INTERVIEWS

| The Bob Clampett unit (and a couple of interlopers) at the Schlesinger cartoon studio, in a photo probably taken in 1942. Phil Monroe is at top left; the others standing are, from left, Melvin "Tubby" Millar, Frank Powers, Virgil Ross, Tom McKimson, Warren Foster, Bill Melendez, Bob Clampett, unidentified, Lou Lilly, Warren Batchelder, Michael Sasanoff (leaning forward), Bob North, and I. Ellis. Kneeling, from left: Harry Barton, Don Christensen, Cornett Wood, Rod Scribner, Earl Klein, and Bob McKimson. As to why Millar and Christensen were in the photo, since they were not in Clampett's unit at the time, Clampett said the photo was not strictly a unit photo; to quote my paraphrase of what he told me in a 1979 phone conversation, "It was a case of guys coming back from lunch and someone saying, 'C'mon, get in the photo.' " Photo courtesy of Bob Clampett. |

Phil Monroe (1976)

An interview by Michael Barrier and Milton Gray

Chuck Jones once told me that Phil Monroe was unusual among animators because he had a sense of humor. He did indeed; he had a wonderful laugh, and I was fortunate to hear it during two different interviews, the first in 1976 and the second in 1987, less than a year before Phil's death. This is the first of those interviews; the second is at this link.

Milt Gray and I interviewed Phil on October 29, 1976, during a two-week trip that took us down the California coast from San Francisco to Los Angeles and to interviews with more than two dozen of Hollywood animation's grand old names, starting with Ben Sharpsteen and ending with Gerry Geronimi. Those interviews were part of the research for my book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. I remember hoping at the time that I would learn enough on that trip that I could finish the book in a few more months. Fat chance; I didn't finish the book for another twenty years, after Milt and I recorded a lot more interviews.

Phil Monroe was working in 1976 for the Leo Burnett advertising agency on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. He had begun his career at Leon Schlesinger's Warner Bros. cartoon studio in 1934, animating for an honor roll of major cartoon directors—Friz Freleng, Frank Tashlin, Chuck Jones, and Bob Clampett—before entering the Army Air Force and working alongside other major talents, including Frank Thomas and John Hubley. After the war, he worked for Warner Bros., twice, and UPA, as well as commercial houses.

I mentioned Phil's laugh; you can hear it on this brief audio clip (mp3 player required), which I pulled for my audio commentary on Bob McKimson's Hillbilly Hare on one of the Looney Tunes Golden Collection DVDs. In it, Phil talks about the square dancing craze that he was instrumental in bringing into the Warner cartoon studio and that was memorialized in the McKimson cartoon.

I mentioned Phil's laugh; you can hear it on this brief audio clip (mp3 player required), which I pulled for my audio commentary on Bob McKimson's Hillbilly Hare on one of the Looney Tunes Golden Collection DVDs. In it, Phil talks about the square dancing craze that he was instrumental in bringing into the Warner cartoon studio and that was memorialized in the McKimson cartoon.

What follows is the complete transcript of the interview, incorporating the mostly minor changes Phil made in 1978. As the interview began, Milt Gray had just mentioned that he had worked at Chuck Jones’s studio as an assistant under Manny Perez.

Monroe: Manny was an old high school buddy of mine. In fact, We started together at Warner Bros., in 1934. I was right out of high school in ‘34; 17 years old, and in order to get my high school diploma, I went to night school and accepted this job at Warner Bros. in June 1934. I met Chuck the first day along with Bob Clampett. I went to night school for several months at Polytechnic night school and got my diploma. I graduated with my regular class, but I’d already been working at Warner Bros. for several months. It was quite a thrill to go into a place, at 17, and be an inbetweener.

Gray: It was a thrill at 23, too.

Monroe: It’s a thrill at 60, to know that you're still able to do it. I’ll be 60 Sunday; Halloween is my birthday.

So I started in ‘34, right down the street here at the old Warner Bros. Sunset lot. I used to play softball, for Warner Bros., in a vacant lot right across the street from where we are now.

Barrier: When you started, were you working for a specific animator?

Monroe: No, in those days they didn’t know if you could inbetween or not, when they first sent you into the room. All they knew was that you could draw. The very first scene that I worked on was a long shot of a baseball game. They gave me an easy scene animated by Fred Horvath. He was a Russian guy who came over here, and was quite arty. He talked himself [into the job of animating]. The good animators would animate the preceding scenes, where the guy hits the ball in close-up, and then you cut to the scene that they gave Fred, as the guy ran around the bases. He had one foot down and one foot pushing off, and then the next foot down and the next foot pushing off. It was my job to put the in-betweens. Nobody told me anything about arcing, or follow-through on action, or anything like that, and when we saw that scene, the guy skidded from one base to another. He was like an ice skater. That was because nobody took the trouble to explain to me that you had to arc them a little bit—that’s an assistant's job, anyway, which I found out later.

When I went home that night, my folks were very anxious to know how I did at Warner Bros. I said, "I made drawings all day long of a guy with a bat over his shoulder, and he never did swing at that ball." Evidently I'd done maybe nine drawings on a cushion, or an anticipation, and he never did swing.

In those days, it was all black and white. There were good draftsmen in the studio, and there were some of us who weren't good draftsmen. I wasn't a particularly good draftsman; I was a cartoonist, and I had my own style of cartooning. So when I went in there, I had a lot to learn. I was immediately thrown in with guys like Chuck, and Clampett, who were good draftsmen, for their age.

[Robert] Bobe Cannon started the same day I did, and we both went up through the ranks. For maybe the first year, we were both inbetweening, but Bobe advanced and became, I think, Chuck Jones's assistant, when he moved to Termite Terrace, when they hired Tex Avery. I was there about a year and a half before they hired Tex Avery.

Barrier: You started there not long after Leon Schlesinger started his own studio.

Monroe: Less than a year; about eleven months after he started it. Bernard Brown was the musician, and then after that there was Norm Spencer, and then Carl Stalling. Bernard Brown was a musician from the main lot, and I don't think he dug cartoons as much as some of the other guys after him.

Barrier: When you started, were you sitting next to an animator, like Fred Horvath, or were you in some sort of bullpen?

Monroe: I was in a bullpen, in a room with Ralph Wolfe and Frank Powers and Tommy Baron and—anyway, there were about six guys in the room. This one guy impressed me so much. I thought he must be the manager; he was telling me what to do. The next day, I found out he'd been there about two days longer than I had.

Barrier: Was there anybody actually in charge of the bullpen?

Monroe: Yes, Johnny Burton was the head of the inbetweeners and assistants at that time. They all answered to Johnny, although they did work for animators. The animators didn't have anything to say about pay rates, or anything like that. All an animator could do was to insist on a certain assistant doing his work.

