shown above), Walt went over Thomas's manuscript and added comments in his distinctive hand-printing.

The Thomas book is still one of my favorites. I bought it when it first appeared, read it and underlined it ardently, and bought a second copy (which differs slightly from the first printing) a few years later, so I'd have one copy that wasn't badly mangled by my enthusiasm. I have the revised edition from 1991, too, but I much prefer the original, with its echoes of Walt's presence, the faint sense that he was looking over the author's shoulder.

January 22, 2008:

More on Walt in Hawaii

[I've appended this short item to the Essays page on Walt Disney's August 1934 trip to Hawaii.]

Links and Updates

Aardman: Kristin Thompson, whose film blog with David Bordwell is one of the ornaments of the online world, has written to alert me to a new post on that site about the Aardman animation studio: "I’ve been surprised at the lack of an adequate chronology/filmography on the company, so I’d tried to cobble one together. It ended up taking much longer than I expected. I’m sure you and other experts will spot all sorts of errors and omissions, but at least it’s a start."

Aardman: Kristin Thompson, whose film blog with David Bordwell is one of the ornaments of the online world, has written to alert me to a new post on that site about the Aardman animation studio: "I’ve been surprised at the lack of an adequate chronology/filmography on the company, so I’d tried to cobble one together. It ended up taking much longer than I expected. I’m sure you and other experts will spot all sorts of errors and omissions, but at least it’s a start."

I'm no Aardman expert, but what Kristin has posted looks awfully good to me. And while you're visiting the Bordwell-Thompson site, you may—you should—want to read David's piece on Walt Disney and their dialogues on Beowulf and Ratatouille, among many other things.

Amazon.com: Many thanks to the two dozen or so visitors to this site who either posted reviews of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney on amazon.com or gave an unfavorable rating to Patricia Block's bizarre diatribe against the book. Block has still not provided a page citation for the anti-Walt quotation she claims is from my book; no surprise there.

B. Baker has shared with me a fascinating piece on slate.com about the strange culture of which amazon.com's top reviewers are a part. Forty-five reviews a week does seem a bit unbelievable, no?

"Virtual Worlds": I'm unconscionably late in posting this link to a New York Times piece about "virtual worlds"—Bill Benzon called it to my attention weeks ago—but, fortunately, the piece is still available. The animation/comics connection is obvious in paragraphs like this one:

Disney last month introduced a “Pirates of the Caribbean” world aimed at children 10 and older, and it has worlds on the way for “Cars” and Tinker Bell, among others. Nickelodeon, already home to Neopets, is spending $100 million to develop a string of worlds. Coming soon from Warner Brothers Entertainment, part of Time Warner: a cluster of worlds based on its Looney Tunes, Hanna-Barbera and D. C. comics properties.

I'm a hopeless old fogey (as you're well aware if you've spent much time at this site or have read my books), but I can't help but regard "virtual worlds" as skeptically as I've always regarded video games. The problem for me, in both cases, is that the participants in the "worlds" and the games are in effect being invited to take control of stories, even though their talents as storytellers are almost certainly inferior to the talents of, say, the people who made the Looney Tunes that are being used as raw materials.

As a child, I struggled to tell my own stories, but I was inspired by the examples of Carl Barks and Walter R. Brooks and Walt Disney, among many others; I wasn't entering into someone else's story and tinkering with it, and it seems to me that a lot of game- and role-playing amounts to nothing more than that. It's a lucky kid today who reads a wonderful book or sees a wonderful movie and comes away fired up with the desire to make something just as good. If that kid spends his time playing video games or in "virtual worlds" instead, he's impoverishing his imagination.

January 21, 2008:

Where Walt Was: Honolulu, August 1934

[I've moved this piece to a separate Essays page, at this link.]

January 18, 2008:

Hanna-Barbera: Jaime Weinman has joined the discussion with an excellent post that is perhaps a little more sympathetic to H-B than Mark Mayerson, Michael Sporn, and I have been, although without descending into the nostalgic reverie that comes all too easily to many people who watched the H-B cartoons as children. Jaime has been making good use of newspaperarchive.com, I'd guess, judging from the obscure but fascinating quotes he has found from Bill Hanna and, of all people, Bob Clampett.

Kansas City: Almost three years ago, I visited the Disney sites in Kansas City and posted a photo essay on my visit. At that time, the McConahy Building, where Walt had his Laugh-O-gram studio, was in an advanced state of ruin. Louis J. Tofari wrote this week to say that things have been looking up since I was there:

I came across your site today, and thought that you might be interested to know that the building that housed Walt Disney's former Laugh-O-gram studio has been substantially reconstructed since your last visit. All four walls have been restored (and well done at that), the wall jacks are gone as are the plywood boards (one can actually walk on the sidewalk again).

By the way, I actually live and work in the neighborhood myself (my office is literally a block and a half away from the McConahy Building), and though it is definitely a recovering neighborhood, I would not go so far as to call it a "blighted" neighborhood (at least not anymore), while just around the corner, Troost Avenue is slowly being revived, a store front at a time.

I've checked the Web site of "Thank You Walt Disney," the organization that has undertaken the restoration of the building, and, unfortunately, I couldn't find any good photos there reflecting the progress Louis describes. I'm sure that my intense skepticism about Neal Gabler's Disney biography and Leslie Iwerks's biography of Ub have made me persona non grata with the people running that organization, but perhaps some of the Disney-themed sites can wangle good current photos from Dan Viets and his colleagues.

Amazons Attack!: Patricia Block has also posted her violently hostile review of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney on Barnes & Noble's Web site. She's obviously on a mission; I wish I knew why. I've submitted a comment to amazon.com myself, asking that she identify the page of my book on which a disparaging remark about Walt that she quotes appears.

