"What's New" Archives: May 2007

May 31, 2007:

Bloghz, Cont'd

The comments keep coming on Michael Sporn's "Splog" in response to his criticism of John Kricfalusi's blog. Well over a hundred comments had been posted by this afternoon, many of them thoughtful and carefully worded. And I should have mentioned the fewer but equally potent comments posted on Cartoon Brew after it linked to the Sporn blog's debate.

Kricfalusi's disciple Stephen Worth has posted many, many comments, in confident, condescending language of the most smug and annoying sort. They gain a great deal in interest, I think, when you set them alongside the stuff that John is currently posting on his blog; you'll want to page down to the May 30 item called "Our Favorite Rapper." "Cognitive dissonance" is perhaps the operative phrase. Or maybe, "American Greetings is calling."

Kricfalusi is a lost cause, and Worth with him. What's most interesting about the flood of comments on the two sites is the debate Sporn ignited when he responded to Kricfalusi's attacks on the modern-design UPA cartoons of the 1950s (one of the most famous of which, Gerald McBoing Boing, I've illustrated here). Probably there hasn't been this much earnest discussion of UPA, its virtues and flaws, since the studio's heyday more than fifty years ago.

As it happens, and as much as I hate to admit it, my own skepticism about UPA is probably closer to the thinking of Kricfalusi and Worth than to that of my longtime friend Michael Sporn. (I am not one of the dozens of the studio's admirers who have been interviewed for what is described as a documentary feature on UPA.) I don't feel the urge to add any comments to the current fire, though. I've already written about UPA, at length, in Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, and I think that what I've written there is more substantial than any of the comments I've read on either Michael's site or Cartoon Brew.

I hope you'll read my UPA chapter, but you certainly don't have to swallow my ideas whole: Amid Amidi's beautifully illustrated book Cartoon Modern offers a well written and much more positive view of the UPA studio. Again, there's more meat in Amid's book than you'll find on the blogs.

Blogs are fine, and the best ones, like Michael Sporn's, stimulate a lot of healthy discussion. They help keep films like the UPA cartoons alive. But even the best blogs are mayflies, barely longer-lived than good barroom debates. Good books last; they're what matters most.

That Sticky Flypaper, Cont'd

Either I forgot to upload the updated page on the flypaper sequence in Playful Pluto or it got lost in the ether. Anyway, it's up now; the new material, on the gag outline, is at the very top of the page.

May 30, 2007:

That Sticky Flypaper

I've added an update to my page devoted to the mysterious sketches for the flypaper sequence in the 1934 Disney cartoon Playful Pluto. I found the gag outline for that cartoon in my files, and it opens up another avenue for speculation about possible authorship of the sketches.

On the Air, Cont'd

To hear my interview yesterday with KPBS in San Diego, click on this link. And to hear much more from me, click here to go to Jesse Ostbaum's interview with me on the MousePod. I haven't listened to either interview yet—I seize on any excuse to avoid listening to myself—but I can say that both interviewers certainly knew what they were doing.

The MousePod also offers an interview with Didier Ghez, proprietor of the excellent Disney History blog and the indefatigable compiler of the monumental Walt's People interview collections. The fifth volume is at the printer; you'll want a copy if you're at all interested in the extraordinary people who created the Disney films and parks.

Bloghz

I can't remember the exact date, but it was about four years ago, sometime in late May 2003, that michaelbarrier.com began operations. I occasionally see my site called a "blog," but it's a blog only in the sense that I usually post stuff on this page every few days. Many of my postings have links to longer, stand-alone pieces on the site—reviews, essays, and the like. The real meat of the site, the stuff I hope has some enduring value, is mostly on those pages. In a true blog, on the other hand, the action is on the home page, where visitors can post comments if they wish, those comments usually appearing on the blog within minutes or hours.

At most blogs, screening appears to be minimal. It's instant response, democracy in action; and a lot of the comments read like something a teenager might have sent as a text message. At my site, by contrast, comments come to me by email, and I feel not the slightest obligation to post them unless they pique my interest. Totally undemocratic? You bet. This is a snobbish, elitist site, a dinosaur in today's internet scheme of things, and I plan to keep it that way. After four years, I don't even expect to do a redesign any time soon (although I do need to fix that out-of-date photo).