The directors at that time were Friz Freleng and Jack King, who incidentally was a hell of an animator. But he wasn't the director that Friz Freleng was. Jack King was very big on effects; I remember he taught me how to do water, to make it look wet, rather than like a string of beads. I always enjoyed a certain amount of effects, but I stayed with action animation.

Barrier: It's easy to get carried away with effects, the way Disney did in some of his cartoons.

Monroe: In those days, we couldn't afford it, and they didn't want us to do it. It was on a footage basis, and if you didn't supply them with a normal amount of footage, you just didn't make it. The same guy who I thought was manager had two days or three days seniority over me, and somebody gave him some animation to do. It was a crowd sequence at a prizefight, and it was a close-up of about four characters—all animals. All they asked this animator to do was have them applaud. A quick little four-foot scene. This animator made the mistake of thinking "Aha! I'm an animator!" So in that four feet, which goes by like that, he had this guy applaud once, turn around and nudge the guy next to him, he knocked off his hat, the guy picked up his hat, put it back on, turned around and nudged him, and then they applauded again. His pencil test looked like a bunch of spaghetti.

In my early stages Bob McKimson taught me basic timing, and he taught what 24 frames a second meant, and how long it took to move something. I always thank McKimson for making me an animator. I was animating in the latter part of '35, so it was less than two years as his assistant before they made me an animator. I was almost 19.

Barrier: All of you guys were so young.

Monroe: Yes. I've got pictures that you probably have seen, of all those guys as young people. For example, I have one that I prize. I'm in a yachting cap, in close-up, and behind me, in soft focus, is Leon Schlesinger's yacht, the "Merrie Melody." On the boat are Manuel Perez and a couple of other guys. We used to have a baseball team. We won our league, so Schlesinger agreed to take the baseball team over to Catalina for the weekend. That was in '36 or '37.

Barrier: That's the yacht he bought from Richard Arlen.

Monroe: Yes.

Barrier: You must have become an assistant pretty quickly after becoming an inbetweener.

Monroe: Yes, I wasn't an inbetweener very long. In those days, perseverance had a lot to do with it. Some guys would sit there and be inbetweeners all their lives, and other guys wanted to do something else, so they kidded around and talked with the guys, and the first thing you know, they got a chance to move up. Bob McKimson and I got along well together. I was his inbetweener for a while, and the first thing you know, I was his assistant.

| Members of the animation unit of the 18th Army Air Force Base Unit, the First Motion Picture Unit. I've adopted the identifications published in Graffiti, an ASIFA/Hollywood magazine, in its October 1980 issue, as confirmed and supplemented in 1982 by Frank Thomas. Standing, from left: Lee Hill (Frank Thomas: "Some first lieutenant who knew nothing—army, you know"), Gus Arriola, Gil Rugg, Ralph Chadwick, Norm McCabe, Sam Katz, Herb Rothwill, Bill Higgins, Jack Schnerk, Frank Onaitis, John Kieley, Russ Smiley, Dave Solowas, Ed Becker, Willis Pyle, Frank Thomas, and Amby Paliwoda. Kneeling, from left: Ray Fahringer, Rudy Ising, Dick Thompson, Ozzie Evans, Bernie Wolf, Jules Engel, Ross Wetzel, John Hubley, Van Kaufman, and Ralph Tiller. Seated, from left: Rudy Larriva, Monroe Leung, Manny Gonzales, Boots Marino, Ernie Arcella, Bob Muir (identified by Frank Thomas as "top A.K.," a term I don't recognize), Bill Hurtz, and Phil Monroe. Other members of the unit not in the photo include Bob McIntosh, Art Cruickshank, Bill Scott, Bill Bosche, Don Ruch, Sherman Glas, Bob Givens, Joe Smith, and Ted Sally. Photo courtesy of Rudy Ising. |

I started in '34, and then in ‘43, nine years later, I went into the Army Air Force, and I got into a film unit, at Culver City, and I met guys like Johnny Hubley, Bill Scott, Gus Arriola, Berny Wolf, and Ross Wetzel—a whole bunch of artists who were really good men, from the other studios. It changed my outlook on what we were doing at Warner Bros. Now I love those characters we were working on, but after working on them all of those years, you got tired of doing the same thing all the time. The guys who wanted to go out and do something else found ways of doing it. The Army showed me a different goal, and all of a sudden I became interested in doing other kinds of animation. I also met Frank Thomas, and he offered me a job at Disney's, the same day that Chuck Jones offered me a job to come back to Warner Bros. It was one of my good days. I thank Frank for really teaching me a lot about animation details, but I admire Chuck for his overall approach to animation. I went back and worked for Chuck. We got along very well, after the war. Prior to the war, we had our differences, slightly, but we both overcame that, and after the war I went back as an animator for him, in '46, and I worked for him for the next three years.

I wanted to direct, and eventually I did direct at Warner Bros., but it was many years later. In 1950, I quit Warner Bros., because I was feeling my oats: I was 33 years old, I wanted to direct, I knew I could, so I quit and went to John Sutherland Productions. I met guys like Carl Urbano and Arnold Gillespie and Emery Hawkins: I had met Emery at Warner Bros.. I worked there for about a year, and then they ran out of work, and as with all of the commercial places, they can't afford to keep you on steady, so they laid me off. That was a big blow to me, because it was the first time I'd ever been laid off. I thought the world had come to an end. I was down in the dumps, and Arnold Gillespie, whom I think the world of, invited me out to dinner that night and explained the facts of the commercial life to me. He said, "You'll look back on this some day and thank God that it happened.”

I went from Sutherland to Cascade, where I directed commercials. The job at Cascade lasted a year, and then they ran out of work. I went to work for a small studio called Sketchbook, for Al Amatuzio and Stan Walsh. That lasted a year, and then they ran out of their government contract they had for the things they were doing. From there I went to UPA: I was at UPA in 1951, and I got screen credit on Unicorn in the Garden. I animated about three-quarters of that picture. I worked with Bill Hurtz, mainly, who was the director at that time. He was learning his job, and I was learning the new techniques of animating design characters. That went on for about a year and a half, and then for political reasons I quit. In those days there were a lot of union problems. … I quit Steve [Bosustow], because I couldn't go to UPA and really be happy about anything that was happening. I've seen grown men cry because of situations that existed in those days.

Barrier: You're talking about the blacklist problem?

Monroe: Yes. It was right after that that Johnny Hubley and a lot of the guys were affected. I was friends with those people and hated to see it happen.

Barrier: We talked to Dave Hilberman on Sunday, and talked quite a bit about that.

Monroe: He was very active in the union in those days. Bobe Cannon was over there [at UPA], but he was not very involved in the politics: he just sat there and drew.

Barrier: Hubley was, I guess, the premier guy that studio lost because of the blacklist.

