"What's New" Archives: October 2007

October 29, 2007:

October 26, 2007:

October 25, 2007:

October 23, 2007:

More on Joe Penner and The Drunkard

October 22, 2007:

October 21, 2007:

October 19, 2007:

Keith Scott on Joe Penner and The Drunkard

October 18, 2007:

Charles Schulz's Sad Afterlife

October 16, 2007:

Mysteries on the Way to Solution

October 15, 2007:

October 12, 2007:

October 11, 2007:

October 29, 2007:

Carl Stalling

From Funnyworld's vaults—and in anticipation of the release tomorrow of the fifth Looney Tunes DVD set—I'm reprinting the interview with Carl Stalling from No. 13 (1971). As the only significant interview with Stalling about his vitally important work on the Warner and Disney cartoons, this is probably the most-quoted and most-reprinted item from the magazine. It's actually a synthesis of two interviews recorded in 1969, supplemented with a lot of correspondence between me and Carl.

Carl was old (77) and frail when Milt Gray and I visited him in June 1969, the only time I met him. I remember he was puzzled and a little skeptical about the very idea of an interview. But after Funnyworld No. 13 was published, he was delighted with the result, and with the favorable comments he got from friends and admirers. He died in December 1972.

Thanks again to Didier Ghez, proprietor of the Disney History blog and maestro of the Walt's People series of interview collections, for his scan of the interview.

October 26, 2007:

A Belated Legend

The Walt Disney Company has for twenty years honored select employees as "Disney Legends" at an annual ceremony on the lot. There's a bronze award for each "legend," and those present leave their handprints in fresh cement outside the studio's theater. The number of "legends" has grown to more than 200.

The Walt Disney Company has for twenty years honored select employees as "Disney Legends" at an annual ceremony on the lot. There's a bronze award for each "legend," and those present leave their handprints in fresh cement outside the studio's theater. The number of "legends" has grown to more than 200.

I happened to be on the lot, doing research at the Disney Archives, on the day of the 1992 ceremony. Joe Grant, Jack Hannah, and Winston Hibler were among those inducted by a visibly impatient Michael Eisner, but the honoree I remember is Annette Funicello. She had revealed only months before that she was suffering from multiple sclerosis, and she was already on crutches, a sad and gallant sight among so many inductees who were much older than she.

This year's inductees, at the ceremony on October 10, included such worthy choices as Floyd Norman, the veteran story man, and Dave Smith, the studio's archivist, but one choice shocked me: Dick Huemer. I had assumed that Dick had been designated a "legend" many years before. He was one of Disney's mainstays in the '30s and '40s, as animator, director, and story man; he was Joe Grant's writing partner on Fantasia, Dumbo, the "Baby Weems" segment of The Reluctant Dragon, and such memorable wartime shorts as Education for Death. He wrote many of the best Disney TV shows of the '50s. And he was, besides, a true pioneer who worked for Raoul Barre in the teens and was the Fleischers' best animator in the '20s. (His caricatures of Max and Dave—beautifully rendered in pen and ink—hang in my office.)

I met Dick and interviewed him for the first time in 1973, and we were in touch frequently after that, especially when he began writing a column for Funnyworld called "Huemeresque." He died on November 30, 1979, at the age of 81. Of the hundreds of veterans of the "golden age" whom I met while I was doing research for Hollywood Cartoons, Dick is one of those I remember most fondly, alongside Carl Barks, Wilfred Jackson, Rudy Ising, Bob Clampett, and Phil Monroe, to mention a few others who come immediately to mind. After he died, I had several wonderful visits with his widow, Polly, too.

To honor Dick's memory, I've added a couple of his delightful "Huemeresque" columns to the "Funnyworld Revisited" section of the site. His column on Ted Sears is at this link, and his account of a wartime trip to Washington to sell The New Spirit to the Secretary of the Treasury is at this one. Dick wrote as he spoke, with sly, ironic, self-deprecating wit. He was a real New Yorker, a sophisticate compared with many of his colleagues, but he never took himself, or most of them, too seriously. The crucial exception was, of course, Walt Disney, whom he took very seriously indeed.

Many thanks to Didier Ghez for scanning these columns for me; both have been reprinted in Volume 4 of his invaluable Walt's People series of interview collections. To read more about Dick and other Huemers, visit this family site, which includes a report on this year's "Disney Legends" ceremony by Dick's son, Richard P. Huemer, M.D., who accepted the award for him.

Links

You should be checking on these sites daily through RSS feeds, but in case you're not, let me recommend:

° The wonderful photo of Fred Moore, his wife, and daughter at Jenny Lerew's Blackwing Diaries.

° Joe Campana's extraordinary feats of research at Animation - Who and Where. It's thanks to Joe, for example, that we now know that Moore and Tex Avery were next-door neighbors.

° The concluding installments of Mark Mayerson's monumental examination of Pinocchio through frame-grab mosaics and sophisticated commentary.

° The steady flow of drafts and other historical Disney documents at Hans Perk's site.

° The extraordinary recreations, via frame grabs and Photoshop, of (mostly) Disney background paintings at two different sites, Bob Richards' Animation Backgrounds and Hans Bacher's Animation-Treasures (actually two sites now).

° For general film subjects, David Bordwell's incredibly rich site. See, for example, his recent piece on filmmakers' efforts, starting with D. W. Griffith, to shape what critics (and eventually historians) say about their work. Plenty of people in animation have tried to do the same, of course, whether as slickly as Chuck Jones or as crudely as Ralph Bakshi, but they're all rubes compared with the big-time operators Bordwell discusses.

October 25, 2007:

More on Walt and Zorro

I came away from writing The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney not glad to be through with it but thinking that I'd like to know more about various phases of Walt's life. As I've continued my research, I've naturally wondered if I might find documents that called into question the accuracy of important passages in my book. That hasn't happened, but in a few cases I've found material that has permitted me to be more accurate, or more specific, about what was unavoidably less specific in the book. That's especially true of Walt's activities in the early '50s, when he was wrapped up in the planning for the Disneyland park and a Zorro TV show, and he was pursuing both projects outside Walt Disney Productions.

I've written about that period before, in my posting last June 19 and in an extensive note on my page devoted to corrections and clarifications for The Animated Man. (Most of those corrections and clarifications will be incorporated in the paperback edition—whose price at amazon.com has dropped to $16.71—when it's published in February.) When I was at the Library of Congress last month, I reviewed a lot of copyright assignments involving Disney films—most of them assignments of rights to Walt personally or to Walt Disney Productions, as with the assignment of rights to The Art Spirit that I wrote about a few days ago. There were quite a few Zorro-related assignments, too, some of them shedding more light on the rather convoluted history of Walt's involvement with that character. I've expanded the section of my corrections page devoted to such matters; you can read it by going to the entry for pages 236-37.

I've also added a little additional information about Harry Reichebach's role at the Colony Theatre to the entry for page 65.

I came away from the LC, as always, with a stack of photocopies, not just of copyright assignments but of trade-paper and newspaper articles, most involving Walt. They'll no doubt give birth to more bits of Disney arcana on this site and elsewhere in the months ahead.

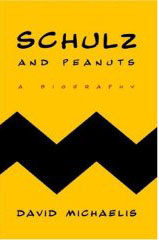

The Schulz Book

Monte Schulz called Tuesday, after we'd exchanged a couple of emails. He had come to my site via a comment in Cartoon Brew's fascinating thread devoted to the family's complaints about Schulz and Peanuts, David Michaelis's biography of Monte's father, Charles Schulz; we talked for well over an hour about that book. With Monte's encouragement, I've ordered Schulz and Peanuts, and I hope to review it within the next few weeks.

