"What's New" Archives: February 2007

February 28, 2007:

The Good Gabler

I've been highly critical of Neal Gabler for the last few months, dismayed by his cold and sloppy biography of Walt Disney, so it's only fair that I call your attention to his stimulating op-ed piece in last Sunday's Los Angeles Times. What a pity he didn't write a book about the Disney organization in the same vein, instead of immersing himself in the life of a man he neither liked nor understood.

Uncle Walt and the Sacred

Bill Benzon, whose thoughts on the animal actors in "The Dance of the Hours" in Fantasia were the basis for a stimulating addition to the site under the Essays tab, has done it again, this time addressing himself to the elements common to Fantasia's opening and closing segments, the Bach Toccata and Fugue and Schubert's Ave Maria. To read what Bill has to say (and my own responses), click here.

Quick Takes

° I liked what Galen Fott wrote in response to my February 27 posting on drafts: "I’ve long questioned how much faith can ultimately be placed in drafts. They’re exceedingly helpful and fascinating, but I’m sure they can be misleading. A rookie animator is stuck on a scene...Freddy Moore comes over and gives him two good drawings that totally make the scene work...but does the draft tell us this? No, the rookie gets total credit for the great animation."

° I didn't identify Larry Latham in my February 25 posting on writing vs. drawing. I was pretty sure which Larry Latham he was, but I wanted to confirm that with him, and now I have. Larry was the director/producer of a couple of direct-to-video American Tail features and some episodes of Disney TV's TaleSpin, among other things. He has been living in Tulsa, Oklahoma, for the last few years.

February 27, 2007:

Drafty, Isn't It?

My February 23 posting, questioning whether there was really an audience for scans of animation drafts and other old documents, produced a limited but intense response. I got a few messages, but there was more activity at Hans Perk's and Michael Sporn's blogs, where a larger number of historical documents have been going up. Not a lot of people care about old drafts, perhaps, but those who care, care a great deal, and they're much more articulate than the run of cartoon fans.

So, I'll keep posting drafts and such—or, more often, interviews, since my store of those is particularly large. My scanning has been crimped lately because I had to buy a new all-in-one printer/scanner/copier in December, and in a fit of shortsightedness I bought one with a letter-size bed, instead of legal-size. Since most of my drafts are legal-size, scanning them will be even more of a pain than before. But I'll try to find some way around that obstacle.

The value of drafts is showing itself at a couple of other sites, Mark Mayerson's and Thad Komorowski's. Mark has been using the drafts Hans Perk has posted, most recently for Pinocchio, as the basis for "mosaics"—pages on which little frame grabs represent each scene, with the animators' names below. Preparing these mosaics is probably even more work for Mark than scanning and posting the drafts is for Hans, but they're marvelous tools. I've been printing them and adding them to the loose-leaf notebooks I've filled with my notes on the cartoons.

I sent Thad a copy of the draft for Disney's World War II version of Chicken Little, and he has posted the cartoon itself on his Animation I.D. site, with the animators' names and occasional other comments superimposed over each scene. As Thad points out, the draft confirms what Milt Gray has always said: Chicken Little in its original version had Foxy Loxy reading Mein Kampf, not a book with the generic title Psychology.

Thad's site is devoted to identifying who animated what in the classic Hollywood cartoons—a tricky business because drafts are so scarce for non-Disney cartoons. For that matter, drafts of all kinds, even "final" Disney drafts, have to be approached with a certain amount of caution; the credits in the Bambi draft are often those of the assistant animators, rather than the animators themselves. But the drafts are usually the best available guide to the animators of particular scenes—and as Thad's comments on Chicken Little suggest, they can be a little humbling even to those who've developed a good eye for animators' styles. The best animators can always surprise us.

February 25, 2007:

More on Writing and Drawing

Larry Latham writes in response to my February 22 posting:

I think the discussion of writing vs. drawing is a bit oversimplified. I don't have any great love or respect for modern cartoon writing, be it for television or features. Features probably work more like the "drawing" examples, but in television, the sheer quantity of product and delivery frequency rule out "drawing" the script on any regular basis. Clampett and the other Golden Age cartoonists had months to produce a six- to seven-minute short. During the most luxurious schedule I ever had in my career, I was putting a new half hour into work every two weeks. We certainly put as much effort as we were capable of into the boarding and preparation of the script, but there was never going to be a time to feel around for gags.