Monroe: Yes, I think so. He really led that studio as far as new styles and new developments and new approaches—he was an inspirational guy to work for He was one of the most inspirational, along with Chuck, in a different direction. I animated whole pictures for Hubley.

Barrier: After he left UPA?

Monroe: He was in that Army group, and we got to know each other there. After that, I worked for Storyboard Productions. They had a great group over there.

Barrier: The story I've heard about what happened at UPA in the early '50's was that Columbia gave Bosustow an ultimatum to fire certain people—the ones who had been blacklisted—and that they then met and decided to quit as a group, rather than bring the studio down.

Monroe: I came to UPA as an experienced animator, and they didn't have experienced animators, outside of Bobo Cannon and Rudy Larriva, at that time. They had a bunch of young guys. So I came in as an animator, and wasn't politically involved in the studio. But it sounds right to me. I do know that when Hubley was ousted, a couple of other guys were, too.

Barrier: Chuck Daggett, I know, left about the same time.

Monroe: There's a name I remember, but …

Barrier: He was the publicity man for UPA.

Monroe: Yes, that's right. I remembered the happy days at Warner Bros., when we didn't have anything like that.

Barrier: Nobody was politically oriented.

Monroe: That's right. We had union problems, but we just solved them by not getting too involved with outside interests. I'm sure glad I was over there, because that experience I had with UPA—and I worked with Hubley on Rooty Toot Toot, and I worked on some of the Magoos with Pete Burness, but not too many, because they had me active in the other end of it. I was a back-up guy for Bill Hurtz, in a way, because I was his most experienced animator.

Barrier: There's a controversy of sorts over who was most responsible for the animation in Rooty Toot Toot. You hear that Babbitt was, or Natwick was …

Monroe: I would say that Babbitt had more, as I remember it, because Grim Natwick wasn't there all that long. He came in after I had started, and he was there just a short time.

Then I left, and I don't know how long he remained. I remember that Art Babbitt was kind of a supervising animator on the picture: he was the guy who would analyze your animation before you had it tested. And with the beginning animators, he really put them to the test. The more experienced animators would say, “All right, Art," and then we'd go back and do it our own way.

After UPA, I went back to Cascade and with Alex Lovy and a couple of other people … Frank Tipper … After that, I thought I'd like to free-lance. I free-lanced one week, and then Ray Patin offered me a job, in '54, I think. I worked for Ray Patin from '54 until almost 1960. During that period, I directed everything that I worked on. I recommended Ken Champin, a great animator, and told him to forget animation and get in there and direct. He ended up by being a better director than I was.

I quit in '59, because Chuck Jones had been over to Patin and met the people I worked with, and saw what I was doing commercially—I was also teaching at the time. He talked me into coming back to Warner Bros. and heading up their commercial department, and also to finish the Bell Telephone science series. I went back in 1960 to finish a picture that Bob McKimson had started. There were two pictures in the works, and I finished the one Bob McKimson was working on, and started one called All About Time. It was with Professor Baxter, who starred in the Bell science series films. I had Benny Washam animating for me, and Al Ignatiev—just a great bunch of guys. Then, when I finished that picture—and I think I worked on three of those, in pieces; one of them I received animation direction credit on, the other two I finished up for Bob McKimson. After that contract came to an end, in '61, they put me on entertainment, and I directed three or four entertainment things—Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck—and one for Chuck, with Ralph Wolf and the Sheepdog.

Then I got so busy in commercia1s—Dave DePatie was the producer, and I was the director and the head of the commercial department.I started Charlie the Tuna and directed the first Linus spots. Hawley Pratt and I helped develop the characters. I worked on the Gillette commercials, too, with the little parrot: when Chuck was busy doing the entertainment cartoons, I took over and did those things for him.

I really scored with Charlie the Tuna. They were funny, with a good solid character, and good animation. I had Manny Gould animating for me: in fact, I kept the whole studio busy, for a while, because they weren't doing entertainment cartoons for a couple of months. I got this offer from Leo Burnett, in 1962. They came to me to find a replacement for Bob Wickersham. He had had my job in Chicago, at Leo Burnett, and he died at the age of 50 or 51. [Wickersham died April 21, 1962, at the age of 51.] They needed a replacement for him, but the catch to it was that you had to go back to Chicago. In 1962, I could see the handwriting on the wall at Warner Bros.—that thing was folding fast—and I could see that they weren't going to be making any more entertainment shorts. I was head of the commercials, and that was touch and go, because you're only as good as your salesmen are. So I took this opportunity to come to work at Leo Burnett.

Barrier: Did you go to Chicago?

Monroe: Oh, yes. I was there for nine years. I froze my ass off. My son still lives in Northbrook.

Barrier: I want to go back and talk some more about your work at Warner Bros. You mentioned that you got along well with Chuck after the war, but that before the war you had differences, and I'm wondering if that relates to something that Chuck told me. He said that particularly when he first started directing, he was very much animation-oriented, and the character layouts that he would give the animators would frequently be so detailed that they amounted to animation extremes, and this would be confining for the animators. Later on, he gave the animators more leeway. Were you conscious of that sort of thing before the war?

Monroe: No… Before the war, they had a way of classifying animators; they were "A" animators or "B" animators. The "A" animators were the guys who were able to do a sufficient amount of footage and do it acceptable to the director. Before the war, when I worked for Chuck—I worked for Chuck until about 1941. We had a difference of opinion, but it wasn't anything in regard to the way he was directing. It was a little political, in those days: it had something to do with the internal running of the studio, and I didn't agree with him. I didn't talk to Chuck, I wasn't around him: I was a social friend of his, up until that time. In 1946, we shook hands, and from then on we've been the best of buddies. It was silly: we didn't agree on a certain person in the studio, and the way they were conducting their business. Chuck had his mind made up, and I had mine made up. I was feeling my oats, and I wanted to be my own person.

After I left Chuck's unit, I worked for Friz, for a year. Then Bob Clampett needed an "A" animator—a guy to handle a particular amount of footage—and they transferred me into Bob Clampett's unit. He had Rod Scribner and Bob McKimson… I think Bill Melendez might have been in Clampett's unit at that time. Tom McKimson was animating, too. I was there six or eight months, and I’m in that group picture of Clampett’s unit. That was 1943, and people my age—I was 27 at the time—felt they wanted to enlist and do something: some of us did, a lot of them didn't. I think I was the last animator to leave Warner Bros. I volunteered and ended up in an animation unit, after about six months. I was thankful for that, because I’d had enough of the Army basic training by that time.

Barrier: That was Rudy Ising’s unit, I guess.

