INTERVIEWS

Robert McKimson

An Interview by Michael Barrier

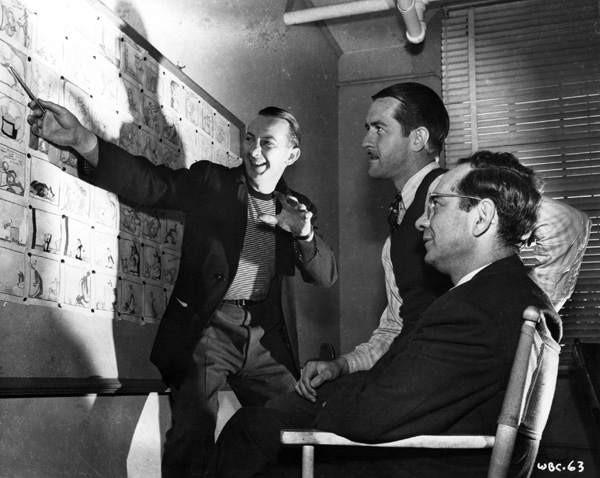

| Warren Foster poses in front of the storyboard for The Mouse-merized Cat (1946), one of the first cartoons directed by Bob McKimson. Seated in front of McKimson is Edward Selzer, who succeeded Leon Schlesinger as the producer of the Warner Bros. cartoons in 1944. The photo was published in the Warner Club News, the house organ for Warner Bros. employees, for April 1945. |

Robert Porter McKimson was one of the principal creators of the Warner Bros. cartoons, first as the studio's most imposing animator and then as a long-tenured director. Such enduring characters as Foghorn Leghorn and the Tasmanian Devil first appeared in his cartoons, and he was critically important in the development of Bugs Bunny.

Bob McKimson was born in Denver, Colorado, on October 13, 1910. In autobiographical notes written in 1944, when he was promoted from animator to director, he said that his "schooling consisted of a start in a small country schoolhouse—which contained eight elementary grades in one large room, then on through five years in a small town called Wray, Colorado, where my father owned the weekly newspaper." The McKimson family moved briefly to Los Angeles in 1921, then back to Colorado, and then to Texas, buying and operating a newspaper in each place. Finally, in 1926, McKimson's parents sold their newspaper in Canadian, Texas, a Panhandle town, and moved back to Los Angeles, this time for good.

"My father taught my two brothers and myself the newspaper and printing business from the ground up," McKimson wrote in 1944. "My mother, being an artist, taught each of us everything she knew about drawing from the time we could hold a pencil. Before coming to California my only artistic endeavors were newspaper cartoons, drawings etc. for state and county fairs, and drawing anything and everything for my own pleasure."

McKimson's first job in Los Angeles was as a linotype operator. "In the summer of 1929," he wrote, "I received a telepone call asking me if I would like to draw cartoons for the Walt Disney Studios. My old brother [Tom] had been working at the Disney studio for about two weeks at that time, so I started the following Monday morning." The story picks up from there in this interview.

McKimson's first job in Los Angeles was as a linotype operator. "In the summer of 1929," he wrote, "I received a telepone call asking me if I would like to draw cartoons for the Walt Disney Studios. My old brother [Tom] had been working at the Disney studio for about two weeks at that time, so I started the following Monday morning." The story picks up from there in this interview.

(Neither Bob nor Tom McKimson shows up on the list of early Disney employees that the Disney archivist Dave Smith compiled years ago, but there's no reason to doubt that they worked there; Dick Lundy, the Disney animator whom Bob assisted, remembered both of them very well.)

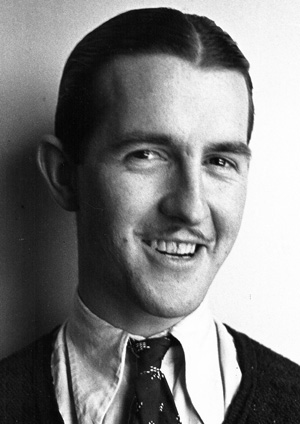

I interviewed Bob McKimson on May 28, 1971, during my second trip to California. The interview took place at his home on Roxbury Drive in Beverly Hills, where he lived alone; his wife, Viola, had died in 1963. My wife, Phyllis, took the adjacent snapshot of Bob and me just after the interview; I believe the portrait, which Bob painted, is of his son, Robert Jr., but my notes don't confirm that.

As always when I review one of my interview transcripts, I'm reminded of questions I should have asked—about Friz Freleng as a director in the 1930s, for example, or about McKimson himself as a polo player on the Harman-Ising team early in that decade. And I'd like to know more about that aunt who hung out with movie stars! But I think what's here is more than adequate to give some sense of how secure and self-confident Bob McKimson was, as a person and especially as an animator and director.

Bob McKimson collapsed and died unexpectedly on September 17, 1977. He was still working, directing a film for DePatie-Freleng, when he died.