January 17, 2008:

More H-B Talk

The publication of Jerry Beck's Hanna-Barbera Treasury has stimulated a lot of posts about that studio's cartoons, here and elsewhere, but Michael Sporn's post yesterday is particularly enjoyable. Michael watched the early H-B cartoons as a kid, and he's illuminating about how H-B affected him:

The publication of Jerry Beck's Hanna-Barbera Treasury has stimulated a lot of posts about that studio's cartoons, here and elsewhere, but Michael Sporn's post yesterday is particularly enjoyable. Michael watched the early H-B cartoons as a kid, and he's illuminating about how H-B affected him:

"Maybe a cactus appeared on the bicycle pans, and I got to recognize what a bicycle pan was (without knowing the term). Essentially I was picking up some animation cheats without doing more than watching. ... Looking back now on all that limited animation history, I have to say that I learned the tricks—probably many of them before I learned the right way to do it. I also got to realize that H&B truly flattened out the animation in ways that UPA and Kimball’s limited animation didn’t do."

How many other aspiring animators, I wonder, were affected in the same way, learning bad habits before they ever picked up a pencil professionally? And how many of those animators look back on H-B fondly now, with little or no awareness of how much they were damaged by the bad cartoons they loved as kids?

Michael Sporn himself eventually worked for Hanna-Barbera as an animator: "For a short time H&B and Ruby Spears farmed animation to New York animators. I picked up a lot of work and was able to animate and assist about 200 feet a week. They liked my stuff, and I made a lot of money in a short amount of time. Weeks later my shows would be on TV, and I couldn’t identify ANY of the scenes I did. It was all so forgettable. It was about making quick money, and I hated it. I quit and started my own company."

At least we can be grateful that H-B inspired Michael to take that step.

Amazons Attack!

(Puns are treacherous. I've just discovered that's the title of a graphic novel starring Batman and Wonder Woman.)

The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney will be out in paperback in less than three weeks, on February 4. Probably it'll be available from amazon.com and other vendors a few days before the official date. Unlike the paperback of Neal Gabler's Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, the paperback of my book will include corrections of the errors I identified in the hardcover—not a lot, but enough that I'm glad to have had the opportunity to fix them. Thanks to a technical glitch, the amazon.com page had no picture of the paperback's cover until this week, but that lack has finally been remedied.

The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney will be out in paperback in less than three weeks, on February 4. Probably it'll be available from amazon.com and other vendors a few days before the official date. Unlike the paperback of Neal Gabler's Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, the paperback of my book will include corrections of the errors I identified in the hardcover—not a lot, but enough that I'm glad to have had the opportunity to fix them. Thanks to a technical glitch, the amazon.com page had no picture of the paperback's cover until this week, but that lack has finally been remedied.

When I'm buying something from amazon.com, I usually don't pay a lot of attention to the customer reviews. As with the comments on blogs, you often have to wade through a lot of junk to get to the good stuff. There are exceptions—the more serious the subject of the review, the better the odds that the review will be worth paying attention to. For example, I've found the reviews of electronics and classical-music CDs helpful on more than one occasion. But when it comes to animation, and books about animation and animators, there's no telling what will turn up. And when your own book is the target of one of the wacko reviews—ouch!

The hardcover edition of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney has received only a few reviews on amazon, but all of them were very favorable until about two weeks ago, when Patricia Block, who labels herself "disneylandcrazy" (she's apparently a marketing consultant in northern California), posted a one-star review overflowing with bile. The heading is "Want your Disney heart ripped out?" It goes downhill from there. I've not seen a review of the book so vicious and wildly inaccurate since the Library Journal ran its negative review by a Star Trek fan. Block includes what is supposed to be a damning direct quotation from the book, but I don't recognize it, and I haven't been able to find it.

I doubt that Block's review will do as much damage to the book's sales as the Library Journal's review seems to have done, but it can't help, either, especially considering how hard it has been for my book to get noticed in the shadow of Gabler's heavily publicized Disney biography. I've always been reluctant to ask for positive amazon reviews of my books, although I've suggested to a couple of people who wrote to me favorably about The Animated Man that they might put those same thoughts into an amazon review. Block's review encourages me to think that asking for praise might be the lesser of evils.

So: if you've read The Animated Man and you liked it, please think seriously about posting a short review at amazon.com—or, for that matter, Barnes & Noble's site, bn.com, where the sole customer review, a highly favorable one, was posted by Michael Broggie, who actually knew Walt, and whose father, Roger, was instrumental in the creation of Walt's backyard railroad.

January 16, 2008:

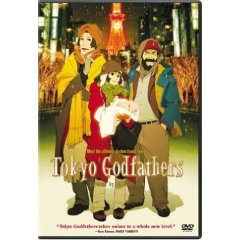

Tokyo Godfathers

I've written favorably about the Japanese director Satoshi Kon on a couple of occasions, and there's a Feedback page devoted to his four animated features. I saw my third Kon feature, Tokyo Godfathers (2003), the other day, on DVD, and I enjoyed it. The debt to John Ford isn't terribly obvious, and the story, about an oddly mixed trio of street people and the abandoned baby they find, is imaginable as live action (or a graphic novel) but works perfectly well as animation. But here's what really surprised me.

I've written favorably about the Japanese director Satoshi Kon on a couple of occasions, and there's a Feedback page devoted to his four animated features. I saw my third Kon feature, Tokyo Godfathers (2003), the other day, on DVD, and I enjoyed it. The debt to John Ford isn't terribly obvious, and the story, about an oddly mixed trio of street people and the abandoned baby they find, is imaginable as live action (or a graphic novel) but works perfectly well as animation. But here's what really surprised me.

I saw Tokyo Godfathers just a few days after I finally saw Brokeback Mountain, also on DVD. I expected to find Brokeback moving and disturbing, but I came away thinking, "There sure was a heap o' actin' in that movie." So much actin', in fact, that I had a hell of time understanding what Heath Ledger was saying, thanks to his overlay of a Wyoming accent (I suppose) on his native Australian accent. But, mainly, despite all that actin', I couldn't believe a minute of it, except when Michelle Williams was on the screen.