The downside of a script, even a good one, is that you are so tied to it as a structure. Often the clumsiness of certain business or plot points isn't fully visible until you get the script up in pictures, and by then it's usually too late to change anything. Good writers, and there are some, can often come in and help, but all too often they, like cartoonists, tend to fall in love with their own work. The idea of cutting, or worse, changing, an irrelevant piece of dialog or clumsy bit of plotting can lead to major battles that draw energy and resources away from other areas of the cartoon that need them.

I think the ideal would be what you are suggesting: a loose outline with major bits of dialog, followed by a lengthy handout and boarding period. I get the idea that Samurai Jack was done this way, and although the ultimate merits of that show are debatable, the one thing I do admire is how they were able to produce half-hour stories that weren't drowning in clunky dialog and character banter. I think features could learn a lot from them in that regard.

I think the argument is really about the resentment artists feel for the power writers have obtained over the medium, particularly in televison. People who aren't cartoonists—and that certainly includes most executives in charge of production—can't visualize a picture in their heads. I have often found they can't even understand a storyboard. They can understand and respond to a finished cartoon, but prior to that the only familiar format is the script. They may not even understand story structure, but they can point to a line of dialogue and say, "This is funny." This gives them the confidence to move ahead, but rarely to take chances on improving the material.

Because of this need for up-front reassurance, writers have gained a lot of power over the years, often being given producer jobs. Some writers have also been cartoonists, and this is to the good, but all too often they are writers first, meaning they are in love with character banter and puns rather than visual excitement. As always, the better the writer, the less of a problem this is, or at least that has been my experience. At the same time, plenty of people who can draw just take it as a given that they are better suited to cartoons than writers, even though they (the artists) may have no knowledge of all the other elements necessary to make a cartoon—story structure, pacing, and so on.

MB replies: When I read the childish denunciations of cartoon writers that litter some blogs, I can't help but think of the many novels that have summoned up vivid images in my mind. When I first read Tolkien's trilogy, as a teenager, I saw it, in my mind's eye, as an incredible animated film (I'm sure not alone in that). I like to think that if Peter Jackson could have photographed what was inside my head then, the resulting movies would have been much better than the ones he actually made.

Which is only to say that good writing, the kind Larry Latham is talking about, may be potentially as stimulating to artists as good drawings on a storyboard. Given a choice between a Bill Peet storyboard and an exciting script, you'd go with Peet; but that's usually not the choice available. It doesn't seem to me that good ideas have ever been so plentiful at cartoon studios that it makes sense to reject any possible source of them out of hand.

In this connection, don't miss the discussion stimulated by Mark Mayerson's posting headed "The Films I Return to..." The crucial sentence in Mark's short essay: "When I think about animation vs. live action in terms of their effect on me, my conclusion is that the content in animated films is rarely complex enough." Some of his commenters clearly don't want to hear that, but other replies are more to the point: Animation may not be as complex as live action but that's the way we like it. Such is the gist of Peter Emslie's comment, bracing in its frankness:

"Frankly, my interests in animation are pretty much limited to films that have entertaining performances more than complex ideas. If someone were to ask me what I felt was the greatest animated film of all time: the Citizen Kane of animation as it were, I'd likely say Pinocchio. But if pressed to name my favourite animated film of all time, I'd quickly respond with The Jungle Book. While I admire Pinocchio for the technical skill and multi-layered storytelling, it's the good old-fashioned entertainment of fun characterization and musical numbers of The Jungle Book that I viscerally respond to. ...

"I sort of have my doubts about animation as a medium to tackle the same serious issues as live-action does. I think maybe the protagonist of Preston Sturges' Sullivan's Travels came to the same conclusion."

February 23, 2007:

Feeling a Draft

For anyone who cares about the history of Hollywood animation, and Disney animation in particular, Hans Perk's Web site is one of the Internet's shrines. With astonishing frequency, Hans posts rare and illuminating documents from the Disney studio's past, ranging from telephone directories to lecture transcripts. Most often, though, he posts drafts, the scene-by-scene records of who animated what on a particular Disney cartoon.