I like some blogs a lot—those of Hans Perk, Mark Mayerson, Michael Sporn, and Jenny Lerew come instantly to mind—but their bloggish characteristics are usually subdued, which is to say, the noise level isn't very high and there's lots of material of real substance, like Hans's postings of Disney historical documents and Mark's "thumbnails" for Pinocchio and other Disney cartoons. Most of the comments on their postings are limited in number, and they're actually worth reading.

Michael Sporn devoted his "Splog" a few days ago to criticism of John Kricfalusi's blog. He tends to avoid that blog, Michael wrote, "because I often come away angry. John is one of the most knowledgeable, articulate and intelligent animation writers out there. His 'course' in animation, built on the back of the Preston Blair primer, is priceless. I’ve followed that myself knowing full well that I still have a lot to learn about the medium. However, John likes to taunt the world beyond his little box of fans and followers"—by, for example, dilating on the artistic freedom that Bill Tytla supposedly found when he returned to Terrytoons in 1943, or that everyone supposedly enjoyed at Walter Lantz's studio. Those are, to say the least, unconventional views.

Michael's posting has produced an extraordinary response—around six dozen comments, the last time I looked, many of them strikingly more temperate and civilized than most of the comments that Kricfalusi's own blog stimulates.

I removed Kricfalusi's blog from my RSS feed months ago, and I almost never visit his site now. I got tired of his toy-fascist manner—if anyone disagrees with you, insult them; if they persist in disagreement, repeat the insult in a louder voice—and I resented being lectured about the wonders of The Flintstones and Roger Ramjet and other TV junk that John must have liked when he was a kid. (Beware the person whose taste was perfectly formed by the time he was ten years old.) I can't put any stock in the praise for Kricfalusi from a sycophant like Stephen Worth, who makes his hero sound like animation's answer to L. Ron Hubbard, but perhaps John's postings really are what Michael Sporn and other outsiders have generously called them, a great "course" in the fundamentals of animation. Me, I decided around the time John was cooing over the beautiful backgrounds for Yogi Bear that it was too much trouble trying to find that particular pony under all the manure.

I wonder sometimes why Kricfalusi has turned into such a sad case. One plausible answer immediately suggests itself. John is in his early fifties now; his last TV series, the Ren & Stimpy Adult Party Cartoon of 2003, was a spectacular disaster of the sort that usually renders a filmmaker radioactive; and as best I can tell, he has done almost no work since then, except for the Raku commercials in Flash animation (the absolutely most wonderful, most incredibly fabulous Flash animation ever done, of course; just ask Stephen Worth). I have to think that the perverse nastiness that so dominates John's postings now is at bottom an expression of fear. Certainly, if I were in his position, I'd be very much afraid that I was finished as a director of mainstream animation.

Valuing Walt's Services

As noted in earlier postings, I've continued to add items to my page devoted to the errors and ambiguities in Neal Gabler's Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. More recently, I've revised some items already there—the listing for page 71 in Gabler's book, for example—to incorporate additional information. And I've expanded the listing for pages 589-91 because I think I've solved the mystery I found in those pages.

As noted in earlier postings, I've continued to add items to my page devoted to the errors and ambiguities in Neal Gabler's Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. More recently, I've revised some items already there—the listing for page 71 in Gabler's book, for example—to incorporate additional information. And I've expanded the listing for pages 589-91 because I think I've solved the mystery I found in those pages.

Bob Thomas, in his biography of Roy Disney, Building a Company, describes incidents that he says occurred during a prolonged quarrel between Walt and Roy that culminated in the sale of most of the assets of WED Enterprises, Walt's private company, to Walt Disney Productions in 1964. Gabler, although citing Thomas as his source, places some of the same incidents a few years earlier, during what he describes as a dispute over Walt's 1961 employment contract with the company. I was unsure as to who was right, but now I think the advantage lies decisively with Thomas. He gets some things wrong in both his Disney biographies, but he never comes as perilously close to makin' stuff up as Gabler does.