The interview that follows reproduces the complete transcript, incorporating a few corrections that Bob made when he reviewed it in 1974, but restoring deletions that he made not for the sake of accuracy but to avoid giving offense to former colleagues. Since all the persons involved are no longer alive, such considerations are no longer controlling.

I resisted the temptation to tinker with a few passages that seem to reflect some confusion on my part and possibly Bob's, like the opening exchange where we seem to be talking about different kinds of "units." But I realized, in reading our exchange about the Bugs Bunny model sheets reproduced with the Bob Clampett interview in Funnyworld No. 12—published in 1970, less than a year before I interviewed Bob McKimson—that it might be helpful to reproduce all seven in the succession of model sheets that led up to McKimson's definitive 1943 model sheet. So, I've added a sidebar reproducing those sheets, with accompanying text taken mostly from my book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. You can go to that sidebar, "Remodeling the Rabbit," by clicking on this link. (The Clampett interview is also available, at this link, but without reproductions of the two model sheets in question.)

On to the interview.

Barrier: I know what your brother Tom is doing now [he was then the art editor at Western Publishing's Hollywood office], but what is your [younger] brother Chuck doing?

McKimson:Chuck is with Pacific Title; he has his own animation unit. Chuck worked with me up until 1953, and Tom worked with me up until 1944. When I started directing, Tom went with Western Publishing.

Barrier: Were all three of you ever in the same unit?

McKimson: Yes, at one time. Tom had gone when I started directing, but Chuck animated for me, so in the credits you'll see his name as an animator. Before that, when I was animating, I was with Bob Clampett, and Tom was a layout man for Bob Clampett, and also an animator for him.

Barrier: How did you get your start at the Disney studio?

McKimson: There were probably not over thirty people in the whole studio [at that time]. My older brother Tom and I started at the studio within two weeks of each other. I was the assistant—they just called them inbetweeners then—to Dick Lundy, and Tom was inbetweener to Norm Ferguson. They had nine animators there, and each of them had an assistant. So there were eighteen, out of about thirty people. Walt would okay every test himself.

When I first started doing little bits of animation, the first thing I did was a walk on Mickey Mouse. I had to animate this Mickey Mouse walk three or four times; the walk was fine, except the buttons on his pants rode up and down a little too much, or not quite enough—something like that. He was that careful even in those days.

I came just after Carl Stalling and Ub Iwerks had left. My brother and I didn't stay too long there, because we were supporting the whole family; my dad came out here from Texas, and lost almost fifty thousand dollars inside of about a year's time. So Tom and I had to support two brothers and two sisters; we needed money. Romer Grey, Zane Grey's son, decided that he was going to start a cartoon studio, and he offered us eighty bucks a week. That was big money, to us, in those days especially since we were making twenty-five at Disney's. We started at eighteen [dollars], and inside of six months we were up to twenty-five, and we felt we were doing fine. When we told him [Disney] we were going to quit, he offered to double our salaries, but that still wasn't enough. That's about as far as he could have gone.

We animated then three or four pictures for Romer Grey, and Romer decided to spend more money on having a good time, hunting trips and things like that, and left everybody high and dry. Tom and I went over to Harman-Ising at that time; we were with [Harman-Ising] until the summer of 1933, and then Schlesinger opened up on the Sunset lot and Harman-Ising closed down. Schlesinger gave me a good offer and I went over there. My brother stayed with Harman-Ising. So, from 1930, until they closed up, I was with the Warner release. Friz [Freleng] was there about the same time, but he had two years out with MGM.

We animated then three or four pictures for Romer Grey, and Romer decided to spend more money on having a good time, hunting trips and things like that, and left everybody high and dry. Tom and I went over to Harman-Ising at that time; we were with [Harman-Ising] until the summer of 1933, and then Schlesinger opened up on the Sunset lot and Harman-Ising closed down. Schlesinger gave me a good offer and I went over there. My brother stayed with Harman-Ising. So, from 1930, until they closed up, I was with the Warner release. Friz [Freleng] was there about the same time, but he had two years out with MGM.

Barrier: Were you already classed as an animator by the time you went to Harman-Ising. Had you become one while you were at Disney's?

McKimson: Yes. There's a real strange story. In 1932, I was animating, doing about the same amount as every animator, twenty, twenty-five, thirty feet a week, at the tops. I had an auto accident and [got thrown out of the car], and pinched a couple of nerves in my neck. I got out of the hospital after a couple of weeks and went back to work, and all of a sudden, I could do fifty, sixty, seventy, eighty feet a week, and it was easy. It was a strange thing.

I went to school to learn more about drawing; I was always fascinated with portraiture and anatomy. I got so that I could visualize things; someone would describe something to me, I would visualize it, and Slow it down to slow motion, and then just draw it like that. It always fascinated people to see me do these things. I could start from the shoe and build him up, or I could start from the top and build him on down, or the side, anyplace, but it always came out the same. It was a strange thing, even to me. For ten years, I averaged fifty-five feet a week. Even in the union, they wouldn't classify me with anyone else, because nobody else could do the same things that I did.

Barrier: Did they have any medical explanation for this?