I didn't have that problem with Tokyo Godfathers, despite the usual limitations of Japanese character animation (stiff, except when an emotional outburst is accompanied by wild facial distortions). The characters were distinct, interesting, and plausible, their lives full of the lies and evasions you'd expect from people reduced to living on the street; the story, with its twists and turns and surprises, held my attention and never went off the rails; and there was always the sense that the action was taking place in a real and unmistakably Japanese big city in the depths of winter.

It would hard for me to argue that Tokyo Godfathers was a "better" movie than Brokeback Mountain, and impossible for me to argue that it was a more "important" movie. But I certainly enjoyed it a lot more. I'm still trying to figure out what that means, about me and the movies.

January 15, 2008:

From Script to Screen

Keith Scott, the Australian voice artist and voice authority, wrote in regard to yesterday's item about the dialogue script for Chuck Jones's Rabbit Fire:

Keith Scott, the Australian voice artist and voice authority, wrote in regard to yesterday's item about the dialogue script for Chuck Jones's Rabbit Fire:

Mel probably did ad-lib at the Rabbit Fire session, but as you note he delivered the final dialogue as per script. From my thirty years of cartoon voice experience there's always a degree of improvisation to animation voice recording, so as to get a couple of variations in the line readings. I recall Bob Clampett saying he would get a few takes that would be "dailies," which he would listen to and then choose the best take.

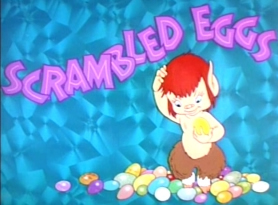

I have a definite dialogue script (i.e., not a transcript of the finished cartoon) for Lantz's Scrambled Eggs from 1939 which I copied at UCLA, because it had actor identifications for each line ("Dave," "Sarah", "Marge" and "Vic"—there were many one-liners in that cartoon and this has original dialogue with pencilled-in changes). The names stood for Dave Weber, Sara Berner, Margaret McKay, and writer Victor McLeod (who obviously did a few incidentals a la Ted Pierce).< face="Arial">

(The frame grab of the title for Scrambled Eggs is from the Walter Lantz Cartune Encyclopedia.)

Jeff Watson also wrote, about the abundant evidence that real cartoon scripts were in use at the Disney studio and elsewhere long before the date (1960) Stephen Worth has claimed for scripts' introduction into cartoon production:

< face="Times New Roman" size="3">While comparing the DVD versions of Sky Scrappers [a 1928 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoon] and Building a Building [a 1933 Mickey Mouse cartoon based on the Oswald cartoon], I noticed this discussion in Merritt and Kaufman's Walt in Wonderland, p. 98, bottom two paragraphs:

< face="Times New Roman" size="3">

< face="Times New Roman" size="3">"In addition to the drawings, a script was still prepared for each [Alice] film, and these were becoming more and more elaborate... By February 1928 he [Disney] was taking a whole page to describe the opening scene in Sky Scrappers." < face="Times New Roman" size="3">There is a bit of that opening scene description on page 28 of Walt in Wonderland, but there is no reproduction of the "script" in the book.

< face="Times New Roman" size="3">

< face="Times New Roman" size="3">

Also, unless I'm not understanding the terms used, I've seen examples of scripts in the Disney material for shorts in the '20s and '30s. Aren't the images on pages 30 through 32 in Pierre Lambert's Mickey Mouse the "script" for Steamboat Willie? The storyboard content in those sheets is marginal while the script text (descriptions of shots, action, sound effects, music, etc.) seems highly developed.

< face="Times New Roman" size="3">

< face="Times New Roman" size="3">However, as you've noted, strict terminology and unvarying practice were not the mode of operation at the Disney studio (and other places) in the late '20s and early '30s: the difference between Sky Scrappers and Building a Building demonstrate the results of the developments and changes at the Disney studio.

That is indeed a complete script for Steamboat Willie in Lambert's lavish book. It differs in many details from the completed film (there's no parrot in the script, for example), so there's no confusing it with a document prepared after the fact. The script has been reproduced not just in Lambert's book, but elsewhere, as in the big laserdisc set of black-and-white Mickey cartoons and in the first Walt Disney Treasures DVD set of black-and-white Mickeys.

January 14, 2008:

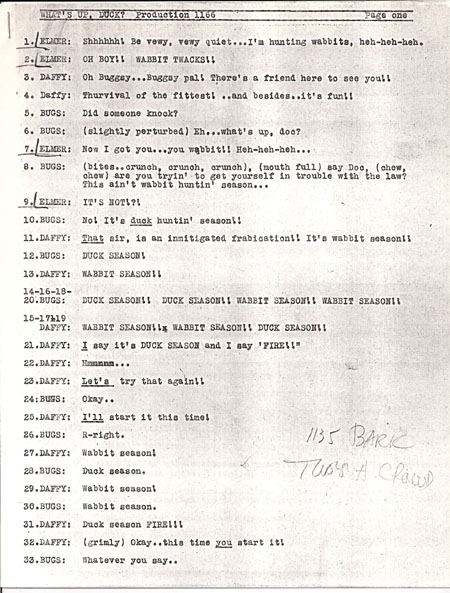

"You're Despicable!"

Yesterday I posted a page from the dialogue script for Chuck Jones's Rabbit Fire (1951), the first cartoon in the so-called "hunting trilogy," three cartoons in which Bugs Bunny outmatches both Elmer Fudd and Daffy Duck. Jones spoke of that cartoon as a rare example of Mel Blanc's ad libbing for a Looney Tune, telling me in 1976 that he had told Blanc at the recording session that Daffy at one point is so frustrated "that he can't think of any word except 'despicable.' ... Mel could carry on once he got the rhythm of it." Jones said much the same thing in a Film Comment interview published early in 1975.