If I feel the slightest hesitation about accepting Thomas's version, it's only because there's a faint possibility that some of the incidents occurred not in 1960-61 but in 1952-53, when Walt's previous employment contract was negotiated. Walt signed his original contract with the company in 1940, when Walt Disney Productions went public. California law limited employment contracts to seven years, so the first contract ran out in 1947—but Walt and the company didn't agree on a new one until 1953. That contract was succeeded by the one approved by Walt Disney Productions' directors and shareholders (and creditors) in the spring of 1961.

I found a wealth of information about the 1940 and 1953 contracts when I visited the Los Angeles County Superior Court Archives in April and looked at microfilm of the documents filed in connection with a shareholder's lawsuit challenging Walt's 1953 contract. I wasn't able to see those documents before I finished The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney; dealing with the LASC Archive, a dingy subterranean facility, is difficult in person, but it's even worse by mail. (For one thing, cases widely separated in time can have exactly the same case number, the date being the only way to distinguish them—and giving the archivists the correct date is no guarantee that you'll get the correct case file.) Fortunately, my examination of that 1953 case didn't reveal any errors in The Animated Man—but it did suggest some tantalizing avenues for research that conceivably could have led me to expand or rewrite a few passages in the book.

In many important respects, Walt Disney was indistinguishable from the company that bore his name; it was the epitome of the one-man show. But Walt Disney Productions was also a public company, subject to all the constraints of any other public company, and so Walt—who with Roy (and their wives) still owned more than half the company in the early 1950s—was in the eyes of the law a corporate employee whose fundamental relationship with his employer was no different than that of anyone else on the payroll. Valuing Walt's services to Walt Disney Productions would have been unavoidably difficult, even without the additional complications that had arisen by 1953.

Since 1940, Walt Disney Productions had gotten into live-action production in a major way, so that by 1953 Walt had new credibility as a live-action producer. In addition, product licensing, dependent largely on the value of Walt's name, had grown in importance. Walt wanted the new contract to take account of these new realities, by explicitly permitting him to produce live-action films outside the studio and by giving him a license fee for the use of his name.The negotiations for a new contract—between Walt's personal attorney, Lloyd Wright, and lawyers from the Los Angeles law firm O'Melveny and Myers, representing Walt Disney Productions—consumed almost a year, from June 1952 to April 1953. It's from Wright's deposition, in particular, that one gets a sense of how pointed and harsh the discussions sometimes got.

The timing of the contract negotiations is interesting. It was on December 1, 1952—deep into the negotiations, that is—that Walt signed a contract giving him, not Walt Disney Productions, the use of Johnston McCulley's Zorro character. A couple of weeks later, on December 16, 1952, he incorporated his private company, then called Walt Disney, Inc. (the eventual WED Enterprises). Walt did the preliminary planning for Disneyland through that private company, in a "Zorro building" on the Disney lot. It was in the summer of 1953—after everyone had signed off on Walt's new employment contract—that Walt Disney Productions finally began to fall in line behind Walt's ideas for Disneyland. Zorro also became a Walt Disney Productions property, as witness the ABC television series.

Now I'm wondering if the planning for Disneyland by Walt Disney, Inc., was, as we've always been told, nothing more than Walt's way of overcoming the opposition of Walt Disney Productions (mainly Roy Disney) to putting any money into the park. Or was his work on Disneyland, combined with Zorro, Walt's way of telling Roy, as well as the other members of the Disney board of directors, that he just might strike out on his own if the company didn't come up with a contract acceptable to him?

There's no clear answer to such questions in the documents I've seen, but there may be at least part of an answer in another L.A. Superior Court case. The microfilm was unavailable the day I visited, but I've ordered a printout of the case file; if the LASC Archives operates true to form, I may see it sometime late this summer. Perhaps that file will tell us if we narrowly escaped living in an alternative universe in which Walt Disney embarked on a new career as an independent live-action producer in the 1950s, while presiding over a "Disneyland" with no Disney characters in it.

On the Air

I'll be interviewed live around 10:40 a.m. PDT today on KPBS, San Diego.