McKimson: None of the doctors could give me any explanation for it. They said I probably jarred something loose in my brain. It was very simple for me to do this; it wasn't any work. At Harman-Ising one day, I'd been up to two or three the night before. I'd gotten so that I could sleep on one arm, and I would sleep about half the day, and still put out that much, and never leave more than three in-betweens anyplace, for anyone: everything else was all cleaned up.

One day the studio manager called me in the office and said, "Bob, there seems to be something wrong with you." I said, "What do you mean, my footage is all right." He said, "Oh, fine, great." I said, "The quality's all right, isn't it?" He said, "Oh, yes, great. I just thought something was wrong with you because you sleep so much." I said, "Well, it's mostly because I don't go to bed very early." He said, "I was worried about you, not about your work." That was Ray Katz.

Barrier: When you were at Harman-Ising, how were they organized as far as the direction and animation were concerned?

McKimson: Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising were actually co-directors, and Friz Freleng was sort of a head animator. In the last few months, Friz did some of the directing. But [he really got started directing] after he went over to Schlesinger's.

Barrier: When you went to Schlesinger's, how large a staff did he have?

McKimson: Jack King was there, and Earl Duvall, and Tom Palmer, and Friz. There were actually four directors to start off with; well, it started off with one, really, Tom Palmer, and then by the time I got there, after a few months, Tom Palmer was gone. He was one of the guys who was over at Disney's when I was there; I don't know what ever happened to him. Earl Duvall made a couple of pictures, and then Friz came in, and directed constantly from then on. Tex Avery was about the next one to come in. That was around 1935.

In 1937, Schlesinger offered me a direction spot, and I told him I didn't particularly want it, because I would rather learn a little more about making pictures, before I took over the direction spot. It was right about that time he asked me how I thought Chuck Jones would do in that spot, and I said I thought he would do fine. Chuck doesn't even know this.

Barrier: Chuck says that Henry Binder picked him.

McKimson: Binder wasn't even in the picture, really. He was Schlesinger's secretary. Later on, he got in the picture, after 1938, when we moved from the middle of the studio [the Warner lot on Sunset Boulevard] to the bigger studio [the Vitaphone building at the corner of Fernwood and Van Ness]. These are things that even Chuck doesn't know. There are so many things, and each man knows a little bit about some things. Sometimes they can blow these things up into such proportions that somebody's going to get stepped on. I've been stepped on an awful lot.

One thing that was such a happy proposition, among Friz and Chuck and I, was that we each had a little bit different way of going about things. It was a healthy competition, because one time one would do something in a picture that another one would pick up and use in his picture. It worked that way all the way around, and nobody worried about it at the time, but later on, they got to taking credit for a lot of things that didn't belong to them. Different people got too big for their britches, so they didn't want to give anybody else any credit. The creation of all of the characters took more than one man. One time, Chuck Jones had just got back from Denver, and he was talking to us about the square dance group he went with, and he said, "I've taken over Denver as my area as creator of Bugs Bunny." I said, "You can't do that, that's my town, I was born in Denver!" He said, "Well, I've got it now."

Barrier: When you started working at the Schlesinger studio, were you assigned to a particular director, or did you shift from one to another?

McKimson: At Harman-Ising, at times you'd work with Rudy and at times you'd work with Hugh. After we got over to the Sunset lot with Schlesinger, I worked most of the time with Friz, but I did work with Jack King. I worked with almost all of them, even Earl Duvall.

Barrier: Eventually, of course, you worked in Avery's unit. When did you actually settle down as a member of his unit? It wasn't just after he came, was it?

McKimson: No, I worked with Chuck, and then I went in as the head of all animation, working with all units, and so I had to okay all the animation all over the whole place. Then, right after that, I went to work with Avery, at the tail end of '38 or the first part of '39. That was when Bugs Bunny was created. A lot ofpeople give Bugs Hardaway credit for creating Bugs Bunny, but really, there's no reason for it, because his bunny was closer to Oswald the Rabbit than to Bugs Bunny. It wasn't the same, so actually, there's no reason to give any credit to him. The name was on the model sheet, "Bugs' Bunny." When I went with Tex, he had me draw the characters, the model sheets; all the model sheets in that first one were mine. Clampett said there was one that Bob Givens did, but Bob Givens' style was completely different from mine. The feet, for instance—nobody drew them like I did.

Barrier: Now, there were two in Funnyworld No. 12—a 1943 model sheet that Clampett said you drew, and an earlier model sheet that he attributed to Bob Givens.

McKimson: I drew all of them; Bob Givens was later, really. His was maybe '43, but mine was in '39, that first one. Both of them that were in there [in Funnyworld No. 12] were mine. I don't know whether Clampett even has one of Givens' model sheets.

Barrier: He has one he showed me this week, of the tortoises in Tortoise Beats hare, Tex's second Bugs Bunny. That was about a year after A Wild Hare, I think.

