"What's New" Archives: April 2008

April 30, 2008:

April 29, 2008:

April 28, 2008:

April 25, 2008:

April 23, 2008:

Did Walt Really "Hate" the Goofy Cartoons?

Børge Ring on Hans Perk and Leica Reels

April 22, 2008:

Disney Comics for the Mature Danish Moppet

April 21, 2008:

Two Days in the Life: Kansas City, 1922

April 20, 2008:

April 17, 2008:

April 16, 2008:

April 15, 2008:

April 10, 2008:

April 8, 2008:

April 30, 2008:

The Jones-Avery Letter

It's one of the most famous/notorious animation-related documents, a 1975 letter from Chuck Jones to Tex Avery (who added his own comments to it) attacking Bob Clampett and the Clampett interview I published in Funnyworld in 1970. I was also a target, but the heaviest barrage by far was aimed at Bob. Chuck and Tex accused him of wildly exaggerating his importance at the Schlesinger studio and, in particular, of claiming far too large a role in the creation of Warner cartoon characters like Bugs Bunny.

It's one of the most famous/notorious animation-related documents, a 1975 letter from Chuck Jones to Tex Avery (who added his own comments to it) attacking Bob Clampett and the Clampett interview I published in Funnyworld in 1970. I was also a target, but the heaviest barrage by far was aimed at Bob. Chuck and Tex accused him of wildly exaggerating his importance at the Schlesinger studio and, in particular, of claiming far too large a role in the creation of Warner cartoon characters like Bugs Bunny.

The Jones-Avery letter, as it's known, was not private correspondence but was intended for wide distribution, and it has been circulating among animation fans and professionals for more than thirty years. The letter has been published on the Web before, and it's now available on Thad Komorowski's site.

In 1992, I wrote an extended piece about the Jones-Avery letter, and the circumstances surrounding it, for the amateur press association called APAtoons. I've now posted that piece on an Essays page called "From 1992: On the Jones-Avery Letter."

In republishing that piece, I've made a few small editorial changes, for the sake of clarity, but I didn't see anything of substance that I thought required revision.

The Clampett interview itself is at this link, and the Jones interview from Funnyworld is at this one.

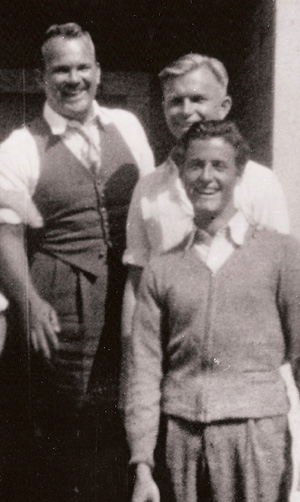

The accompanying photo is of Avery, Jones, and Clampett at "Termite Terrace," the frame building on the Warner Bros. Sunset Boulevard lot that housed the Avery unit in the summer of 1935.

April 29, 2008:

More Goofy Talk

My April 23 and April 25 posts about Walt Disney's attitude toward Goofy, and especially about his efforts to recast the character through a "foibles" series in the early '50s, stimulated this response from Will Hamblet:

My April 23 and April 25 posts about Walt Disney's attitude toward Goofy, and especially about his efforts to recast the character through a "foibles" series in the early '50s, stimulated this response from Will Hamblet:

Was Motor Mania the one about mild-mannered Mr. Walker and his alter ego, the crazed Mr. Wheeler? If so, I thought it was hilarious when I saw it in a theatre many decades ago. Of course, I was barely pubescent at the time and my tastes have obviously changed over the years. Was I wrong? Sounds like it from your discourse ... or am I just interpreting it incorrectly?

Yep, that's the one, the first of the "foibles" cartoons—and I think it is indeed better than most of the others, because it bears a closer resemblance to Jack Kinney's best Goofy sports cartoons, like How to Play Football, than the later ones do. As in the best sports cartoons, Goofy in Motor Mania is not so much a character as an interchangeable part in a series of flashy and funny gags. Only the too-obvious message about driving safely pulls Motor Mania down. It was in the later "foibles" cartoons, as Kinney tried to restore to Goofy more of a personality (in accordance with Walt's wishes), that the bottom fell out.

Generalizing about the Goofy cartoons is tricky, though, as Thad Komorowski has reminded me:

There actually seems to be even more of an attempt to instill character into Goofy in earlier cartoons. The Art of Skiing, How to Play Baseball, and other early Kinney entries seem to try and cram in that "Disney timelessness" by making the gags take way too long to build up, pretentiously drawing attention to how skillfully crafted the animation is (I feel the same way, though more strongly, about many other Disney cartoons). I can cut some slack in these cases, though, because at least every drawing is unique and funny.

I don't think that the "foibles" were all necessarily failures. I enjoy Father's Day Off for its pervertedness that few other Disney cartoons offer, and For Whom the Bulls Toil was at least an attempt to do something unique with a subject that's more cruel than funny. And I think more of the blame should be placed on Kinney (whose timing was getting a little stodgy by that time) than Walt for those films' failures. But after all, wouldn't you be sick of the same character after so many years, too?

Over any span of a few years in the '40s and early '50s, there were always a few cartoons in the Goofy series that didn't fit the then-current mold, either in subject matter or in handling. It took Kinney a while to bring the sports cartoons to something close to perfection (which is what I see in Football, Hockey Homicide, and Goofy Gymnastics), and he made some slow-moving duds ( Tennis Racquet) even after he'd mastered that formula. And although the "foibles" cartoons are mostly dull situation comedies, there are funny bits scattered through them, so they can't be written off entirely. Generalizations are, as always, suspect, even though they're unavoidable.

Probably it would have made the most sense for Walt to retire Goofy when the sports series had run its course; that, or to leave him as the non-character he was in the best of the sports cartoons. But I can understand why Walt didn't want to do that; and I can understand his frustration when his preferred solution didn't work.

Probably it would have made the most sense for Walt to retire Goofy when the sports series had run its course; that, or to leave him as the non-character he was in the best of the sports cartoons. But I can understand why Walt didn't want to do that; and I can understand his frustration when his preferred solution didn't work.

Thad's remark about the "skillfully crafted" animation in the early Kinney sports cartoons reminded me of a note I made to myself years ago, about the animation in Motor Mania:

As so often in the Disney cartoons, expert bits of animation pop up where there is no reason to expect them; they seem to be there simply because that is the kind of animation the Disney people always did. An example: Walker has been hit by a car; he lands on his head, slumps down on his shoulders, falls over forward so that his feet hit the ground, and pulls himself up into an upright position—an utterly natural-looking although highly improbable action.