May 28, 2007:

The Flypaper Sequence Mystery

It's perhaps the most famous sequence in Hollywood animation's history, the flypaper sequence in the 1934 Disney cartoon Playful Pluto. The animation is by Norman Ferguson, but the sequence originated in story sketches by Webb Smith. Those sketches have been lost for decades—or have they? Sketches have surfaced that might be by Smith...or by Ferguson...or by someone else entirely. To see them, and to read about the questions surrounding them, click on this link.

May 24, 2007:

Harry Reichenbach

Above are a couple of portrait photos of Harry Reichenbach that I recently found on eBay. Does his name sound at all familiar? If so, that's probably because you connect him with Walt Disney and Steamboat Willie. Here's how I describe that connection on page 64 of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney:

Harry Reichenbach, best known as a colorful press agent, was in Disney's recollection managing the Colony Theatre on Broadway. He was among the many people in the film industry who saw and liked Steamboat Willie. "He came to me," Disney remembered in 1956, "and he said, 'I want to put that on.' … I said, 'Well, I’m afraid that if I run it somewhere on Broadway that it’ll take the edge off of my selling it and getting the distribution.' … He said, 'These guys don’t know until the public finds out. … Let me have it for two weeks.' … Finally, he said, 'I’ll give you five hundred for two weeks.' And we needed money like what and I said, 'Five hundred a week.' And finally he said, 'O.K., five hundred a week.' They gave me a thousand bucks to run it. And that was the highest price that anybody’s ever paid, up to that time, for a cartoon on Broadway."

However much Reichenbach paid to exhibit Steamboat Willie, it was probably not a thousand dollars. Disney later spoke of receiving half as much: "We didn’t yet have a release for Mickey but Harry [Reichenbach] wanted to book him in the Colony regardless," he said in 1966. "At the time, we were in desperate need of five hundred dollars. To put it briefly, everything owned by Roy and me was mortgaged to the hilt. So I asked Harry for five hundred dollars for exhibiting the first Mickey Mouse one week. I knew that the price was pretty steep. So did Harry. But fortunately for us, he said, 'Let’s compromise. I’ll give you 250 dollars a week—and run the cartoon for two weeks.'"

Reichenbach was a considerable figure in the 1920s, famous for his daring promotional stunts (for a few of them, see the Wikipedia page on Reichenbach). The great comic actor Lee Tracy played a thinly disguised version of Reichenbach in The Half-Naked Truth, a 1932 comedy directed by Gregory La Cava.

When Reichenbach died of cancer in July 1931 at the age of 49, his passing provoked what seems to have been genuine grief, as evidenced by this tribute from Jack Alicoate, editor of Film Daily:

"The great little silver-haired, lovable fighter, who rose from circus boy to the highest-priced press agent in the world, has 'placed' his 'last copy.' He probably knew and called more notables by their first names, both in and out of the motion picture industry, than any man alive."

Among Reichenbach's many pallbearers were such important movie-industry people as Jesse Lasky, Will Hays, R. H. Cochrane, and Al Lichtman. New York Mayor Jimmy Walker was a pallbearer, too.

So what was this high-powered press agent, "everybody's friend," as Alicoate called him, doing managing a Broadway theater, the sort of mundane job you'd think he'd shun? Reichenbach's semi-autobiographical book, Phantom Fame, published the year of his death, says nothing about managing the Colony Theatre (or about Walt Disney), and none of the many other sources I consulted were of any more help.

In writing about Reichenbach's role in bringing Steamboat Willie to the Colony's screen, I used the phrase "in Disney's recollection" deliberately because I wasn't able to find independent confirmation that Reichenbach was in fact the Colony's manager. The many published statements to that effect seem to rely, directly or (more often) indirectly, on what Walt said.

I've learned to trust Walt's memory about most things, and I don't doubt that Harry Reichenbach was involved in some way with the Colony Theatre in the fall of 1928. He handled important promotional campaigns for Universal (the Colony's owner then) as well as the other major film companies. As to whether he was actually the theater's manager—well, that seems unlikely to me, but I'd love to turn up something that confirms just what he did.