Monte Schulz called Tuesday, after we'd exchanged a couple of emails. He had come to my site via a comment in Cartoon Brew's fascinating thread devoted to the family's complaints about Schulz and Peanuts, David Michaelis's biography of Monte's father, Charles Schulz; we talked for well over an hour about that book. With Monte's encouragement, I've ordered Schulz and Peanuts, and I hope to review it within the next few weeks.

Monte and his siblings know that controversy sells books. They have no illusions that their complaints about the inaccuracies in Michaelis's book will discourage sales. Sadly, challenging falsehoods often succeeds only in giving them more currency, at least for a time. To take an all-too-familiar example: If someone says, "Walt Disney was anti-Semitic," and you say, "No, it's not true that he was anti-Semitic," the message some listeners will take away is, "So, Walt Disney was anti-Semitic." The only possible cure is a sustained effort to speak the truth and counter the falsehoods, and I think that's what the Schulzes have in mind.

If I sound as if I've pre-judged Michaelis's book, I have. What I've read in it, and about it, has left me extremely doubtful as to its merits. But I'll modify that judgment as seems appropriate, after I've read it.

Speaking of the Cartoon Brew thread: if you haven't visited it for a while, don't miss today's wonderful posts by Lee Mendelson, as well as the posts from a few days ago by Charles Schulz's daughter Amy and her husband, and a little before that, by Dale Hale, who worked with Schulz on the Peanuts comic books. The portrait of Schulz that has emerged from such postings by people who knew him well is compelling, and intensely sympathetic.

On "Shop Talk"

To use a Peanuts adjective, a crabby visitor to the site has offered these (anonymous) thoughts on what I've described as the tendency of animation blogs to stick to innocuous "shop talk":

John K. has nothing to fear because his reputation in Hollywood is so poisoned you'd have to be stupid or fearless to give him money, but the rest of the world's animators have to worry about feeding their spouse and kids on minimum wage drawing stick figures at Nickelodeon. So bloggers really can't say "Jerry Seinfeld was at DreamWorks today and had no idea what the animation process is. He'd fit right in with the heads here." Likewise, I can't go on a tirade publicly of how very, very few students at animation schools know anything about the cartoons and animators of the golden age and are influenced by run-of-the-mill anime. If you ask me, the only way to save this industry is if a competent artist with lots of money (it's a long shot but it could happen) starts a studio putting out work with integrity. Pixar can't really do that when they're exclusively 3-D, to be honest.

What can I say? Awesome post, dude! You really nailed it.

October 23, 2007:

Hawaii, 1939

From Jim Korkis, apropos my October 21 post about Walt's two visits to Hawaii in the '30s (in 1934 and 1939), this photo of Roy, Edna, Lillian, and Walt Disney from the 1939 visit:

The Disneys appear to be on the beach at Waikiki, in Honolulu; I believe that's Diamond Head in the background. I've read somewhere which Honolulu hotel the Disneys favored (the Royal Hawaiian, I think), but I'm sure Jim will answer that question, and others, in a piece he's working up for a company publication on Disney connections to the islands.

More on Walt at DCA

Didier Ghez, proprietor of the estimable Disney History blog, has written there in response to my skeptical posting about the emphasis on Walt Disney's personal history in the planned transformation of the Disney's California Adventure theme park:

I believe that in this specific case Michael is falling into a very common trap: to consider the Walt Disney Company as a living and thinking entity, instead of the sum of its components. The company is only as good as its members: if someone in the publishing department was ill-advised to authorize or sanction Neal Gabler's flawed bio of Walt, I do not believe this should tint Lasseter's artistic choices for DCA. I do not believe either that we can accuse John Lasseter or WDI [of using] Walt as a crutch in this specific case: there are quite a few original ideas that are not directly linked to Walt in those new plans for the park. Finally, using Walt as the unifying theme to salvage a park about California built in California (an absurd initial idea that Lasseter is obviously not responsible for) is probably the most satisfying solution that exists, if we exclude destroying it and rebuilding it from scratch.

Does that mean that no new ideas coming from Disney today are ... cynical or pure exploitation of Walt (one thinks of the conversion of the Disney Gallery at Disneyland into a high-price suite)? No, of course not. But with the new management on board I believe we should see less and less of this and more honest homages to the man.

That's all reasonable enough. I must add, though, that Disney has always been much better at behaving like a single, coordinated operation than some of the other big entertainment companies. I remember, with a shudder, my experience many years ago when Warner Books commissioned me to write and gather illustrations for a big art book about the Warner cartoons, a book similar to The Art of Walt Disney. When I sought help from other parts of Time Warner—to see some of the more obscure Looney Tunes, for example—I was most often greeted as if I were a flatland furriner who deserved nothing more helpful than a blast of buckshot.

On the rare occasions when I've dealt with Disney on a somewhat similar basis, as when I put together the Library of Congress's exhibition on Disney animation, I encountered nothing like the same attitude; everyone seemed to know they were on the same team. One reason for the difference, I'm sure, is that the Disney company grew itself, as opposed to growing through acquisitions. Time Warner was, and remains, a patchwork, but Disney is still much less of one, despite its acquisition of ABC and other such properties in the Eisner years.

And speaking of Jim Korkis, as I was in the previous item: you'll enjoy Jim's short history of the Carthay Circle Theatre (site of Snow White's premiere) that Didier has appended to his comments above.

More on Joe Penner and The Drunkard

The film composer Alexander Rannie writes:

Per your posts regarding "Agony!" and Joe Penner, a production of The Drunkard played in New York for 277 performances (March 10, 1934 to c. November 1934) with a young Eddie Bracken, no less. And as an aside, the 1940 film The Villain Still Pursued Her is based on The Drunkard and boasts a cast including Billy Gilbert, Buster Keaton and Anita Louise.

So, Penner could have seen The Drunkard when his radio show originated from New York, and he could have picked up the line then. Unless, that is, he used the line before The Drunkard began its run—? The questions never stop! Agony!

Blogs and "Shop Talk"

Michael Jones wrote in response to my comments, in my report on the "Blogging Animation" panel at the Ottawa International Animation Festival, about what I saw as the growing tendency of animation blogs to devolve into vehicles for superficial "shop talk," with little or no serious discussion of the medium:

I suspect that animation is not the only place where people trade in shop talk but are overly kind and uncritical of their work environments. It is well known that most large companies screen potential new hires by looking for information they may have posted on the web. Nobody who is still in the working world would do something as crazy as letting themselves be perceived as criticizing an industry in which they desire to be or remain employed. Websites like Google and the Internet Way Back Machine make going "off the air" all but impossible, what with cached copies of web pages from the dawn of time.

In other words, blogs and the internet itself, those supposed vehicles of "democratization" and a free flow of ideas, can easily be turned against both—a point applicable, obviously, not just to animation blogs but to blogs of all kinds. Probably this transformation of the internet into a tool of management and control is much further advanced than most of us realize.

October 22, 2007:

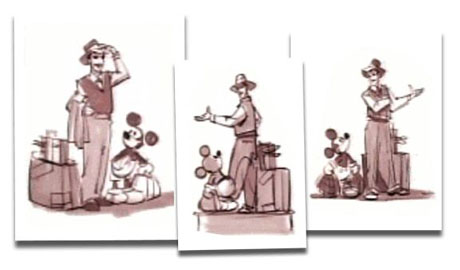

That New "Partners" Statue

Thanks to Michael Jones, a visitor to the site, I finally remembered where I saw the concept drawings for a new "Partners" statue at Disney's California Adventure, one that would show Walt as he arrived in California in 1923. I picked up these drawings from the Disney fan site 2719 Hyperion, Jeff Pepper's exceptionally good-looking and enjoyable blog.