Right now Hans is posting most of the draft for Pinocchio, following up on Michael Sporn's posting on his "Splog" of the draft for the film's early scenes. Soon, anyone will be able to print a complete copy of that landmark film's draft. I admire Hans tremendously for taking the time and trouble to post so many drafts. Speaking from experience, I can say that scanning such material is a pain, and doing so in quantity is more than a pain.

I love drafts; I add them to my files whenever I can. And yet—I can't shake the feeling that my interest in drafts is shared by very, very few other people. When I posted drafts for Song of the South last year, I expected a flurry of interest, since the animation of that film is so widely (and justly) admired; but there was virtually no response, certainly not enough to make me eager to go through the whole scanning routine again.

So, I have to ask: Should those of us who care about drafts be scanning them and posting them, or should we be seeking out people of kindred mind and exchanging drafts with them? Making copies is a lot easier than making scans, at least for me.

I wonder if we're sinking into a trough—that is, settling into a widespread decline of interest in the history of "golden age" animation, as represented by drafts and similar documents, even while there's continuing interest in kitschy fan stuff, the Mickey Mouse dolls and bedsheets as opposed to the Mickey Mouse cartoons.

Such a trough may be inevitable because so many of the golden age's practitioners have died; we don't have the presence of a Chuck Jones or Ward Kimball or Frank Thomas to stimulate interest in their films and in how they were made. I was startled recently when I realized that it will be 23 years this spring since Bob Clampett died. Bob is as vivid in my memory as if he were alive yesterday, but to many younger people he must seem as remote as, say, Winsor McCay and J. Stuart Blackton seem to me.

More on Those Animal Actors

Thanks to Bill Benzon and Jeff Watson, the Essay page on animated acting in Fantasia has grown a bit. You'll enjoy the new material (and the new pictures), and you'll also enjoy Bill's latest "Dance of the Hours" posting at The Valve.

February 22, 2007:

Writing and Drawing, Cont'd

Those with long memories may recall my January 27 post about writing versus drawing stories for animated cartoons. I gather that this is a boiling question on several noisy blogs that I've given up for Lent. The last time I looked, a few days ago, the only acceptable position for the ideologically committed was that written scripts for cartoons were inherently inadequate, and that cartoon stories could be told only through drawings—by cartoonists, dammit!

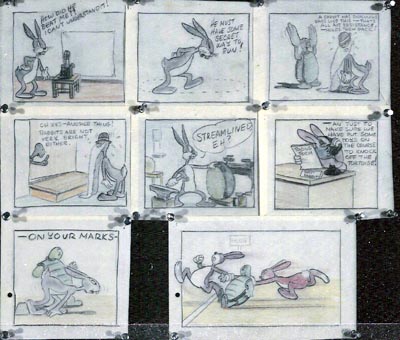

But are there not times, I wonder, when it doesn't make a whole lot of difference how a story is presented? Consider these story sketches for Tortoise Wins by a Hare (1943), directed by Bob Clampett:

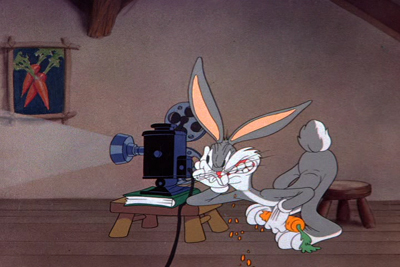

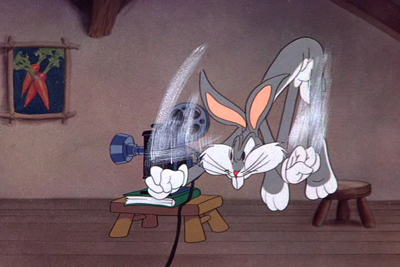

And then take a look at these frame grabs from the general vicinity of the part of the film represented by the first couple of sketches:

I don't see a lot to connect the two, and I certainly don't see anything in the story sketches that's in the least inspirational.

Every cartoon has a different center of gravity. There's a crucial phase that determines largely what the cartoon will be like and how good it will be. In cartoons as different as Friz Freleng's best Looney Tunes and the animated segments of Song of the South, storyboarding was probably the crucial phase. For Chuck Jones's cartoons, the character layouts were most important; in fact, Jones's cartoons are probably the best argument for the idea that "only cartoonists should make cartoons," because Jones did so much "writing" through his layouts.