McKimson: It was probably at least a year. You'll notice in this thing [McKimson's autobiographical sketch from the 1940s], Tex didn't want to make another Bugs Bunny after the first one. Ray Katz told him that he'd like to have him make another one, and he said, "Okay, I’ll make this one for McKimp." He always called me "McKimp." He knew that I liked to animate on [Bugs], and liked to work with him, and so that was how come he made even the second one.

Barrier: I’ve noticed that in All This and Rabbit Stew, the last of Tex's four Bugs Bunny cartoons, the animation is getting wilder, and more like Tex's MGM stuff. Bugs flies apart at one point.

McKimson: This was one of those things that I didn't have much control over, because I was animating at the time. Both Tex and Clampett liked to over-animate; they liked everything over-animated. If you'd go like this [making a restrained gesture], they'd want you to go like this [making an extravagant gesture]. Then, gradually, after Clampett left, we started calming down, and underplaying a lot of these things. Finally, it got a little too underplayed, really, so that Bugs almost flattened out to a nothing. Whether he likes it or not, this was half Chuck's idea, this underplaying, and it got so it was so underplayed, [Bugs] didn't have any personality. Then we had to get back into the pixie thing again, where Bugs was Bugs. These are things that develop with a character, and they go back and forth.

Barrier: You said you were supervising all the animation at the studio ... when you went with Avery, did you still supervise as well?

McKimson: Most of the time, yes.

Barrier: What did your duties involve?

McKimson: That was the crazy thing about it. They expected me to do about twenty feet a week, and still oversee all the animation, all over the studio. This was what they thought of me, as far as my ability was concerned; but that was an awful lot to ask. But that's what I was doing, up until Clampett came in, when Tex left. Then I went with Clampett full time, and the rest of the units just did their own thing.

Barrier: What are some of your impressions of Clampett and Avery as directors? You've mentioned their wildness and their over-animating...

McKimson: I think Tex started a whole lot of new trends in animation. Speed stuff—a character going from here to here in no drawings. None of us ever even thought about doing a thing like that. But he tried it out, and it worked. He got what we called "zip" into cartoons, and a real fast pace. That's one thing he did that no one argues with.

As far as Clampett is concerned, he started characters like Tweety, and Sylvester...you could almost tell, from the characters themselves, whether Clampett had anything to do with them. He was sort of an oddball, which was great on these things. Like Tweety; nobody talked that kind of talk [imitating Tweety] except Clampett. Clampett started at Harman-Ising, too, a little before I did; but he was an assistant, and I was an animator. It took him a while to get up where I was. But then he came over to Schlesinger's, and he animated for a while, and then he got into direction, and I think that he did a lot of good things. But when you look back on it, it wasn't a very long time. He left very shortly after I became a director [in 1944].

Barrier: When you finally did become a director, what led to that decision?

McKimson: I felt that I could do the job as well as anyone else there, and I had the proper experience, so when Tash [Frank Tashlin] left, everybody and his brother was saying, "I'm going to take Tash's place," so I went to Eddie Selzer and asked him if Tash was leaving. He said yes, and I said it was about time that I took it over. He said, "Fine, do you want it?" I said sure, and he said, "Well, somebody told me you didn't want it." I said, "Well, certainly." That's all there was to it, and I took it over.

Barrier: How did you make the transition, in your own approach to your work?

McKimson: There wasn't much transition there, because working with Clampett, I had to do practically everything that a director had to do, most of the time, because he was out doing something else, or he'd just had it. He'd come in and tell me to time it out, and fix it up, and lay it out, and give it to the animators. It was very simple to do, that way. I actually almost just stepped into it, because when he found out that I could do these things... I don't blame him, I would have done the same thing, if I'd had someone who could do it. But so many times, a director is so burdened down with so many little detail things, that if somebody can time your stuff out, or lay it out for animators, it gives the director more time to do something else that is more important to the picture.

Barrier: Like the story, for example; evidently Clampett was very attentive to that aspect.

McKimson: This is what is strange. Everyone has a different story on this, but there was a director, and he had his own story man, his own layout man, his own background man, his own animators. A complete unit. And we all worked the same way. We would get together with our story man, and if you had any ideas that you wanted to give to him, you'd give them to him. Otherwise, he would give you a flock of ideas, and if you happened to like them, fine. If you didn't, you'd kick ideas around until you did come up with an idea. Then, for five weeks they would work on this, with the director—back and forth, until they got their storyboard up. Then, most of the time, we would have what we called "jam sessions," and we would have all the directors and all the story men, and some others, too, and we would rip the thing apart, and throw new gags at it, and twist gags around, until we felt we had a real good story. Now, every cartoon was done the same way. It was only after that that the director took it, and then he would mold it in his own particular way.

Barrier: Did these jam sessions go on continuously, throughout your career at Warners, from the time you became a director?

McKimson: Yes, that's right. It was a very good way of working, because you got so that you didn't get the same old gags all the time, you got twists on gags. It made it a lot more interesting, and it kept the thing modernized.

Barrier: Which was your first cartoon?

McKimson: It was called Daffy Doodles.