Yesterday I posted a page from the dialogue script for Chuck Jones's Rabbit Fire (1951), the first cartoon in the so-called "hunting trilogy," three cartoons in which Bugs Bunny outmatches both Elmer Fudd and Daffy Duck. Jones spoke of that cartoon as a rare example of Mel Blanc's ad libbing for a Looney Tune, telling me in 1976 that he had told Blanc at the recording session that Daffy at one point is so frustrated "that he can't think of any word except 'despicable.' ... Mel could carry on once he got the rhythm of it." Jones said much the same thing in a Film Comment interview published early in 1975.

Presumably it happened that way, Blanc ad libbing at Chuck's direction, but what we hear in the finished film, as Daffy struggles to go beyond "you're despicable," is what is in the dialogue script. Chuck had two copies of that script in his files in January 1979, when he permitted me to copy such documents as part of the research for my ill-fated art book on the Warner cartoons (a book that was designed to rival The Art of Walt Disney but was never published because of the cost). The script is definitely a script, rather than a transcript of the recorded dialogue, because it differs in small ways from the film; for one thing, Jones cut a couple of Elmer's lines.

I'd guess that Blanc did in fact ad lib, as Jones remembered, but that he also delivered the dialogue as written—and it was that version that Jones chose to use in the film, contrary to his later recollection. Chuck probably made the right choice; Blanc was a wonderful voice actor, the best ever for cartoons, but I've never seen or heard anything to suggest that he was exceptional as an improviser.

January 13, 2008:

Talkin' H-B, Cont'd

Ray Kosarin and Gene Schiller have written to take the side of the Hanna-Barbera cartoons, against me and some others who have found them a negative influence on Hollywood animation. You can read their contributions to the debate on the Hanna-Barbera Feedback page.

Words and Pictures, Cont'd

A visitor to the site who prefers to remain anonymous writes as follows, in response to the controversy over cartoon scripts that I wrote about on January 10 (and in earlier posts):

I've been reading with interest the debate between blogs regarding whether classic cartoon writers occasionally used scripts. I don't have much to add since I'm not an animation historian, but I think that continuities, scenarios, outlines, and treatments should be excluded as examples of scripts. I think only actual finished scripts should be used as evidence. A "willingness to use the written word" is not the same thing as working from a full-fledged script. (Bob Jaques's example from the Famous Studios Superman cartoon certainly looks like a script to me, for example.)

When I last looked at the definitions of scripts, scenarios, and so on, in standard and literary dictionaries, I found a lot of vagueness and overlap. I don't think there's much to be gained in trying to categorize pieces of writing as scripts or not. A general outline might suffice as a script for live-action films of certain kinds, whereas in other cases a detailed shot-by-shot script might be called for. We've all heard of notorious cases, as with John Huston's Beat the Devil, where a script was being written even as a film was being shot, and I suspect that such scripts were skeletal at best. The critical question, where animation is concerned, is this: Did the people making a cartoon start by putting their ideas into writing, in substantive form (that is, more than just a cryptic note), or did they start with drawings?

Sometimes, as with the Warner cartoons of the 1940s and 1950s, the drawings unquestionably came first. When a Warner script has survived, like this dialogue script for Chuck Jones's Rabbit Fire (then wearing a different title), it was obviously prepared after the storyboard was completed, for use in recording the voices of Mel Blanc and Arthur Q. Bryan:

But in many other cases, especially before the mid-1930s, cartoon makers started by putting their story ideas into writing—as detailed outlines, or as treatments, or as scripts—before they began making drawings. When they did start drawing, they rarely if ever put up boards telling a complete story. The Disney studio was the most advanced in its methods in the early 1930s, but it wasn't until 1934 at the earliest that storyboards became a normal part of work on the Disney cartoons. Early in that year, Walt wrote, in a memorandum to his employees, about a brand-new way to tell a story: "Instead of writing your story, you could present the entire idea with sketches, with a few notes below each sketch (when necessary), to explain the action. This would be an ideal way to present your story because it then shows the visualized possibilities, rather than a lot of words, explaining things that ... turn out to be impossible to put over in action."

(For a full account of the evolution of the Disney storyboards, see pages 97 and 115-16 of my Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age.)

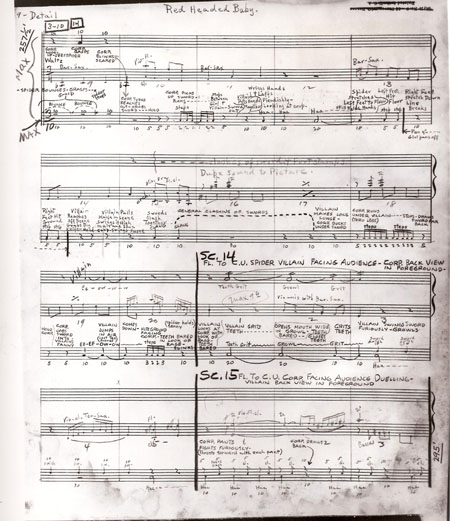

The storyboard was obviously a superior way to tell a cartoon story, and it didn't take long before it was a standard resource at the Disney studio, and then at other cartoon studios. But not all of them. Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising, throughout their careers in the 1930s as independents and then as MGM producers, worked out their stories less through story sketches than on bar sheets, with sketches serving as a sort of supplement. For an example of how a bar sheet could double as a sort of script, see the page below from the bar sheets for Ising's 1931 Merrie Melodie Red-headed Baby (click on this image or the previous one for a larger version) :

