"What's New" Archives: February 2008

February 29, 2008:

February 27, 2008:

Tex Avery: 100 Years and a Day

February 26, 2008:

February 23, 2008:

A 1932 Interview with Elias and Flora Disney

February 22, 2008:

February 19, 2008:

February 18, 2008:

February 17, 2008:

February 15, 2008:

February 13, 2008:

February 12, 2008:

February 8, 2008:

February 7, 2008:

February 6, 2008:

February 4, 2008:

February 29, 2008:

Where Walt Was: November 1942

[A March 1 update: Ron Bevilacqua has shared another clipping of this photo, this one earlier than the others, from the Philadelphia Inquirer of November 30, 1942. So it seems all but certain that the photo in the clippings, and the photo I reproduced on February 26, were taken sometime in November. I've changed the head and the tag for this item accordingly.]

Thanks to John Donaldson for his quick solution to my February 26 item about a photo showing the actress Joan Bennett presenting a medal of some kind to Walt Disney.

As the caption above shows, the award was for Bambi, from what the caption identifies as the "American Humane society." That would have been the American Humane Association (the Humane Society of the United States wasn't founded until 1954). American Humane is best known as the organization that has since 1940 monitored the treatment of animals during film and television production.

The Disney-Bennett photo ran in a number of newspapers early in December 1942 in exactly the same format; it was probably distributed as a matrix that could be converted into a metal plate. It appeared in the Massillon (Ohio) Evening Independent on December 2, and in the Reno Nevada State Journal on December 5. I'd guess that the photo was taken a few weeks earlier, sometime in November.

February 27, 2008:

Tex Avery: 100 Years and a Day

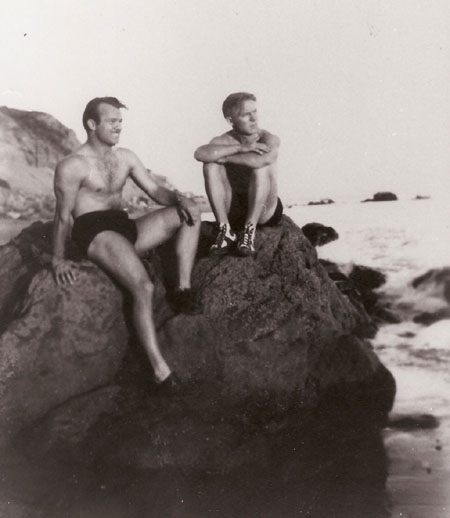

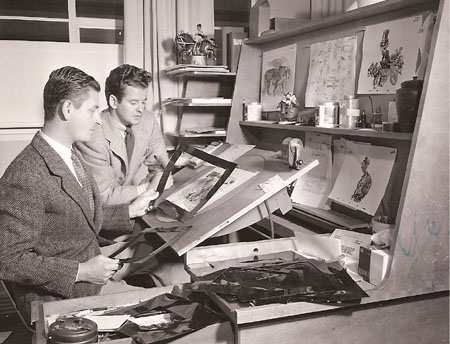

Frederick Bean "Tex" Avery was born a hundred years ago yesterday, an anniversary marked on many other blogs, among them Thad Komorowski's, David Germain's, and Jaime Weinman's (where you'll find links to other Avery-related posts). Here, arriving a little late to avoid the crush, are a couple of early-'30s photos of the very young Avery, a less familiar figure than the rotund director of the Schlesinger and MGM days. The top photo shows a surprisingly slim Tex, all of 22 in 1930, at the shore with the animator Jim Pabian, the bottom one shows him at the Universal studio a few years later with the animator Jack Dunham. Jim Pabian lent me the top photo, Dick Hall the bottom one.

February 26, 2008:

Where's Walt, No. 5

To judge from a note on the back of this photo of Walt Disney and the actress Joan Bennett, it was published in Modern Screen for April 1943, but I haven't yet tracked down a copy of that issue (even the Motion Picture Academy's Margaret Herrick Library doesn't have it), and at this point I have no idea of what the occasion was or what the medal represented. If anyone does know, please share.

And Speaking of Walt...

David Lesjak, whose two blogs—Toons at War and Vintage Disney Collectibles—are consistently rewarding sources of Disney historical information, has published on the latter site a highly detailed account of the 1932 ceremony at which Walt received his first two Academy Awards, for Flowers and Trees and Mickey Mouse. I hadn't realized until I read David's piece that the ceremony, held at the Ambassador Hotel, occurred four years to the day after Steamboat Willie's premiere. Walt had covered quite a bit of ground in those four years.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Andrew Osmond advises that a 1995 British documentary about Walt's "secret life" is now available on YouTube in six parts, starting with the one at this link. " It's a hatchet-job," Andrew writes, "giving the likes of Marc Eliot and Richard Schickel their head, but you might find some of the employee interviews interesting. It was broadcast on Britain's Channel 4 in 1995 (which was back when the British media was taking [Eliot's] Hollywood's Dark Prince as The True Story)."

I've watched only the first three parts, which give undue prominence to Bill Melendez, Schickel, and the loathsome Eliot, each of whom tells some whoppers. The few people shown who are sympathetic to Walt, like his biographer Bob Thomas and the animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, must have felt they'd been had when they saw the finished film.

...And of The Animated Man

I wrote a few weeks ago about the savage denunciation of my Disney biography, The Animated Man, that someone calling herself Patricia Block posted as a review on the amazon.com and bn.com pages devoted to the book. I was particularly disturbed by her attribution to me of what appeared to be a fabricated quotation. Yesterday, I revisited her amazon review, to see if by chance she had responded to the criticisms posted by me and some other readers. She hadn't—no surprise—but A. Peterson, a visitor to this site who has not yet bought or read The Animated Man, had posted this revealing comment on February 17:

It should be noted that the author of this excessively harsh review, "Patricia," has written NO other reviews, nor has "she" returned comment to any of the responses that have followed, not even that of the book's author. Best case scenario: this review was attached to the wrong book, (repeatedly; see below) and the reviewer is too embarrased to respond—an innocent mistake. Worst case scenario: this review was purposely written to negatively damage the reputation of the book.

Sadly, I must say I believe the latter to be true. To gain a little perspective, I did a simple Google search on the exact quote, "everything Walt touched was worse for the attention he gave it." Initially, Google displayed one result, but had the italicized blurb beneath stating that there were ommited results. After clicking the link to include the omitted results, I was presented with 44 results. 44!!! Each of them was a book review, on various sites that allow users to review particular books. This exact review has been published on the internet in 44 places, yet it is the ONLY reference to the alleged "direct quote" anywhere on the web.