By John Sibley, surely, although I don't have the draft and other people are much better at such animator identifications than I am.

April 28, 2008:

Censoring the Eleven

I'm quoted in the New York Times today on the "Censored 11," the Warner cartoons that have been barred from distribution because of their racial stereotypes but that keep showing up on YouTube and other places online. My quotes are of course only fragments from a much longer interview (which lasted around an hour, I think).

One point I made to Dan Slotnik that I don't think is made often enough is that most of the "Censored 11" are such bland duds that it takes a lot of effort to be offended by them, whereas the two really good cartoons, Bob Clampett's Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs and Tin Pan Alley Cats, have so much artistic merit that they demand to be seen despite their undeniable use of stereotypes. Only two or three of the eleven are truly problematic, because their stereotypes are so pointed and cruel—I'm thinking mainly of Chuck Jones's Angel Puss and Tex Avery's All This and Rabbit Stew—and the cartoons aren't much good otherwise.

The "Censored 11" are not at all alike, in other words, and the handling of them should reflect their differences. But I'm afraid that to discriminate, if you'll excuse the expression, among the eleven with anything like careful thought is beyond the capabilities of the minions at a corporate behemoth like Time Warner.

April 25, 2008:

Will Eisner Online

Dana Gabbard reports:

Dana Gabbard reports:

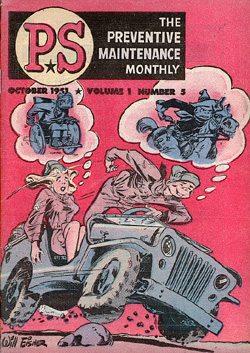

Virginia Commonwealth University has created a digital collection of its holdings for PS Magazine during the years Will Eisner did art for it (1951-1972). This magazine was part of an effort by the Army to encourage soldiers to keep better care of their equipment. It was a digest-sized publication focusing on preventive maintenance with each issue consisted of a color comic book style cover; eight pages of four color comic continuity story in the middle; and a wealth of technical, safety, and policy information printed in two color. Presented are complete scans for 145 regular issues, 3 special issues, and 14 index issues. There are over 8000 scanned pages in the collection.

Kudos to the folks at VCU who made this possible: Sam Byrd, (Digital Repository Librarian) and Susan Teague Rector (Web Applications Manager) and their respective staffs.

And if you don't know who Eisner was, or why some of us take him so seriously, you may want to read my Essay called "Moved by the Spirit."

Mirroring Nature—Or Not

From Don Faber, a link to a New York Times article about The Idea of Nature in Disney Animation, a new book by the British academic David Whitley that takes Bambi as its starting point. I can't imagine ever reading this book—life is much too short—but I find it fascinating that a 66-year-old Disney cartoon can still trigger so much talk. The Times quotes the book:

From Don Faber, a link to a New York Times article about The Idea of Nature in Disney Animation, a new book by the British academic David Whitley that takes Bambi as its starting point. I can't imagine ever reading this book—life is much too short—but I find it fascinating that a 66-year-old Disney cartoon can still trigger so much talk. The Times quotes the book:

[The Disney] films have taught us variously about having a fundamental respect for nature. Some of them, such as Bambi, inspired conservation awareness and laid the emotional groundwork for environmental activism.

Well, maybe. The portrait of nature in Bambi is too wildly at odds with the facts of life in the wild for me to credit it with any enduring impact on serious concern for the environment. The kids who left the theater sobbing about the death of Bambi's mother were bound to learn about the real sex life of deer sooner or later; not to mention learning that properly prepared venison is delicious.

Walt's later True-Life Adventures, so often derided, actually depict a much more believable natural world, sometimes disconcertingly so, as in a film like Jungle Cat, in which various animals spend all their waking hours striving furiously to eat one another. Had Bambi been made in the same spirit, Friend Owl would have been snacking on those sweet little bunnies. And if you thought the death of Bambi's mother was traumatic...

Walt, Jack, and Goofy

Eddie Fitzgerald writes in response to my April 23 posting about Walt Disney's attitude toward the Goofy cartoons.:

I am so sorry to hear that Walt didn't like Kinney's Goofys, and that Kinney himself had misgivings about them. The best of the Goofy sports cartoons, the ones about baseball, ice hockey, football, basketball, and tennis, contain some of the best-executed funny animation the studio ever did. John Sibley, who animated some of the best scenes, was one of the greatest funny animators ever. I got into the animation business partly because I liked these cartoons so much.

If Walt didn't like the Kinney Goofy because they didn't give him something he could exploit at the park, then that sends a shiver up my spine. They were funny and imaginative cartoons which firmed up the public's belief that the Disney studio was home to imaginative and cutting edge animation. Surely that has a dollar value, if only indirectly.

That's a misreading of what I wrote, and of what Walt and Kinney thought. The Goofy cartoons that nobody much liked were the "foibles" cartoons of the '50s (Motor Mania, How to Sleep), not the often very funny sports cartoons of the '40s (most of which Kinney directed, although Double Dribble was directed by Jack Hannah). And "exploitation at the park" certainly wasn't a factor in 1948, when Walt ordered the shift to the "foibles" series. He thought the sports suitable for cartoons had been covered, and I can't quarrel with that, and he thought, incorrectly as it turned out, that the "foibles" series could bring Goofy back to life as a personality, but a more modern personality than the Goof of the '30s.

That's a misreading of what I wrote, and of what Walt and Kinney thought. The Goofy cartoons that nobody much liked were the "foibles" cartoons of the '50s (Motor Mania, How to Sleep), not the often very funny sports cartoons of the '40s (most of which Kinney directed, although Double Dribble was directed by Jack Hannah). And "exploitation at the park" certainly wasn't a factor in 1948, when Walt ordered the shift to the "foibles" series. He thought the sports suitable for cartoons had been covered, and I can't quarrel with that, and he thought, incorrectly as it turned out, that the "foibles" series could bring Goofy back to life as a personality, but a more modern personality than the Goof of the '30s.

Walt believed, quite reasonably, that characters with distinct personalities (Donald Duck being an obvious example) lent themselves better to merchandising, but I think that was secondary to his strong preference for such personalities in the cartoons themselves. Goofy in Kinney's sports cartoons is not such a personality; he's barely a character at all, especially in the best of those cartoons, the ones with hordes of Goofys of varying sizes and shapes (How to Play Football, Hockey Homicide). Almost needless to say, Kinney made many of his best cartoons with little input from Walt, who was preoccupied with war-related filmmaking.

April 23, 2008:

Did Walt Really "Hate" the Goofy Cartoons?