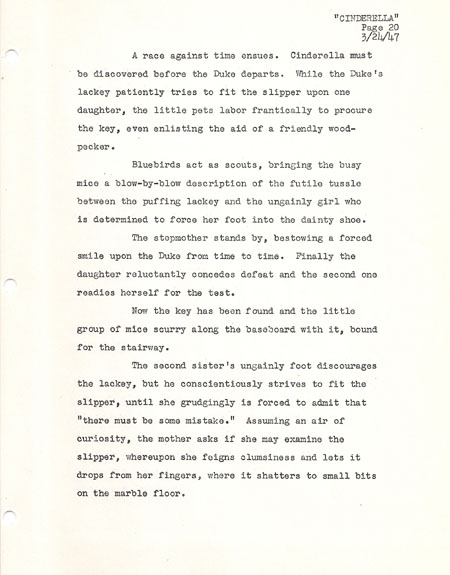

Even at Disney's, where the storyboard rose to a sort of perfection in the hands of brilliant artists like Bill Peet, treatments and other preliminary writings continued to be used heavily in work on the animated features. The 1947 treatment for Cinderella that I excerpted on January 10 was just one of many such treatments and outlines, for that film and others, including Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, and Sleeping Beauty.

Stephen Worth, who ignited the current controversy through his brazen contention that there were no cartoon scripts before 1960, has been forced to admit that yes, the Cinderella treatment is the sort of thing he claimed didn't exist. But Worth and some other alumni of John Kricfalusi's Spumco studio have been nothing if not igenious in suggesting how other documents might have been prepared after the story sketches for the cartoons in question.

Thus Eddie Fitzgerald has proposed that Bill Cottrell's 1934 script for Who Killed Cock Robin? could have been based on an early Leica reel (Disney didn't make Leica reels, which were film strips composed of story sketches, until 1938 at the earliest, and there's no surviving evidence that there was even a complete board for Cock Robin, much less a Leica reel ). Worth himself has declared that the script for the Fleischers' Surprise must be what he calls a "post-board shot list draft" (there is zero evidence that the Fleischers or anyone else used storyboards in the 1920s). The script submitted by Bob Jaques for the Superman cartoon Secret Agent is also a draft, Worth says: "I prepared many similar drafts myself over the years." But it looks nothing like any "golden age" draft I've ever seen, and the relevance of Worth's TV experience to assessing the function of documents from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s is not at all obvious.

What makes such foolishness annoying, as I've said, is its political motivation, the transparent effort to elevate Kricfalusi through a distortion of Hollywood animation's history. Worth is now whining about the "abuse" he has suffered, but he is the one guilty of abuse: of the history of which he claims to be a custodian, and of the credulous fans who have taken his statements at face value.

A Last Word from Brad Bird...

And to end this prolonged discussion on a more upbeat note, here, via Animated News, this quote from Brad Bird in The Hollywood Reporter, about writing for animation:

I don't think it is in any significant way different to write a screenplay for an animated film than a live-action one. What's different is that I know what animators can do and I try to write scenes that I myself would want to animate. I used to be an animator and know what it is like to be assigned these deathly scenes where you have to inject a lot of shtick to make them interesting to watch. What makes (an animation screenplay) work is having a heightened sensibility that is a little bit caricatured. Many people view that as a negative because caricature is meant to suggest over-the-top. But I view the word caricature in a much more positive sense. Good caricature simplifies things down to the essence.

January 10, 2008:

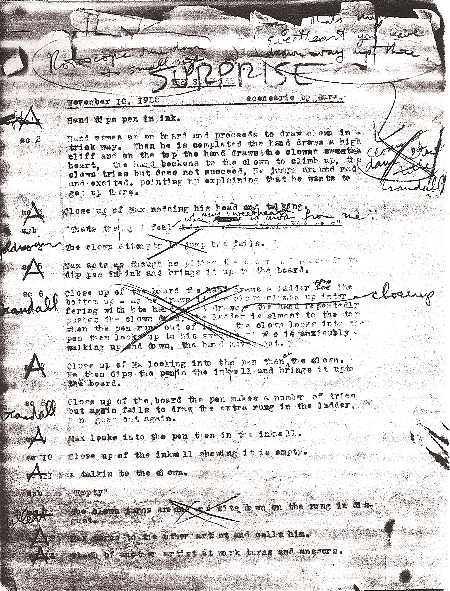

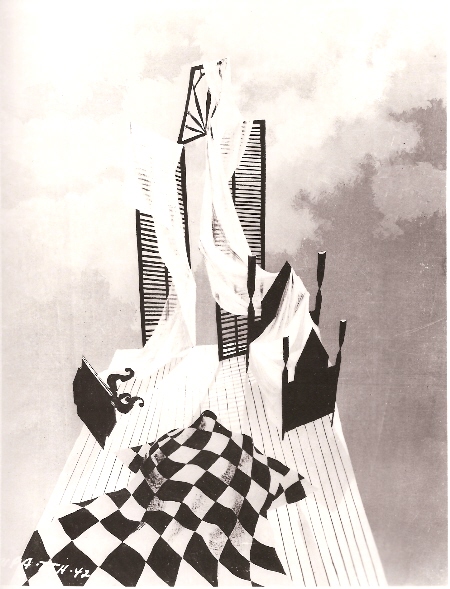

Above is a representative page from a 26-page "treatment" for Cinderella, written by three Disney story men (Ted Sears, Homer Brightman, and Harry Reeves) and dated March 26, 1947. I own this mimeographed "original," but I have many other such documents in my files as photocopies, all of them evidencing a willingness to use written words, as well as story sketches, to tell the stories for the Disney cartoons. Continuities, scenarios, scripts, outlines—they were plentiful at the Disney studio in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, and they turned up at other studios, too. For example, here's the first page of a 1922 "scenario" by Dave Fleischer for Surprise, an Out of the Inkwell cartoon. (My apologies for the murky reproduction; this scan is from a photocopy of the actual scenario, which is part of the Burt Gillett papers at the Walt Disney Archives. The original is a carbon copy, with annotations in pencil and red and blue crayon. Click on either page for a larger version.)