Wow! I had no idea there were 44 places on the Web where you could review a book! Obviously, The Animated Man is the target of a vendetta of some kind. Maybe "Patricia" is Neal Gabler's or Marc Eliot's childhood buddy/college girlfriend/maiden aunt? I have no idea. It's kind of flattering to be the target of such intense fury, but as the man said when he was tarred and feathered and ridden out of town on a rail, if it weren't for the honor of the thing, I'd just as soon walk.

February 23, 2008:

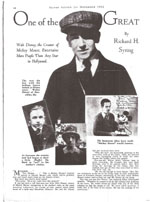

A 1932 Interview with Elias and Flora Disney

When I was writing The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, I read dozens of articles about Walt from the 1930s, but it was not until last year, after the book was published, that I got around to this relatively obscure one, "One of the Great Geniuses," by Richard H. Syring, from Silver Screen for November 1932. It's based on what the author presents as an interview with Walt's parents, Elias and Flora Disney, at their home in Portland, Oregon.

My first thought when I read it was, can this be for real? The cozy tone and the too-pat quotations from the elder Disneys induce skepticism, but the article is mostly accurate (confusion about the Alice Comedies' success aside), and then there are those photos, which must have originated with Walt's family. So, the odds seem pretty good that an interview of some kind actually took place—even if what Elias and Flora said bore limited resemblance to what was published—and that this article is one of the earliest, if not the earliest, printed instance of some of the most familiar stories from Walt's childhood.

To read the article (from a photocopy), click on one of the images above, from which you can navigate to any of the article's three pages.

February 22, 2008:

Hollywood Cartoons on Sale

[A March 5 update: If you didn't buy Hollywood Cartoons on sale, I'm afraid it's too late.Amazon.com is again selling the book for its full list price, currently $27.95.]

[A March 5 update: If you didn't buy Hollywood Cartoons on sale, I'm afraid it's too late.Amazon.com is again selling the book for its full list price, currently $27.95.]

What? You don't own a copy of my book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age? You say you've heard bad things about it? That I didn't praise Bob Clampett effusively enough? That I was mean to Joe Grant? You say you don't want to enrich an author who would do such naughty things? Well, now's your chance to pick up the book without putting much coin, if any, into my greasy pocket.

Amazon.com is offering the trade paperback—the second printing, with every error that I could find corrected—for all of $5.62, or 80 percent off the list price of $27.95. I don't know what's going on, if the book is being remaindered or if the publisher is simply reducing its stock to a more manageable level. Probably the latter—Hollywood Cartoons is still listed at full price on Oxford University Press' Web site—but who knows. I've bought four copies for myself, and you may want to buy at least one, even if you have the hardcover, just for the sake of having an error-free (I hope) copy.

The Last Roundup

I don't want to extend the ongoing conversation about Bob Clampett's Buckaroo Bugs to absurd lengths—we're not talking about Citizen Kane here, as one of my correspondents reminds me—but I can't call a halt without letting a last few visitors have their say. Like this, from Gordon Kent:

I don't want to extend the ongoing conversation about Bob Clampett's Buckaroo Bugs to absurd lengths—we're not talking about Citizen Kane here, as one of my correspondents reminds me—but I can't call a halt without letting a last few visitors have their say. Like this, from Gordon Kent:

I just read your latest back and forth with Eddie Fitzgerald regarding individual scenes and details versus the entire film and that's exactly my feeling on the matter. Yes, fans of films like Robin Hood—particularly animation professionals—can point to scenes that that may last a few seconds that they think are marvels of the art. Or they can freeze a frame of film and discuss how wonderful a drawing it is. But these films aren't meant to be viewed as individual frames or even scenes.

The point of a film (animated or otherwise) isn't the mechanical precision of an individual drawing or scene, but the overall sense that you get when the film is over. The entertainment comes from the wonder of the characters performing—acting out a story—displaying our foibles to us—growing or not growing as characters. The audience may laugh in hysterics at a scene or a moment here and there, but they can still feel let down at the end because the film as a whole didn't live up to its promise.

Maybe a civilian audience member can't appreciate the "genius" of a moment or a drawing the way a professional can, but they can appreciate whether or not the film entertained them, and they aren't going to leave the theater singing the praises of an individual drawing. Neither are they going to bother buying the DVD so they can single-frame the thing and gape in wonder at the individual drawings. Which isn't to say that a student of animation or film shouldn't marvel and appreciate an individual drawing or sequence of drawings—just don't get lost in the minutiae.What you said about Bugs' personality is (in my estimation) correct. He doesn't work when he's mean or a bully—he works best when he reacts to bullies. He can't make the first strike! This is pretty much the case with most protagonists. Think of Tex Avery's Bad Luck Blackie: it's okay that all those horrible things happen to the dog because for the first thirty seconds or so of the cartoon we watch him torture the little kitten. We feel that he deserves anything that happens to him—the worse, the better and funnier. If the dog had been innocently minding his own business, he wouldn't deserve any of it, and it wouldn't be funny.

I also might add that Bad Luck Blackie's gags escalate. They start with a flower pot and end with a steamship (among other things) landing on the dog's head. My problem (but clearly not everyone's) with some of Clampett's cartoons (and John Kricfalusi's as well) is that they start out on the ceiling and stay there the whole time. They don't escalate because there's really no place to go but down.

From Lucas Libanio, in Brazil:

From Lucas Libanio, in Brazil:

I do not think we need to dislike this cartoon (and others with Bugs that Clampett did) to agree with you or at least understand your points. Myself, I like the odd gags, the animation (especially Scribner's), and the design of Red Hot Ryder. My problem with the cartoon itself is really Bugs's characterization. I like aggressive characters (like Woody Woodpecker and Screwy Squirrel), and I like aggressiviness in Bugs when it is well managed (Rebel Rabbit and Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid come to mind), but here we have a kind of cheap characterization, almost a generic hecker's attitude, many steps back from the characterization Tex Avery gave to him in A Wild Hare.