Monroe: Rudy Ising, yes, and Ray Fahringer, Captain Fahringer. He was an old Warner Bros. animator, and he worked for a short time at UPA. He was a good friend of Cecil Surry's.

| The Chuck Jones unit in the early 1940s, identifications by Chuck Jones. Standing, from left: unidentified, Lee LeBlanc, John McGrew, Ken Harris, Gene Fleury, unidentified, Abe Levitow, Chuck Jones, Ted Pierce, Roger Daley, Alex Ignatiev, Dick Jones, and Roy Laufenberger. Kneeling, from left: Phil Monroe, Monroe Leung, Ben Washam, Bob Doerfloer, Phil DeLara, Bobe Cannon, Rudy Larriva, and Jack Phillips. Photo from Chuck Jones. Photo courtesy of Chuck Jones. |

Barrier: You worked for three very different directors, Chuck and Friz and Bob, in that short space of time. You must have been aware then of the differences in the way they approached animation.

Monroe: I sure was. Chuck did control his animators quite a lot, through his layouts. He’s such a good draftsman, and he did his own type of layouts to the point that you could go in one of two directions. You could either do it his way, exactly, or you could start using your imagination a little bit and changing his stuff as you went along. His "A" animators did that—Benny Washam, Abe Levitow, Ken Harris, Bobo Cannon and myself. He had some "B" animators who eventually became "A" animators. Ken Harris would take a Chuck Jones layout, a pose, and he'd milk that damned thing and get everything out of that one pose, and add extra little things to it. Ken was, and still is, an excellent animator. You could do that with Chuck, and when you finished the job, it was recognizable as a Chuck Jones-styled picture.

Friz Freleng would make funny little drawings, and you'd see comedy in them, and you'd go ahead and draw them your way; but you had to make them act the way Friz wanted them to act. He taught me a great thing; probably Chuck tried to teach me [the same thing], but it didn't sink in. Friz taught me, very quickly, that if a thing doesn't read well in silhouette, it doesn't read well at all. I became a better animator working for Friz, in a short space of time. I admire Friz's timing a great deal.

Friz was a very difficult guy to work with, because you never knew what he wanted. You sure did know what Chuck wanted, and he was much easier to work for. Friz never knew what he wanted until he saw it, then you'd go back. Friz told me one time, "The last six months you were with me, you were really a good animator." He forgot about the other six years. I started out with Friz, then I went to Chuck, and went back to Friz. Then, just briefly, I worked for Bob Clampett.

I don't know what kind of a director Bob Clampett was. He timed things the way he liked to see them timed, but he was a frantic director. He didn't draw very well, and he seemed to get a lot of fun out of direction, he didn't seem to take it too seriously, when you were working for him. He liked guys to take it seriously, and do a good job for him, but he never was really—he was not the kind of guy to teach you. But he was a better animator than Chuck was, actually, when he was animating. I remember in 1934, on Mr. and Mrs. Was the Name, Bob Clampett doing some beautiful underwater stuff; it was slow-moving, it wasn't frantic, it was very well animated. I always admired Bob as an animator; I couldn't understand him quite as well as a director.

Gray: When you say that Clampett was a frantic director, do you mean that his pictures were frantic or he was frantic?

Monroe: Both.

Barrier: When he would be handing out a scene, was it hard to get a clear idea of what he wanted?

Monroe: Oh, yes. Just chicken scratches … he'd throw you a piece of paper. I got along well with Bob, gag-wise. In fact, when I was an inbetweener for him, we used to kid and gag around, and he used to give me credit for a lot of the gags that I'm sure weren't mine. We really had a good relationship, as far as that it goes.

Barrier: He'd be adding gags in his animation?

Monroe: Oh, God, yes. He'd do a rough, and if he could think of a gag that fit in with that particular rough that wasn't on the storyboard, he'd put it in. That indicates to me that his direction was of a loose, frantic, improvising nature. He never did quite come out of that.

The guy who was the least effective director was Frank Tashlin. I worked for Tash; I went from Friz to Tash to Bob, that was it.

Barrier: That would have been just after Tash came back from Screen Gems. He took Norm McCabe's spot.

Monroe: That's right. [On the transcript, Phil circled that phrase, and the sentence about Norm McCabe in my preceding comment, and wrote "wrong," apparently forgetting that he animated for Tashlin twice: during Tashlin's first stint as a Schlesinger director, in the late 1930s, and then again, at least briefly, after Tashlin returned in the early 1940s. He went from Tashlin to Jones to Freleng to Tashlin to Clampett.] Again, he was a keen guy to work for, but his pictures, as I remember them, when he ran out of ideas he'd start shooting montage effects. His pictures weren't too good, story-wise, but he did have a lot of good production in his pictures.

Barrier: I want to get a clearer picture in my mind of what these different directors would give you, when they were handing out scenes. I assume that Chuck would give you lots of character layouts and, I assume, exposure sheets with very precise timing of a scene.

Monroe: Yes, his exposure sheets always indicated the action that he wanted—not to the frame, but he would have, in a six-foot span, two or three notations of attitudes that he wanted. He was very descriptive, and able to talk well, and make himself understood. To me, he was always able to describe things so well.

Barrier: This was in writing, on the exposure sheets.

Monroe: On the exposure sheets, and also on his drawings. He'd make a drawing and write little notes to you, on the drawing, to show you what the attitude of that character should be for the next four to six feet, or maybe the next twelve feet.

Barrier: Did he do much in the way of acting out, and very verbal explanation, or did he rely on the drawings?

Monroe: Mostly he relied on the drawings. He very seldom got up and acted anything out. He'd sit in his chair, and talk to you, and make faces, and gesture, and you'd get the feeling out of it.

Friz would describe something to you, and he'd be acting it out, more or less. But Friz did not draw too much. He'd make little scribbles, and he'd turn them over to his layout man, and you'd work with his layouts. I was never privileged, as an animator, to work with Hawley Pratt, Friz's layout man; but Hawley Pratt could draw like a bastard, he was really good. He would take Friz's roughs and make a good drawing, getting the same thing that Friz got into his rough drawings. He was doing the same thing that Chuck Jones did, by himself.

Barrier: Who was doing Friz's character layouts when you were animating?

Monroe: Nobody. He would have a character man do a model sheet. I think Bob Givens worked for him for a while, a couple of Disney guys worked for him; Don Towsley worked for him. He would do a character model drawing, and we would work strictly from Friz's roughs—which were real rough. If he wanted a guy with a big grin, he'd give you a character with a big grin on his face, and boy, your character had to be drawn with a grin on his face that came off as well as that rough, or Friz'd think you changed it. Friz was a harder guy to work for, because you had a harder time doing your footage. Those guys really had to bust their backs to get their footage out for Friz.

Gray: Well, with no layouts, just those scribbles…

Monroe: That was what slowed you down. We had Gil Turner, who was a good draftsman, we had Dick Bickenbach, who was another good draftsman; we had Ken Champin, Gerry Chiniquy, Manuel Perez, and myself, in one unit. I don't know if we were all there at the same time, but that was Friz's unit for the two or three years right prior to the war. Those guys were all good draftsmen. They did not draw like Chuck draws—I mean in the same style—so Chuck didn't really know them, as draftsmen. He liked you to follow his way of drawing, and do it his way. I had a little bit of a problem with him that way. I wanted to do it my way, [although] maybe my way wasn't as good.

So with Friz, I was really happy. But, maybe because of Tash coming back, they had to take experienced animators and move them around. I was one of the last guys to come into Friz's unit, and I was the first one to leave.

Barrier: Now, Friz's drawings were not usable to you at all, as animation drawings?

Monroe: No, you had to redraw everything that he did, in order to put all the details in and finish the drawing. But his roughs were extremely descriptive: you knew immediately what he wanted—or you thought you did.

Barrier: Were his exposure sheets as detailed as Chuck’s?

Monroe: I think Friz was an excellent director of timing. There's nobody in this business as good as Friz is, at timing.

Gray: Can you tell us what it is about Friz's timing that you admire so much?

Monroe: It's a subtlety of timing that he gets into stuff, like a good stand-up comedian or pantomime artist. Friz would not hold a drawing in a scene longer than was necessary. Friz would go into a cute pose, he’d wait there long enough, and he'd break out of it, and it would break you up. I think another thing that helped Friz was that he was a musician. I don't know how good a one, but he reads music, he understands music, and he understands timing, which is essential in animation. Chuck, to this day, doesn't really read music, but he's made a hell of a lot of good musicals.

Barrier: Friz was the only Warner director, I know, who worked with bar sheets, and made his exposure sheets from that. Chuck said he had never used bar sheets.

Monroe: No, Chuck didn't, but Friz taught me bar sheets, and I’ve used bar sheets for twenty-five years. It's the only way to go, because you've got your whole picture right there in front of you. If one sequence is too long, you can look at that bar sheet and immediately see, "I've put too much footage into this."

I've always been a good audience. I used to go into screenings, and if I was working for one of these directors, and they showed another director's picture, and it struck me funny, I would laugh. I have an infectious laugh, I've been told, and more than once, both of these directors have come to me and said, "Why in the hell don't you laugh like that at my pictures?" Friz and Chuck both said it..

Barrier: What did Clampett and Tashlin give you, compared to what you got from Friz and Chuck?

Monroe: Clampett would work the same way that Friz did, to a degree. Clampett would set his character pretty much; he probably spent a lot of time with his layout men there, getting those model sheets down like he wanted them, and getting the drawing like he wanted. But when he passed a scene out to an animator—he was always a picture and a half behind anyway, and he would rush it out. He'd say, "Oh, God, I've got 35 feet here to do. Let's start here and have this guy run along here, and Porky Pig jumps in here and joins him here, and we go down here … " And the first thing you know, you've got—by word of mouth—what he wanted to have happen in the scene. That is good experience for an animator, because he has to do it himself. Rod Scribner was a hell of a good animator, and he didn't get much direction.

Barrier: Rod's stuff looks so much different when he was working for Clampett than when he was working for Avery or McKimson; it's like he was unleashed.

Monroe: He was. Clampett just loved his stuff, because it was real wild. A guy sticks out his tongue and it goes out eight yards, and his eyes bulge out, and then WHAP! he's into another action, in no frames he's doing something else. That's exactly the opposite of Chuck's approach to animation. They were both quite outspoken in their approach to what they wanted.

Barrier: On Chuck's pictures, when you had detailed character layouts, did you also get a model sheet. or did the layouts serve that function—

Monroe: [Phil indicated that he worked with model sheets as well as Chuck's layouts, and showed several, including one for Sniffles.] This was when Chuck was going through that slow period. I animated a waltz one time for him, and he never has forgotten it; he said it was the best piece of animation that I'd done. Sniffles was waltzing, by himself—

Gray: Oh, yes, in Bedtime for Sniffles (1940)..

Monroe: Nobody else knew how to dance in our unit. In those days, I was going to dances once or twice a week, so I animated this dance for him. But it was all slow timing; it seemed like it went on for hours.

You asked me about model sheets …

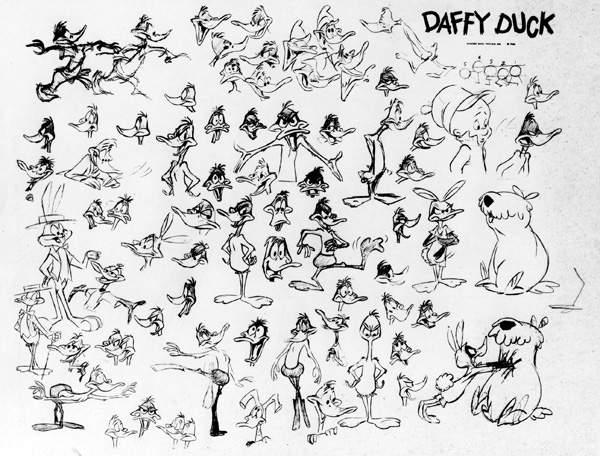

| A late Daffy Duck model sheet by Chuck Jones. The poses are from Robin Hood Daffy (1958), The Abominable Snow Rabbit (1961), and the Bugs Bunny TV show, among other places. Courtesy of Milt Gray. |

Barrier: Now, the poses on these model sheets [later model sheets for the Coyote and Daffy Duck] are actually from Chuck's character layouts, I believe …

Monroe: Yes, they are. Chuck has always used his own drawings. What he does is lay out a scene and then go through the picture and take drawings out and make a model sheet out of them. If you're working on a scene someplace down here, and you need a model, you look up, and here's the way he looked in that scene, and here's the way he looked in this scene, and that will help you in another picture. Once you got these, this would work for a whole series of Coyote pictures: you wouldn't have to do a model sheet for a year and a half, before you'd change anything.

Barrier: How did Chuck cast you, what kind of action did he put you on?

Monroe: You've heard before that some guys were good character men, some guys were cute animators, some guys were dance animators, some guys were just plain action animators. For a good long period of time, prior to the war, from, I'd say, 1936 to 1942, when he was just getting started as a director, Chuck had Bobe Cannon, Ken Harris, and me. Bobe was very good at cute stuff; he liked to draw cute little things. Ken Harris was the character man; he would give Ken anything where a guy had to act. Consequently, I ended up with all the action stuff. I always wanted to do the character things, and once in a while he would give me a character thing and I would break my back to do a good job on it.

Another thing that's very important to animators—aside from working with the director, and I've told Chuck this, many a time—an animator has to have a good assistant, and I mean a really good assistant. I never had one, all the time I was working. I would always pick a guy for his personality—some guy I liked to work with—and I ended up with some of the lousiest draftsmen.

I had one little guy who couldn't draw anything, and he was my assistant three years before he went in the Marines and two years after he came out. Ken Harris had Abe Levitow, and Abe was a terrific draftsman. Benny Washam does his own drawing: he draws so clean that he really doesn't need an assistant. But a guy who roughs out things, like I did—if I'd had a good assistant, I think I would have probably had a lot more character scenes given to me in those days. My timing is very good—Frank Thomas told me it was, in the Army. He said, "If you took more time with your drawing, you'd be one hell of an animator.”

Barrier: On this trip, we've talked to a number of animators about the roles assistants played, and how important they were…

Monroe: If a guy loved to rough out stuff, like Don Williams, he needs a good draftsman as an assistant. Someone who will watch sizes, volumes, and detail. When my assistant's drawings would come back to me, I'd say, "In order to change this like it should be, we'll have to change the whole scene." I never had the luxury, really, of having an Abe Levitow, or somebody like that, following me up. It's a very important thing to surround yourself with the best people in each department.

Barrier: Generally, assistants, as they've developed from the middle '30's, seem to be draftsman, who provide cleaned-up extremes, and maybe rough in the inbetweens for the inbetweener to clean up—or any of a number of systems. Is being an assistant, and doing cleaned-up work, really good preparation for being an animator who does the kind of work you've been discussing, quickly roughed out work?

Monroe: Well, any experience is good experience. These guys who draw well don't have to fight it when they do become animators. If they study and analyze the scenes that they're working on, there's nothing to keep them from roughing it up themselves eventually. It's not a deterrent: it's up to the individual to decide how much he wants to push himself. There are professional assistants, but actually, a guy who's studying animation should try to learn how to animate, and move up. That's what I did, before I was ready. I don't think I was a very good assistant when I assisted Bob McKimson …

Barrier: Bob is such a neat, precise animator …

Monroe: I could be neat; as an assistant, I could be neat.

I should say, before I go any further, that Bob McKimson was probably more responsible for whatever success I had as an animator, he's probably just as responsible as Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng. He taught me the basics of animation; he's awfully good at that.

Barrier: Was he kind of the senior animator at the studio when you were starting there?

Monroe: When I first started there, he was just one of many. Bob was just one of several good ones. They had Ham Hamilton, who was the best damned animator that Warner Bros. ever had: he was my second cousin. Disney always said that he was one of his best animators, too; he worked for many years at Disney. Then they had Ben Clopton, who was a dance man. I think Ben's still alive, and doing well, but he had many rough years. Cal Dalton was an animator, and Paul Smith, and Frank Tipper—he later got out of animation and went into background work.

Barrier: Bob told me, when I interviewed him several years ago, that at one point he became the head animator in the studio, and oversaw the work of the other animators.

Monroe: That's right; right before he went into direction.

Barrier: He would check on the animation and see that it was technically correct, is that right?

Monroe: That's right. You know the reason for that? Because of Clampett, Friz, and Chuck. They couldn't get together on how to draw Bugs Bunny or Daffy Duck, and New York kept saying, "My God, that Daffy doesn't look like the Daffy there, and that Bugs looks like an entirely different Bugs…" They couldn't have any consistency. And so there was a great big to-do in the studio about who in hell was going to bring this all back. They all did their own idea of what Bugs should look like, and they handed it in.

So, at this one time, before Bob started directing, he was the supervising animator, and he had to check your scenes before you had them pencil-tested. And if he didn't like the way you drew it, you had to go back and draw it another way. But Bob was smart enough to be flexible. With a guy like Rod Scribner, who was loose as a goose, and working for Clampett, Bob wouldn't begin to change Rod's overall approach. But when he got them into a held position, or something like that, Bob would have a few suggestions for bringing them back. He was not too critical of the other guys' drawings. He drew them well enough—he made all of those old, original real tight drawings of Bugs Bunny, and he drew everything like that. He pleased more of the guys, the way he drew, than any other animator did, so they did make Bob a supervising animator.

Barrier: So he was basically responsible for keeping the animators' work on character.

Monroe: That's right.

Gray: He sounds like what at Disney's was called the head clean-up artist.

Monroe: It was, more or less, that kind of a situation. He only dealt with the standardized characters. We had a lot of other characters that you could go any direction on, and he wouldn't say anything about those. His job was to unify the way that everybody was drawing Bugs Bunny, so they all accepted Bob's layouts as being the way to draw Bugs Bunny. Friz Freleng worked with that layout [i.e., model sheet], and so did Chuck Jones, but the way Friz's animators would do him, he'd still wind up looking a little bit different from Chuck Jones'.

I was a very close friend of Bob's and still am, and I kept encouraging Bob to go into direction. I said, "You've been doing it for years, and you've been changing all the guys' drawings, why don't you do it?" I talked to him like a Dutch uncle, and finally when he did start directing, it was no problem for him at all, he went right out and directed.

Gray: When I've asked Bob Clampett how he directed, how he got a certain feeling into his pictures, he'll go into great detail about how he would talk to each animator, individually, go through the storyboard with them, play up the story to them, get them in the right mood, give them all kinds of rough sketches-which he admits were very crude—inspire the hell out of them, send them back to their rooms so inspired that they couldn't wait to start working.

Monroe: His strongest point would be that when you talked to him about the over-all story, he'd get you enthused with his story points. He wasn't a bad guy to work for: he always treated me, and all of his animators, fairly. It's just that a lot of times you'd be working on something that your heart wasn't in, because maybe you didn't agree with his taste, or his humor—something like that. But he did talk to his animators. He was always willing to talk to you. He would get up and act out something; he was very descriptive, and able to do that. But he was no help whatever when it came to the drawing of it, and that's the name of the game. Chuck was a big help, in fact, too much help at times. Some guys didn't want to work for him, because he did too much of it. When I got away from Chuck, and found out there were other kinds of directors—the most inspiring director I ever worked for was Johnny Hubley, and boy, he didn't draw anything like these other guys. But he could sit down and talk to you, and the first thing you know, you'd be chomping at the bit to go in there and get busy. Bob Clampett had an awful lot of that in him, and I don't disagree with him there.

Barrier: It sounds as if you're saying that he was mostly involved in the stories, and left the actual animation pretty much in the hands of the animators.

Monroe: That's right, he would. So it was his animators…

Barrier: Who bridged the gap between his story and the finished product.

Monroe: That's right. A lot of the wild things he did, there was no other way to do it but wild. So your picture looked wild, and it didn't make sense. And you often wondered, "Gee, why do you want that guy to smell that kid's armpit?" [An evident reference to a scene in Hare Ribbin’ (1944) in which a dog smells Bugs Bunny's armpit.] "I think it's funny." "Well, okay."

Barrier: When you were in the Army Air Force, you were working with Disney-oriented people like Thomas and Hubley, what was markedly different about their approach that you had not encountered before?