It's tempting to pile up more such examples, but that would be pointless, because Stephen Worth, who initiated the online debate over whether such scripts even existed, has been remarkably ingenious at concocting bizarre explanations for why such documents can't be what they clearly are. He needs to go to work for Fox News, or better yet, the Creation Museum. (The debate, which originated at Cartoon Brew, has continued at Thad Komorowski's Animation I.D. blog, where Bob Jaques has posted a page from another of those nonexistent scripts.)

Worth's explanations reflect his ignorance of how flexible and open and constantly changing the work was at the Disney studio in the "golden age," when you didn't have to choose between scripts and storyboards, but could use both. Worth's explanations also reflect his work experience in the much more harsh and rigid environment of TV animation, where the line between the scripted and the storyboarded is much starker than it was in the old Hollywood studios, and where cartoonists' resentment of what they see as overbearing scriptwriters is much higher. (See the January 8 post by Jaime Weinman for an excellent discussion of the causes and consequences of this situation.)

The current controversy is not really about the use of scripts in the "golden age," but is instead about such TV cartoons, John Kricfalusi's TV cartoons in particular.

Worth, a former Kricfalusi employee, beats the drum for his old boss constantly on his Web site, as in the post that ignited the controversy, the one in which he claimed that cartoon scripts were unknown before 1960. Kricfalusi has been the most visible and vocal of the many animated filmmakers who are resentful of scriptwriters; he complains bitterly that writers have no business working on cartoons, and he insists that cartoons should be in the hands of cartoonists alone. What Worth is saying, against all the evidence, is that that's the way things actually were done in the "golden age," and that's why the cartoons were so good. Ergo, if someone would only give Kricfalusi a pot full of money to make cartoons his way—that is, the way cartoons were made in the good old days—he'd make cartoons just as good as the classics.

The award Kricfalusi will receive February 8 from ASIFA-Hollywood, the organization that Worth controls—an award given until now almost exclusively to veterans of the "golden age"—will undoubtedly be held up as further proof that John K., who has been virtually unemployable for the last few years, belongs in the company of the immortals. In other words, Worth's whoppers are just part of a cynical marketing campaign.

So, should we care if Worth trashes animation's history while he tries to help his hero work his way into a gullible mark's fat bank account? A lot of people would say no. After all, what might be called the "Kricfalusi disease" has already infected most of the Hollywood animation industry. There have been lots of poor imitations of Kricfalusi's Ren and Stimpy, shows that have, as Jaime Weinman says, excluded "certain kinds of jokes and ideas as not 'cartoony' enough. Which might be how a lot of the R&S clones wound up with such weak dialogue, storytelling and characterization."

As for Stephen Worth himself, one friend wrote recently: "Occasionally there are absolute gems on [Worth's] site, but [he has] no sense of what is valuable." That's correct. A great many people will forgive all of Worth's transgressions, though, for the sake of the occasional gem. I think that's a mistake, but Hollywood animation has been so steadily degraded over the last half century that probably one more step down won't make a lot of difference.

I've written elsewhere on the site about the Hanna-Barbera studio's role in that degradation, and Mark Mayerson published a thoughtful critique of H-B on the same day I posted a Hanna-Barbera Feedback page. Here's some of what Mark wrote:

There is no question that TV budgets and schedules were and are brutal for the creation of animation. Hanna-Barbera did nothing to fight this. That is their single biggest failing. Rather than attempt to reform or beat a system that was clearly stacked against the production of good work, Hanna-Barbera embraced that system and milked it for their own personal gain. They expanded the number of shows they produced and with each expansion, the quality of the product suffered. They opened studios overseas in order to take advantage of cheaper labour. The savings went into their pockets, not onto the screen. After their initial decade, when they had the opportunity to work in prime time or in features where budgets were better, the projects were only marginally better than the low-budget work they turned out for Saturday mornings. The thinking and procedures behind their Saturday morning shows infected the entire company. In their hands, the art of animation (and here I'm talking about the entire process from writing to post-production), was degraded and debased without apology.

Amen. John Kricfalusi is—why do I feel the urge to add "of course"?—a warm admirer of the early H-B cartoons.

January 9, 2008:

A Real Golden Age Script

It's probably hoping for too much, but perhaps this item will finally put a stopper in the silly controversy over whether there were real scripts for Hollywood cartoons before 1960, as I've said there were. A visitor to Thad Komorowski's Animation I.D. blog has in effect challenged me to put up or shut up. Here's what he said:

In his writings, Barrier offers no visual evidence of these scripts, only says that he's seen them. This is a controversy that needs some visual evidence. I'd personally love to see an example of a script from a Golden Age so we can put to rest this controversy of "no one ever" wrote a cartoon at that time.

For "visual evidence," and a script from the Golden Age, click here to go to my Capsules page for the 1935 Disney cartoon Who Killed Cock Robin? There are links on that page—and have been, since March 2007—to all twenty-one pages of Bill Cottrell's script/continuity, as well as the preliminary outline and a draft showing who animated what.

Stephen Worth, who triggered this controversy, has now claimed in a comment on Thad's blog that this script was prepared after the film was made—a claim totally inconsistent with the dates on the documents involved, with Bill Cottrell's statements to me about how he worked, and with the script itself, which differs from the film in significant ways. This is vintage Worth. Knock down one of his ignorant statements and he comes back with more, until finally people who actually care about getting the facts right, and not just about self-promotion, walk away in disgust. I've walked away before; but not this time.

Talkin' H-B

Talkin' H-B

I've added a Feedback page about the Hanna-Barbera cartoons and The Hanna-Barbera Treasury, the new picture book that I reviewed recently. (That's Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera at the right, in a photo from around 1967.) Putting up this new page has given me the chance to think out loud, in response to a couple of messages I've posted there, about just how much we owe Bill and Joe for "saving" the animation industry back in 1957.