You can also find smaller reproductions of these drawings on Didier Ghez's Disney History blog. Didier has chastised me gently on his blog for my remarks yesterday about the "exploitation" of Walt's memory by the Walt Disney Company, saying in part, "I tend to see the use that is made of Disney history icons and even the new statue of Walt as homages to the man and a great way to introduce new generations to who he was. ... I doubt that cynicism is at work among the imagineers today when it comes to those 'Walt' touches in DCA. From what I know of John Lasseter, he truly respects Walt and Walt's history and is constantly trying to pay tribute to him, directly or indirectly."

I won't dispute Lasseter's sincerity. But I have two problems with the Walt Disney Company's current use of Walt's name and likeness. One is the gap between what appears to be the superficial glorification of Walt's personal history planned for DCA and the careless and condescending treatment his personal history has received elsewhere, especially in Neal Gabler's company-sanctioned biography. My other problem is the obvious use of Walt as a crutch—if you can't come up with anything original, fall back on Walt, his films, his ideas for the parks, his life story. The total effect is, to me, cynical and disrespectful, whatever the motives of individuals involved.

Execution could make all the difference, though. I have to smile at the thought of a resurrected, full-size Carthay Circle Theatre. (There's what is apparently a scaled-down Carthay Circle at Disney-MGM Studios in Florida, but it's a gift shop, not a theater; I haven't seen it.) A revamped DCA that showed real affection and regard for Walt, combined with a light touch...that I could certainly live with.

Walt and The Art Spirit

Some of you have seen a show first broadcast as a Disneyland episode on April 30, 1958, and called "An Adventure in Art." It was from this show that the short called Four Artists Paint One Tree was excerpted and distributed widely to schools, in 16mm.

Some of you have seen a show first broadcast as a Disneyland episode on April 30, 1958, and called "An Adventure in Art." It was from this show that the short called Four Artists Paint One Tree was excerpted and distributed widely to schools, in 16mm.

"An Adventure in Art" is one of those early Disney shows it's impossible to imagine turning up on the schedule a few years later, much less in more recent times. Despite the presence of some questionable clips ("Trees" and "Two Silhouettes" from Make Mine Music), it has real substance. The "four artists" segment is particularly good, because the Disney artists involved—Marc Davis, Eyvind Earle, Josh Meador, Walt Peregoy—are not just lavishly talented but have distinctive points of view. As Walt says in his voiceover, "What each has painted is not just the external appearance of a tree but his own idea of what a tree represents."

Walt himself is more heavily involved than in most of the Disneyland shows; he's on camera at intervals throughout the program and frequently provides voiceovers when he's not seen. The show's premise is that Walt is responding to inquiries from aspiring artists, and in doing so he refers more than once to a book, Robert Henri's The Art Spirit, published in 1923 and still in print today.

Henri (1865-1929) was a leading painter in the "ashcan school" of the early 20th century, and an inspiring teacher. His book is not a systematic treatise, but rather a collection of observations and aphorisms about art assembled by a former student. Many of Henri's ideas have a practical edge that must have appealed to people working in a field like animation, with its many practical demands. A couple of examples:

The eyebrows are hair in the last instance. To a good draftsman they are primarily powerful evidences of the muscular actions of the forehead, which muscular actions are manifestations of the sitter's state of being. The muscles respond instantly to such obvious sensations as surprise, horror, pain, mirth, inquiry, etc., and the muscles are most defined in their effect on that strongly marked line of hair, the eybrow. However subtle the emotion, the eyebrow by its definition marks the response in the muscular movement. ...

The most vital things in the look of a face or a landscape endure only for a moment. Work should be done from memory. The memory is of that vital moment. During that moment there is a correlation of the factors of that look. This correlation does not continue. New arrangements, greater or less, replace them as mood changes. The special order has to be retained in memory—that special look, and that order which was its expression. Memory must hold it. All work done from the subject thereafter must be no more than datagathering.

Walt speaks on the program of reading The Art Spirit himself, and he talks about it in familiar terms. (Reading aloud from the book as he answers what is supposedly an art student's question—"Are silhouettes art?"—he runs his finger along a line of type, exactly the sort of homely gesture it's easy to imagine him making away from the camera.) I was a little skeptical when I heard him cite the book. In reading thousands of pages of documents at the Walt Disney Archives between 1990 and 1997, I never ran across a reference to The Art Spirit, at least nothing substantial enough to be reflected in my notes.

It turns out, though, that Walt thought enough of The Art Spirit to buy it—not just a copy of the book, but the copyright, or at least a large part of it.

I spent four days at the Library of Congress when I was in the Washington, D.C., area last month, and on two of those days I visited the Copyright Office, clearing up some Disney-related questions as well as doing some preliminary research for my next book, on comic books. I discovered in going through the card files that Violet Organ [sic!], executrix of Henri's estate, had executed a copyright assignment for The Art Spirit on January 21, 1957—more than a year, that is, before "An Adventure in Art" aired. The assignment conveys a broad range of movie and publishing rights to Walt Disney Productions, in sweeping language similar to that in other such assignments to WDP (for example, the company bought the right to transform The Art Spirit into "comic strips, picture books, paint books," and the like), but reserves to Henri's estate "the right to publish serialization selections, translations and digests taken from said work as originally published."

The assignment also refers to a contract between the estate and WDP that's not part of the public record. It appears, though, that Disney bought all the rights in the book except the right to publish it in its original form. (There's no indication, in the book's most recent editions or in references to other post-1957 printings, that Disney has ever been mentioned in The Art Spirit itself.)

The details of this transaction, and most likely of Walt's plans for the book, are probably locked away in the Walt Disney Company's "main files," which house documents of continuing legal significance (as opposed to the less sensitive documents housed in the Walt Disney Archives and the Animation Research Library). Did the Disney lawyers think that even so limited a use of The Art Spirit as a few favorable mentions on a TV show required the copyright owner's approval? Maybe; but I'd rather think that Walt had bigger things in mind for Henri's book.

October 21, 2007:

Schulz and Disney

If you've been reading the comments posted at Cartoon Brew, you know that the problems with David Michaelis's biography of Charles Schulz, Schulz and Peanuts, run deeper than just the Schulz children's complaints. So many comments have been posted—more than 130 the last I looked, many of them by compulsive kibitzers and apologists for Michaelis—that it can be difficult to pick out the substantive comments, those by the children and others who knew Schulz personally for decades; but it's worth the effort. There seems to be a growing consensus that Michaelis has simply misrepresented the man.

I think it likely that Michaelis realized late in work on his book that he was writing a story that didn't really have much of a dark side. So, for marketing reasons (and quite possibly with the success of Neal Gabler's Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination in mind), he skewed that story so as to give undue prominence to whatever might make Schulz seem more tormented and melancholy that he really was. I wouldn't be surprised if his editors urged such a change in focus, just as I suspect strongly that the Gabler book's peculiar history (its transformation from a sort of cultural case study into a straight, if twisted, biography) reflects the publisher's thinking as much as or more than the author's. The crassness of big-time publishers knows few bounds these days, and HarperCollins, Michaelis's publisher, is, after all, a Rupert Murdoch property.

As I said in my review of Gabler's book, mistakes are unavoidable in every serious nonfiction book; but the number of the mistakes—and even more, the nature of the mistakes—can be such that an author loses his claim to credibility. I think that's the case with Gabler, and Michaelis's credibility is, to say the least, under severe strain.