Monroe: We did training films, and because there were no salaries involved, we were able to give them good, full animation, and learn animation as we went along. At that time, I’d been in the animation business for nine years, and I'd been an animator about seven years when I went into the Army. These Disney guys recognized that I'd had some experience, and they were anxious to use me, as an animator. The animators I worked with were Rudy Larriva… Bill Hurtz, Willy Pyle, Frank Thomas, and Norm McCabe. Frank Thomas really kept most of us interested in that job, for a while, and then it was Johnny Hubley.

Frank Thomas was directing the big, Disney-like productions that we were going to do, and Hubley was working as his story man and layout man. Frank Thomas made us all analyze our animation, as they did at Disney's. He would spend two hours on a little bit of action of a guy's head raising up, to show you the volume, and the squash, and the drawing. He always worked on about six drawings at the same time. This was a little bit different than the animation at Warner Bros. Frank helped me out a lot; he gave me the old Disney treatment. He told me if I could draw better, I'd be a hell of an animator, and I never forgot that. From that day on, I concentrated more on my drawing.

Then, Hubley was given some spots to do, and they were quickies, for the Army, that had to be done in a hurry. He'd do these great, knocked-out layouts. I'll never forget one he did of a guy who was completely laid up in combat; he was completely covered with bandages. The only thing they showed was his nose sticking out; everything else was wrapped in bandages. He had one leg propped up in front of him, and the other leg was down, and the only other exposed thing on his whole body was his big toes. He had this funny pose, and his toes were going back and forth, and I had a rhythm thing going on his toes. Hubley loved it, and he was right—it got a little bit of a laugh in a very dry picture. Hubley was the kind of guy who could inspire you with simple things.

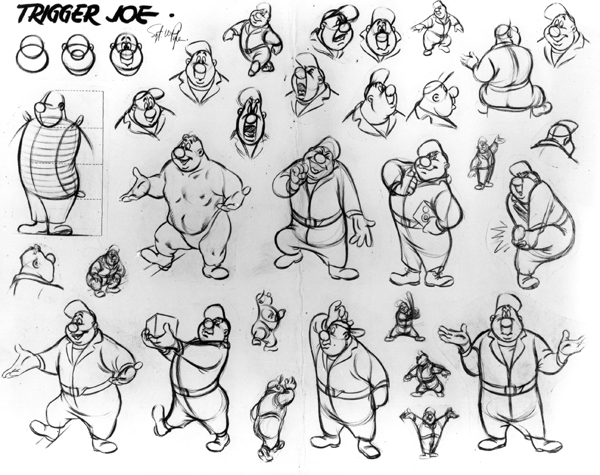

| An FMPU Trigger Joe model sheet. Courtesy of Bob Allen. |

Barrier: Was it the Trigger Joe series that you worked on with Thomas?

Monroe: Yes, that's right. Trigger Joe was directed by Berny Wolf, too. Then Harman-Ising [Phil probably meant Hugh Harman Productions], who was in business at that time in Beverly Hills, sub-contracted some pictures for us, and George Gordon worked on Trigger Joe, as a director for Harman-Ising.

In 1946, I came back to Warner Bros., and Chuck and I really enjoyed each other's company a lot. I was probably a better animator because I'd worked with Frank Thomas and John Hubley. We just got along great for four years, but at the end of four years, I got tired of Bugs Bunny, and Daffy Duck, and working for somebody else. I knew the answers to direction—or thought I did—and I was anxious to get started. Eddie Selzer, at that time, had promised me the next unit, which never came to pass; he never formed another unit.

Barrier: They dissolved Art Davis' unit around 1950 [actually, two or three years earlier]. Was that sort of a signal to you?

Monroe: That's right. Actually, when Artie got his unit, it was a disappointment to me, although I love Artie, I really like him. I wanted that job an awful lot. A couple of guys were disappointed at that time. After you've been around 16 or 17 years, animating, you know the answers to animation problems, and I thought I had a pretty good gag mind, and somewhat of a story mind, so I was ready; but they weren't.

Barrier: How did they go about choosing a director in a situation like that?

Monroe: In those days, the other directors had a lot to say about it. I was considered as a director—I was told so by Eddie Selzer—and I was shot down by the other directors saying that I needed more layout experience. Artie Davis had had directorial experience, and that was pretty hard to fight. They didn't want to go with an unknown guy, and when they did suggest me, one or two of the directors said I needed more layout experience. Anyhow, that's one of the reasons why I eventually left, with no hard feelings toward them. I was 33 years old, and if you don't make it in the next ten years, you don't make it. I just went out in the commercial world, and boy, have I been happy.

Barrier: You said you knew you could handle a unit; why was that?

Monroe: I always like a good time, and I don't take myself too seriously—or I didn't in those days. When I came back out of the Army, I got interested in square dancing. There was only one other guy at the studio who had any experience [square dancing], an animator named Dave Davidovich. He was a Russian character who just loved square dancing. He talked me into going one night, and I fell in love with this thing. It's a way of living, really, and square dancing was taking off like a house afire. Nobody at Warner Bros. had heard about it.

I got everybody going. Treg Brown was a student … Chuck Jones, it changed his whole life. I introduced him and Dorothy to square dancing. In the old Warner Bros. studio, there was a basement downstairs, and at one time I had three squares dancing down there. Twenty-four people dancing at one time, downstairs at lunch time, and they liked it so much they wouldn't stop. The guys would bring their lunches down. One day I had Johnny Burton, the head of the studio; Eddie Selzer came down and watched it, many a time. I had Friz Freleng and Chuck Jones dancing in the same square, and in those days they were barely on speaking terms. Artie Davis was dancing, Bob McKimson was dancing. I had the whole studio going.

Eddie Selzer noticed that, and the way I handled people. He told me, "You're good with people, and you get 'em going. I think you can direct. We’ll keep the next unit open for you.” And it never happened. So I felt disappointed, and I left. Chuck went on in square dancing, and became one of the leading West Coast speakers. I was president of a club in Encino, called the Wagon Wheelers, and I invited him one night, as a friend of mine, to make a speech to these square dancers, and he decided to do it, because he'd been doing it at his own club, just entertaining his own friends. I invited him over to my club to do it, and he was an immediate hit. From that night on, he just went on, and he started wearing cowboy hats to the studio, with boots. He was dressed for square dancing, for about four to six years. It was a big thing in his life. He became known as Pappy Jones, or something like that. I expected him to start chewing tobacco.

One time, I did a chalk talk for a group of about two hundred square dancers, as part of the entertainment. I got up and made gags, and I drew Bugs Bunny and Porky Pig, and Chuck was encouraging me from the audience. Then he said, "I wish I had that kind of ability.” In those days, he wouldn’t [give a chalk talk of that kind]. I was always proud of that, that I helped him come out of it a little. So, that’s why I know I could handle people, and I could handle animators. I’ve never had any problem getting along with the animators who worked for me.

Gray: Jumping ahead, I'm wondering about what happened toward the end of Warner Bros., when you were directing theatrical shorts, how that came about, which unit you took over.