Barrier: How much work had been done on that when you took over Tashlin's unit?

McKimson: Warren Foster was my story man, and we worked that thing out together when I first went in.

Barrier: How many cartoons would a Warner unit have going at once, in different stages of production?

McKimson: I figured that out one time, and I figured that I had to know every detail of about fourteen different cartoons, at one time. That's from the time you start talking about story until you see them on the screen. Each [unit] turned out ten a year.

Barrier: So you were dealing at any given time with about a year and a half's cartoons. So there must have been some Tashlin cartoons that you finished up.

McKimson: There were probably some that had to be finished up, yes, but there were only a few of them.

Barrier: The first Bugs Bunny cartoon you made seems to have been Acrobatty Bunny.

McKimson: That was one that showed up at the Academy [?]—about the fourth picture I made was Walky Talky Hawky, and really, that one should have won the Academy Award, because that was a funny cartoon. Friz had a cartoon called Rhapsody Rabbit, and MGM had The Cat Concerto; they were exactly the same music, the same story, and everything else. Quimby offered to pull his out if Eddie Selzer would pull his out. Eddie wouldn't pull it out, and it wasn't even nominated. [That left] Walky Talky Hawky and Cat Concerto. Walky Talky Hawky got a much bigger audience reaction; in fact, it got a terrific audience reaction. But it didn't get the award. At that time, there was bloc voting, and MGM had more members than we did.

Barrier: Was that the first Foghorn Leghorn cartoon?

McKimson: That was it.

Barrier: Can you tell me how Foghorn came into being? He was patterned somewhat after Senator Claghorn, wasn't he?

McKimson: I'll tell you what happened there. Warren Foster, my story man at the time, had a rooster story—an idea for one—and we started kicking it around, and all of sudden, I told him, "I was listening to the radio the other night, and there was this Senator Claghorn," and I said, "He took his type of delivery, and so forth, from the old sheriff in the old Blue Monday Jamboree." This business of saying, "I say there, son" [imitating the voice) was because the old sheriff was deaf, and he didn't think people could hear. He was deaf himself, and he thought he wasn't coming over. I told Warren about it, and he was nuts about the idea. We sort of merged the two ideas of the old sheriff and Senator Claghorn, and put them on to Foghorn Leghorn.

Barrier: So you told Mel Blanc the kind of voice you wanted...

McKimson: Well, on the first one, we had somebody else do it, and it didn't work out too well. I didn't think that Mel could do it, but when we showed Mel what we wanted, he went ahead and did it, and did a real good job of it. But it wasn't copied right after Senator Claghorn. Have you ever heard of Al Pierce and His Gang? That was about the same time as Blue Monday Jamboree. Those were two very funny shows. Guys came out of that like—oh, I think Cliff Arquette was one of them. They had an awful lot of real good comics at that time; I think even Fred Allen was on it some of the time.

Barrier: That's something that interests me ... how all of you at Warners used material from radio and TV and anything else you could use. For example, you made the cartoons based on Jackie Gleason's Honeymooners. It always interested me that Warners would do this, while the other studios seemed to have a taboo against using anything that wouldn't be understood in Afghanistan.

McKimson: Well, I thought these things were funny to anybody, really. The Mouse That Jack Built, the one with Jack Benny and his group...he asked me to make it [after] he saw these "Honeymousers." On the "Honeymousers," when Jackie Gleason heard about these cartoons being out, he said, "Now wait a minute, I don't know if I want you to make these things or not. You get that picture down here, and I want to see it.” He had his whole group down there, and they started running it, and they said that inside of about two seconds, he was in the aisles, just laughing himself silly. He said, "Boy, leave this alone, make as many of 'em as you want.” That was what Jack Benny saw, and so he wanted one. He wanted to do the voices for nothing, but we had to pay him scale. When we gave Rochester his check, he said, "Just slip it under the door." A wonderful bunch of people.

Barrier: One other cartoon you've made that intrigues me is called Kiddin' the Kitten; it has a large tomcat character who looks like a caricature of someone, but I can't figure out who it could be.

McKimson: He really wasn't a caricature of anybody, but he was a W. C. Fields type. But that's about all you can say about him.

Barrier: What governed your use of characters? How did you decide to repeat a character? I guess you got back some audience response, but did you have your own. antennae that told you…

McKimson: Usually we would try to catch them in theaters, and see how the audiences went for them. I made one cartoon, The Hole Idea, that I thought was one of the cleverest stories I'd ever seen. It got an award from the University of Wisconsin; it was one of the ten best short subjects of that year, and the only cartoon. Yet Eddie Selzer wouldn't put it up for an Academy; he wanted to put up a couple of others. He put up the others, and I don't think they got anything. He didn't want to put up my Hillbilly Hare, the square-dance picture; he put up one of Friz's and one of Chuck 's, and neither one of them was even nominated. Then he said, "Well, I guess I should have put up Hillbilly Hare." I got left out of the Academy stuff quite a bit, for political reasons.