For Clampett's cartoons, though, it was the director's handout to the animator that mattered most. The story sketches, Tom McKimson's layouts and model sheets—they mattered, I'm sure, but it was because Clampett so vividly acted out what he wanted, and did such things as demonstrating paths of action through what he called "energy sketches," that his cartoons have such tremendous vitality. I doubt the result on the screen would have been a lot different if he had worked with a one-page outline instead of a storyboard.

Another Urban Legend...?

In that same January 27 posting, I mentioned Charles Solomon's claim that One Hundred and One Dalmatians was the first Disney feature to be based on a written script. I meant to respond earlier to that claim, but I got sidetracked. I know of no such script for Dalmatians, only two extensive "story treatments" by Bill Peet, both of which I saw at the Disney Archives more than ten years ago. A 39-page treatment is dated January 27, 1958; an 18-page treatment that covers most of the film is dated April 13, 1959. But Peet (the film's sole writer) also prepared the usual comprehensive storyboards, some of which have been reproduced in various places.

[Addendum: I should have mentioned in my original post that "story treatments" like Peet's for Dalmatians were nothing new. I remember reading a lot of them for Lady and the Tramp, in particular, and I've seen them for other features, too, like Cinderella.]

February 17, 2007:

More Hindemith

Responding to Donald Draganski's piece about Paul Hindemith's visit to the Disney studio, Joshua Wilson offers some informed speculation about how Hindemith might have received Fantasia had he seen it, as he probably didn't. Click here to go to that Feedback page.

Michael Sporn's always enjoyable Splog includes an entry today that was also inspired by Don's article, about Michael's thwarted hopes to translate Hindemith's Four Temperaments into animation. Has anyone ever used Hindemith's music as the basis for an animated film? I can't think of one, although at least a few of his generally rather severe compositions might lend themselves to animated treatment. Symphonische Metamorphosen nach Themen von Carl Maria von Weber, anyone?

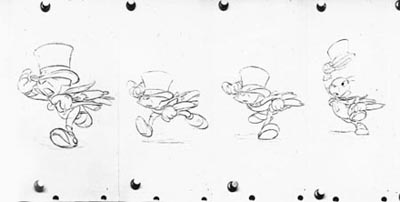

Speaking of Michael Sporn...

...if you haven't looked at the Milt Kahl animation of Jiminy Cricket that he reproduces on his Splog, you should take a look; and you should also read the admiring comments from animation people like Mark Mayerson, Floyd Norman, and Hans Perk. So intelligent, so sensible, and so far removed from the moronic drivel that piles up on so many blogs.

Michael himself comments: "This is a great scene; it uses an economy of drawing while developing character and still moving the film forward. It goes beyond the drawings as all good animation does."

To which I'd add, studying a scene like this is a welcome antidote not just to the limitations of mo-cap and cgi, as some of Michael's commenters suggest, but also to today's common emphasis on the most extreme sort of distortion as the only kind of animation that has emotional validity. Kahl's animation is incredibly intricate and precise, but there's nothing cold about that intricacy; it makes completely visible just how frantic Jiminy is, and just how intensely focused on getting dressed and catching up with Pinocchio as quickly as possible. Despite the limited distortion, there's nothing in the least literal about the way Jiminy moves.

The same sort of attention to detail is visible throughout Pinocchio—often if not invariably adding life to scenes that could otherwise have been a little flat. Years ago, in pre-VCR days, when I was watching Disney films on a Steenbeck editor at the Library of Congress, I made these notes on a scene animated by Woolie Reitherman, the one in which Jiminy does a take upon reading the dove's note that says Geppetto is inside the whale:

"His hat, glasses, and umbrella fly into the air. As umbrella and hat come down, he grabs each with one hand, planting his hat firmly on his head—and then, almost as an afterthought, reaches out with his 'hat hand' and grabs his glasses."

Then I watched the scene again, frame by frame, thanks to that Steenbeck, and corrected myself:

"No, it's much more complicated than that. He first grabs his umbrella with his left hand, then tosses it into the air so that he can grab his hat with his left hand, meanwhile grabbing his glasses with his right hand. He has risen into the air as he does this, and as he comes down he lets go of both hat and glasses, but grabs his hat again as he lands—without looking at it—and then grabs his umbrella, also without looking at it. Then he looks over at his glasses, grabbing them as they fall. All of this takes places in less than 40 frames."