Neal Gabler, writing about the Disney studio in the postwar years, says on page 422 of Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination that "Walt absolutely hated the Goofy cartoons, threatening constantly to terminate them before relenting, largely to provide work for the animators—yet another example of Walt's vacillation under the financial exigencies."

Mark Kausler wrote in response to my recent suggestion that Gabler erred:

Maybe Walt liked Goofy in the 1930s, but according to Harry Tytle's book, One Of "Walt's Boys," Walt's attitude toward Goofy changed with the years. Page 26: "The new Goofy also received adverse comment from Walt; he just was not a fan of the revised Goofs. Walt wanted the dangly, dog-like ears back on Goofy. He felt the character did not aid in the studio's merchandising effort. And he said, in later years, that Goofy lacked character." On pages 83-92, Harry goes into a history of the Goofy shorts, with this note on page 87: (Oct. 3, 1950) "Walt feels...The Goof is not a good character, no good for merchandising and the audience never identifies with him." I think there are a few other negative mentions of Goofy in connection with Art Babbitt (pages 93-95), but I think Walt's attitude to the character is clear from these pages.I'm using this book as possibly the source where Gabler derived his opinion that Walt did not like Goofy, a half-truth I guess.

I have Tytle's book, which was published in a limited edition in 1997, and I think it's the likely source for Gabler's statement (Gabler himself doesn't cite a source). But I don't see anything in the book to suggest that Walt "absolutely hated" the Goofy cartoons, or, for that matter, that he kept the Goofy shorts alive only to provide work for the animators. As Tytle makes clear, the Disney short cartoons, the Goofy shorts included, were a threatened species for years before the studio finally stopped making them. If the Goofy cartoons were more vulnerable than the Donald Duck shorts, that was surely because Goofy was a less popular character than Donald. (The Mickey Mouse series faded away even before the Goofys; does that mean Walt hated Mickey?)

Ironically, Walt himself contributed materially to the deterioration of Goofy as a character, by coming up with the idea for what the story man Milt Schaffer called the "foibles series"; it began in 1950 with Motor Mania, directed by Jack Kinney. "This was Walt's idea," Schaffer told Milt Gray in 1977. "He called us up there one time and said, 'I want to make pictures on the foibles of man, and you guys are going to do it.' So we did things on dieting, giving up smoking, the problems of raising children...we did quite a few of them." And I don't know of anyone who would argue that those cartoons are much good.

Kinney himself told me in 1973 that Walt "got on this psychological kick for some reason or another, and I had to do pictures I didn't really want to do. ... I said, 'Jesus, Walt, if you're going to do that, make him a human character, take the dog head off of him.' He said, 'Yeah, let's try that.' Then, about an hour later, he called back, 'No, no, the Goof's established, they know him.' But those pictures were disasters, because I didn't fight it hard enough."

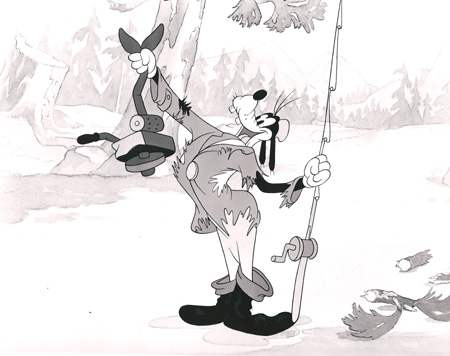

Tytle confirms on page 86 of his book that the "foibles" idea was Walt's. Walt wanted to put "personality" back into Goofy, but Kinney had already transformed Goofy into a crowd of extras in comic spectacles like How to Play Football (1944). (The publicity-still image above is from an earlier Kinney cartoon, How to Fish [1942]). The transformation had occurred when Walt wasn't paying much attention to the shorts, and by 1948, when he came up with the "foibles" idea, there was in effect no Goofy personality left to revive. Kinney's conception of the character had triumphed, as a few tentative counter-efforts in the mid-'40s, like The Big Wash, had already demonstrated. The "foibles" version was never more than a watered-down version of Kinney's frenetic Goof of the early '40s.

I think what bothers me most about Gabler's statement is its suggestion that Walt thought about his characters—and his films, for that matter—as a fan might. I think he had a much more objective view of them. (When he said that Kinney's Goofy was "no good for merchandising and the audience never identifies with him," he was absolutely right, however funny the Kinney cartoons were.) Consider Bambi and Alice in Wonderland; by all accounts he loved the former and didn't care for the latter, which he complained was full of "weird characters." Yet it was some of those weird characters who became costumed denizens of Disneyland, and an Alice ride has been part of the park since 1958. Has there ever been a trace of Bambi in Disneyland? I can't think of any. Walt knew that Alice lent itself to conversion into a park attraction, but Bambi didn't. That was what mattered, not his feelings about the two films.

More Updating

Walt's Lawyer: Gary Parker wrote earlier this month about Neal Gabler's Disney biography and his encounter with a former Disney attorney who was reading it. I've added a note to my post of Gary's message, identifying (probably) that lawyer and adding some thoughts about an occasion when Walt may have been, in fact (and for understandable reasons), "very rough and demeaning."

Giddins on Disney: Gary Giddins has an excellent reputation as jazz critic and biographer (of Bing Crosby), but now he written with surprising enthusiasm about the Disney Latin American features of the '40s, Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros (both about to be reissued on a single DVD). You can read his piece in the New York Sun by clicking here. Thanks to Don Faber for the link.

Giddins on Disney: Gary Giddins has an excellent reputation as jazz critic and biographer (of Bing Crosby), but now he written with surprising enthusiasm about the Disney Latin American features of the '40s, Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros (both about to be reissued on a single DVD). You can read his piece in the New York Sun by clicking here. Thanks to Don Faber for the link.

Access v. Understanding: Dana Gabbard wrote to take polite issue with my comment in an April 20 post that "the wealth of important historical material now available for study on the Web is simply astounding, especially to those of us who spent decades gathering information that is now available with just a few clicks of the mouse":

While true enough, simple access doesn't give one the ability to understand what you are looking at and its connections, meanings, etc. Judgment (whether via the old methods or now while touring the web) takes time and experience. Far too often people assume and jump to conclusions without sufficient context, etc. The web is full of opinions unimpeded by the thought process (to borrow a phrase I heard years ago). My friend Joe Torcivia once lamented to me we fans who spent years of study etc. learning about our passions are relics, un-needed now that the net makes so much readily available. I retorted we are now needed even more.