If you're at all interested in Hanna and Barbera, their MGM cartoons especially, you'll want to read this post at Thad Komorowski's Animation I.D. blog.

Thad mentions how much Hanna and Barbera borrowed from others, including Disney and their predecessors at MGM, Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising. The borrowing really was extensive, to the point that a model sheet for H&B's Jerry and the Goldfish (1951) is exactly the same as a model sheet for Ising's The Little Goldfish (1939), despite the sharp differences in tone and content between the rowdy H&B cartoons and Ising's much gentler comedies.

January 8, 2008:

Solid Brass, Cont'd

Yesterday's item, about Stephen Worth's bogus claim that scripts for Hollywood cartoons did not exist before 1960, prompted Amid Amidi of Cartoon Brew to inaugurate the discussion that you can read by clicking on this link. Predictably, that online conversation turned very quickly toward debate over the virtues and vices of different ways of writing cartoon stories. That's a debate worth having, but my point here has simply been that scripts, in various forms, were a normal part of the process at many studios long before 1960. My charge against Stephen Worth, in this case as in others, is that (1) he doesn't know what he's talking about, and (2) when his errors are challenged he responds with a smokescreen of falsehoods. Such blatant disregard of fact is a strange posture for someone who presents himself as a custodian of animation's history.

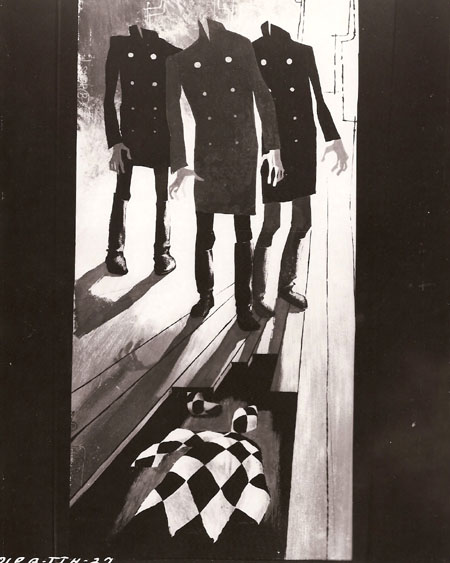

Thanks to the holiday crush, I didn't take proper note of Michael Sporn's two-part posting, fully illustrated with frame grabs, on UPA's 1953 cartoon The Tell-tale Heart. (The illustrations above and below are from publicity stills.) Michael's post was prompted by John Kricfalusi's harsh criticism of the film ("a total boring slow eyesore"), and by Tee Bosustow's remark, in a message published here, about "the bad animation" in the cartoon. Michael's opinion is far more favorable: "It's odd how I feel as though I have to defend this movie. I think it's a brilliant film."

I have Tell-tale Heart on a Columbia videotape from the '80s that also includes just about every other UPA cartoon you really ought to see (Gerald McBoing Boing, Rooty Toot Toot, etc.), and I've watched that film many times, on tape, at the Library of Congress, and at the AFI Theater in Washington. I saw it for the first time in 1973, at a Mark Kausler screening the evening before I interviewed Steve Bosustow. As I told Steve then, Tell-tale Heart feels rushed to me, especially at the end, when the madman's confession is upon us so quickly. If this had been a two-reel film, with more relaxed and expansive storytelling, it would not so often verge on the grim and claustrophobic. And if we could see it in 3-D, as its makers intended, so much the better; this is one cartoon, with its heavily graphic emphasis, that should really shine in 3-D.

I don't have a problem with the animation. It may seem stiff and elementary, but that's fine in a film whose focus is elsewhere. I don't doubt that Pat Matthews gave Ted Parmelee, the director, and Paul Julian, the designer, what they wanted. In Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, I summarized Julian's design as "a joyless pastiche of artistic styles ranging from surrealism to German expressionism," but that may be a little harsh. The different styles are deployed ingeniously, and, as I've suggested, Julian's tableaus would probably be more appealing in a film that gave them more time on the screen. Tell-tale Heart is a cartoon that would have benefited from being "opened up" in more than one way.

January 7, 2008:

Solid Brass

In a December 30 post, I pointed out that animation's equivalent of Professor Irwin Corey, the World's Greatest Authority, was peddling the nonsensical notion that no scripts for Hollywood animated cartoons existed before 1960. Ross Irving wrote to the World's Greatest Authority recently, challenging his grotesque falsehoods and saying, correctly, that "If you went to the Disney Archives and jokingly asked the directors of that archive for a script, they would give you quite a few pages from Snow White and other features."

The World's Greatest Authority replied on his site as follows: "The only scripts used in the golden age at any studio were transcriptions off the storyboards for the convenience of voice actors or film editors. Snow White and the other Disney features were written in drawings, not in script form." His evidence? A clip of Walt Disney from a 1950s TV show, in which Walt offered a dumbed-down explanation of how his cartoons were made.

Presumably that old TV show counts for a lot more than all the archival scripts and continuities, at the Disney studio and elsewhere, that were unmistakably written very early in work on the films involved. When Walt dictated a detailed "skeleton continuity" for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in December 1934, was he simply reading back what was already on a complete storyboard? And was Bill Cottrell lying when he told me that he didn't draw at all but wrote his many stories for the Disney cartoons as scripts that people like Joe Grant and Bob Kuwahara translated into drawings?

Actually, I suppose Cottrell must have been lying, since we have the word of the World's Greatest Authority that "a good story man in the golden age didn't have to be a terrific draftsman, but he had to be able to put his ideas across in sketches." I mean, if you can't trust the World's Greatest Authority, who can you trust?

The World's Greatest Authority ended his response to Ross Irving by saying: "At some point I'll do a post outlining the exact process from the very first gag session through the finished film. That might make it clearer for you." Gosh. I can't wait.