In any case, there's no reason to doubt that Reichenbach was instrumental in giving Steamboat Willie a theatrical showcase. If he had not done so, the history of the Disney studio, and of Hollywood animation generally, might have been radically different. So, here's to you, Harry—whatever job you were filling, we're in your debt.

May 19, 2007:

Barks on Campus

As I've mentioned, I wasn't able to see the comic-book exhibit at California State University, Northridge, when I was in Los Angeles last month. Dana Gabbard has made up for that lack by filing this report, complete with abundant links to guides to the CSUN library's holdings of Carl Barks and Chase Craig material, and to a wide-ranging auction of items from Barks's estate. If you want to own the copy of Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book that I gave to Carl and his wife Garé and autographed for them twice, once in 1988 and again in 1989 (because I thought the first inscription lame), now's your chance.

May 16, 2007:

The Book Beat

If you're going to be in downtown Little Rock at noon tomorrow, I'll be speaking at the Central Arkansas Library System's Cox Creative Center at noon, reading some from The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney and taking questions from the audience. Here's the link.

I'll do a phone interview for KPBS (San Diego) on May 29; details later.

Getting attention for the book has been the predictable slog, but sometimes there's praise that's especially gratifying because it comes from people who knew Walt Disney and know much more about his life and work than most reviewers do.

Michael Broggie, author of the beautiful book Walt Disney's Railroad Story and the ultimate authority on Walt's love of trains, posted a five-star rating for The Animated Man on its barnesandnoble.com page. Harrison "Buzz" Price, who was instrumental in choosing the site for Disneyland and helped Walt in many other ways, also liked the book; he told me that he began reading it the day he received it and read it straight through until he finished it the following afternoon, putting it down "only for my 5 p.m. shot over ice yesterday, which was appropriate enough considering the compelling subject." (As you know if you've read The Animated Man, Walt liked to raise a glass.)

May 14, 2007:

Walt at Montréal

"Once Upon a Time...Walt Disney: The Sources of Inspiration for the Disney Studios," the huge exhibition that opened last year in Paris and migrated to Montréal in March, has gotten surprisingly little press in the United States, even at Disney-oriented sites, but Mark Mayerson (who lives in Toronto) has seen it and given it a favorable review on his blog. His concluding paragraph:

"This is the only North American stop for this exhibit and there's nothing like looking at originals. You will know several of the pieces on exhibit here from various books, but the reproductions can't compare to the originals. This is even true for the animation drawings. If you're looking for an excuse to go away for a weekend, it will probably be a while before this much Disney artwork is on display again. Catch it while you can."

I agree heartily with the essential sentiment—if you have even a moderately strong interest in Disney animation, you owe it to yourself to see the show —but I feel some hesitation about Mark's emphasis on "looking at originals." The issue here is similar to the one that arises when we're looking at the original artwork for comic strips, as in "Masters of American Comics," the exhibition shared last year by museums in Los Angeles, Milwaukee, and New York. If an artist intends for his work to be seen in reproduction—or, as with most of the Disney drawings on display, to be absorbed into the artwork that will be seen on the screen—just how much attention should we pay to the "originals" at the expense of the object that the artist himself expected us to be looking at?

I agree heartily with the essential sentiment—if you have even a moderately strong interest in Disney animation, you owe it to yourself to see the show —but I feel some hesitation about Mark's emphasis on "looking at originals." The issue here is similar to the one that arises when we're looking at the original artwork for comic strips, as in "Masters of American Comics," the exhibition shared last year by museums in Los Angeles, Milwaukee, and New York. If an artist intends for his work to be seen in reproduction—or, as with most of the Disney drawings on display, to be absorbed into the artwork that will be seen on the screen—just how much attention should we pay to the "originals" at the expense of the object that the artist himself expected us to be looking at?

Most of the time, I think such Disney "originals" are of greatest value for what they tell us about the thinking that went into the films. They're diminished when we're encouraged to regard them as stand-alone pieces of easel art, as at Montréal, where the drawings and paintings are juxtaposed most often not with film clips but with the third-rate "fine art" that supposedly inspired the Disney artists. I agree with Steve Schneider, who also saw the show in Paris:

"Tracing the studio's inspirations to a raftload of European kitsch not only reaffirms a negative estimation of Disney's accomplishment, it's essentially irrelevant. The studio's greatness was in other realms entirely—in storytelling, characterization, and movement, for starters—and that wasn't even touched upon. Here was a salute that was a facile confirmation of standard preconceptions, not any kind of meaningful celebration. Who this serves is anybody's guess."