Dell Comics Subscriptions: Also from Dana Gabbard, a link to a full-color PDF version of Maggie Thompson's "Beautiful Balloons" column in The Comics Buyer's Guide. Earlier this year, I speculated about the economics of the subscriptions that Dell comic books like Walt Disney's Comics & Stories and Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies Comics hawked so energetically in the '40s and '50s. Maggie did some inspired digging, and she learned that those subscriptions made far more sense for the publisher than I ever would have dreamed (rock-bottom second-class mailing rates being a big part of the reason).

Børge Ring on Hans Perk and Leica Reels

Børge Ring, the great Danish animator, recently shared with me this charming anecdote about Hans Perk, whose Web site does so much to preserve and promote Disney history:

You have often praised Hans Perk for his dedicated field work in Disney archeology. I jokingly call him The Cairo Museum, always out there in the Valley of the Kings pushing the toothbrush.Since you know him as person by now, there is an early instance of his dedication I have often wanted to tell you about. It is not written for your blog but feel free.

Hans was 18 or something and my apprentice. I worked at a personal film called Anna & Bella [winner of the Academy Award for best short cartoon of 1985] on and off between commercial jobs. After a strenuous period including much travelling I sat down to resume the beloved project. Hans said: "Isn't it time for a Leica reel?" "Oh no, Hans. I want to go straight into layout and timing. I am starved." But Hans at 18 felt that life owed him a Leica experience. "May I borrow the storyboard?" "Sure." He took the brush-inked storyboard home that night, and shot it on his 16mm camera, giving each drawing one frame of film. He developed the negative and stuffed it back into his camera, accompanied by a fresh reel of unexposed film. His camera must have looked like a kid wearing two winter coats.

Shooting with underlight, he ended up with a positive. Next morning he showed up with the positive "print" and a flimsy hand-driven children's film projector inviting me to run the film. I wasn't interested that morning. After decennia of joyfully animating on other people's films I had just simply forgotten what a delightful instrument a detailed Leica can be. The only trustworthy futurology known of. One should never discourage a child who shows initiative. And so I patiently took the tiny bentwire handle between my forefinger and thumb and cranked cautiously: knik knak. One frame—one drawing. I soon discovered that I could really preview; and with timing, by varying the length of each frame, and I began exploring this all-important aspect.

Afterwards I felt humbled and grateful to "the wilful child." The story sang its song alright, but I caught a superfluous sequence plus a cut where things briefly veered off. Following Dick Huemer's advice I rearranged the order of four scenes and added a two-feet closeup. I humbly asked Hans if it could be at all thinkable to add a correction to the reel. It could. Reviewing the reel revised by one correction gave me a kick and I became greedy. After two more corrections (they had meant reshooting the first reel three times) everything was smooth sailing and I was once again a true believer in Leica reeling.

April 22, 2008:

More Coal Black Talk

Has there ever been another animated short that stirred up so much controversy, especially one that has been out of circulation, legally, for decades? I can't think of any. I keep hearing from people who like and dislike Bob Clampett's most famous/notorious cartoon, Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs. You can go to the most recent additions to the Clampett Feedback page, and read some perceptive comments from Vincent Alexander, Michael L. Jones, and Ricardo Cantoral, by clicking here.

Disney Comics for the Mature Danish Moppet

A friend shared with me these panels from Danish Disney comic books, in which Bornworthy the Saint Bernard reveals that Disney animals have bodily functions, the Phantom Blot adopts a distinctly kinky persona, and Gyro Gearloose, who has been accidentally transformed into a woman, tests his new status by applying hand to chest. I don't know of anything so, um, progressive in the American Disney comic books.

Remembering Ollie

The tide of tributes to the late Ollie Johnston is receding now, a little over a week after his death, but I want to take a moment to acknowledge a few people who actually had something interesting to say about that good man.

John Canemaker, on Cartoon Brew, and Brian Sibley, on his own blog, offered eloquent eulogies from what I've come to think of as the High Church branch of the Disney faith. I'm afraid that I am, by comparison, snake-belly low—my tongue would cleave to the roof of my mouth were I to say anything good about Robin Hood or The Rescuers, Ollie's animation included—but John and Brian are such gentlemen that they make me want to believe.

(Canemaker has also contributed a memorial essay to the April 22 Wall Street Journal.)

Also on Cartoon Brew, Brad Bird wrote about Ollie with the point and intelligence and good humor we've come to expect from his Pixar features. I particularly liked this passage, in which Bird quoted Milt Kahl:

In spite of the usual “one happy family” picture that public relations always wants to paint about production teams, Disney’s Nine Old Men were competitive with each other. They would help each other out, but like all artists, they had differences of opinion on how best to approach their work.

Milt’s complaint about Ollie’s work was “There are no extremes! His scenes are all inbetweens!”.

This is, of course, wrong.

Actually, Kahl was, from his point of view, precisely, insistently right—which he often was, thus annoying a great many people. Compared with Kahl's best work (and Frank Thomas's), Ollie's work was "all inbetweens," that is to say, softer and less sharply focused. Only by comparison, of course; but that's what comparisons are for.

Ollie's death has been the occasion for a few broader meditations on the "nine old men," the Disney animators of whom Ollie was the last, and on their role at the Disney studio and in animation generally. I particularly liked Mark Mayerson's post and Jenny Lerew's comment about it.

April 21, 2008:

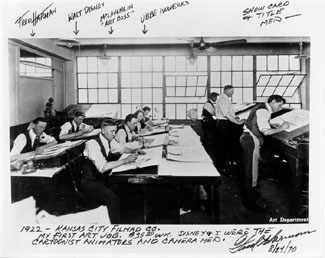

Two Days in the Life: Kansas City, 1922

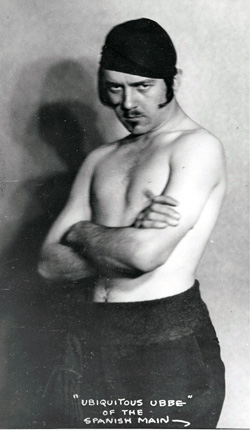

The young man at right may not look familiar at first, but look again: it's Ub Iwerks, who is familiar to us as the master animator at the early Disney studio in Hollywood and then as Disney's resident technical wizard—but not as a glowering pirate.

The young man at right may not look familiar at first, but look again: it's Ub Iwerks, who is familiar to us as the master animator at the early Disney studio in Hollywood and then as Disney's resident technical wizard—but not as a glowering pirate.

This is one of the gag photos that Iwerks and his friends Hugh Harman and Rudolph Ising produced when they were all very young Kansas Citians, working for Walt's Laugh-O-gram studio at first and later trying to start a studio of their own. I have photos of Harman and Ising in similarly outlandish poses.