January 6, 2008:

The Hanna-Barbera Treasury

You can read my review of the new picture book devoted to the Hanna-Barbera TV cartoons of the 1950s and '60s, with text by Jerry Beck, by clicking here.

Too Much Conversation

Colin Giles has responded to my January 3 post on voice performances with a post on his blog about the deadening prevalance of talk in today's animation, and the virtues of silence. To read it, click on this link.

Colin also remarks, in a message to me: "The topic of animation voice recording brings up the point of having a good director who will keep in mind not only the needs and requirements of the actor but simultaneously those of the animator. Too many times it's obvious the record button is hit and the actor let loose and the animator left to stitch it together."

Anyone who has suffered through a recent feature with a voice performance by Robin Williams can appreciate the justice of what Colin says.

January 3, 2008:

Walt and the Voices of Alice

[A January 6 update: Michael L. Jones has provided links to more Web pictures of George Chandler, and they have made me more doubtful of the identification of the man at the NBC microphone as Chandler. He looks too young, for one thing. I would guess he was an announcer who happened to resemble Chandler, but the question is still open.]

I've heard from several people about the identity of the man in the December 28 photo of Walt Disney and Margaret O'Brien. J. B. Kaufman and Kliph Nesteroff think think it's George Chandler, a bit player who was in hundreds of movies in the 1930s and '40s, usually uncredited. John Benson is more doubtful, but he also leans toward the Chandler identification. Photos of Chandler are not plentiful on the Web—even though he was for a time president of the Screen Actors Guild—and I can't claim to know his screen work well enough to draw any firm conclusions. But for now, let's say it's Chandler. But what was he doing in front of an NBC microphone with Walt and Margaret O'Brien?

That's not at all clear, but we can be virtually certain that this photo was taken very early in June 1949, as part of the publicity effort surrounding the choice of O'Brien as the voice of the title character in Disney's animated feature version of Alice in Wonderland. That choice was announced in the Los Angeles Times of June 3—but three days later, O'Brien was out of the film, thanks to the turmoil surrounding the collapse of her mother's short-lived marriage to Don Sylvio, an orchestra leader. Contracts had been drawn up but not yet signed, O'Brien's agent told the Times.

O'Brien herself, in a 1998 interview with Allen Ellenberger, said, "My mother had a big fight with Walt Disney. What it was all about I don't know. I think it was over money. And he was going to sue us—it was a big deal. Somehow he didn't, and at that point neither one of us wanted to do it." That seems unlikely, given how quickly the O'Brien deal evaporated—and how quickly Walt signed a replacement—but perhaps that was what Margaret's mother wanted her to believe. MGM had just dropped O'Brien, a contract player for eight years, so there were multiple reasons for stress in the O'Brien household..

As for that replacement: On June 8, 1949, just two days after O'Brien's withdrawal, Walt announced that Kathryn Beaumont, then a few days short of eleven years old and already a veteran of several MGM live-action features, would be Alice's voice. The photo above, showing Kathryn "signing" with Disney (which as a minor she couldn't legally do, of course), accompanied the Los Angeles Times' story about Walt's choice. By June 22, as "call sheets" in the Disney Archives show, live-action filming of Kathryn, as reference material for the animators, had begun; the first such filming was for the caterpillar and tea-party sequences.

Margaret and Kathryn had both appeared in O'Brien's last MGM film, The Secret Garden, but Kathryn's most substantial role was in a surprisingly enjoyable Esther Williams musical, On an Island With You (1948), which turns up occasionally on Turner Classic Movies and is available on DVD. She was a charming little actress—and, as it turned out, an excellent choice for the voice of Alice.

More on Satoshi Kon and Bob Clampett

Daniel Thomas MacInnes has written to alert me to his impressive blog on Japanese animation, Conversations on Ghibli, and particularly to his stimulating review of Paprika, the Satoshi Kon-directed feature that I reviewed favorably last August. My review led to the responses gathered on my Feedback page devoted to Kon. I've just gotten from Netflix the DVD of Tokyo Godfathers, the Kon film that preceded Paprika, and I hope to have some comments on it soon.

And on the subject of feedback, I've added some from Keith Folk to the Bob Clampett Feedback page.

Character First, Voice Later?

Speaking of Japanese animation, Hayao Mizyazaki's example inspired this contrarian view about voice performances in Ed Hooks's newsletter:

Another big problem is the fact that, in the U.S., we record voice performances first and then make the animation second. Miyazaki still makes animation first and, afterward, loops in the actors' voices. Ever since "Lady and the Tramp," we have done things the other way around in the U.S.—voices first, animation second. [I'm guessing that Ed is not speaking of L&T specifically—pre-recording was the norm long before that film was made—but is simply saying that pre-recording has been the norm for a long time.] I don't have a problem with the voices coming first, but I can see how an animator might feel that his main job is to make his animation fit the voice. You hear the words in the headphones, and you try to make the character on-screen look like he is actually saying the already-recorded dialogue. In truth, acting has almost nothing to do with words. Acting is doing. It is all about action. No matter how expert an animator may be at matching animation to pre-recorded words, it is not enough unless the character on screen is actually playing an action. Once again: "Action, in pursuit of an objective (which should be provable), while overcoming an obstacle."

Reading Ed's comments, I was reminded of what Dick Lundy told me many years ago (as quoted on page 118 of Hollywood Cartoons) when we were talking about the mid-1930s Disney shorts: "Personality more or less came when they opened upon the dialogue. It was the dialogue that had the personality that you tried to portray." In other words, Dick—like many other animators, too, I think—saw pre-recorded dialogue not as a constraint but as an aid to bringing a character to life. If post-recording has now become attractive to some, perhaps that's because today's cartoons tend to be so dialogue-heavy, and their dialogue is so often driven by the desire to thrust forward not the character itself, but the star speaking the lines.

Writers and Drawers

Wayne Bryan wrote in response to my December 30 item about the silly claim that cartoon scripts didn't exist before 1960: