"What's New" Archives: September 2005

September 21, 2005:

MULTIPLE PERSONALITY DISORDER, CONT'D: Milt Gray wrote in response to my postings about casting by character on August 26 and September 1:

"While I fully understand what you are saying, I must admit that although I consider myself an above-average cartoon fan in terms of being knowledgeable and thoughtful about the subject, I do find it difficult to imagine how much better the character animation could be without seeing some examples of it. Are there some scenes that you feel are particularly exemplary of what you are advocating? Maybe I—like so many other cartoon fans—have seen for so many years what has been done that I have just grown to accept that the best that's been done is the best that can be. Or to put it another way, it may be that if the concepts and stories were better, then we as an audience would be less bothered by tiny inconsistencies in character acting.

"In your book, the differences in character acting of Captain Hook that you cite could likely have been overcome not by using a single animator but by discussing the character more in the story stage, to get a more focused idea of exactly who Hook is. Then the animators would have a better defined target to aim for, and the noticeable differences in different scenes would simply not exist.

"Another reason that the differences in Hook's animation don't bother me is that I find in real life that one person will behave quite differently from one day to the next, depending on what mood he is in.

"In live-action movies, tiny details are unavoidable—they are always seen by the camera and shown to the audience, and so having more than one actor playing the same character is unavoidably noticeable. But the mechanics of animation production are such that only broad generalities are possible, and so it is more a matter of how those broad generalities are dealt with that determines how successful a cartoon will be, both artistically and in how it evokes real world realities.

"I have long advocated that the one thing that animation shouldn't even attempt is to re-create the real world. It's just a different medium. The real strength is in the concepts and writing being inspired enough to stimulate an audience, and the purpose of the animation is to explore alternative ways to symbolize or parallel real world realities.

"Ultimately, I think we get back to the discussion we were having a couple years ago, about whether the animators during Walt's time were actually as skilled as some of today's best animators are at drawing and moving the human figure. Walt's animators had the handicap of trying to create a new art form, whereas today's best animators grew up as children absorbing the best of Walt's animators' achievements, and as children practicing illustration drawing (with a passion) and observing human actions, both in real life and in a constant stream of movies on TV. By the time the best of these people became adults, they could draw and animate with skills utterly unknown to the original Disney animators. Most of us today don't notice this advance because the concepts and stories of the Eisner-era films are so poor that we can't relate emotionally to anything on the screen—and on some unconscious level we blame the animators. (After all, it is their work we are watching on the screen.)"

I don't have time, unfortunately, to deal with all the interesting points Milt raises—I'm still hip-deep in my Disney biography, and I will be for a few more weeks—but I do want to respond in general terms.

A question lurking in this discussion is this one: What is a cartoon character anyway; and more specifically, is there any sense in which a cartoon character has an existence apart from the films in which it appears?

Sometimes the answer is yes, but only with those characters so superficially constructed that everything about them can be reduced to formula. Some very good cartoons have been made with such characters, like the best of Jack Kinney's Goofy sports cartoons. To the extent that Goofy exists at all in those cartoons, it's as the sketchiest sort of character, so that to speak of "casting by character" in connection with those films would be to speak nonsense.

Other characters exist largely as roles that different directors (not so much animators) can play in very different ways. Bugs Bunny is less a character than a role, one played brilliantly by Chuck Jones in particular, problematically by Bob Clampett, and not so well by Bob McKimson, when he was directing. Friz Freleng, on the other hand, abdicated too much of the Bugs Bunny role to his layout men and animators; he conceived of Bugs too much in formula terms.

And then there are those characters that simply do not exist, except as a design and maybe the sound of a voice, apart from the work of a particular animator. Dumbo and his mother, in Bill Tytla's animation, are such characters. Tytla's is the kind of animation that I value most: the characters have the unique presence on the screen of live actors, but are themselves inconceivable as live action. I talk so much about casting by character because I think that only rigorous and intelligent casting of that kind can give us animation of such depth.

Captain Hook promises to be an exeptionally rich character in the best of Frank Thomas's scenes, like the seduction of Tinker Bell. I don't see any "broad generalities" in that animation, which is remarkably fluid and subtle in its transitions from frame to frame. But the effect of Thomas's animation is diluted through its juxtaposition with Woolie Reitherman's much broader presentation of Hook. The better the animation, the more such "tiny inconsistencies" are magnified. I don't know how tinkering with the story could have made the two animation styles—and the two different conceptions of Hook—cohere. What should have been sacrificed—Reitherman's gift for broad comedy (he was an leading animator for Kinney's Goofy cartoons) or Thomas's for psychological subtlety? Me, I'd much rather have a Peter Pan in which Hook is less of a clown and more of a menace.