Gabler's book didn't enjoy quite the warm critical reception that Michaelis's has received—there was no John Updike review of Walt Disney in The New Yorker, only an incoherent Anthony Lane piece about Walt that used Gabler's biography as a hook—but neither has Gabler's book been criticized for its many errors and distortions as widely as Michaelis's has. Such criticism of Gabler has come only from me and a very few other reviewers, and, more recently, from Walt's daughter, Diane Disney Miller. She wrote to me last week about the controversy over the Schulz biography:

Gabler's book continues to haunt and distress me. I intend to communicate with the family of Charles Schulz to commiserate. What Gabler did to dad is much, much worse than what's been done to Schulz, but I certainly understand the family's feelings of betrayal. I feel betrayed by the company my father founded, that bears his name, and continues to exploit it, but does not care to protect the integrity of it.

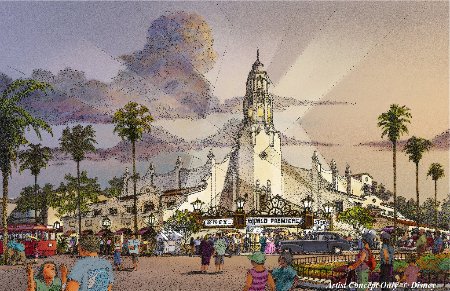

As for that exploitation, consider the coming $1 billion makeover of the Walt Disney Company's failed Anaheim theme park, Disney's California Adventure. The Wall Street Journal reported last Wednesday that the company "hopes to turn the park around by making it more like its successful neighbor [Disneyland], filled with references to company founder Walt Disney. ... California Adventures' new entrance will trace the footsteps of Walt Disney from when he arrived in Los Angeles in the 1920s. ... Similar to Disneyland's iconic castle, the redesigned park will feature a replica of Hollywood's former Carthay Circle theater, where Walt Disney premiered the movie 'Snow White' in 1937 [see the concept art above]."

I've read (I can't locate the source, unfortunately) that a new version of the famous "Partners" statue of Walt and Mickey is in the works for DCA, this one depicting the 21-year-old Walt when he arrived in L.A.

As I write in the Afterword of The Animated Man, "Walt Disney has since his death become a sort of Disney character himself"—thanks, of course, to the company that bears and profits from his name. That process seems to be accelerating, and I shudder to think where it might lead. Perhaps, as with Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, we'll get to choose among different versions of Walt, in plush or bisque or plastic, the "classic" version from the '30s, the "depressed" version from the '40s, the "modern" version from the '50s, or.... Ugh, enough of that! It sounds all too likely.

Walt's Hawaiian Holiday

On October 15, I posted an item about a "mystery photo" of Walt Disney. A day later, thanks to David Lesjak, proprietor of Disney - Toons at War, and Patrick Jenkins, I was able to establish that the photo was taken in Hawaii, and that Walt was in company of an officer from the U.S. Army's Hawaii department. I'm now sure that the photo was taken in August 1934, when Walt and his wife, Lilly, made the first of their two visits to Hawaii in the 1930s (the second, with Roy and Edna Disney, was in 1939).

But exactly when was the photo taken, and what was the occasion? David has now passed along some additional information, from John Patton, a resident of Hawaii's Big Island:

I'm not certain of Walt Disney's public status during the 1930's or his association with the U.S. Army in the Territory of Hawaii, but the military did have several different events that would have drawn in the local community and distinguished guests. The most popular with the soldiers and the local public was the Smokers events at Schofield Barracks Boxing Bowl. There were the annual Horse and Transportation Shows, held also up at Schofield, and then there were the different Unit Organization Day events. All of these events and others brought the military and local communities together to promote good will and the opportunity for the Commanding Officers to show off the spit and polish of their troops. ... By the way, the Hawaiian Department was located at Fort Shafter, and the soldier [in the photo] is a uniformed officer looking much like the Commanding Officer for the Hawaii Separate Coast Artillery Brigade, Brigadier General R. S. Abernethy. He commanded HSCAB from October 5, 1932 to January 18, 1937.

So, if that is General Abernethy, that further clinches the 1934 date. It would be good to know the nature of the event that attracted Walt, most likely as a honored guest. That answer is probably lurking in microfilmed Honolulu newspapers.

October 19, 2007:

Ottawa, Finally

I've pulled together my thoughts on the 2007 Ottawa International Animation Festival, and you can find them at this link.

Keith Scott on Joe Penner and The Drunkard

Keith Scott, the Australian voice artist/voice expert, wrote in response to my recent postings about the radio comedian Joe Penner and his place as the likely source of the Warner cartoon catchphrase, "Agony! Agony!" He has provided some concrete information in the place of some of my rather vague guesses:

I've been following your Joe Penner piece—the use of Penner in the Warner cartoons was because Penner's show was a high-rating success (and very popular with young kids). He did The Baker's Broadcast from New York for two seasons (1933-34 and 1934-35), then took a year off radio before relocating to California for movie work. In 1936 he began a new radio series from Hollywood which ran for four years before his death in January 1941.

His Coast radio show used Mel Blanc and many others who did cartoons in that era, particularly Phil Kramer (who had a featured role with Penner), whom both Avery and Clampett acknowledged hearing on radio and then using him for cartoons.

I dispute [the statement that Blanc was the voice of the duck Goo Goo on Penner's show]. In 1933-34 Blanc—after an unsuccessful short stay in LA—was working in radio in San Francisco and Portland before returning to Hollywood and getting his real start in LA radio at Warner's station KFWB. At the time of the Goo Goo character Penner's show was still out of New York.

Maybe Mel did a duck character in one of the West Coast Penner shows (I have about sixty, but many episodes are still missing). But by the time Penner started in California radio, he was even sending up his "old Joe Penner wanna buy a duck" character, knowing it was dated; in one late 1936 show he had Dave Weber on the show imitating him to his face, but doing the "old Joe."

The Drunkard ran in California for years and was a highly popular after-hours attraction for show folk who loved its florid melodramatic qualities. The villainous Squire was played by character actor Nestor Paiva (used in cartoons by Dick Lundy— the buzzard in the Donald Duck Flying Jalopy, and later by Lantz and Avery—the Mexican in Senor Droopy).

We still don't know how "Agony! Agony!" entered the repertoire of the cameraman Smokey Garner, thence to be adopted by his colleagues at the cartoon studio. Probably from Penner—although we don't know when or how he picked up the line, either. In neither case are we ever likely to have a definitive answer—and the uncertainty is killing me! Agony! Agony!

October 18, 2007:

Charles Schulz's Sad Afterlife

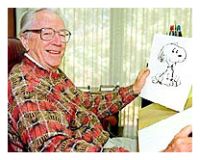

Like many other people, I've been following the ongoing war of words over Schulz and Peanuts, David Michaelis's biography of Charles Schulz.

Like many other people, I've been following the ongoing war of words over Schulz and Peanuts, David Michaelis's biography of Charles Schulz.

On the one side, the book has been praised warmly by reviewers like Bill Watterson (Calvin and Hobbes), in the Wall Street Journal, and John Updike, in The New Yorker. Updike says "there is much to enjoy and admire" in Schulz and Peanuts.

On the other side, Schulz's children have been protesting Michaelis's inaccuracies through comments posted at cartoonbrew.com.

No need to tell you who's winning that war. The last time I checked, Schulz and Peanuts was No. 34 in amazon.com's rankings.