Barrier: To hear Friz and Chuck talk, they seem to have regarded you—perhaps because you were the junior director—as sort of the third wheel. Did you have the feeling that you were fighting against the odds?

McKimson: Oh, man, I'll tell you, I've got scars all over my back. They made it a point to hold me—or anybody else—down, so that they could be on top. This didn't bother me, really. It bothered other people more than it bothered me. We all worked the same; there was no different way of working, except in the actual direction of the pictures. Up to the point where the direction started, after the story and everything, we all worked exactly the same. But they would have you believe that they were the only ones who were working, by themselves, never giving credit to their story men. The story men were very, very valuable. Chuck never gave Mike [Maltese] the credit he deserved. Mike had the idea, in the first place, of the Road Runner and the Coyote, and Pepe le Pew. These were his original ideas. There is one thing: there is no creation until the director takes it and makes a picture of it. But these ideas [from the story men] are invaluable.

Barrier: How much did you rely on your story man? How many ideas did you suggest to your story man, and how many did he have?

McKimson: It would be very hard to say. My story man, once in a while, would come up with maybe eight or ten ideas, and I might find something in one of them that sparked [another] idea, and so we would go to work on the idea. Before we got through, we'd have a story. Then, sometimes, I'd have an idea, and I'd tell it to him, and let him work on it, and then we would work on it together to get it in shape. A director and a story man had to work together, because with a story man, [writing a story] was his whole business; the director had everything to think about—the story, the direction, the animation, the layout, and the background. And even the inking and painting.

Barrier: How did your own background as an animator come into play when, say, you were supervising the animators in your unit?

McKimson: It [worked] against me, in a way. The boss—Selzer, for instance—would say, "Well, you can handle so-and-so, maybe he's not so good, but I’ll give this better animator to Friz or Chuck, and you take the worse one, because you can handle him." I was always being saddled with that type of man. I said one time that I had a unit of drunks and queers. I had a layout man—he was a very good layout man—who was a queer, and a background man at the same time who was a queer, and they were just at each other's throats all the time. So finally I had to get rid of the background man. I was always having drunks in there, but they did good work for me. They knew that I knew that I could just flip the thing through and tell whether there was a mistake.

I had one animator, who thought he was better than he was, and I'd just flip it through, and I'd say, well, this has got to be changed, it won't work this way. He said, "I think it will." I said, "All right, Rod [Scribner], you go and test this"—cheap negative testing—"and we'll run it on the movieola, and I'll show you what I mean exactly." He said, "All right, but I know it's right." Every three to six months, he'd come up with one of these things. So I'd just tell him to go ahead and shoot it. We'd put it on the movieola and run it through and through, on the loop; every time, he'd say, "Yeah, yeah, I see what you mean." And then the next time, he'd say, "Well, I think it's right." But that was the only way it worked against me. I had to take guys with a little less ability and try to make something out of them.

Barrier: Did the studio politics you mentioned play a role in the kind of men you were assigned?

McKimson: Yes. If I just didn't want him, period, I wouldn't have to take him, but there were some of them that were sort of borderline cases, and maybe someone you happened to like and didn't mind spending a little time with. You had to spend time with these guys.

Barrier: How many drawings would you do yourself in the course of preparing for a cartoon?

McKimson: I worked a lot like Chuck works. Chuck always has worked that way, making character layout drawings throughout a whole scene, and for every scene in a picture. Maybe two or three hundred drawings were made for a whole picture.

Barrier: Then the animators would work from these...

McKimson: That's right, so the whole picture would look almost the same; the characters would look the same throughout the picture. Friz had Hawley Pratt, who did the same thing that Chuck and I did. He laid out the characters.

Barrier: When you first started with Foghorn Leghorn, did you have any idea that he would be a continuing character?

McKimson: I thought that he was a good character, but, again, you have to wait until you get some reactions from the public. We always got good reactions from the public on Foghorn Leghorn.

Barrier: Did you have channels of communication [from the public] other than what you heard yourselves in the theaters? Did exhibitors request more cartoons of certain types?

McKimson: Not necessarily, no; but a lot of times Jack Warner would. He loved cartoons. The Tasmanian Devil, for instance...after I made the first one, Eddie Selzer said he didn't like it, and didn't want us to make any more. I was in the midst of making another one at that time, and so I finished it up. It must have been a year that we didn't make any, and all of a sudden Jack Warner said, "How come we don't have any more of these Tasmanian Devils?" Eddie Selzer said, "Oh, I thought he was an obnoxious character, and I told him not to make any more." He said, "To hell with that! Let's get going, we're getting letters all over the place here for that Tasmanian Devil. Let's get going and make some more." So I started making some more of them.

Barrier: A lot of the Warner cartoons—like your Foghorn Leghorn series and Tasmanian Devil series—take the same basic situation and work some changes on it. Was this something you set out to do, or did you just fall into this pattern?