Such skepticism is not popular. When some NPR people called me about an interview when the exhibition opened in Montréal, they hastily terminated the conversation when I made clear that I was less than enthusiastic about what the curators had done. But, as I said in my review of the Paris version, you need to see the show even if you suspect you'll wind up sharing my reservations. Here's a link for the basic information. The exhibition catalog is available now in English; I haven't read it yet, but it's a very handsome book that will probably be the exhibition's enduring legacy. You can order it by clicking this link.

Speaking of Mark Mayerson...

...he shares my preoccupation with cartoon acting (although by no means all of my ideas on that subject), and he has put up a couple of interesting posts on his blog that lament the lack of any animated acting equivalent in power to the best live-action performances. Mark singles out Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront, and I'm not sure that's the most fortunate choice; it's been years since I saw that movie, but "heavy-handed" is the phrase that leaps to mind when I think of the film as a whole, if not of Brando's performance. I want to post some thoughts of my own on animated acting in the near future, and Mark's comments will make a great starting point.

T. H. White Gets the Brushoff

Michael Sporn has been posting uncommonly interesting stuff on his "Splog" lately, not least the sometimes sobering accounts of the making of his own films. Would you believe that after getting a well-deserved Oscar nomination in 1984 for Doctor DeSoto, his impeccably charming version of a William Steig story, he could find no work for the next year, except for one commission for a film with a budget of $15,000? Sic transit gloria, to say the least.

Through the good graces of John Canemaker, Michael has also been putting up some Disney storyboards, first for Pinocchio and more recently for The Sword in the Stone. As I've said in a comment on Michael's blog on the Sword boards, the Disney studio bought the screen rights to the story many years before the film was released. The long delay was a source of frustration to T. H. White, who probably hoped that the film would stimulate purchases of his books. He died on January 17, 1964, just three weeks after Sword's release, at the age of 57. I don't know if he saw the film before he died.

Through the good graces of John Canemaker, Michael has also been putting up some Disney storyboards, first for Pinocchio and more recently for The Sword in the Stone. As I've said in a comment on Michael's blog on the Sword boards, the Disney studio bought the screen rights to the story many years before the film was released. The long delay was a source of frustration to T. H. White, who probably hoped that the film would stimulate purchases of his books. He died on January 17, 1964, just three weeks after Sword's release, at the age of 57. I don't know if he saw the film before he died.

White's papers wound up at the Ransom Center at the University of Texas in Austin, which I visited while I was doing research for The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. There's no copy of such a letter in the White papers, but he must have written to Walt to complain about the inaction on Sword in the Stone, because among the papers is this strikingly cool and impersonal reply. It's dated May 7, 1952, and addressed to White in London; it was typewritten by Walt's secretary Dolores Voght on a studio letterhead promoting the reissue of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs:

Dear Mr. White –

I read your recent letter with interest and sympathy for the situation as it affects you. I agree with you entirely in not wanting the property to continue to remain dormant, and that it would be beneficial to all if the story could be developed and become better known.

However, as this matter has to do with a property belonging to our Corporation, it was necessary for me to turn the matter over to my brother, Roy Disney, who has charge of these things. I understand he has written you and suggested that you contact Mr. Cyril James in our London office for further consideration of the matter.

I hope things can be worked out to our mutual satisfaction, and I would like you to know that I am still keenly interested in making a film production from THE SWORD IN THE STONE.

With my regards and all good wishes.

Sincerely,

[signed “Walt Disney”]

May 8, 2007:

Rats!

E. W. Swan points out that a nine-minute preview of Ratatouille, including commentary by Brad Bird, is available now on the Web; you can find it by clicking on this link.