My sympathies are entirely with the Schulz children, and not just because I found Schulz himelf to be an exceptionally open and likable man when I met him almost twenty years ago. I've read very little of Michaelis's book, mainly what's on the HarperCollins Web site, but I found one alarming passage in the review by Updike, who seems in his old age to have become a gullible fuddy-duddy:

Veterans coming home to any midland city found the principal Christian denominations clearly marked: the Episcopalian parish church evoked Anglican tradition in its lavish half-timbering; the Catholic cathedral’s domed basilica proclaimed its place in a universal order; Lutheranism showed its stolid presence in brick churches quietly displaying modest, useful banners announcing bingo and bake sales, their pinnacled bell towers culminating in tall Gothic spires; the Methodist and Presbyterian churches, the one built of stone, the other of wood, each thrust a tall white steeple over opposite corners of a well-tended thoroughfare, invariably Church Street.

Do I need to explain how nonsensical that paragraph is, in its suggestion that Christian denominations in the Midwest adhered rigidly to distinct architectural styles? It's simply a piece of "writing," with only the most tenuous link to reality. The little I've read of the book otherwise suggests that it contains a good deal more of the same. I won't be buying it, or, most likely, reading it, although I'm sure I'll be able to read it for free if I wish. Like other such "painstakingly and thoroughly researched" biographies (Library Journal, naturally) Schulz and Peanuts will be purchased in quantity by my local library system and many others across the country.

Of course, a family's objections to a book shouldn't be taken at face value. What gives weight to the Schulz children's complaints is their specificity. They have accused Michaelis of a broad range of factual errors, and we are promised a further bill of particulars from Monte Schulz. Their focus on such inaccuracies encourages me to take seriously their broader charge, that Michaelis has grossly misrepresented the kind of man Schulz was. (One newspaper headline has already called him "Snoopy's dark master," a probably knowing echo of the title of Marc Eliot's hatchet job on Walt Disney, Hollywood's Dark Prince.)

If Michaelis had been scrupulously accurate, one might say that his interpretation of Schulz's life was, even if wrongheaded, his own business. But mistakes like those that Michaelis is accused of are likely signals that the author was so determined to impose his own ideas on his subject's life that he lost patience with any facts that might get in his way.

Michaelis is a Princeton graduate who has been working and writing in New York for almost thirty years. I see in his conflict with the Schulz family, and in what I've read of his book about Charles Schulz, the same parochialism that crippled Neal Gabler's Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. There's a failure of what I've called imaginative sympathy, a failure that leads too easily, for example, to describing the biographer's subject as melancholy and depressed—a state of mind that many Manhattanites assume is natural for anyone not lucky enough to live there—and that is ultimately condescending. (Poor old Sparky, what a mess. If only they'd had a good shrink out there in the boondocks.)

The same parochialism can be seen at work in the warm critical reception that Schulz and Peanuts has received. There's nothing new in this, or particularly sinister. If you live and write in New York, and you're reviewing the latest book by one of your neighbors, do you want to risk running into him at Barney Greengrass the same Sunday morning you've trashed him in the Times Book Review? Especially if he's a congenial sort. I can think of writers—Stefan Kanfer, author of the worst animation history ever, comes immediately to mind—whose books have probably received their many friendly reviews for just such reasons.

The same parochialism can be seen at work in the warm critical reception that Schulz and Peanuts has received. There's nothing new in this, or particularly sinister. If you live and write in New York, and you're reviewing the latest book by one of your neighbors, do you want to risk running into him at Barney Greengrass the same Sunday morning you've trashed him in the Times Book Review? Especially if he's a congenial sort. I can think of writers—Stefan Kanfer, author of the worst animation history ever, comes immediately to mind—whose books have probably received their many friendly reviews for just such reasons.

Michaelis apparently runs with a somewhat tonier crowd than Neal Gabler does—his acknowledgments and blurbs, available on the Web, are studded with glittering names (including, God help us, Walter Cronkite, Ethel Kennedy, and Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.). His reviews so far have been correspondingly more numerous, more prominent, and more admiring than Gabler's. As an ultimate accolade, there will be a PBS American Masters show on Schulz on October 29, organized around Schulz and Peanuts.

(An American Masters show on Walt Disney, based on Gabler's book, was in the works, too, at one point, but Diane Disney Miller's vehement objections may at least have stalled that project.)

I spoke earlier of the condescension evident in Michaelis's book and in its critical reception. A good part of that condescension is rooted, of course, in the very fact that Schulz, like Walt Disney, was a cartoonist, and a very popular one at that. This is an old story in mainstream publishing; as I've said before, the operative rule, articulated most notably by the cartoonist Jules Feiffer when he was guest editor of an issue of Civilization devoted to the comics, is that those who know very much about the subject are automatically disqualified from writing about it, regardless of their skills as writers. (Feiffer has, of course, contributed a glowing blurb for Michaelis's book.)

What's particularly sad and disturbing in the current circumstances is that the condescension to be expected from Michaelis and his publisher has apparently mutated into cynicism and arrogance. Perhaps turning Charles Schulz and Walt Disney into warped freaks is the only way to sell biographies of them; or maybe that's what publishers think. Same difference.

October 16, 2007:

Mysteries on the Way to Solution

WHERE'S WALT: Thanks to David Lesjak and Patrick Jenkins, we're much closer to knowing when and where that mysterious photo of Walt Disney was taken. As Patrick writes, "The Walt Disney photograph is in Hawaii. The gentleman sitting next to him in the background is wearing the U.S. Army Hawaii department patch on his shoulder. I would say the image is the late 1930s based upon the style of the patch and the hat."

Walt visited Hawaii at least twice in the 1930s, in August 1934 and September 1939. I'd guess, from Walt's still-youthful appearance, that the photo was taken on that earlier visit, but I'll keep trying to pin down the date and the occasion.

THE AGONY OF JOE PENNER: Merlin Haas, who is obviously better at searching the Web than I am, has come up with a script for The Drunkard and a history of that melodrama, which was first produced in the 1840s. As Merlin notes, the crucial phrase—"Agony, agony!"—appears at the end of Act II, Scene 3. W. C. Fields, in The Old Fashioned Way, speaks of ending that scene with a third "agony," but as Merlin says, "Apparently Fields' quip after the curtain was just supposed to show he'd milk a line with an extra 'agony,' given the opportunity."

The question remains how "Agony, agony!" became a catchphrase in the Warner cartoons. Via the cameraman Smokey Garner, definitely, and he probably picked up the phrase from Joe Penner; but did Penner appropriate "Agony, agony!" from The Drunkard? Quite likely; with the end of Prohibition in 1933, The Drunkard was produced on stage in Los Angeles to, as Time put it, "show the comic effects of time." The Drunkard's long run began several months before Penner's first broadcast in October 1933. But did Penner's show, The Bakers' Broadcast,originate from L.A.? If not, was there a parallel production of The Drunkard in New York? So far, my references don't say.

Deeper in the Jungle

I've been thinking more about The Jungle Book, and about why I'm troubled by the enthusiasm that some contemporary Disney animators express not just for aspects of the film—the expertise visible in so much of the animation, in particular—but for The Jungle Book as a whole. The film is, for me, a shaggy, baggy mess, tilted so drastically toward "character" or "personality" that the story all but disintegrates. That anyone should look to it today as a model for their own work seems strange.

I remembered, after my last posting about The Jungle Book, that I'd actually reviewed it twice—not just when it was reissued in 1978, the review I've reprinted here, but also ten years before that, in 1968, when the film was first in theaters. That first review appeared in Funnyworld No. 9, back in the days when the magazine was still a tiny-circulation mimeographed effort (that is, before it became a tiny-circulation printed effort).