I'm not sure what Jiminy did with his hat, but I'm sure Woolie had that base covered. It's richness of that kind that keeps so many of us coming back to the Disney films of the late 1930s and early 1940s for education and inspiration, even if, as I'm afraid is true in my case with Pinocchio, you find a particular film fatally lacking in some respects.

February 16, 2007:

Hindemith Meets Disney

Some of Walt Disney's meetings with famous classical composers are well known. We've all seen the photos of a smiling Igor Stravinsky in Walt's company during the making of Fantasia, and a 1957 Disneyland TV show, now part of the Disney Treasures DVD set called "Your Host, Walt Disney," recreated Serge Prokofiev's visit to the studio. But Paul Hindemith's 1939 visit is much more obscure.

Donald Draganski, himself a classical composer and performer, contributes to the site a piece based on Hindemith's letters to his wife about his tour of the studio and his impressions of Walt and Leopold Stokowski. If you think that the composer of Mathis Der Maler might not have been a perfect fit with Walt Disney...well, you could be right.

I've known Don Draganski since I was a law student in Chicago and visited him and his wife, Antje, in their northwest Chicago apartment. I remember that occasion particularly well because Don owned the first copy I'd ever seen of Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold, the 1942 comic book that was Carl Barks's debut as "the good artist." Don submitted his Hindemith article for possible publication in Funnyworld, a long time ago, but the magazine expired before I could run it. I'm glad that it was still available all these years later.

As I mentioned, Don is himself a composer, and he is surely the first contributor to my site—or to Funnyworld, for that matter—whose chamber music fills a classical CD from Albany Records, a small but prestigious label. The compositions include "Songs on Mother Goose Rhymes" (for soprano and woodwind quintet), but this is not cartoon music. Neither, I hasten to add, is it "difficult" music. It's just good music, modern but wholly accessible. But don't take my word for it, listen to some samples at Don's own Web site.

February 14, 2007:

Quick Hits

° As a number of Disney-themed sites have noted, the matte artist Peter Ellenshaw has died at Santa Barbara. He was 93. I was generally aware of Ellenshaw's work before I started writing The Animated Man, but it was as I watched all the Disney live-action features made during Walt's lifetime that I came to appreciate his enormous skill. At their best, Ellenshaw's paintings have a matchless storybook quality that elevates even lesser efforts like Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue. They're a vital component of many of the best and most celebrated Disney live-action films, like Third Man of the Mountain and Mary Poppins. I hoped to see Ellenshaw in 2005 during my work on The Animated Man, but his health wouldn't permit a meeting. My loss, for sure.

° John Kricfalusi has marked the first anniversary of his blog with a backhanded acknowledgment of my unintentional role in getting it started, through our exchanges on this site in 2004. (I'm the "male nurse" he mentions but doesn't name; perhaps he has confused me with my cousin Steve, who is in fact a male nurse.) John explains why he abandoned our exchanges: "The guy had the same old tired opinions that had been written in all the previous books on animation ... so I thought, being an actual practitioner of art, story and acting, I might be able to separate all those concepts for him and the few people who might read his blog [sic], so that people could understand the differences between subtle artistic and entertainment concepts. Well, it didn't work. ... I got frustrated and gave up after he just kept repeating the same mantras while not ever answering my arguments. I realized that you can't explain art and entertainment to people who aren't artists or entertainers." Well, that's good to know. And I readily admit that probably no one can ever explain to me the "art and entertainment" in The Ren & Stimpy Adult Cartoon Party.

February 11, 2007:

Fantasia's Animal Actors

[February 13 update: Thanks to Bill Benzon, I've added seven frame grabs to this page. If you haven't visited it yet, you should do so now, since the frame grabs will enhance your appreciation of the points Bill is making.]

[February 13 update: Thanks to Bill Benzon, I've added seven frame grabs to this page. If you haven't visited it yet, you should do so now, since the frame grabs will enhance your appreciation of the points Bill is making.]

Bill Benzon and I have been enjoying a stimulating exchange about the nature of the animated acting in the "Dance of the Hours" segment of Fantasia, and I've shared the results under my Essays tab. This page really cries out for frame grabs, but I'm pressed for time at the moment, so I'll have to save those for later. In any case, if you haven't memorized "The Dance of the Hours," what kind of animation buff are you?