Such Kansas City photos are some of the most endearing and revealing of the relics from that early phase of what eventually became Hollywood animation's golden age. They speak, as nothing else does, of the youth and energy and ambition of Walt Disney and the people who surrounded him almost ninety years ago.

I've assembled five Kansas City photos, taken on two different days in 1922, for a new Essays page on the "day in a life" theme. You can visit it by clicking here. I'm working on more "day in the life" pages. Next up, probably, will be one devoted to some of what was happening at the Schlesinger studio on one day in 1941.

April 20, 2008:

When Rudy Met Walt, Cont'd

In a March 26 posting, I reproduced a classified ad from the Kansas City Star for Sunday, February 5, 1922, under the "educational" heading. It invited aspiring cartoonists and art students who wanted to "study motion picture cartooning" to come that afternoon to Kaycee Studios at 3241 Troost. That ad was placed by the 20-year-old Walt Disney, who was then in business as Kaycee Studios, moonlighting from his job at Kansas City Film Ad.

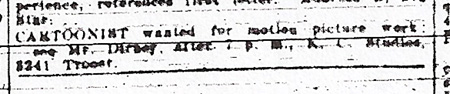

I thought it was probably that ad that led to the hiring of Rudolph Ising, a few months before Walt moved his studio a few blocks away and went into business as Laugh-O-gram. But now I think a different scenario was more likely. Tim Susanin and I have continued scanning the want ads in old Kansas City newspapers, and a few days ago I found this one, under the heading "Help Wanted - Male" on page 13 of the Kansas City Times for Wednesday, March 8, 1922:

The microfilm is murky, and my printout no less so (and the library's large-print microfilm machine was out of commission, unfortunately), but here's what the ad says: "CARTOONIST wanted for motion picture work: see Mr. Dirney [sic]. After 7 p.m. K.C. Studios, 3241 Troost." Walt probably phoned in this ad (as the Times invited its readers to do); that would account for both the misspelling of his name and the identification of his business as "K. C. Studios," rather than "Kaycee," the name on the door. Walt had to interview applicants after 7 p.m. because he was still working days at Kansas City Film Ad.

So, was this the ad that Rudy Ising saw? And was the earlier ad the one that Walt himself spoke of, the one that attracted the student cartoonists who helped him make his first Laugh-O-gram fairy tale, Little Red Riding Hood? The evidence so far points toward "yes" in both cases. Tim reviewed the Star for the last few months of 1921, and since he found no other "educational" ads like the one on February 5, that ad may well have been Walt's first appeal for student helpers.

There were, however, at least four dailies in Kansas City in the '20s. Although the Star and the Times were under common ownership (as were the Journal and the Post), it's probably assuming too much to assume that any ad that appeared in the Star also appeared in the Times. So there's quite a bit more microfilm to be checked. Curiously, the issue of the Times in which I found Walt's March 8 ad was on a microfilm reel otherwise made up of the March 1922 issues of the Star. There was no March 8 Star on the reel.

If it turns out that the two want ads I've uncovered so far are the only such Kaycee Studios ads, that will dispose of some lingering questions but also raise some others: Where did Walt and his student cartoonists work on Red Riding Hood, and did they complete it before Walt ran his March 8 ad? As I noted in my earlier posting, Rudy Ising remembered working only with Walt and Red Lyon, the cameraman, after he was hired; and it seems unlikely that Walt worked on Red Riding Hood in the family garage, given that his parents had moved to Oregon in the fall of 1921. There seems to be no record of Elias Disney's selling the home at 3028 Bellefontaine Street, and I suppose it's at least conceivable that Walt used the garage after someone else moved into the house, perhaps as a renter—but why would he have done that when he had space at 3241 Troost, his second-floor studio above Peiser's restaurant?

It's conceivable that Walt completed Red Riding Hood in a little over a month if (1) he had already done a fair amount of work on it by himself, and (2) he had enough student cartoonists that he could divide the remaining work among them into small parcels that could be completed in a few weeks. But if he had that many aspiring cartoonists helping him make that cartoon, why did none of them ever come forward in later years to reminisce for a reporter about their early involvement with Walt? We have the recollections of many people who worked with Walt in the '20s, at Kansas City and in Hollywood; was there ever anyone who spoke of working on Red Riding Hood?

And why, when Walt incorporated Laugh-O-gram Films in May, did he identify the new company's one completed cartoon as The Four Musicians of Bremen, rather than Little Red Riding Hood? Was he concerned about alerting his former students that he was going to sell the film that was the product of their unpaid work?

And another question: Why do I find detective work of this kind so enjoyable? After all, the general shape of Walt's life and career has been clear for a long time, with Walt himself a remarkably accurate and consistent source. But a lot of details remain to be filled in, and as they are, our understanding of Walt's career, and of Walt himself, will almost certainly change, so that both man and work emerge with richer colors and subtler shadings; an interesting man will become even more interesting. I think it entirely possible, for example, that we will come to see the young Walt, the proprietor of Kaycee Studios and Laugh-O-gram, as a highly aggressive entrepreneur who may have been a little too willing to cut corners in the pursuit of success, but who matured over the course of the '20s and early '30s, becoming an altogether more admirable person as he became not just an entrepreneur but also an artist.

Walt's Skeptical Supervisor

Reminiscing for Pete Martin in 1956, Walt Disney remembered his immediate supervisor at Kansas City Film Ad as a man who found the young Walt "a little too inquisitive and maybe a little too curious. ... He was kind of sore at me, because I think he felt the boss [A. V. Cauger] paid me too much."

Reminiscing for Pete Martin in 1956, Walt Disney remembered his immediate supervisor at Kansas City Film Ad as a man who found the young Walt "a little too inquisitive and maybe a little too curious. ... He was kind of sore at me, because I think he felt the boss [A. V. Cauger] paid me too much."

There's posted on the Fred Harman Museum's Web site a photo of the Film Ad art staff that includes Harman, Walt, Ub Iwerks, and that suspicious "art boss," whom Harman identified as "McLaughlin" in notes he dated August 27, 1970. (The photo as posted on the Harman site is just above, and you can see it reproduced on a larger scale on page 36 of Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney, by Russell Merritt and J. B. Kaufman.) When I tried to track down "McLaughlin's" full identity, online and with the help of the Kansas City Public Library, I came up empty, even after trying some variant spellings.

Tim Susanin had better luck. In reviewing the Kansas City Star and Times for October 1921, he found a want ad for a cartoonist in the Star for October 29-31 and the Times for October 29 and 31 (the Times didn't publish on Sundays). The ad reads: "CARTOONIST and commercial artist wanted; experienced in brush work. J. E. MacLachlan, Kansas City Slide Co., 2449 Charlotte." (The Slide Company changed its name to the Film Ad Company around this time, I still don't know exactly when.)