Monroe: It wasn’t a matter of taking over a unit. Chuck, Bob McKimson, and Friz were directing, and they all had their assignments—this was in 1961 or '62. They had just so many pictures to make, and they wanted to finish them by a certain time. I was being paid a pretty good salary, as a director, and I ran out of commercials, and industrial or educational things. So they just gave me entertainment. I’m in the '62 yearbook as one of the four directors, right before I left the studio. I had been directing there for three years.

Barrier: Was there any of this commercial and industrial animation going on before you left the studio in 1950?

Monroe: Very little. Maybe about three years before then, there was the start of it, here in Hollywood, but there was no commercial department at Warner Bros. until Jack Warner accepted television as being all right to have in your house. For a while, he wouldn't allow guys to buy a television set. He was one of the last guys to ever give in on that. Then, all of a sudden, his studio was the mecca for all of the hour shows. At one time, in 1962, we were doing nine hours of television production, on that lot, in one week. We had every stage going.

They started the commercial department at Warner Bros. sometime in the late '50's, and Jack Warner Jr., who was a friend of Chuck's—or Chuck knew him—set up the department, and they had some pretty big guys in Hollywood, at that time, associated with the commercial department. They had a lot of good accounts going in and out of that studio at that time, but they blew it, and people eventually didn't want to have their commercials made there. Finally, it got to the point that the only commercials they did were the ones that they had to do. For instance, they had the Bugs Bunny show, and they needed commercials for that. So they hired me at the tail end of that whole commercial thing, and Dave DePatie was head of it, as producer.

Barrier: Of the commercials?

Monroe: No, he was head of the cartoonists. When I went back, I was working for Dave DePatie, and I didn't know anything about him. He treated me very fairly, and I worked with him about two and a half years. I built up a nice commercial thing for him, which eventually he and Friz took over.

Barrier: Of course, you didn't go with them to DePatieFreleng…

Monroe: No, at that time, I'd already accepted my job here.

I got into music recording, and voice, and working with talented people, and I just love the agency side of it. Because I can still animate, I found out. In two years, when I have to retire, I can still go back to any phase of production that anybody needs, because I've done it. My first love is animation, and if guys like Chuck Jones still think I'm a good animator, I may just do that, and forget about all the other.

Barrier: Phil, I want to put you on the spot, because you've alluded to something several times that Milt and I have run into and that's been a constant problem for us, and that is the apparent rivalries and conflicts among the directors at the Warner studio.

Monroe: It was professional jealousy, I think. They are all artists, and they were just jealous of one another, that's all. I've worked for every one of them, and I've heard them all talk about the other guys, to an extent. But golly, they're all grown men, and they all ought to realize that there's a place for everybody. I've certainly mellowed about it. But when I was there, there was a lot of competition. They were competing like mad to do funnier pictures than the other directors. It meant more money to them, more recognition. A lot of times, two or three of them would side against another one.

Barrier: Was there much visiting back and forth, exchanging ideas, or was it pretty much a matter of keeping your group together and competing with the other groups?

Monroe: It was pretty damned tight, yes. I would say there was very little exchanging ideas at the old Warner Bros. studios. Maybe that's why they were so successful.

Barrier: Was it different before the war than after the war, or was it the same both times?

Monroe: Before the war, they had more guys in the story department, and it hadn't boiled down at that point to Mike Maltese and Warren Foster [and Ted Pierce]. Prior to the war, it was a lot of different guys, and because I was not in that department, I don't know how much they contributed. But being around there every day for seven or eight years, you get a pretty good idea who the guys are who do a lot of the work. They had a lot of good story men there. I gave Bill Scott his first story job there, from the Army: he was in that same Army unit. They needed a story man, and I went into Eddie Selzer, after talking to Chuck and Friz. I said, "Hey, there’s one guy you guys have got to get to know." I brought him in and they hired him. He was my assistant in the Army. He’d never drawn professionally, he was a school teacher from Denver, and he was a funny, funny man, and a funny cartoonist, and I’ve got thousands of his drawings at home. I taught him to inbetween, and become an assistant. And he hated it. He was a writer, a gag man, and a very prolific guy, and a smart man.

Barrier: He was Artie Davis’s gag man after the war.

Monroe: But not very long, because he was aced out by somebody, I don't know who he was. They didn't give him a break there, so he left and went over to Sutherland's, and became very big.

In answer to your question, the story men there were quite protective of their jobs, and it's been told to me that other story men who went in there had a hard time breaking in.

Barrier: Yes, I've heard that [from Mike Maltese]. This was before the war, when they had Bugs Hardaway and that group.

Monroe: It was the truth. A guy'd go in there and he’d come out talking to himself.

Gray: We've heard about the group sessions when all the directors and their respective story men would go in as a group and help gag up one another's cartoons.

Monroe: That was after the war. They started that system, but actually, the story man would work with the director and get that story completed, and then, in one jam session, they would call all of the other directors and story men in.

Barrier: Why did you go back to Warner Bros. after the war instead of taking Frank Thomas's offer and going to Disney?

Monroe: It was a very hard decision to make, because Frank Thomas had worked with me for three years and he had finally decided I would be somebody who would enjoy working at Disney's, under him. He did hire Rudy Larriva, who was with me at the time [in the First Motion Picture Unit]. Prior to the war, Rudy was with Chuck Jones. I felt more comfortable at Warner Bros., and I felt maybe I'd get ahead faster. At Disney's, I would be just another animator. I wasn't afraid of that, but I wanted to progress.

Barrier: How did Chuck handle you differently as an animator after the war?

Monroe: I was my own guy, after the war. Before the war, he was surrounded by a bunch of people who were very close; they socialized together, and everything like that. I did that for a few years, and then I broke away. Then, when I went back—again, this square dancing thing is one of the big things… Instead of me going to his way of doing things, he joined in something we both enjoyed, and we became close friends through that. We were so close when we were young; we used to go up to San Francisco together and raise hell. We used to go to the Stanford-USC football games up in Palo Alto.

Barrier: In the actual direction—in handing out a scene, say—what was different? You've touched on this briefly, but I'd like to get a little more into it.

Monroe: He did less drawing; he didn't do quite as many drawings in his scenes. He'd give you one drawing, and then on his exposure sheet he'd be more descriptive, I think. And he'd learned an awful lot about timing, since I'd worked for him, and he'd proven himself as a damned good director. It was just more fun to work for him, and I guess I was better, too, so I enjoyed it more. I think we just learned to like each other, and it was very pleasant for the four years. I didn't quit on account of him, and he understands that.

Barrier: It sounds like your personal relationship had really changed more than his actual methods of direction.

Monroe: I think that's probably a good way to look at it.

[Posted June 7, 2012; corrected, June 8, 2012, and June 22, 2015]