I don't think all animation needs to be as acutely felt as the best of Bill Tytla's, or as delicately probing as the best of Frank Thomas's. But there's no substitute today in what we have in such quantity: highly sophisticated and technically adept animation that is, at bottom, just as much indebted to formulas—and just as superficial—as the animation in Kinney's old Goofy cartoons. The difference being, Kinney knew what he was doing; and he wanted his audience to laugh, and not shed a wholly undeserved tear.

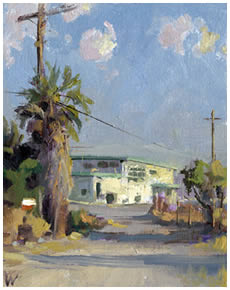

BILL WRAY: A book I've enjoyed dipping into repeatedly is Everyday Life in California: Regional Watercolors, 1930-1950, the catalog of a 2004 exhibit at the California Heritage Museum in Santa Monica. Many of the watercolors are by artists with animation connections of one kind or another—Lee Blair, Art Riley, Millard Sheets, Charles Payzant, Elmer Plummer, Phil Dike—and they're immensely evocative of Southern California as it existed more than a half century ago, in animation's "golden age."

Now

it turns out that a contemporary animator, Bill Wray, is making

paintings of today's California that are very much in that tradition.

He works in oils, and the influences he cites are not the watercolorists

I've mentioned, but he's with them in spirit: "I love the early

2Oth century’s art and architecture," he says on his

Web site, "and work hard to invoke comparisons to that

period in my work. I love the idea of capturing what's left of a

bygone era; recording it before it’s gone, replaced by a new

strip mall."

Now

it turns out that a contemporary animator, Bill Wray, is making

paintings of today's California that are very much in that tradition.

He works in oils, and the influences he cites are not the watercolorists

I've mentioned, but he's with them in spirit: "I love the early

2Oth century’s art and architecture," he says on his

Web site, "and work hard to invoke comparisons to that

period in my work. I love the idea of capturing what's left of a

bygone era; recording it before it’s gone, replaced by a new

strip mall."

Visiting Bill's site is like taking a vacation to a bygone Southern California, one that I find far more congenial than today's traffic-choked megalopolis. Try it, you'll like it.

September 9, 2005:

DUBBED MIYAZAKI: From Joshua Wilson, in response to my comments on Howl's Moving Castle:

"Your analysis of the issues concerning dubbing in

the Miyazaki films seems to be spot-on. I have not seen Howl’s,

but I recently had the opportunity to view both Castle in the

Sky and Spirited Away on DVD. The English dubs on the

trailers alone were enough to put me off from attempting to listen

to the whole movie that way. I had resisted for a long time watching

these films, because the stylized character designs and acting (“doll-like,”

as you put it) seems distracting and a bit wearying to me. After

all, you can just about get the gamut of all the “expressions”

they use in five minutes of any afternoon TV cartoon block these

days. Where I think Miyazaki succeeds (and those horrid TV cartoons

miserably fail) is in allowing these aspects of character to be

an abstraction so as not to distract from the components of the

film that are important. In my judgment, this includes the designs

of creatures, machines, and architecture that make these films so

beautiful and oddly intriguing. In these two films that I have watched

(and enjoyed), Miyazaki is successful in creating an alternate world,

transformed substantially but with nuance. When he maintains a point

of familiar reference, such as Gulliver’s Travels in Castle

in the Sky, it becomes something strange and unfamiliar, mythologized

and ripe for new interpretation. I wonder if much of the stuff is

not just plain weird (as Chihiro herself says in Spirited Away)

only for weirdness’ sake—but still it does capture my

interest, and this despite my skepticism going in."

September 1, 2005:

MULTIPLE PERSONALITY DISORDER, CONT'D: Mark Mayerson writes in response to my August 26 posting:

"I understand your position on animated acting, but I think that all acting is constrained in a way. No performance is pure. Every performance is a mix of the actor and other people on a production. The only question is the degree of the mix.