And finally, to come full circle, from Ricardo Cantoral, whose message ignited the discussion of Buckaroo Bugs:

I seem to have sparked another healthy debate between you and a member of the Spumco crew, dear old Uncle Eddie. I enjoy them because I usually learn so much. Anyway, I want to address some more of your criticisms of Bob Clampett's Bugs. I don't think Bugs is sadistic, as you make him out to be. Take for example that teeth-pulling gag from Buckaroo Bugs, I never found it sadistic at all. Remember that Bugs used the magnet on Ryder's belt then made his way up. The teeth pulling was just an extra part of a larger gag, stealing his possessions via a magnet. That really isn't going far at all. I also didn't find that last gag in Hare Ribbin' out of Bug's character either. Bugs shooting him in the mouth was essentially the old "let me have it!" routine taken to the extreme. There was a hilarious initial setup with the dog's lament and his pleas to die. Also remember the dog got up to say one last funny line. I hope I don't offend you when I say this, but I think you are only focusing on the bits that you don't like and you're disregarding the appeal of the scenes in question. Please have an open mind when you watch these cartoons, there is a lot to love!

I can certainly agree with Ricardo's closing sentiment as it applies to Bob Clampett's Warner cartoons in general, even if I still have trouble applying it to Buckaroo Bugs and Hare Ribbin'.

And just a little off topic...

...But not really, since a large part of the discussion of Buckaroo Bugs has been about whether it's a good idea to concentrate our attention on individual pieces of animation, as opposed to the film as a whole. As Gordon Kent wrote, an emphasis on details can sometimes backfire:

One of the reasons that Saturday-morning cartoons got to be as bad as they did is that executives would look at the film, freeze frames, and call retakes because the characters didn't "look like the model sheet." These were inbetweens! Or sometimes extremes. Not only didn't it matter that they were "off model" sometimes they were supposed to be off model! It aided the sense of movement and speed. This occurs even in features where people have lost the art of "smearing." Suddenly every drawing must be on model, and that causes everything to move more stilted or slower. They fail to look at individual frames of live-action films where the actors in movement are seen with a "smear" effect.

February 19, 2008:

My Little Buckaroo

Eddie Fitzgerald didn't much like what I wrote February 18 about his post praising Bob Clampett's 1944 cartoon Buckaroo Bugs:

I don't believe everything Clampett did was wonderful. I wouldn't say that about any artist in any field. You're reading too much into the simple fact that I like a cartoon that you don't. What makes you think that my defense of Clampett was excessive? Yourevidence against Buckaroo Bugs was that the magnet gag was sadistic and too explicit, and the open mouth was gross. That's it. Unless I missed something, that's all there was. You criticized a small part of the film, then pronounced the entire film defective. If you had said that in a light-hearted way, speaking as a fan, it wouldn't bother me, but no, you spoke with the authority of Zeus, handing out punishments right and left to all who disagree. You described me as a fanatic just because I dared to have a different opinion of a single cartoon.What's the sense in that?

Reading Eddie's post about Buckaroo Bugs put me in mind of Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, oddly enough, and their exquisite analyses of the animation for such Disney features of the '70s as Robin Hood and The Rescuers. Reading those analyses in Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life, I often wanted to yell, "Wait a minute, you guys! It's Robin Hood we're talking about! If the animation is so damned wonderful, why does the movie stink on ice?" (I once tried asking Frank and Ollie a question of that sort—worded much more politely, of course—when I was interviewing them. They ignored it.)

The point being, it's as easy to praise a film lavishly on the basis of what Eddie calls some "small part" of it as to condemn it. What I see in a great many posts praising Clampett's cartoons, like Eddie's on Buckaroo Bugs, is a focus on details of direction and animation, at the expense of any serious examination of the films as a whole. In a number of cases, I think, it's much easier to praise a Clampett cartoon on the basis of those details than of the impression left by the entire film.

What makes most of Clampett's Bugs Bunny cartoons unattractive to me—and this is what I tried to address in my earlier posts—is something more important than the occasional unpleasant gag, and more important, too, than any felicitous details. What really matters is Clampett's conception of the character, which is fatally flawed. Bugs in Clampett's hands too often calls to mind a contemptuous, arrogant bully. Sometimes Clampett's Bugs Bunny cartoons go completely off the rails, as with the original ending of that very strange cartoon Hare Ribbin' (see the frame grab).

What makes most of Clampett's Bugs Bunny cartoons unattractive to me—and this is what I tried to address in my earlier posts—is something more important than the occasional unpleasant gag, and more important, too, than any felicitous details. What really matters is Clampett's conception of the character, which is fatally flawed. Bugs in Clampett's hands too often calls to mind a contemptuous, arrogant bully. Sometimes Clampett's Bugs Bunny cartoons go completely off the rails, as with the original ending of that very strange cartoon Hare Ribbin' (see the frame grab).

Clampett's conception of the character changed, after he was away from Bugs for more than a year, and Bugs benefited. I very much like the Bugs of The Big Snooze, Clampett's last Bugs cartoon—a less polished film than the earlier ones, unfortunately—and I wish that that Bugs were present in the earlier cartoons as well.

It seems to be easy, in making all kinds of films as well as in writing about them, to lose oneself in the little things. When I saw Paul Thomas Anderson's highly praised feature There Will Be Blood a few weeks ago, I was impressed by how intelligently staged and acted it was, every shot a marvel of some kind, evoking time and place with remarkable precision. (To read about how skillfully just one scene was directed, go to this post on David Bordwell's site.) I was also, by the end of the film's very long two and a half hours, bored out of my mind. You can suffocate under all those damned beautifully executed details.

February 18, 2008:

Emery Hawkins at Lantz

Thad Komorowski has posted John Canemaker's interview with Emery Hawkins, a greatly admired animator who worked at many studios and was interviewed on few if any other occasions (he politely turned down my request for an interview when I wrote to him in 1978). Thad didn't have any pictures of Hawkins, so here he is, in a couple of group photos from the Lantz studio, one taken in 1944, the other in 1945.

The Lantz animation staff in 1944: top row, from left, Paul Smith, Grim Natwick, Sidney Pillet, Bernard Garbutt; bottom row, Les Kline, James "Shamus" Culhane, Pat Matthews, Dick Lundy, and Emery Hawkins.

The Lantz staff in the spring of 1945: top row, from left, Ben "Bugs" Hardaway (story), James "Shamus" Culhane (director), Emery Hawkins (animator), Milt Schaffer (story), Tony Sgroi (assistant animator), Jack Bailey (breakdown), Les Kline (animator), Bernard Garbutt (animator), Casey Onaitis (assistant animator), Grim Natwick (animator), Sidney Pillet (effects animator), unidentified), Dick Lundy (director), Ed Solomon (assistant animator), Paul Smith (animator), François "Frankie: Smith (assistant animator), unidentified; bottom row, unidentified, unidentified (both were assistant animators), Charlotte Huffine (assistant animator), Pat Matthews (animator), Mabel Lundy (effects assistant and airbrush artist), Ellen Starr (checker).