With an accurate spelling in hand, online sources quickly yielded the basic facts about James Edward MacLachlan. He was a native of Canada, born there on January 7, 1879, and he had somehow lost his right leg below the knee. He was living in Detroit with his wife and four children in 1910, working as what a census taker called a "sign writer." By 1920, when the census found him renting on 31st Street in Kansas City and working in motion pictures as an "artist," there were five children.

It's not at all surprising that this middle-aged man with a physical handicap, a large family, and what may have been a rather tenuous hold on his job (he is, after all, working right alongside his much younger subordinates in that photo) found a bright young whippersnapper like Walt Disney a disturbing presence in his art shop.

And what about that ad? Was MacLachlan trying to fill a vacancy left by Fred Harman's departure? Very hard to say, although that "experienced in brush work" is suggestive, given Harman's skills in that area. Harman's own memories of his association with Walt and with Kansas City Film Ad were too vague and obviously unfactual to be of much help, unfortunately.

Updating

Walt and Selznick: Mark Mayerson suggests, in regard to my April 16 post about the photo of Walt Disney with David O. Selznick, that it was probably taken around the time Selznick began releasing through United Artists, which was handling the Disney cartoons in the mid-'30s: "Selznick started releasing through United Artists in April 1936 with Little Lord Fauntleroy. As Disney was still with UA at that time, perhaps the photo dates from that year. Maybe the photo was publicity trumpeting Selznick joining UA." That sounds plausible to me, although I'd love to pin down the date and exact circumstances of the photo.

Dalmatians Spotted: Speaking of Mark Mayerson, anyone who admires the Disney feature One Hundred and One Dalmatians should be visiting the pages on which Mark has been posting more of his remarkable "mosaics," made up of frame grabs (one per scene) from that film, with animation credits and commentary. Those animation credits have been derived from the draft, or scene-by-scene breakdown, than Hans Perk recently finished posting at his site. To round out the picture, Michael Sporn has posted photostats of Bill Peet's story sketches, lent to him by John Canemaker. As I'm sure I've said before, but it bears repeating, the wealth of important historical material now available for study on the Web is simply astounding, especially to those of us who spent decades gathering information that is now available with just a few clicks of the mouse.

April 17, 2008:

Bob 'n Ollie

Terry Guy sent the remarkable photo above, of Bob Clampett and Ollie Johnston and Bob's wife, Sody, and explained how he came to take it:

The coincidence of Ollie’s death and your posting of it along with a post about the continuing Coal Black controversy prompted me to dig out the attached photo. I shot this obviously unposed image in the early '80s at one of the annual ASIFA-Hollywood Animation Art Festivals that used to happen…well, annually, out here in the San Fernando Valley. This one was in the still-new Sherman Oaks Galleria, and shows Bob Clampett sitting next to Ollie Johnston, with Mrs. Clampett leaning in between them. Out of the picture, Frank Thomas was sitting on the other side of Ollie. Every time I look at the picture, I can't help but wonder about what kind of conversation Bob and Ollie might have gotten into…or if they got into any conversation with each other at all. That in turn raises the larger question that's rolled around in my head for years, about how conscious the Disney artists were of the work done by animators at the other studios, as the cartoons from other places got more polished and funnier, while Disney’s cartoons grew more mannered. Even though I obviously got close enough to these guys to snap the photo, I was too shy to try to ask them a question like that.

The ASIFA Art Festivals were great events, with displays of drawings and cels and other animation ephemera, some of it for sale, some for exhibit only, and lots of animation personnel would be on hand to meet and greet the fans and unsuspecting shoppers at the malls where these events were usually held. Rather jarring was observing how taken not only children, but some adults as well, were with meeting people dressed up as Yogi Bear and Scooby Doo. Voice actors Bill Scott, June Foray and others would perform bits of scripts, and artists would give autographs and also do commissioned sketches for sale. One of the great regrets of my life is that at one of these I asked Ward Kimball to do a drawing of Casey Jr. for me, and then I changed my request to a drawing of Goofy instead. I don’t know what possessed me; instinctively, I knew I would have preferred the Casey Jr., and Ward probably would have enjoyed making that drawing more as well. Anyway, at least I have an original Kimball drawing stuck somewhere in my apartment, albeit of a character that Neal Gabler says Walt Disney hated (an assertion I’d never heard even a hint of anywhere else… do you know if this has any basis in fact?).

Despite the soullessness of the animation in the Disney films of the late '60s and the '70s, I have to admit that it was thanks to seeing The Jungle Book in a theater during a summer festival of Disney films in the '70s that I decided that I wanted to become an animator. I reran scenes from the film over and over in my mind as I lay in bed the night I saw the film, marveling at the movement, thinking how great it would be to do that. I don’t know if any of those scenes I fixated on were Ollie’s, and The Jungle Book hasn’t been a film I’ve watched repeatedly since then, but its display of virtuosity at some level certainly had a profound effect on my life.

I’m glad Ollie lived a long and fruitful life and didn't wind up as one of those people I’m angry at for dying way too soon.

After talking with a lot of Disney people over the years, I can safely say that most of them looked upon other studios' cartoons with benevolent condescension. Here's Dick Huemer, as I quoted him on page 402 of Hollywood Cartoons, saying that even when he and his colleagues liked another studio's cartoons, they had no desire to emulate them: "It was like admiring the kind of a dame that you wouldn't introduce to your mother."

As for being inspired as a child by The Jungle Book, I have no problem with that, given the high level of skill embodied in its animation. But The Jungle Book is, to me, the kind of film a person should outgrow as he or she sees more movies, animated and live action, and learns more about life and all that sort of thing. You may remain very fond of The Jungle Book, and if it ignited a passion for Disney animation, why not? But if, forty years after you first saw The Jungle Book, you still want to make films just like it, I'm sorry, but "arrested development" is the phrase that leaps to mind.

As for Gabler's assertion that Walt hated Goofy...that's yet another statement in his Disney biography that I should add to my already very long list of its errors.

April 16, 2008:

Where's Walt, No. 7

He's with David O. Selznick, of course, but what was the occasion for Walt and the producer of Gone With the Wind getting together? They were founding members of the Society of Independent Motion Picture Producers in 1942, but this photo appears to have been taken a few years earlier than that, sometime in the mid-1930s.

Gotta love Walt's shoes. Betcha Selznick was jealous.