I remembered, after my last posting about The Jungle Book, that I'd actually reviewed it twice—not just when it was reissued in 1978, the review I've reprinted here, but also ten years before that, in 1968, when the film was first in theaters. That first review appeared in Funnyworld No. 9, back in the days when the magazine was still a tiny-circulation mimeographed effort (that is, before it became a tiny-circulation printed effort).

When I saw The Jungle Book early in 1968—two or three times, I think, although I remember only the first time, and the date whom I introduced to Disney features—I was older than some of the future Disney animators who were entranced by the film. But I wasn't that old, and I liked The Jungle Book better than I do now, in the Grumpy Old Man phase of my life. In reading my 1968 review, I spotted this point of identification between my real but limited enthusiasm and the full-blooded approval of many younger viewers:

Louie and Baloo strike a nerve—they're archetypes of the kind of adult that children find fascinating, and other adults disapprove. In a word, they're irresponsible. Baloo is nothing if not the Good Uncle, mother's brother who blows in at Christmas loaded with gifts and funny stories and tricks with string. Lovable, but disreputable, and obstinate in his refusal to take life seriously and settle down and get married. Louie is not a relative, and he's not so warm and funny; he may even be a little frightening. A musician maybe, or a circus acrobat, or the best snooker player at the Pastime Pool Hall. It's no wonder that Mowgli finds them more to his liking than he does his guardian, stern Bagheera the panther; the children in the audience probably do, too.

There was, of course, no "probably" about it.

So, let's say you're a ten-year-old who's in love with animation, and you see this movie that stars a couple of characters who are tremendously appealing to you, as a ten-year-old, and who are, besides, animated and drawn with a subtle expertise that you can't begin to understand but that you instinctively recognize and appreciate. That's the way, I'm sure, that The Jungle Book opened doors for any number of aspiring animators. It's such an experience that I hear Brad Bird describing in one of the "extras" for the new Jungle Book DVD set.

If The Jungle Book had affected me that way, I'd love it, too. But would I want to make the same sort of film? That's a different question. Bird certainly hasn't looked to The Jungle Book as inspiration for his features, but I'm not so sure about some of his Disney colleagues. They're the ones whose enthusiasm bothers me a little. It seems too much like the enthusiasm that ten-year-olds felt for The Jungle Book in 1968.

Speaking of the expert animation in The Jungle Book: Michael Sporn offers a dazzling example, some of Milt Kahl's animation drawings for King Louie, at this link.

October 15, 2007:

Where's Walt?

I recently picked up this highly unusual photo of Walt Disney (seen here about twice as large as the print itself) on eBay. The seller had not a clue as to when and where it was taken, and I'm baffled, too, as is Dave Smith, the Disney archivist. Could this be from the South American trip? Is that a foreign military officer next to him? Walt looks a little too young to me for this photo to have been taken in 1941; but maybe it was. Or was it taken a few years earlier at some race track or baseball stadium? Walt was an investor in both. And why is his name at the bottom of the photo (on the negative, apparently)? Can anyone help with the answers?

The Agony of Joe Penner

Mark Kausler has responded to my post last week about the origin of a ubiquitous catchphrase—"Agony! Agony!"—in the Warner Bros. cartoons. John Benson suggested that the phrase entered the cartoons via the nineteenth-century melodrama The Drunkard, as performed in the 1934 W. C. Fields feature The Old Fashioned Way, but Mark has identified an alternative source:

Mark Kausler has responded to my post last week about the origin of a ubiquitous catchphrase—"Agony! Agony!"—in the Warner Bros. cartoons. John Benson suggested that the phrase entered the cartoons via the nineteenth-century melodrama The Drunkard, as performed in the 1934 W. C. Fields feature The Old Fashioned Way, but Mark has identified an alternative source:

It's a Joe Penner saying from his first radio series The Bakers' Broadcast, first heard in 1933. He even worked it into the songs he sang on the show such as "Nobody Knows, Nobody Cares": "I've got woes, you've got woes, woe, ho,ho, agony! My bankbook says I'm no account, my bank lost interest in me!" WB cartoons really kept Joe's comedy alive beyond his untimely death in 1941.

John Benson agrees that

the Penner reference makes sense, because so many of those Warners catchphrases had a source that would have been known to the more savvy members of the audience. But I wouldn't be surprised if Penner got it from The Old Fashioned Way or The Drunkard.

As Mark and John say, Penner does seem to be the likeliest source. I can almost hear Egghead and/or the early Elmer saying "Agony! Agony!" in an imitation-Penner voice as I write, although I can't remember in which cartoon(s). And Penner himself was caricatured in more than one Warner cartoon, the earliest probably being Friz Freleng's My Green Fedora (1935).

Penner is almost wholly forgotten today, but he's an interesting figure, if only because one of his catchphrases, "Wanna buy a duck?" had the wild, short-lived popularity of such later catchphrases as George Gobel's "Well, I'll be a dirty bird" and "Where's the beef?" If you want to get a sense of how popular Penner was in the '30s, even several years after his peak, take a look at Disney's 1938 Silly Symphony Mother Goose Goes Hollywood. It's Penner who brings a bowl when Old King Cole (Hugh Herbert) calls for one, and in the bowl is the duck of his immortal line—Donald, of course.

Penner is almost wholly forgotten today, but he's an interesting figure, if only because one of his catchphrases, "Wanna buy a duck?" had the wild, short-lived popularity of such later catchphrases as George Gobel's "Well, I'll be a dirty bird" and "Where's the beef?" If you want to get a sense of how popular Penner was in the '30s, even several years after his peak, take a look at Disney's 1938 Silly Symphony Mother Goose Goes Hollywood. It's Penner who brings a bowl when Old King Cole (Hugh Herbert) calls for one, and in the bowl is the duck of his immortal line—Donald, of course.

But if Penner was the immediate source of the "agony" catchphrase, where did he get it? Did he, as John Benson suggests, take it from the Fields film or from The Drunkard itself? Is the line present in the actual Drunkard? A Google search wasn't of any help here, to my surprise; I would have thought the script would be online, but I haven't found it. Could Penner have appeared in burlesques of The Drunkard when he was working in vaudeville in the 1920s, before he hit it big in radio? Or did he come up with "Agony! Agony!" on his own?

Presented with such questions, Mark Kausler offers these further thoughts:

It's possible that Joe could have been burlesquing The Drunkard, I don't know if he did it on stage or not (he did a lot of stage work before he appeared in his first Vitaphone shorts). Joe's head writer in the radio days was Henry Rubel, who worked under the name of Hal Raynor. He wrote the line: "Wanna buy a duck?" among others for Penner. So Henry Rubel could have been referencing The Drunkard. I have a few scripts for The Bakers' Broadcast, full of crazy nonsense and puns stretched to the breaking point. It's interesting that Henry Rubel in his capacity as an Episcopalian minister presided at Joe's funeral in 1941!

The first Bakers' Broadcast was October 8, 1933, [nine] months before the Fields film was released [in July 1934], by the way. It's a great loss to radio history that there are only eight Bakers' Broadcast shows that have survived! I would like to hear more of them. I guess we'll have to go to the (gasp) library to read The Drunkard's script. Oh agony, AGONY!

So more research is needed, obviously.

John Benson says of Penner and his catchphrase:

My only direct contact with Penner is the 1934 film College Rhythm, in which Penner's totally unfunny impersonation of a mental defective brought the film to a halt every time he was on screen. (Even worse, the great Lyda Roberti had to pretend that his nauseating laugh so turned her on that she would jump into his arms.) Of course I've always known of him.