McKimson: It's like any story there is—it's just a twist on another story. We did probably a dozen or so twists on "Little Red Riding Hood." Every one of them was funny, and every one of them was different. There are still dozens more ways of twisting the same story. using different characters, and so forth. Usually, what we tried to do was keep the same sort of overall plan on these stories that would be funny, basically. We tried to get the most humor out of it, and still have a good beginning, a good buildup, and a good ending.

Barrier: Bob Clampett mentioned to me that you had told him something about how Speedy Gonzales came to be.

McKimson: You'll get a lot of funny stories about this that aren't true. In this one picture that I made with Sylvester on a boat going to Mexico, he gets on the boat, and then there's this little mouse—a fast mouse. While we were talking, a fireman friend of mine—who is now retired and lives down in Yucca Valley… To me, he was one of the funniest men I ever knew in my life, and it had nothing to do with [his being] a fireman. When he'd tell a story, he could tell any story, and it'd be funny. He told this dirty little story about Speedy Gonzales, and I thought it was very funny, especially the way he told it. We were working on this story at the time, and so the next day I came in, and—Warren Foster was again my story man at that time—I said, "I've got a name for that little fast mouse: Speedy Gonzales." He said, "Speedy Gonzales?" I said, "Yeah, now listen to this," and I told him the dirty joke. He said, "Good, that's what it'll be." About a month or so ago, I was recording some stuff with Mel Blanc, and Mel Blanc was talking to somebody, and he said, "Yeah, I named Speedy Gonzales. I told these guys that joke, and they named him." Well, it was my character, and I know how it was developed. I didn't say anything; I let Mel go on thinking… He thinks he's the creator of Bugs Bunny, anyway. So many of the voices that Mel has, either Friz, Chuck, myself, Tex, or Clampett—one of the five of us—gave him the ideas of what to do in these things, and he had the larynx—the leather larynx—to do it.

Barrier: Was there ever a case when Mel had a voice that you did not have a character for, and you decided to make a character fit this voice?

McKimson: Sylvester was something like that. He had the juicy voice, you know. He's the closest, I would say, that Mel would come to having an original voice, and then fitting the character to it.

Barrier: Of course, Daffy Duck's voice is the same as Sylvester's voice, only sped, so I guess when Mel recorded, he sounded like Sylvester, and then you sped it up to sound like Daffy.

McKimson: That's right. Little Sylvester is my character, and so his lisp was more of a "th" sound than an "sth" sound; it's not juicy. It's small. everything was small. He was a very successful character.

Barrier: Didn't that series start just about the time Sylvester himself was emerging as a character? He was kind of unformed back in the middle forties…

McKimson: My brother Tom made the original character sketches on Sylvester, for Bob Clampett. It was shortly after that that Clampett left the studio, and so did my brother. Friz took over the character; he also took over Tweety at that time, too. Today, why, he's the creator of both of them, if you can believe him.

[McKimson was probably referring to the cat in Clampett's Birdy and the Beast (1944), the second cartoon with Tweety. That cat's black-and-white coloring is highly similar to Sylvester's, but otherwise the Clampett cat does not resemble Sylvester as he debuted in Freleng's Life with Feathers (1945). MB]

Barrier: What I'm working around to is how Mel's voice suggested Sylvester. Did the character appear, and then Mel's voice suggest itself for the character? Is that what happened?

McKimson: Probably. I really don't know too much about that, because I wasn't working on Sylvester at that time.

Barrier: On the way the characters were parceled out at Warner's…if you had decided, say, that you wanted to use Tweety in one of your cartoons, was there anything to stop you from doing this, or would it have been a breach of etiquette if you had done it?

McKimson: We each had our own characters, and we each did Bugs Bunnys—usually, we each had four Bugs Bunnys to do, a year. Daffys, Porkys, Elmer Fudds—these were all mixed up, among all of us. But Chuck did his Road Runner and Coyotes, and his Charlie Dogs...he had a lot of characters that just didn't catch on, except for maybe just a short while. Then with Friz, there was Tweety and Sylvester, that we just let him go ahead with, and Yosemite Sam, and Elmer Fudd most of the time, but we all used Elmer Fudd. We tried not to step on each other's toes as far as characters—certain main characters—were concerned. I wouldn't do any Road Runners, or Pepe le Pews, or Tweety and Sylvesters—well, I did do Sylvester, but no Tweety—or Yosemite Sams, and they wouldn't do any Foghorn Leghorns, or Little Sylvesters.

Barrier: But no one could have stopped you, though, if you had wanted to use someone else's character.

McKimson: No; in fact, I know Friz used my Little Sylvester in one picture, and I think he used Pepe le Pew in one picture. And, of course, Chuck used Sylvester, and so did I. I used little Henery Hawk; that was Chuck's character.

Barrier: Chuck had kind of discarded him, though...

McKimson: Oh, yeah. He never did anything with him, so I picked him up and used him with Foghorn Leghorn.

Barrier: You seemed in your first Bugs Bunnys to have retained a little of the wildness, the stretch and squash, that the Clampett Bugs Bunnys had.