Dick Lundy lent Milt Gray and me both photos for copying (Paul Smith also lent the 1944 photo, and Mrs. Frankie Smith the 1945 photo). Roger Armstrong, who worked at the Lantz studio briefly during World War II, provided some of the identifications. Needless to say, I'd welcome the names of any of the unidentified persons in the photos.

The First Church of Bob

Eddie Fitzgerald, a nice kid who hangs with a rough crowd, his old mates at John Kricfalusi's Spumco studio, wrote in response to my recent posts about Bob Clampett's 1944 cartoon Buckaroo Bugs:

I liked Buckaroo Bugs a lot more than you did, but what moves me to write is what you said about Red Hot Ryder's open mouth being unappealing. Aaaargh! I love open mouths in cartoons! The idea that we all have a hidden cave in the front of our face, that it's rimmed with porcelain chicklets, and is the home of a giant clam that lives on the bottom, is hilarious! Even funnier is the fact that you have to throw food into the cave at regular intervals, and if it's not masticated by chicklets and licked by the clam, the stomach won't accept it.

Well...if you say so, Eddie.

Eddie has also posted on his blog an extraordinarily detailed analysis of just a small part of Buckaroo Bugs. Eddie's analysis, sincere and intelligent though it is, doesn't begin to address the misgivings I've expressed about Buckaroo Bugs, and it doesn't come close to persuading me that that cartoon isn't one of Clampett's worst misfires.

Eddie has also posted on his blog an extraordinarily detailed analysis of just a small part of Buckaroo Bugs. Eddie's analysis, sincere and intelligent though it is, doesn't begin to address the misgivings I've expressed about Buckaroo Bugs, and it doesn't come close to persuading me that that cartoon isn't one of Clampett's worst misfires.

For the true believers—and I count Eddie among their number—every one of Clampett's Warner cartoons is wonderful, and, more than that, everything about them is wonderful, so there's no way analysis can be separated from affirmation. You gotta believe, and you gotta believe it all. The fear seems to be that acknowledging any lapses on Clampett's part might bring down the whole edifice of his reputation. I live in a part of the country thick with fundamentalists, and so, perhaps inevitably, the phrase "biblical inerrancy" springs to mind.

When Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age first appeared, I heard that some Clampett fans thought the book had been spoiled—rendered unfit for the faithful to read—by one sentence. I don't remember which sentence it was, and I didn't take that complaint seriously anyway, because it was clear to me that if I had somehow been able to remove the offending sentence from the book, another sentence would have been found wanting, and then another, until finally nothing was left—nothing about Clampett, anyway. My real sin was not writing one heretical sentence. It was instead taking Bob seriously enough to suggest that his films sometimes fell short of his own highest standards—and for reasons that made him all the more interesting as an artist, and that illuminated what he had achieved in his best cartoons.

As I wrote here on January 29, hero worship is a widespread disease among animation fans and professionals. Clampett is certainly not the only victim of it. I doubt there's a prominent animation figure, past or present, who doesn't have at least one or two nutcase followers, and sometimes, as with Walt Disney, many more than that. Hero worship isn't exactly unknown in the other arts, either, but it seems especially contagious in Hollywood animation. Perhaps that's a measure less of the worshipers' credulity than of the presentday industry's creative squalor. If I were working on something like Chicken Little or Bee Movie, I'd be yearning for a few heroes to admire, too.

...And Speaking of Clampett

Don't miss Jaime Weinman's excellent post, "Bob vs. Chuck," in which Jaime argues that the rival claims about who "created" the Warner characters must be seen in the context of the animation industry at the time those claims were being made. Such claims became more attractive as the industry itself was faltering, circa 1970, and as people like Clampett and Chuck Jones began to realize that their place in animation's history was going to be determined not by what they did in the future, but by work they had done decades earlier. There's probably truth in that, although I think Jaime understates the importance that directors like Clampett and Hanna and Barbera attached to their theatrical-cartoon credentials even when they were riding high as TV-cartoon producers.

February 17, 2008:

Walt in England, Cont'd

In 1949, when he made Treasure Island, his first all live-action feature, in England, Walt Disney was not yet the instantly recognizable celebrity that television would make him five years later. But his name was certainly well known, and enough people knew what he looked like that he found himself in the midst of a crowd of autograph seekers in London. To read an earlier post about Walt's first few filmmaking journeys to England, click on this link.

February 15, 2008:

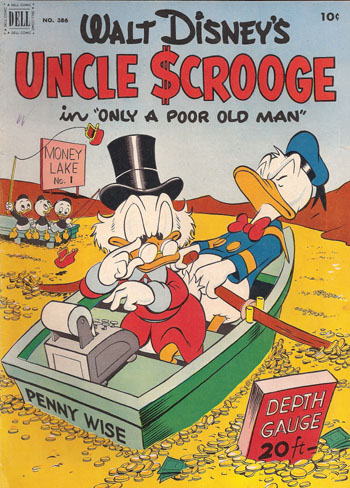

A Barks Masterpiece

Every Saturday, the Wall Street Journal publishes on its last page an article about a "Masterpiece," some painting or book or musical composition or building of enduring merit. I've read a lot of those articles—I subscribe to the Journal in its paper and Web versions—and it occurred to me that a number of Carl Barks's stories richly deserve the "Masterpiece" label. With the encouragement of a friend who writes occasionally for the Journal, I submitted a "Masterpiece" article about "Only a Poor Old Man," the story that filled the first issue of Uncle Scrooge in 1952.

Every Saturday, the Wall Street Journal publishes on its last page an article about a "Masterpiece," some painting or book or musical composition or building of enduring merit. I've read a lot of those articles—I subscribe to the Journal in its paper and Web versions—and it occurred to me that a number of Carl Barks's stories richly deserve the "Masterpiece" label. With the encouragement of a friend who writes occasionally for the Journal, I submitted a "Masterpiece" article about "Only a Poor Old Man," the story that filled the first issue of Uncle Scrooge in 1952.

My piece came bouncing back so quickly that I'm sure the editor who rejected it did no more than glance at it. I realized, after looking over the list of "Masterpieces" published in the last couple of years, that what I might call a New Criterion sort of elitism is at work in the choice of subjects for that feature, and that anything coming out of popular culture (a few pop-music icons aside) has almost never made an appearance. Barks never stood a chance.