April 15, 2008:

On Ollie Johnston

I first met Ollie Johnston, who died yesterday at the age of 95, in October 1976, when I interviewed him and Frank Thomas over lunch at the Disney studio's commissary. I next saw him when the Johnston and Thomas families—Ollie and his wife, Marie, and Frank and his wife, Jeanette, and their son Doug—visited Washington, D.C., the weekend of June 18-19, 1977, for the premiere at the Kennedy Center of The Rescuers.

I first met Ollie Johnston, who died yesterday at the age of 95, in October 1976, when I interviewed him and Frank Thomas over lunch at the Disney studio's commissary. I next saw him when the Johnston and Thomas families—Ollie and his wife, Marie, and Frank and his wife, Jeanette, and their son Doug—visited Washington, D.C., the weekend of June 18-19, 1977, for the premiere at the Kennedy Center of The Rescuers.

The day before the premiere, I drove with the Johnstons and Thomases to Mount Vernon (the top photo) and then back to Alexandria, Virginia, where Phyllis and I lived then, for lunch (the bottom photo was taken on our front steps, by Marie Johnston). I think it was that afternoon that I escorted Frank and Ollie to an interview at National Public Radio.

The weekend weather was, unfortunately, of the hot and humid East Coast variety that Californians in particular find unbearable. I have an uncomfortable memory of our guests' distressed expressions as Phyllis and I tried to show them a little of our picturesque eighteenth-century neighborhood, Old Town Alexandria, after lunch. We quickly cut the tour short. It was a pleasant visit even so, and when Phyllis and I returned home from work on Monday afternoon, we found flowers on our doorstep, with Frank and Ollie's business cards attached. They're still in my files.

That 1977 visit was the only time I met Woolie Reitherman, at Kennedy Center just before the premiere; I remember he was wearing a resplendent yellow suit. To my disappointment, Woolie never responded to my requests for an interview. I did meet and interview all the other Disney animators known as the "nine old men," though, except for John Lounsbery, who died much too soon. Ollie Johnston was the last of the nine, and so his passing has generated more comment than might have been occasioned just by the very high quality of his animation.

That 1977 visit was the only time I met Woolie Reitherman, at Kennedy Center just before the premiere; I remember he was wearing a resplendent yellow suit. To my disappointment, Woolie never responded to my requests for an interview. I did meet and interview all the other Disney animators known as the "nine old men," though, except for John Lounsbery, who died much too soon. Ollie Johnston was the last of the nine, and so his passing has generated more comment than might have been occasioned just by the very high quality of his animation.

I liked Ollie a great deal. Frank Thomas and Ward Kimball, the other two of the "nine old men" whom I knew fairly well, had a certain edge to their personalities—expressed very differently, although in both cases born of high intelligence and supreme artistic gifts—but I never sensed such an edge in Ollie. He also may not have been quite as brilliant an animator as the other two, but at that olympian level the differences are too small to matter much.

Still: as I've written here more than once before, I'm deeply skeptical of the whole "nine old men" mythology. When Disney animation was at its most vital, the idea of freezing it in a mold determined by nine animators, however good they were, would have seemed ridiculous; and it was. The exaltation of the nine, beginning in the '50s, signified the beginning of a steep decline that culminated in the dead-end Disney features of the '70s, Robin Hood and The Aristocats and, to be sure, The Rescuers. I hope that Ollie's death doesn't have the perverse effect of elevating the reputation of the nine still further and making it that much more difficult for today's animators, especially those at Disney, to produce work that is deeply personal, artistically advanced, and quite unlike anything Ollie and Frank and their colleagues ever did.

I wrote about Frank and Ollie, the 1995 film that surveyed Thomas's and Johnston's careers, four years ago, soon after its release on DVD, and about John Canemaker's Walt Disney's Nine Old Men, which includes biographies of both men, in one of my first postings on this site, in May 2003.

The Schulz Kidnaping

Monte Schulz, Charles M. Schulz's eldest son, has responded favorably to my review of Schulz and Peanuts, David Michaelis's biography of the great cartoonist. I expressed puzzlement in that review as to why Michaelis hadn't mentioned a 1988 attempt to kidnap Schulz's wife Jean. Monte wrote:

I should explain why the kidnaping wasn’t in the book, because it was in the first draft. Apparently Jeannie persuaded David to cut it out, feeling it wasn’t that big a part of Dad’s story, and that David had gotten certain important details wrong. Maybe she also didn’t care to draw attention to something that wasn’t very pleasant. In any case, it vanished from the next draft.

What a peculiar book Schulz and Peanuts is: at once a biography so "authorized" that its writer took out significant material at the request of the subject's widow, but also one so slipshod that members of the family, as well as friends who contributed their memories, have complained vigorously about its many inaccuracies.

Monte Schulz has contributed an essay on Schulz and Peanuts for the next issue of The Comics Journal, No. 290, which will also include a roundtable on the book with experts on the comic strip. Should be interesting reading.

Still More on Coal Black

Has any animated short ever stirred up so much controversy as Bob Clampett's Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs? None comes to mind. You can read Thad Komorowski's contribution to the ongoing debate by going to the Feedback page on Clampett and Coal Black.

Has any animated short ever stirred up so much controversy as Bob Clampett's Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs? None comes to mind. You can read Thad Komorowski's contribution to the ongoing debate by going to the Feedback page on Clampett and Coal Black.

And if you want to get a sense of how complicated this controversy really is, I'd suggest that you click on the frame blowup at the left and watch a five-minute clip from the 1943 all-black Fox (not MGM, as I originally had it) musical Stormy Weather, with an exuberant Cab Calloway and the utterly astounding Nicholas Brothers.

I can't watch Calloway in Stormy Weather without thinking of Coal Black (which was released first), just as I can't listen to some of the pop music from the early '40s by Los Angeles-based black artists without thinking of the cartoon. In Coal Black, Clampett unquestionably tapped into contemporary black culture—but did he go far enough in doing so? Or did he compromise the integrity of his cartoon by using character designs and symbols (dice, gold teeth) that reinforced racial stereotypes? For that matter, did the black performers who obviously inspired so much of the animation conform too closely themselves to the stereotypes they knew were in the minds of their white audiences? Well, who knows.

April 10, 2008:

On Schulz and Peanuts

I finally finished reading David Michaelis's biography of Charles M. Schulz, creator of the great comic strip, and you can read what I thought of it by clicking here. Fair warning: this is one of my grumpy reviews. Not recommended if you insist on starting the day with a smile.

From Nick Cross

He wrote in response to my April 8 posting on my second thoughts about his cartoon The Waif of Persephone:

I just read your review. Thanks for that! I agree with you about the animation paling in comparison to Jim Tyer's. His animation was singular in its brilliance and I could only dream of reaching such heights! As to using Flash...yes, it is an unfortunate compromise that I had to make. Since I animated the whole film myself, quite a few shortcuts had to be made, and the use of Flash was indeed one of them. Thanks again for giving my film another look, and giving such a thorough critique. I really appreciate it!