Watching these clips, I'm impressed again, as I was when I saw The Incredibles, by what an excellent director Bird has become. Just look at all that fast action in the kitchen, how clearly staged and timed it is, with none of the phony acrobatics we've learned to accept in this Spielbergian era. As in The Incredibles, the human characters look strange at first, but, for me at least, the strangeness quickly justifies itself: it's as if Bird is announcing that he's not going to use computer animation to achieve the sort of pointless photo-realism that makes Happy Feet so repulsive, but neither is he going to translate hard-drawn cartoon characters into three-dimensional form. Instead, he's going to give us characters uniquely suited to the medium.

Watching these clips, I'm impressed again, as I was when I saw The Incredibles, by what an excellent director Bird has become. Just look at all that fast action in the kitchen, how clearly staged and timed it is, with none of the phony acrobatics we've learned to accept in this Spielbergian era. As in The Incredibles, the human characters look strange at first, but, for me at least, the strangeness quickly justifies itself: it's as if Bird is announcing that he's not going to use computer animation to achieve the sort of pointless photo-realism that makes Happy Feet so repulsive, but neither is he going to translate hard-drawn cartoon characters into three-dimensional form. Instead, he's going to give us characters uniquely suited to the medium.

The fact remains, though, that Ratatouille is a cartoon whose principal character is Remy, a rat—a rat who is more nearly photo-realistic in his appearance (see above) than the human characters that surround him. In close-ups, Remy's human-like characteristics take over, and he seems quite ingratiating. Seen from a distance, he's much more like the real thing. This is not good. Rats are nasty animals, and people are not wrong to recoil from them. To transform so repulsive an animal into a sympathetic character might seem like a director's dream challenge—and surely Bird is up to it, if anyone is—but I can't help but feel that this brilliant director is wasting his time. What's next, a comedy called Snake-Bit, with a cast of rattlers and copperheads? Or maybe a remake of that old Merrie Melodie The Lady in Red, this time with a cast of photo-realistic cucarachas?

I finally got around to seeing Aardman's Flushed Away the other day, and although that computer-animated feature suffers from ailments common to the breed these days—way too much dialogue, synthetic sentiment, an underlying monotony in pacing, overly complicated and correspondingly unbelievable action sequences—it's still an intelligent, often witty film with a surprisingly well-realized female lead. But she's a rat, like most of the other characters (those that aren't amphibians), and even though those rats are more stylized in appearance than Pixar's rat, they still sport long, hairless tails, just as Remy does. It's probably the tails, more than anything else, that are a visual signal to humankind to pick up a broom or a rock or a large stick and get to work when a rat or a mouse shows up. Mickey Mouse's tail has always been depicted as just a black line; here, as so often, Walt knew what he was doing.

The Animation Guild's blog reported the other day that audience interest in Ratatouille ranks far behind interest in other summer movies, and I can't say I'm surprised. But I certainly hope that Brad Bird surprises me, and a lot of other people, by giving us a feature as thrilling as his last one.

May 7, 2007:

Flogging Books in L.A.

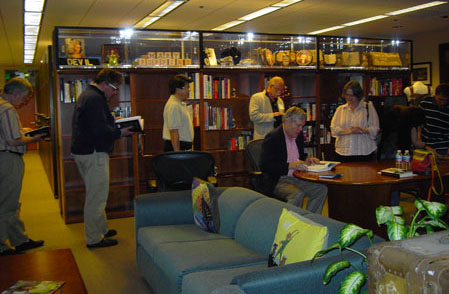

That's me above on the right, signing copies of The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. The signing followed my appearance the morning of April 28 as one of four authors on the panel called "Biography: Icons on the Page" at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books. I shared a signing table with Taylor Branch, a fellow panel member and the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of a trilogy devoted to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and '60s.

The panel was a good one, I thought, but if you have an hour to spare you can judge for yourself by listening to this audio file of the event. Robert Weil, executive editor of the publishing house W.W. Norton, was the moderator. (My panel wasn't televised by C-SPAN, unlike some of the others, but almost all of the Festival events were recorded.) During the signing, I enjoyed the opportunity to visit with old friends like Milt and Katie Gray, Eddie Fitzgerald (proprietor of Uncle Eddie's Theory Corner), and Jerry Beck and Amid Amidi (proprietors of the indispensable Cartoon Brew).