My friend offered to help find another home for the piece, but after years of writing free-lance articles (and years of editing them for the magazine I used to work for), I can't work up any enthusiasm for tugging on editors' sleeves. Instead, if you wish, you can read "The World's Richest Duck" here. If this piece reads a little differently from some of my other essays and reviews, remember that it was written for a different audience than the one that usually visits this site.

Although "The World's Richest Duck" is a stand-alone piece, it's also a preview of sorts of some of the ideas I'm developing for my next book, a survey of mid-century comic books (the Dell titles especially) called Funnybooks. I expect to test out some other ideas for that book in other postings in the months ahead.

Speaking of Barks...

Thanks to E. Horst of Munich, Germany, I've added ten more corrections to the page devoted to my page called Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book: Corrections, Clarifications, and Amplifications.

...And of Comic Books

Dana Gabbard and I have been exchanging emails about Dell Comics' curious emphasis in the early 1950s on subscriptions, as opposed to newsstand sales. As I said recently, it was hard for me to see how the economics of subscriptions worked to Dell's advantage, even given how much more that a dollar (the cost of a year's subscription to Dell's monthly titles) bought fifty-odd years ago than it buys now.

As Dana has pointed out to me, Dell's emphasis on subscriptions extended to taking out full-page ads in the Saturday Evening Post in late 1952 and early 1953. There was a public-relations aspect to such ads—Dell certainly wanted to distinguish itself from the crime-and-horror publishers that were under increasing attack at the time—but that can't be the explanation for the emphasis on subscriptions as well as the Dell comic books' wholesomeness. I seem to recall, from my days of haunting the local dime stores each week, seeing unopened packages of new Dell comics (oh, the agony!) marked as second-class postal matter. So, was the appeal for subscriptions, through ads in the comic books and elsewhere, necessary to meet postal requirements and secure lower shipping costs? And what accounted for the differing treatment of subscriptions in different Dell titles? (Subscription ads ran in all the monthlies, I recall, but rarely if ever in the titles published less frequently, even when they had second-class mailing permits.) Did Dell begin a subscription push, as Dana suggests, out of fear that newsstands might be less and less hospitable to comic books of all kinds?

I'd like to think that at least some of the corporate records of Dell and Whitman/Western Publishing have wound up in some library or other institution, but I've heard nothing to suggest that that's the case. Does anyone know anything different?

Short Shots

° A program made up of the Oscar-nominated shorts, live-action and animated, opens today at 80 theaters, and will play at more later, with DVD release to follow. To read about all the shorts, visit this page on the superlative film site that Kristin Thompson shares with David Bordwell. Among other things, Kristin offers provocative suggestions about why animated shorts, taken as a group, tend to be consistently superior to their live-action counterparts: "There’s not much of a theatrical market for live-action shorts, which mainly get seen at festivals and on TV. They tend to be portfolio films, made by people trying to attract attention and move up to features. Hence they more often come from beginners. Animators who don’t want to work their way up through big studios—and who stand little chance of ever directing a major animated feature—or who simply value their independence may stick with shorts."

° David Gerstein, whose Mickey and the Gang was praised a few days ago on the Hanna-Barbera Feedback page as a happy contrast with the recently published Hanna-Barbera Treasury, has offered some details about what went into the making of his book—and some perhaps surprising praise for the H-B book. You can go directly to his comments by clicking this link.

February 13, 2008:

Jim Bodrero Interviewed

Jim Bodrero was one of the leading lights in Joe Grant's model department at the Disney studio in the late 1930s and early '40s. He was also a strikingly suave and cosmopolitan figure at a studio many of whose artists have always been unsophisticated, to the point of naïvete. (That's Bodrero at the left in the photo above, with his younger colleague John P. Miller.) Milt Gray interviewed Bodrero in January 1977, as part of the research he and I conducted for Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, and you can read the complete transcript of that interview by clicking on this link.

Because I was struggling with a huge backlog of taped interviews, I wasn't able to get the transcript to Bodrero for his review before his death in 1980. His daughter, Lydia Hoy, read the transcript, however, and wrote to tell me how much everyone in her family had enjoyed it: "It was as though we were hearing Dad speak again!"

Milt interviewed Jim Bodrero on a trip down the California coast during which he interviewed close to a dozen veterans of Hollywood animation's "golden age," including Art Davis, Gus Arriola, Ed Benedict, Ralph Wright, and Campbell Grant. He and I had made a similar driving trip the previous fall, starting at Calistoga in the Napa Valley with Ben Sharpsteen and stopping to see Dave Hilberman, Bob Carlson, Lee and Mary Blair, and Howard Swift, before arriving in Los Angeles, where I did much more interviewing. Milt and I picked up a lot of phone numbers and addresses on the fall trip, and there were still so many good interview candidates left in northern California that he volunteered to go back and pick up the people we'd missed.

I did a lot of advance work, through letters and phone calls (my notes from a phone conversation with Jim Bodrero fill a typewritten page, for instance), and I prepared a detailed itinerary for Milt with lots of information about the people he would be seeing. Milt came through with superb interviews with everyone he saw, except for two veteran animators who at the last minute welshed on their commitments to sit for a taping. (One simply didn't want to talk about what had apparently been some unpleasant experiences; the other said he had decided to write his own book, which he never did.)

Milt and I absorbed all the costs of our travel, of course. Once I began transcribing the tapes, I could expect each hour of tape to require three to four hours at the typewriter (no computers in those days). Then I mailed the completed transcripts to the people we'd interviewed, for their review and their corrections, usually with additional questions.

Such facts spring to mind whenever I hear that some whining fanboy has declared that I somehow have an obligation to dump all my research in the lap of a self-proclaimed "archivist," or that the hundreds of interviews Milt and I conducted involved nothing more than pushing a button on a tape recorder. Talk of that kind makes me, well, just a little annoyed.

February 12, 2008:

More on Buckaroo Bugs

I heard from Thad Komorowski and Milt Gray in response to my February 8 item about Bob Clampett's Buckaroo Bugs (1944). Thad wrote:

I heard from Thad Komorowski and Milt Gray in response to my February 8 item about Bob Clampett's Buckaroo Bugs (1944). Thad wrote:

I agree completely with what you write of Bugs Bunny's character. As much as I dislike the idea of "rules" in any kind of filmmaking, there are just certain things you can't do with Bugs. Yes, Bugs is a "lovable prankster" in [the Clampett cartoons] The Wacky Wabbit, Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid, and even the first six minutes of Hare Ribbin', but not in a horrible cartoon like Buckaroo Bugs. Ripping out fillings and tricking your mentally deficient adversary into jumping off cliffs is fine if your character is Daffy Duck or a random groundhog. But not Bugs.