One reference that sticks in my mind is that Jack Benny told him to lay off the "Wanna buy a duck" line because people would get tired of it. Penner didn't lay off, and people did get tired of it, and of him. Incidentally, I find that there's a reference to Penner's influence on the Warner cartoons in the Internet Movie Database bio of Penner: "One of the earliest roles of voice talent Mel Blanc on national radio was as the voice of Goo-Goo, the duck that figured in Penner's famous catchphrase. Egghead, the forerunner of the Elmer Fudd character, was partly based on Penner too, which [sic] used a similar voice and mannerisms."

These catchphrases have a long life. One of my favorite lines from The Honeymooners is one Gleason used regularly, "That's a mere bag o' shells." Recently I saw the 1931 film Stepping Out, and there it was: "a mere bag o' shells." I suppose it must have passed through several hands between the film and Gleason, and that film was not the first use.

And here, courtesy of Wikipedia, is another marker of Penner's popularity: a Joe Penner windup toy by Marx. I've read that a good example can sell for as much as $1,500.

The Book Beat

Animated Man Developments

° My Disney biography, The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, will be out in paperback on February 4, 2008. It's available for pre-order at the list price ($18.95) from amazon.com, but amazon's price will no doubt drop considerably before the book is published.

° The Animated Man will be published in Italian next year, by Tunué, a house that specializes in animation- and comics-related titles.

° Most significantly, perhaps, Walt Disney World has ordered almost two hundred copies of The Animated Man, presumably for sale in its stores.

Gabler in Paperback

Neal Gabler's Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination has just been published as a Vintage paperback. I've been very curious whether the paperback would correct a few of the many errors I've cataloged in the book, even if just the mangled names and titles (like giving The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men the title of the earlier Errol Flynn version).

I've been checking, and so far I've found exactly one fix: on page 313, Gabler's description of The Rite of Spring as "a celebration of American Indian rituals" has been changed to "a celebration of pagan Slavonic rituals." As best I can tell, all of the more significant errors and distortions have been left intact. A mainstream reviewer mentioned the Rite of Spring mistake—most of Gabler's mistakes went unnoticed by such reviewers —and that's no doubt why someone at his publisher made the correction.

In case you're wondering, correcting many of the mistakes on my list would have been no big deal—or, more to the point, would have entailed no great expense. Most publishers don't flinch at making corrections that involve no more than a few lines and can be confined to a page; I submitted about two dozen small corrections for the Animated Man paperback. But an author has to care enough about accuracy to make such corrections. My sense after reading Gabler's book in hardcover, with its many sloppy mistakes and occasional invented episodes, was that he really didn't care much about accuracy. The paperback has confirmed me in that opinion.

I'll continue to catalog Gabler's errors as they keep turning up (Spike Jones was a drummer, not a trombonist), but don't look for me to mention his book very often on this page in the future.

Schulz in Jeopardy

Thanks to Mark Evanier and Cartoon Brew, I've been made aware of the controversy surrounding publication next Tuesday of a biography of another great and well-loved cartoonist, Charles Schulz. To judge from advance reports like one in The New York Times, David Michaelis's Schulz and Peanuts depicts Schulz as "depressed, cold and bitter," a much less warm and likable man than the one I interviewed for a couple of hours in 1988.

Thanks to Mark Evanier and Cartoon Brew, I've been made aware of the controversy surrounding publication next Tuesday of a biography of another great and well-loved cartoonist, Charles Schulz. To judge from advance reports like one in The New York Times, David Michaelis's Schulz and Peanuts depicts Schulz as "depressed, cold and bitter," a much less warm and likable man than the one I interviewed for a couple of hours in 1988.

The Schulz family gave Michaelis cooperation that its members now regret. The children in particular reject his characterization of their father, complaining, in effect, that Michaelis twisted the facts of Schulz's life to fit his own agenda and is guilty of many inaccuracies besides. Even so, Schulz and Peanuts has begun to receive glowing reviews, including, remarkably, a long one in today's Wall Street Journal by Bill Watterson, the reclusive creator of Calvin and Hobbes.

It all sounds depressingly familiar.

Walt, Igor, and Stoki

Donald Draganski, who has written to me before about Walt Disney's relations with Igor Stravinsky, adds this sidelight::

I'm in the midst of reading a very interesting book, Stravinsky: The Music Box and the Nightingale by Daniel Albright (Gordon & Breach, 1989). The theme of the book consists in showing how the composer de-personalizes and undermines the distinction between naturalness and artificiality. This is particularly true in his vocal music, in which words are used as building blocks of sound, stripped of their metaphorical meaning.

Anyway, in describing Rite of Spring, the author points out how the early documents indicate that both Stravinsky and [Nicholas] Roerich [Stravinsky's collaborator on the scenario for the ballet and Rite's original stage designer] imagined the men to be dressed in bear skins—half human. (Nijinsky was quoted as saying, "It is really the soul of nature expressed by movement in music. It is the life of stones and the trees. There are no human beings in it.")

Here is the salient passage in the book that I want to call your attention to: "The Rite of Spring, then, concerns the human race before it has become man, before sexual differentiation, when it is still only a provisional manifestation of Nature. Men and women arise laboriously out of the earth, lumpish and half-formed, and at last subside back into it. [...] the Rite depicts the pre-human. It is strange that Stravinsky despised Disney's cartoon of this ballet in Fantasia—Stravinsky called it an 'unresisting imbecility'—for by making the action a minuet of dinosaurs and volcanos, Disney succeeded in eliminating the human presences that were always to some extent an embarrassment to the spectacle." [p. 15]

This leads me to wonder if perhaps Stravinsky's principal gripe was directed against Stokowski, who re-arranged, re-orchestrated and otherwise mangled the score. If the music had remained intact, I can imagine Stravinsky finding the depiction of prehistoric life a viable alternate scenario to the music. Of course, this is pure speculation on my part, but Albright does bring up an interesting point.

Stravinsky didn't mind at all when other conductors performed his works; after all, he knew the value of having his works before the public. He was, however, highly critical and very vocal in finding fault with other people's performances, which is why he devoted so much time and effort to recording all of his works for Columbia, thus creating an aural documentation which would provide future generations with the "right" way to perform them.

Regarding Stokowski, there's a passage in Robert Craft's autobiography (An Improbable Life, Vanderbilt U. Press, 2002) that you'll find interesting: "...afterward, in a restaurant, [in January 1959] Stravinsky introduced me to Stokowski with the remark, 'This is Stokowski, if you want to meet him.' Stravinsky was contemptuous of conductors—'they are not original people'—but his rudeness in this case was unwarranted and extremely embarrassing." [p. 210]

And here, courtesy of Wikipedia, is Roerich's set design (not especially Disney-like) for part one of the ballet:

Agony, Agony!

In the Bob Clampett interview elsewhere on the site, there's this exchange:

Barrier: A standard line you have in your cartoons that I've often wondered about is "Agony, agony!" Is there a particular source for that?

Clampett: Yes, there is. There was a little hillbilly cameraman at the studio named Smokey Garner. He was from the Ozarks, and a real nice little guy who had first worked for Leon at Pacific Art and Title. He was the one who shot, developed and projected our pencil tests for us.

Gray: Oh, that's why there's a Smokey mentioned in your Bugs Bunny cartoon What's Cookin', Doc?, where Bugs says, "Okay, Smokey, roll 'em."Clampett: That's the Smokey. I'd tell him I've got to see that test by three o'clock today, and he'd say, "Oh, agony, agony, agony!"