"Stage actors are stuck with a text and direction that they may not agree with.

"Movie actors are stuck with the same but have additional handicaps. Camera angles have an impact on the significance of each moment. Editors (with or without director input) choose takes and impose pacing. Editing can improve a performance but it might just as well destroy one.

"In animation, the animator is saddled with someone else's voice performance. The voice actor's interpretation is a major constraint on an animator, even if the animator is going to do all of a character's scenes. This is in addition to the same constraints that affect a live action performance on film.

"Finally, there's the issue of rehearsal. On stage, it might last months. Film directors, especially those from the theater or with acting backgrounds, routinely try to get several weeks before shooting. Some live action directors (Hawks and McCarey come to mind) were known for heavily re-working scenes on the set. There is no equivalent in animation. It's too expensive for animators to try different approaches to characters or scenes with the same freedom as live actors. If animators are lucky enough to get months to do test animation, the best they can hope for is to try out a sequence or two.

"For that reason, rehearsal has migrated upstream into the story reel. That's the cost effective place to try variations and see what works. But this means that animators aren't hired to create a performance, but are hired to create a predetermined performance, one which has been shaped by the voice and the story reel.

"I think that animators are up against a much tougher challenge than live actors in film, which may be why animating acting is so often disappointing. However, I'm still not convinced that casting by character is the only way to get a good performance.

"You're on record as liking work by Clampett, Jones and Brad Bird, all of whom are directors who dominate their films and who cast their animators by scene, not by character. Perhaps your disappointment in the films where Thomas and Johnston animated by sequence is not due to their approach so much as it's due to Reitherman being a weak director.

"The quality of an animated performance may have more to do with the relationship between the script, director, voice performance and animator than whether an animator is cast by character or sequence."

It's true that circumstances often conspire to prevent actors—whether they're appearing "live" or working as animators—from performing at their best, but that's not what I was talking about. Let me circle back around to my point by talking about an imaginary production of, let's say, Othello, in which everything (physical facilities, rehearsal time, direction) is ideal. Let's suppose further that Othello is played each evening not by one actor but by two, perhaps Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles (both of whom played the Moor memorably on film). The actors are made up to look as much alike as possible. Moreover, they have agreed on an interpretation of the role, so it's always clear that they're trying to play the character the same way. It's Olivier in one scene, Welles in another, each actor taking those scenes that actor and director agree bring out his strengths. Could all those steps render the differences between the actors irrelevant?

Of course not. Any such production might be intriguing, but we can't help but be aware of even subtle differences between actors, and so Othello would inevitably seem less like one character than two. The same is true in animation, and that's why I speak somewhere in Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age of the sensation that a character's place has been taken by a "not-quite-right double."

It's only through casting by character that the necessary identification between character and animator can be made as strong as possible. Such casting is the more important the more distinctive and original the animators involved, as with some of the early Disney animators, and the more a film's director cares about bringing his characters to life as complex individuals.

When casting by character isn't feasible, for whatever reason, the alternative is for the director to, in effect, play all the parts, by controlling the animators' performances so thoroughly that differences between animators are minimized. That is certainly what happened in the best Jones and Clampett cartoons—in very different ways—and I'm quite sure it's what happened in Bird's Incredibles.

For that matter, it's pretty much what happened in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Walt Disney pioneered casting by character in his mid-thirties cartoons, but he stepped back from it in work on Snow White—it must have seemed impractical, with so many characters involved—and he had to make up for that mistake through the most painstaking scrutiny of the work of his animators.

In most animation, however, the casting problem has been finessed by settling for only a superficial consistency. That happens most obviously in TV stuff (where characters are usually nothing more than forced voices, crude designs, and perhaps a few mannerisms), but the same expedient has been adopted in much more ambitious films.

In Disney's Peter Pan, for instance, Captain Hook looks and sounds much the same from scene to scene, but he is simply not the same character in Frank Thomas's scenes as he is in Woolie Reitherman's. The differences may not be jarring, but they're real; and they exist because Hook was ultimately defined less as a character than as a voice and a design.

When a character is defined that way, as so many are, casting by character can indeed seem like a pointless extravagance. But it's this reliance on the superficial—sanctified by decades of practice and, more recently, by authorities like Thomas and Johnston and Richard Williams—that has drained most animated characters of screen presence and trivialized the films themselves.