Milt's response was different:

Regarding Buckaroo Bugs, where Bugs pulls out Red Hot Ryder's gold fillings with a magnet, that gag never bothered me for two reasons: One, Clampett does it quickly and with a light touch, and two, Ryder doesn't react, so there seems to be no pain. In fact, if I were to think of it more literally, I would have to wonder how loose those fillings were in the first place, to be pulled so easily with only a magnet. Perhaps Ryder takes them all out each night, like false teeth, and stores them in a glass of water.

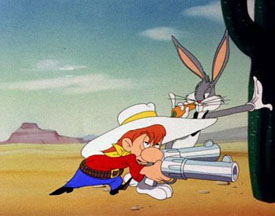

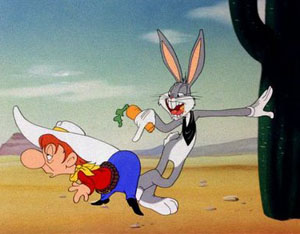

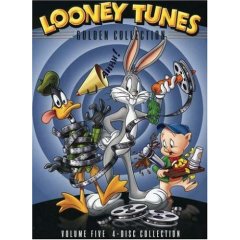

I don't think the notion of a "light touch" is consistent with the sustained closeup of Red Hot Ryder's mouth, which is not a particularly appetitizing sight even when all the fillings are in place. There's a similar gag, which I don't think is particularly funny but is actually handled with a comparatively light touch, at the end of The Wacky Wabbit (1942), when Elmer believes he has removed a gold tooth from Bugs's mouth but has in fact removed one from his own. In that gag we don't have to watch the dental surgery, and it clearly isn't the point of the gag anyway; Elmer's obtuseness is. (The Wacky Wabbit, like Buckaroo Bugs, is part of the new Looney Tunes DVD set, Golden Collection 5.)

I don't think the notion of a "light touch" is consistent with the sustained closeup of Red Hot Ryder's mouth, which is not a particularly appetitizing sight even when all the fillings are in place. There's a similar gag, which I don't think is particularly funny but is actually handled with a comparatively light touch, at the end of The Wacky Wabbit (1942), when Elmer believes he has removed a gold tooth from Bugs's mouth but has in fact removed one from his own. In that gag we don't have to watch the dental surgery, and it clearly isn't the point of the gag anyway; Elmer's obtuseness is. (The Wacky Wabbit, like Buckaroo Bugs, is part of the new Looney Tunes DVD set, Golden Collection 5.)

Thad Komorowski has also offered some pertinent thoughts about The Hanna-Barbera Treasury, and about a David Gerstein book that does the same sort of thing but much better; see Thad's comments on the H-B Feedback page.

February 8, 2008:

On Buckaroo Bugs

My contributor's copy of the latest Looney Tunes DVD set, Golden Collection 5, arrived the other day, and I've been enjoying seeing some of my favorite cartoons looking better than since they were first released. I did audio commentaries for two cartoons in the set, A Tale of Two Kitties (1942) and Buckaroo Bugs (1944), both directed by Bob Clampett.

My contributor's copy of the latest Looney Tunes DVD set, Golden Collection 5, arrived the other day, and I've been enjoying seeing some of my favorite cartoons looking better than since they were first released. I did audio commentaries for two cartoons in the set, A Tale of Two Kitties (1942) and Buckaroo Bugs (1944), both directed by Bob Clampett.

Ricardo Cantoral wrote to take issue with my Buckaroo Bugs commentary, in which I remarked (as I do in Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age) on what seemed to me to be Bugs's very aggressive personality:

Though you provided some interesting facts, I had a problem with one thing, your views on what is the proper characterization of Bugs Bunny. Ever since his creation in Tex Avery's A Wild Hare, Bugs has always been a wiseass character. He really does not fight his opponents at all, he just messes with them. Elmer Fudd, for example, is a bumbling dope who is not even a hunter. Look at how he entered in A Wild Hare. He laughed at the most minuscule things and couldn't even identify Bugs as a rabbit. Bugs was no threat to him at all. So he just screwed with him such as by kissing him and putting a skunk in his rabbit trap. Bugs even let Elmer take a shot at him because he knew he would miss.

Going by this cartoon that is regarded as the definitive characterization, Bugs was indeed in character in Buckaroo Bugs. His "terror" as the Masked Marauder was just him playing with everyone. All he did was steal carrots. He was also just messing with Red Hot Ryder. Just like with his Elmer encounter, he has nothing personal against him. He is like the teenager that threw paper balls at the back of your head in school. He teases people that look silly or stupid just for a laugh, he doesn’t hate them at all.

This is why I also think Jones' characterization of Bugs in the '50s was entirely wrong. He became a smug adult, not a playful teen anymore. And he hated his enemies; he didn't play with them any more. He wanted to teach them a lesson they wouldn't forget. So Bugs didn't feel as appealing as he once was and he slowly did less and less to entertain his audience. He was reduced to making one-liners and just simply moving his eyebrows.

I shared Ricardo's comments with my longtime collaborator Milt Gray, who replied: "I've been

hesitating to tell you all these years that my thoughts on Bugs Bunny are identical to Ricardo's." Gulp! Since I value no one's opinion more than I value Milt's, I watched Buckaroo Bugs yet again.

I shared Ricardo's comments with my longtime collaborator Milt Gray, who replied: "I've been

hesitating to tell you all these years that my thoughts on Bugs Bunny are identical to Ricardo's." Gulp! Since I value no one's opinion more than I value Milt's, I watched Buckaroo Bugs yet again.

I won't defend the Bugs Bunny in Chuck Jones's cartoons of the '50s. In most cases (What's Opera, Doc? being the prime example), what interests me about those cartoons, such as Maurice Noble's designs, lies outside the character of Bugs. And Jones's Bugs toward the end of that decade was indeed insufferably smug, and sometimes insufferably effete to boot.