Ah, but where did Smokey come up with the line? John Benson provided the likely answer after a recent viewing of the W.C. Fields film The Old Fashioned Way (1934): "At the end of one of the scenes while they're performing The Drunkard, one of the player says, 'Agony, agony,' and after the curtain is down he says, 'I left out the third Agony.'"

John wonders "if this is the source of the phrase in the Warners cartoons." No way to know for sure, but my answer would be, probably so.

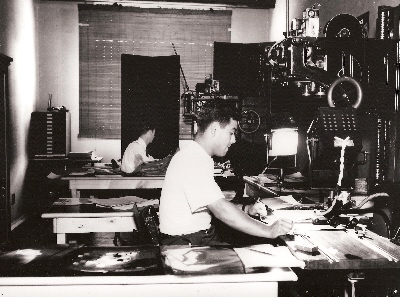

And here's Smokey himself, at work circa 1941 at the Schlesinger studio (this photo was published in the July 1941 issue of International Photographer). The other cameraman, at the rear of the photo, is Manuel Corral.

What Ducks Really Want

At least, on the cover of a Danish comic book. (Thanks to Geoff Blum.)

October 11, 2007:

As I Was Saying...

I'm back from a month-long driving trip to the Washington, D.C., area and Ottawa, and points in between. Catching up on accumulated obligations has taken longer than I expected, and a flood of spam that all but unhinged my computer was no help. I'm still gathering my thoughts about the Ottawa International Animation Festival, but I hope to post them shortly.

Speaking of Ottawa: When I picked up Funnyworld No. 19 the other day—it's the 1978 issue with the Frazetta-style cover, seen in miniature in the frieze at the left—I was reminded that that issue included a four-page report on the second Ottawa festival. That report lamented the '78 festival's failure to live up to the high standard set by the first Ottawa festival in 1976. The writer was an intense, hard-to-please young animator named Michael Sporn...why does that name sound so familiar? Oh, yes...

Sporn at MoMA

I've written here several times about Michael Sporn, who is not just a former Funnyworld contributor but the New York-based proprietor of a must-read animation blog and, above all, a filmmaker of exceptional sensitivity and integrity. (That's a still from his version of Hans Christian Andersen's The Little Match Girl at the right.) Happily, the film curators at the Museum of Modern Art recognize the quality of Michael's work, and MoMA will show more than a dozen of his best films in a retrospective spanning the weekend of November 9-11. There will be three programs, each repeated once. Then, on the evening of Monday, November 12, Michael himself will take the stage with Josh Siegel of MoMA and John Canemaker for a ninety-minute mixture of conversation and film clips. You'll find the details of the complete retrospective at this page on Michael's "Splog" and at this one on MoMA's Web site.

I've written here several times about Michael Sporn, who is not just a former Funnyworld contributor but the New York-based proprietor of a must-read animation blog and, above all, a filmmaker of exceptional sensitivity and integrity. (That's a still from his version of Hans Christian Andersen's The Little Match Girl at the right.) Happily, the film curators at the Museum of Modern Art recognize the quality of Michael's work, and MoMA will show more than a dozen of his best films in a retrospective spanning the weekend of November 9-11. There will be three programs, each repeated once. Then, on the evening of Monday, November 12, Michael himself will take the stage with Josh Siegel of MoMA and John Canemaker for a ninety-minute mixture of conversation and film clips. You'll find the details of the complete retrospective at this page on Michael's "Splog" and at this one on MoMA's Web site.

Phyllis and I will be in New York for a few days in mid-November. We're planning to attend the Monday program (and maybe, if Northwest Airlines cooperates, one or two shows on Sunday afternoon, too). If you're going to be in the New York area, I heartily recommend that you follow our example.

The Jungle Book Revisited

My original reason for pulling Funnyworld No. 19 off the shelf was to re-read the review of Walt Disney's Jungle Book that I published there, soon after that film had its first theatrical reissue in 1978. A new two-DVD set of The Jungle Book was part of the tide of mail, e- and otherwise, that all but submerged me last week, and I was curious what I thought of the film when it was still one of the newer Disney features. I've reprinted my review at this link.

How strange it is to think now about the way things were in 1978. Then, if you wanted to see a Disney animated feature again (and you weren't a high-powered film collector or a friend of one), you had to wait years between reissues. But as much as today's circumstances differ from those of thirty years ago, I found in re-reading my review that subsequent viewings on home video hadn't altered my opinion of The Jungle Book. The film has a lot of ardent admirers, especially among people who were kids when they first saw it (Mary Poppins has admirers of the same kind), but I've never been one of them.

Since I already had The Jungle Book on DVD and laserdisc, I'm not quite sure why I bought the new set ("obsessive-compulsive" is no doubt the operative phrase). The "extras" on such sets are usually my excuse, and the ones I've watched so far are not bad, especially a surprisingly detailed comparison of the Bill Peet version—that is, what Peet had done to the point at which he left the studio—with what eventually wound up on the screen.

Peet's final version would have been more adult than the completed film, I suspect, perhaps a little closer in spirit to the more realistic of Disney's True-Life Adventures, the ones like Jungle Cat, in which every animal is totally focused on killing and eating every other animal. Too dark, Walt Disney said of Peet's work, but the version Walt wound up with is entirely too flabby.

Speaking of adults, what about those grownups who are only now getting around to seeing The Jungle Book? I wonder how many of them echo Bill Benzon, who saw it recently for the first time, on DVD, and complained to me that "there's no soul in this film, no sense that Mowgli was ever in

any real danger. I kept on wondering when Bob and Bing were going to

materialize out of Phil Harris's Baloo. I love some of those road pictures,

but give me the originals, not this tired takeoff."

Speaking of adults, what about those grownups who are only now getting around to seeing The Jungle Book? I wonder how many of them echo Bill Benzon, who saw it recently for the first time, on DVD, and complained to me that "there's no soul in this film, no sense that Mowgli was ever in

any real danger. I kept on wondering when Bob and Bing were going to

materialize out of Phil Harris's Baloo. I love some of those road pictures,

but give me the originals, not this tired takeoff."

Baloo and Bagheera as Bob Hope and Bing Crosby in The Road to the Man-Village...yes, that pretty much fits, unfortunately. And there's no Dorothy Lamour, only a tiresome child wearing an orange loincloth that, as Bill points out, he is utterly unlikely to be wearing, considering that he has never seen another human being.

If you want to read some comments on The Jungle Book, pro and con, from people who work in animation, visit the sites of Michael Sporn (con, with a lot of peppery responses from fans and critics of the film), the animator and director Will Finn (pro), and the storyboard artist Mark Kennedy.

Finn is one of a number of contemporary Disney animators who speak glowingly of The Jungle Book, and of its influence on their own work, in one of the new DVD set's "extras." (Most of those animators were among the many people who saw and loved the film as children.) No one can gainsay the expertise of Jungle Book's animation, or the suavity of the drawing, but the admiring animators seem to see nothing else. I agree with Bill Benzon: "These guys"—Jungle Book's animators—"were running on fumes. All they had going for them was virtuoso technique."

I particularly enjoyed Kennedy's thoughtful essay, which illuminates the baleful influence various unnamed Disney executives exercised over the last few hand-drawn features from that studio. But would the artists making those features—the pathetic Home on the Range comes instantly to mind, since both Finn and Kennedy worked on it, Finn as co-director—have made significantly better films without such interference? I wish could think so; but if The Jungle Book is a director's idea of a good film, how good a film is it reasonable to believe that director is capable of making?