Just Spell My Name Right...

Thanks to Thad Komorowski for letting me know that some of my recent postings have stirred up more dust on Web forums than I would ever have dreamed possible. If you never visit those mysterious online worlds and want to see what you've been missing, click here or here. So now there's going to be a boycott of my site, which, believe me, doesn't have all that many visitors to begin with. In the immortal words of Albert the Alligator, it makes a man humble, and quietly proud. I just hope this boycott gets lots of publicity.

February 10, 2007:

Quick Hits

° Back in 1969 at the Disney studio, when I first interviewed Ward Kimball, he showed me the two-and-a-half-minute film he'd made the previous year, called Escalation, an anti-Vietnam war, anti-LBJ cartoon that makes scatological use of Lyndon Johnson's nose. Now, almost forty years later and almost five years after Ward's death—and at a depressingly similar time in our country's political life—that cartoon has shown up on YouTube, courtesy of the Kimball family and Frank Thomas's son Ted. You can watch it by clicking here. (Thanks to John Canemaker for the alert.)

° Someone questioned my offhand comparison (February 8) of John Kricfalusi with the megalomaniacal dictator of North Korea, Kim Jong Il. In almost all respects, of course, it's a preposterous comparison, as I knew when I made it. So far as we can tell, John K. hasn't starved millions of people to death or tried to develop nuclear weapons. But my comparison wasn't entirely facetious. John can be illuminating when he discusses individual cartoons, but when he talks about animation in broader terms on his blog, he often does so with an unsettling mixture of dogmatism, fervor, and incoherence. That's exactly the combination you'd expect to find when some nut-case tyrant is firing up the masses—and John does indeed fire up his devoted followers, as is all too evident from some of the intemperate comments his postings generate. Come to think of it, maybe Hugo Chavez is a better analogue than Kim. But neither comparison is flattering.

February 9, 2007:

And Now for Something Completely Different...

Thanks to Mark Mayerson for pointing me toward an online auction catalog with excellent pictures of some of the obscure Van Beuren Aesop's Fables dolls I asked about yesterday. Herewith are Mike Monk...

...and the Countess...

...and Puffie Bear...

...and Don Dog.

The names I've used here are those in the 1931 Film Daily article. "Mike Monk" in that article is "Mike the Monkey" on the auction Web site, "Puffie Bear" is "Buddy Bear," and "Don Dog" is "Don the Dog." As to which names are more nearly correct...I know I'm falling down on my job as a universally beloved animation historian, but I don't want to take the time to figure that out.

To go to the auction page from which I borrowed these images, click here. And the auction prices? You can find those here. Prepare to faint/laugh/cringe. Some people must be big Mike Monk fans.

Mark writes: "I have to admit to a strange fascination with the early Van Beuren cartoons. I would never claim that they're any good, but they are weird enough to be entertaining." I agree, in general. The better ones are entertainingly weird; the rest just aren't weird enough.

OK, enough of that. Next time I'll get back to talking about Art and Life and, more interesting than either, Fantasia.

February 8, 2007:

Clampett and Bergen

[Update: Wow, am I embarrassed! There's a five-minute promotional film for the Bergen show, made up mostly of story sketches and with a voice track by Bergen, June Foray, and Paul Frees, on the stupendous Beany and Cecil: The Special Edition DVD released by Image around seven years ago. I spent a lot of time with that DVD when it came out, but I didn't think to check it before posting the item below, with its speculation about such a film, and I didn't remember the Bergen film at all—obviously!]

I like to roam through microfilm of old trade papers—call it a weakness—and I recently ran across a lot of animation-related stories in 1961 issues of Variety. Thanks to The Flintstones, TV animation was hot, and ideas were being floated for lots of shows. I was particularly intrigued by this item in the March 15 issue:

"Don Quinn is coming out of semi-retirement to take on the post of supervising head writer on a new animated cartoon series, 'The Edgar Bergen Show.' Bergen, his wife Frances and daughter Candy form the basis of the characters in the animated stanza but also animated as characters rather than puppets are Charlie McCarthy, Mortimer Snerd and other Bergen creations. [That's Edgar Bergen and Candy, or Candice, Bergen, below, in a 1955 photo.]