But Clampett's rabbit in Buckaroo Bugs is, for me, just too damned mean to be a very appealing character. Using a magnet to pull the gold fillings out of Red Hot Ryder's teeth is not the same as throwing spitballs, as I think the accompanying frame grabs illustrate. There's a little too much of the sadist in that Bugs, and not enough of the "playful teen." If he doesn't hate his enemies, that's because he thinks they're too contemptible to be worth the bother. There's a lot about Buckaroo Bugs that I like, especially beautiful animation, but it'll never be one of my favorite Clampett cartoons, much less one of my favorite Bugs Bunny cartoons. When I want to experience the special joys of a Clampett cartoon, I'll watch Book Revue or The Great Piggy Bank Robbery or Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs. But not Buckaroo Bugs.

But Clampett's rabbit in Buckaroo Bugs is, for me, just too damned mean to be a very appealing character. Using a magnet to pull the gold fillings out of Red Hot Ryder's teeth is not the same as throwing spitballs, as I think the accompanying frame grabs illustrate. There's a little too much of the sadist in that Bugs, and not enough of the "playful teen." If he doesn't hate his enemies, that's because he thinks they're too contemptible to be worth the bother. There's a lot about Buckaroo Bugs that I like, especially beautiful animation, but it'll never be one of my favorite Clampett cartoons, much less one of my favorite Bugs Bunny cartoons. When I want to experience the special joys of a Clampett cartoon, I'll watch Book Revue or The Great Piggy Bank Robbery or Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs. But not Buckaroo Bugs.

I prefer the Bugs in a few of Jones's cartoons of the late '40s, when Mike Maltese's influence was at its strongest. I don't find that Bugs, the Bugs of Long-Haired Hare and Rabbit Hood, smug, or a hater. He is instead a grownup rabbit who responds in sly, adult ways to childish provocations by large, dangerous adversaries (he turns music against the arrogant singer Giovanni Jones, for example).

I prefer the Bugs in a few of Jones's cartoons of the late '40s, when Mike Maltese's influence was at its strongest. I don't find that Bugs, the Bugs of Long-Haired Hare and Rabbit Hood, smug, or a hater. He is instead a grownup rabbit who responds in sly, adult ways to childish provocations by large, dangerous adversaries (he turns music against the arrogant singer Giovanni Jones, for example).

That same Bugs is also present in Freleng's mid-'40s cartoons with stories by Maltese, but I think he is fully realized only in Jones's best cartoons with the character. I find him much more complex and interesting than any juvenile mischief-maker could ever be.

February 7, 2008:

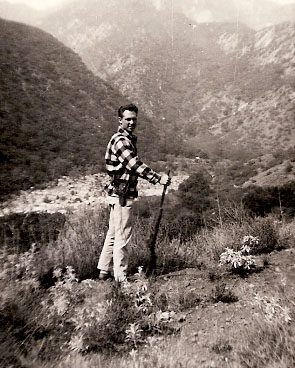

Lloyd Turner, 1947

Four years ago, I posted an interview with Lloyd Turner, a story man for the Warner Bros. cartoons in the mid-'40s and later a writer for Bob Clampett's Time for Beany, the Jay Ward TV cartoons, and Norman Lear's pathbreaking sitcoms. That interview was one of my favorites, and Llloyd was one of my favorite people among the many wonderful cartoon veterans I interviewed while I was doing research for Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age and The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. But the published interview had one glaring deficiency: it lacked any photos of Lloyd. As far as I know, he was never included in any of the cartoon studio's publicity photos.

Four years ago, I posted an interview with Lloyd Turner, a story man for the Warner Bros. cartoons in the mid-'40s and later a writer for Bob Clampett's Time for Beany, the Jay Ward TV cartoons, and Norman Lear's pathbreaking sitcoms. That interview was one of my favorites, and Llloyd was one of my favorite people among the many wonderful cartoon veterans I interviewed while I was doing research for Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age and The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. But the published interview had one glaring deficiency: it lacked any photos of Lloyd. As far as I know, he was never included in any of the cartoon studio's publicity photos.

Janice Munn Johnson has remedied that shortcoming by sending me four photos of Lloyd taken when he was living in Hollywood in 1947. Jan had moved to Hollywood from a small town in Ohio, and she was working for Capitol Records when she and Turner dated. He sent the photos to her after she returned to Ohio, and, happily for us, she kept them for more than sixty years. "He was a very special part of my life, albeit for a very short time," she says. "I know that is why I kept his pictures all these years!"

One of the photos is at the right, and I've added all four of them to the interview. The Turner you see in the photos is the young man whose adventures at the Warner cartoon studio the mature Lloyd Turner described to me in 1989. Many thanks to Jan Johnson for sharing her Lloyd Turner with the rest of us.

Speaking of interviews...

I haven't posted any for a while. Converting transcripts into Web pages is a lot of work, even when (as with the Turner interview) the transcript already exists as a computer file, and I've been happy to seize any excuse not to convert another one. Happily, my new scanner does a better job with typewritten pages than my old one did, and at the urging of Didier Ghez, I'm finally getting back in the interview business. I'm now editing an interview with Jim Bodrero, one of the leading lights in Joe Grant's model department in the early '40s, and more interviews will follow.

February 6, 2008:

Walt in England

No new information has turned up to pinpoint the date and place of the shipboard photo of Walt and Lillian Disney that I posted on January 30, although Walt's daughter, Diane Disney Miller, is sure that the photo was taken aboard one of the "Queens," Mary or Elizabeth, when the Disneys visited England and Ireland in the fall of 1946. That trip followed hard on the heels of the premiere of Song of the South at Atlanta on November 12, 1946. Walt and Lilly evidently took the train from Atlanta to New York after the premiere and sailed from there to England. The Disney Archives' record of Walt's travels shows that he was away from the studio from November 6 to December 18, 1946.

The photo above was taken in England in the summer of 1951, during the filming of The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men. Walt and Lillian's visit to England that summer was the second of the extended trips to Europe they made with their daughters, Diane and Sharon. (The first such trip was in 1949, for the filming of Treasure Island.) That's Robin himself, Richard Todd, at Walt's right, and Maid Marian, Joan Rice, at his left. It was during that summer that Todd and Walt struck up a friendship that I discussed with Todd in our 2004 interview. You can read about that friendship in The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney but not in any of the other Disney biographies; for instance, you won't find Todd's name in the index of Neal Gabler's Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination .

In our interview, Todd startled me by speaking of Walt, obviously without ill intent, as a "social climber." What Todd meant was that he had connections, in England's stratified society, with interesting and high-ranking people whom Walt would have otherwise had difficulty meeting. One of them was Henry Tiarks, a glamorous merchant banker who was married to a West End actress and whose daughter ultimately became the Duchess of Bedford.