And I very much appreciate the opportunity to give a Waif another viewing via DVD. As I've told Nick, I'm looking forward to watching what he comes up with in the future.

Briefly...

Brad and Thad: Thad Komorowski wrote in regard to my mention, in an April 8 posting, that Brad Bird will direct his next feature as live action, not animation:

Brad and Thad: Thad Komorowski wrote in regard to my mention, in an April 8 posting, that Brad Bird will direct his next feature as live action, not animation:

I personally wouldn't blame Brad Bird in the least if he went into live-action permanently. In that field, a movie is only as good as the person making it, and in Bird's case, they will most likely be very good. In animation, a film is only as good as the person with the bankroll allows the filmmaker to be (which, in all honesty, is the way it's always been). Ratatouille was not Bird's idea, which is why the quality of the actual animation trumped the deus ex machina-ridden script. I was blown away by The Incredibles when it was in theaters, but when looking at it again, today, I can't believe how stilted the animation is.

What I'm left to wonder is why this move hasn't been given more attention by the various websites and blogs. For many, Bird was the last chance for any revival of the classic studio system in a theatrical environment. That he wants to steer away from that must be too unbearable for people to comprehend.

Thad has a new blog that will continue in the vein of his original Animation I.D. blog, although with a wider range of subject matter than his previous emphasis on identifying the animators of classic Hollywood cartoons scene by scene. Thad's reasons for making the switch from Google to WordPress are particularly interesting, I think, and he has confirmed me in my lack of interest in converting this site into a conventional blog.

Walt and Yma Sumac: Alexander Rannie writes, in regard to the 1947 photo of Walt Disney, the Peruvian singer Yma Sumac, and an unidentified man that I posted on March 15, that he recently wrote to Yma Sumac's assistant, Damon Devine, and received this reply:

That was wonderful of you to send me that image I had never seen! There is a third one and I do have that here in my archives. About this Disney visit, I don't know much. It was when she first got here to the U.S. I don't know who the man is—but he may be the boyfriend of her dancer Cholita Rivera or someone from the Peruvian consulate. The poster [that Walt and Yma are holding up in another picture, posted on March 18] is from a much earlier visit to Peru, when Disney went to hear "the child with the amazing voice." I think he wanted to use her voice in a film back then and her mother said no and was untrusting. As of 2008, it is impossible to get this information from Miss Sumac, as her mind has gone in only the last two months. I am devastated. Thank you for bringing a little light to my day with that photo!

So the man remains unidentified, at least for the moment.

Coal Black: David Germain writes, apropos of Milt Gray's defense of Bob Clampett's Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs:

No doubt you've heard of a website called the Big Cartoon Database. Well, the Coal Black cartoon is listed there with several reviews attached. I think you should read the review by whackyoverkhaki (I wish I knew her real name). I think she makes a good statement.

I agree. Whackyoverkhaki, who identifies herself as "a teenage black girl who has to deal with embarrassing stereotypes and ignorance everyday," says she is "a huge fan of this cartoon for so many reasons," even though she is not an uncritical one. She reserves her strongest condemnation for "contemporary stereotypes depicted on BET and MTV. For me, these are the real minstrel shows." Absolutely correct.

Gabler's Disney: Gary Parker wrote with some thoughts (more favorable than mine) about Neal Gabler's Walt Disney biography, and about an interesting encounter with a lawyer who once worked for Walt. You can read Gary's message on the Disney biographies Feedback page.

April 8, 2008:

Waif Revisited

After I saw Nick Cross' The Waif of Persephone at last September's Ottawa International Animation Festival, I wrote about it in a report on the festival, dismissing the film with a brevity and a harshness that I later regretted. I bought a DVD of the cartoon (available directly from Nick), and I've now watched it several times. I still don't like Waif much, but I think my dislike is a little more sympathetic than it was before.

After I saw Nick Cross' The Waif of Persephone at last September's Ottawa International Animation Festival, I wrote about it in a report on the festival, dismissing the film with a brevity and a harshness that I later regretted. I bought a DVD of the cartoon (available directly from Nick), and I've now watched it several times. I still don't like Waif much, but I think my dislike is a little more sympathetic than it was before.

Nick says in his audio commentary for the DVD that he was inspired by Jim Tyer's animation, which flourished in the old Terrytoons. I love Tyer's animation, too, but I think it's very difficult to emulate successfully, and I don't think Nick passes the test in Waif. What Tyer-like animation requires above all is the illusion of spontaneity and furious energy; there should be the sense that the drawings spilled off the animator's board almost as rapidly as they're being projected on the screen. Absent that spontaneity and energy, what you've got are bad drawings and arbitrary changes of shape. That's mostly what we see in The Waif of Persephone, alongside large patches of Flash whose mechanical quality is totally at war with Tyer's kind of animation.

I can't make sense of the story, either. It doesn't hold together as either an environmental allegory (except maybe one so vague it doesn't have a real point) or an extended joke on the same theme. Nick doesn't clarify matters in his commentary, unfortunately. There's a sort of kitchen-sink quality to the cartoon, as in a very strange, very Fleischeresque moment when Persephone bursts into an archaic-sounding but newly recorded song to the tune of "Mysterious Mose." I wish Waif held more such surprises.

So, is there anything to like about The Waif of Persephone? Actually, yes. There are some mildly funny bits, like a parody of 1930s cartoons at the start, but what I liked most were the hints of artistic ambition—in the film's length, its fundamentally serious subject matter, the adoption of Tyer as an unconventional model, and the occasionally clever staging (as in a sequence, made up of still drawings, that nicely captures the tedium of waiting).

I was reminded, in watching Waif, of how rare artistic ambition is in today's Hollywood cartoons. The greatest practitioners in most art forms, be they novelists or painters or playwrights or composers, have always admired and respected their predecessors' work; but they've also wanted to make something just as good, or preferably better. It's hard today to find a trace of such ambition even in those cartoons made by people who take themselves seriously as artists and have a grasp of their medium's history. When I roam through animators' blogs, what I see in too many cases is that hero worship—swooning at the tomb of Chuck or Walt or Bob or some lesser deity—has supplanted the hope of real accomplishment.

There is one exception in this generally somber picture, one cartoon maker who has combined an awareness of animation's history with an unmistakable desire to add something important to it. That person is, of course, Brad Bird. He'll soon be directing his fourth feature, 1906—not as animation, though, but in live action.

Maybe there's a message there someplace.