"Series, packaged by Bergen and Bruce Kells' new company, Television Arts & Producers Co., is an adult family situation comedy stanza, set in Beverly Hills. Among the wrinkles on the show is the use of 'guest stars,' that is, caricatures of stars like Bob Hope and Jack Benny, who've given their permission for use of their names and caricatures in the show as neighbors of the Bergens.

"Series, packaged by Bergen and Bruce Kells' new company, Television Arts & Producers Co., is an adult family situation comedy stanza, set in Beverly Hills. Among the wrinkles on the show is the use of 'guest stars,' that is, caricatures of stars like Bob Hope and Jack Benny, who've given their permission for use of their names and caricatures in the show as neighbors of the Bergens.

"Cartoons will be produced by the Bob Clampett Organization on the Coast. Clampett, now an indie cartoon house, formerly did the 'Bugs Bunny' shows at Warner Bros. Quinn, Bergen, and Clampett would collaborate on scripts, with Quinn in charge.

"Ells is currently in N.Y. with storyboards and presentations, and reportedly has stirred up considerable interest among agencies. He's also meeting with networks over possible time slots for the stanza."

Clampett mentioned an aborted puppet film with Charlie McCarthy in his interview in Funnyworld No. 12, but I can't remember his ever mentioning this later project, which must not have attracted the interest of sponsors or networks. Presumably there was no pilot, but perhaps there was sample footage of some sort. A perfect YouTube clip, if it exists. If you know anything about this project, raise your hand.

Aha!

I have many reasons for my skepticism about Stephen Worth's increasingly visible Web site, the ASIFA-Hollywood Animation Archive Project. One is that Worth gets so many things wrong, big and small, at that site and elsewhere. He posted (at an online forum) the wacky statement I quoted on February 5, the one about the city of Burbank supposedly insisting, as a condition of a building permit, that Walt Disney design his new studio for easy conversion to a hospital. I considered identifying him by name then but decided against it, since my point was larger than one man's bizarre invention.

As for the small things he gets wrong, here's a recent example: Worth's Archive posting devoted to Clair Weeks's "goodbye book" identifies Clair as Marc Davis's assistant at the Disney studio. Clair was at one point Marc's clean-up assistant, but by the time he left the Disney studio in 1952, he had earned animation screen credit on Peter Pan and on a short, The Little House. He was a full-fledged animator and should have been identified as such. (Milt Gray interviewed Clair for me in 1978, and I met him the next year when he visited friends near my home in Virginia. He promised me an article on his work in Asia for Funnyworld, but, unfortunately, that article did not materialize before the magazine expired.)

Otherwise, the Archive site is simply too full of guff, in the form of incessant self-promotion, pleas for money, extravagant claims (Harman-Ising bar sheets are somehow "the smoking gun," although comparable sheets have been reproduced and explained many times), and, perhaps worst, fawning hero-worship of Spumco's Great Leader, John Kricfalusi, animation's answer to Kim Jong Il. If there is a saving grace amidst all this clatter, it's that some of the stuff Worth scans and posts, like Clair Weeks's "goodbye book," is actually interesting.

Even there, what Worth is doing is hardly unique, although I'm sure he would prefer that you believe that it is (and some gullible folks do, I'm afraid). Hans Perk and Michael Sporn have scanned and posted lots of Disney-related historical items—animation drafts, lecture transcripts, and the like—that are, in my eyes, far more significant than most of the children's books and comic strips that Worth has hoisted up in such quantity ("rat's nest" is the phrase that forces itself on me whenever I visit his site). Other, much quieter sites have made available extraordinary material, like dozens of rare Disney model sheets, that once would have been difficult to find outside the Disney studio. I could even cite the interviews and drafts that I've posted. For that matter, rare old comics are increasingly available on the Web, too.

But here's the catch: I haven't detected a great deal of interest in such material, at my site or others—there's hardly any discussion of it, rarely a request for more of the same. (If you want to stimulate a lot of interest at a Disney-related site, it seems, you need to post gossip about a new ride at Disneyland.) So, if there's any justification for the way Worth runs his site, it has to be that he's trying to generate excitement about items whose value might otherwise not be appreciated. I'm skeptical of such an approach; it reminds me of the compromises that I think severely damaged the Disney show that recently closed in Paris and opens in Montréal next month. Maybe this time taking the low road will work, but I can't say that Worth's record fills me with confidence.