Diane Disney Miller remembers that the Disney family was invited to the Tiarks home for lunch. "As I recall," she says, "dad was invited solo first, and went horseback riding with Tiarks around his grounds." (Walt was of course an accomplished horseman, after his years as a polo player.) "Dad was amused when Tiarks indicated a neighboring estate as belonging to 'the fellow who lost us the American Colonies.' He sounded like a sore loser. But mother and dad did enjoy their friendship."

Sometimes the pieces of Walt's life fit together in interesting ways, as with the conjunction of the Atlanta premiere and the voyage to England in 1946. In 1949, when the Disneys went to England for the filming of Treasure Island, they left Los Angeles on Saturday, June 11, 1949, just a few days after the small crisis over the casting of a voice for the title character in Alice in Wonderland, when Margaret O'Brien withdrew and Kathryn Beaumont was chosen in her place. Kathryn's early work on Alice, when she was filmed in live action as a guide for the animators, took place when Walt was out of the country. If she hadn't been available, Walt might have had to face a trip overseas with no voice chosen.

...And Walt in K.C.

[A February 12 update: Jeff Pepper has posted a correction about the Wirthman Building.]

Almost three years ago, I posted a photo essay about the sad current state of Walt Disney's old neighborhood in Kansas City, Missouri. Jeff Pepper, whose 2719 Hyperion is one of the very best—and certainly the most beautifully designed—of all the Disney fan sites, has posted a sort of update, with a number of striking aerial photographs of Walt's neighborhood. Well worth a visit, as is true of Jeff's posts generally. As a bonus, this post has stimulated a charming comment by Diane Disney Miller about one of her father's home movies.

One quibble: Jeff has the Laugh-O-gram studio moving in 1923 from its quarters in the McConahy Building to the Wirthman Building, a few blocks away. That didn't happen, as I've explained on page 36 of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney and in a correction of the same error on page 71 of the Gabler biography. Instead, Walt moved what was left of Laugh-O-grams back to his old quarters at 3239 Troost, over the restaurant called Peiser's. The move to the Wirthman Building is one of those persistent little errors in animation history that I'm sure is never going to go away, like the idea—to switch to the Warner cartoons—that Elmer Fudd evolved out of the Egghead character (they were always two distinct characters).

February 4, 2008:

The Paper Chase

[A February 6 update: Amazon.com notified me in a email yesterday that it now expects to ship the trade paperback of The Animated Man on April 9, considerably later than the February 19 publication date I mentioned below.]

UC Press Amazon.com has for a long time announced today as the date when The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney would be available as a trade paperback, but University of California Press tells me that there has been a problem at the printer and so publication has been delayed. The paperback's current publication date is February 19.

Which reminds me: I'm grateful for the many favorable comments on The Animated Man that have been posted on both amazon.com and bn.com. I've come away from reading those comments feeling that I have a lot to live up to, in what I write on this site and in my future books. I'm very glad to have that kind of incentive.

Remembering Roger

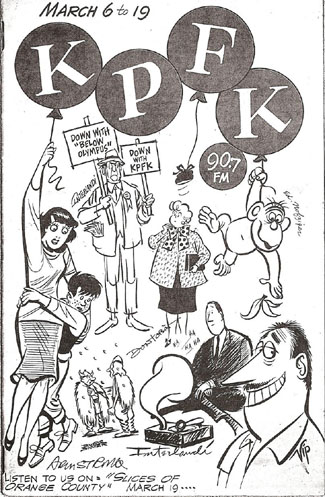

[A February 8 update: Terry Guy tells me that the two Interlandi drawings are in fact by two Interlandis. Phil, the better known of the twin brothers, drew the man seated in front of the antique photograph; Frank drew the angry guy with the signs.]

[A February 8 update: Terry Guy tells me that the two Interlandi drawings are in fact by two Interlandis. Phil, the better known of the twin brothers, drew the man seated in front of the antique photograph; Frank drew the angry guy with the signs.]

Terry Guy wrote after reading my January 31 post about comic books:

Your recent post of Gordon Kent’s recollections of Chase Craig and Roger Armstrong reminded me of the attached oddity, a group illustration done by Roger and some of his Orange County, California cartoonist buddies for the cover of one of the program guides for the radio station where I work, KPFK 90.7 FM in Los Angeles. The illustration was promoting a program evidently featuring the represented artists. Unfortunately, I can’t find a copy of the original publication, so I don’t know what year this dates from… I suspect it was in the early 1960’s. Roger had contacted us in the 1990’s, wanting to know if we might have a recording of the program, which we unfortunately didn’t. I would love to have heard the show myself, but I didn’t arrive in KPFK-land until late 1979.

I had a very nice chat with Roger when he happened to call in to make a pledge during one of our on-air Fund Drives. We talked about cartooning and my own illustrious career in animation, working as an assistant animator on some of Hanna-Barbera’s early-1980’s product. Roger was extremely pleasant and encouraging on the phone, inviting me to come visit him in Laguna Beach if I ever got down there. I never took him up on that invite, regrettably, nor did I ever have another conversation with him. He continued to support KPFK to the end, and I was certainly saddened to hear about his passing.

Roger is represented on that KPFK cover by his drawing of two characters from the Ella Cinders comic strip that he drew for years. The other contributing cartoonists: Virgil Partch, Ed Nofziger, Don Tobin, Burr shafer, and Phil Interlandi. An impressive group.

Terry added a note about his own career in and out of animation. I suspect his history is echoed in the lives of many other people who entered and then left animation when work began to flow overseas:

I’ve met you a few times at ASIFA events when you’ve visited Los Angeles, and I even made it onto your website in a photo you posted from your signing session at the L.A. Times Festival of Books last year. I’m in the background wearing a mint-green KPFK T-shirt and a Nikon. KPFK is a listener-sponsored station operated by the Pacifica Foundation, which also operates WPFW, 89.3 FM in Washington, D.C., and stations in New York, Houston, and Berkeley. We’re not National Public Radio. Our programming is somewhat more radical or “out there” than NPR, although many people likely see us as cut from the same cloth. I fell into a job here when I tumbled out of the animation industry in 1986, when massive amounts of the drawing work was shipped overseas. I realized that KPFK needed me more than the animation business did, so I’ve remained here since, picking up some freelance assistant work now and then (mostly “then”). I’ve contributed a number of my own illustrations for use in our program guide, while we still published one, often for the cover such as the illustration attached here.