The festival itself, on the UCLA campus, was a remarkable event, a buzzing carnival that reminded me more of the Arkansas Livestock Show of my youth than any literary salon. And, L.A. being L.A., there were the inevitable echoes of more glamorous media: authors congregated in a TV-style "green room" (actually, the UCLA faculty club) before being escorted to the sites of their panels. The festival runs for two days, but after a day of it, Phyllis and I were worn out and happy to retreat to Santa Barbara.

We attended one other panel, "Biography: 20th Century Lives," that Saturday afternoon, because Neal Gabler, the author of Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, was a panelist. I could pick apart Gabler's remarks—how on earth could anyone describe Walt as a "terrible husband"?—but I've already set out at length some of my criticisms of his book, and I heard in what he said at UCLA the same smugness and glib psychologizing I found so disagreeable on the page. There was in his remarks an annoying trace of self-pity, too; no author who is published by a house as rich as Knopf, and who has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, has any business whining about "financial hardship."

I'll continue to add corrections to my Web page, now very long, devoted to errors in Gabler's book. The latest correction, from David Lesjak of the excellent site Disney—Toons at War, is for page 411. I'm sure there will be many more; I'm now reviewing court records and corporate documents that I expect to generate quite a few.

I'm not listing Gabler's errors to be spiteful. The problem is that his publisher's dubious claims, that Walt Disney is "definitive" and "meticulously researched," have been taken all too seriously by reviewers and readers alike, and so Gabler's book is well on its way to becoming the standard Disney biography. There's no way I can accept that status for a book so crowded with distortions and errors, sometimes verging on fabrication. I don't kid myself that many people will pay attention to my lengthening list of corrections, at least in the short term, but someone has to point out that this emperor is very scantily clad.

Coasting

Even setting the festival aside, my week on the Coast was exceptionally busy and interesting. Just after we arrived, I spent a full day in the L.A. Superior Court's archives, an appalling subterranean dungeon, scanning microfilm of the voluminous records of a 1953 Disney case. The next evening Phyllis and I attended a reception thrown by U. of California Press at a dazzling Bel-Air mansion. A greater contrast would be hard to find.

On the Friday before my festival appearance, I taped a video interview for the fifth Looney Tunes DVD set and then made the short hop to the Disney studio for a Q&A and signing session at the Walt Disney Archives' new library. (The photo above is of the signing session, and the library.) The Disney session was great fun. The group was predictably rather small—mine was the first such event in an ambitious new series of historical presentations put together by the archivist Becky Cline—but the questions were all good ones, and I loved meeting people like Hans Perk, whom I've known only through email, and Stacia Martin, whom I've known only through her highly enjoyable featurettes on the Disney True-Life Adventure DVDs. (If you haven't bought those DVDs, perhaps because the films seem too far removed from Walt's triumphs in animation, you're making a mistake.) Some of the attendees had come from other studios, which was enormously flattering. A wonderful occasion, topped off with excellent Thai food when Phyllis and I took Becky to lunch afterward.

That night we attended the Los Angeles Times book awards—Gabler's Walt Disney won for biography—and at the buffet reception afterward happened to share a stand-up table with Leslie Martinson, 92 this year, who let drop that he directed the 1966 Adam West Batman movie, among many other things. Animation, the comics—the associations seem always close at hand.

The rest of the trip had lots of Disney associations, appropriately enough, since The Animated Man doesn't feel "finished" yet and probably won't for a few more months, until I get deeper into work on my next book. On Sunday, at Santa Barbara, I visited the daughter of a former Disney PR man, now deceased, who saved a trove of interesting photos of Walt, and that evening we had dinner in Los Olivos with Fess Parker and his wife, Marcy. The next day I plugged a small but nagging hole in my Disney knowledge by visiting Will Rogers State Historic Park and its polo field.

I couldn't do everything I hoped to do on this trip—I still haven't dined at the Musso and Frank restaurant, one of Walt's Hollywood hangouts, and I couldn't get to the comic-book exhibit at Cal State-Northridge—but it certainly seemed as if we'd done enough by the time we boarded our return flight.