Quick Questions

° Eric Homan writes: "I read your post [February 5] regarding the legend of the Disney studios originally being designed as a hospital fallback. I often heard the same thing about the Hanna-Barbera studio while working there in the 1990s. Maybe it's an urban legend endemic to animation studios?"

I can't think of any other studios that would have made good hospitals. Does anyone out there have any other candidates?

° A trade-paper curiosity: Back in 1931, Film Daily reported that "Aesop's Fables dolls, replicas of the famous cartoon characters," were being given away by theaters to "holders of lucky numbers." There were six dolls: the Countess, Waffles Cat, Don Dog, Mike Monk, Al Fox, and Puffie Bear (you remember all of them well, right?). The paper reported that the dolls "form an extremely attractive and colorful gift and are proving efficient crowd getters wherever the idea has been used."

There must have been a fair number of these dolls made, but I've never heard of any that survived. On the other hand, given how obscure the cartoons and characters are today, possibly the dolls are still around but their cartoon connection has gone unrecognized. Has anyone seen or heard anything about them? I'd love to see a photo of the group.

February 5, 2007:

Truer Than Fiction

Rather to my surprise, I found myself spending quite a lot of time recently watching the new "Walt Disney Legacy Collection " DVD sets devoted to the True-Life Adventures. The DVDs didn't erase my skepticism about the True-Lifes, but they're a lot of fun, for reasons I explain here.

I Can't Get No Stupefaction

Actually, I can. All it takes is trolling through some of the many cartoon-fan message boards. I do so occasionally, and I'm always a little surprised to run across comments from people who actually know what they're talking about, like Jerry Beck and David Gerstein.

Sometimes a posting is so far off the wall that I can only gape at the screen in astonishment. Recently, for example, there was a string on one message board about what was in the Disney studio's "morgue" (the repository of the drawings for completed films). The string somehow wound around to this authoritative-sounding posting:

"When Disney got the financing to build the Burbank studio, the city wouldn't allow a building permit unless the facility was designed as a hospital. The city needed a hospital, and the idea was, if Disney went out of business, at least the city would be able to use the buildings. The animation building had nurse's stations at the end of the hallway, and in the basement was the 'morgue,' which they used to store the finished scene folders of animation. Technically, the morgue evolved into the Animation Research Library, not the Disney Archives. The archives were established separately in the 1960s."

In 1970, not "the 1960s," but forget that. Where on earth did this weird business about the city of Burbank come from? Is it a mutation of the hoary story in which Walt eases his elderly father's worries by telling him that the studio buildings could be converted to a hospital if the studio itself failed? The mind boggles.

It wouldn't matter much, except that such nonsense spreads far more quickly through the Web than it ever did through trashy books, magazines, and newspapers. In a year or two, no doubt, it will be settled wisdom on the message boards that only by placating skeptical city fathers was Disney allowed to build in Burbank.

I guess I'm bothered by such postings because I really do care about getting animation's history right. Unfortunately, from my perspective, that history is for some people nothing more than fuel for idle chatter.

February 2, 2007:

Silly Symphonies

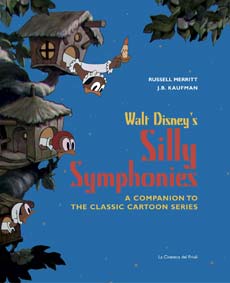

From J. B. Kaufman, the good news that Walt Disney's Silly Symphonies: A Companion to the Classic Cartoon Series, the beautiful book that he co-authored with Russell Merritt, can finally be ordered directly from Indiana University Press. Published last year in Italy (but entirely in English) by La Cineteca del Friuli, Silly Symphonies is not yet available through online booksellers like amazon.com, but presumably will be in the near future.

From J. B. Kaufman, the good news that Walt Disney's Silly Symphonies: A Companion to the Classic Cartoon Series, the beautiful book that he co-authored with Russell Merritt, can finally be ordered directly from Indiana University Press. Published last year in Italy (but entirely in English) by La Cineteca del Friuli, Silly Symphonies is not yet available through online booksellers like amazon.com, but presumably will be in the near future.

The book hardly needs any recommendation to those who are already familiar with Merritt and Kaufman's work, especially Walt in Wonderland, their book on Disney's silent films. I'll have more to say about Silly Symphonies in the near future.