McKimson: At first, because I was using the same animators, really. So, naturally, until I got them tamed down a little bit, they were still going overboard.

Barrier: I've noticed, from the credits, that the personnel of the various units switched around quite a bit in the Forties...did some men who were in Clampett's and Art Davis's unit switch over to you, because they were used to working with you?

McKimson: In some cases, yes, and in other cases, it was because Art Davis's unit was on for a while, and then it was off, entirely. They had to place those guys in other units. When I took over Tashlin's unit, most of the guys had worked with me before, in some of these other units. That's one reason so much of it looked quite a bit the same, because they were used to over-animating, and I had to calm them down.

Barrier: You had Rod Scribner in your unit, and he was, I guess, the wildest of the animators…

McKimson: He was the guy I was telling you about. After he started calming down more, he was a much better animator.

Barrier: During the fifties, the walls seem to have been closing in on all three units—sort of gathering clouds of doom. Did morale start sagging in the fifties? Did you feel that you were heading toward a dead end?

McKimson: Maybe toward the end of the Fifties. I would say it was after, oh, '57, '58, around in there someplace. About in there is when we almost saw the handwriting on the wall. They had tried to close us up every year since 1933, though. It was like Friz and I said one day, we had told people when we came in there it was a temporary job.

Barrier: How much actual, formal warning did you have that the place was going to be closed down?

McKimson: Probably not much over about two months. Of course, we had an idea, but really nothing concrete. When they did, I understand it wasn't over six months [before] they wished they hadn't done it.

Barrier: And you were there up until the day they closed.

McKimson: Yes.

Barrier: Did Friz leave before they actually closed? I've seen cartoons that were credited to people who were in his unit, like [Hawley] Pratt and [Gerry] Chiniquy.

McKimson: Hawley and Gerry and myself, really, directed the cartoon elements of this Limpet [The Incredible Mister Limpet], the feature with Don Knotts. I don't know where Chuck went, but Friz went over to Hanna-Barbera for a while, and so [they] had nothing to do with the Limpet thing. But I was still in there, and Hawley and Gerry.

Barrier: That was made before the Warner studio closed?

McKimson: Yes; it was finished up in 1963.

Barrier: I had been under the impression the studio closed in 1962.

McKimson: It was supposed to have, but it kept going until 1963, and we did a few things. In fact, I think that one cartoon I had, Bartholemew Versus the Wheel, was released in 1963.

Barrier: When Chuck and Friz left, did Pratt and Chiniquy finish up for them?

McKimson: That was sort of a mishmosh deal. They had a few things to do on these pictures that they had worked out with Friz before he left, and then the Limpet thing came along, so one was mixed in with another.

Barrier: So they were just sort of tidying up after Friz left…

McKimson: That's about what it was.

Barrier: What about Chuck's unit? The same thing?

McKimson: It had to be the same thing, because there was a certain amount of pictures that had to be finished up. Most of the guys who were in that unit did it themselves—Ken Harris, Benny Washam, whoever else was in there at the time, but particularly those two.

Barrier: There's a cartoon of yours that intrigues me, called Dog Tales; it's very much like the cartoons Tex Avery was doing ten years earlier—a string of gags on a single theme. This had not been done for years at Warners, and I was wondering what led you to do it.

McKimson: Every once in a while, I get the idea that I'd like to do something that was a little off of the beaten track. I know that both Friz and Chuck were so amazed when I [made] The Hole Idea, because it was strictly a stylized thing—stylized characters and everything. I even animated that one. I directed it and I animated it, all but about fifty feet of it. It was at a time when we were closing down, around 1953, on account of this 3-D dea1—we closed down for six months. At that time, we didn't even know whether we were ever going to open up again. I had this cartoon all set to be animated, and no animators; so I just animated it, myself. And that's the one that got more notice than almost any cartoon we ever had. I was always trying to do something a little different. It threw a lot of people, because of my background of fine art.

Barrier: Besides that film, did you do much animating after you became a director? Was The Hole Idea the exception to the rule?

McKimson: Yes. Usually, about once a year, I animate a commercial or something for my brother, Chuck, because he gets in a bind and he knows that I can do it. I've done it for years.

Barrier: Has your facility as an animator been impaired by not animating for long stretches?

McKimson: Not too much, for the simple reason that I have criticized the animators—my animators—all the time. When they finish a scene, they bring it into me, and if it's not right, I can tell them how to make it right. From that angle, you keep up on this stuff, all the time. You even keep up on color, and so forth, with your background man, because you're constantly criticizing your backgrounds and layouts. So you keep up with those things even though you don't do them too much yourself.

Barrier: What did you do after the Warner studio closed in '63? You went back there, to their new studio, after a while, didn't you?

McKimson: I directed the adventures of Magoo [the TV cartoons], Magoo as William Tell. Most of it was just commercials, and things like that. Then I worked with Freleng, two or three different times, on these Super-President deals. He and Dave DePatie were doing some Daffy Duck cartoons, when they were still at Warner's, and I directed those. Then I worked with Friz after they went out on Sepulveda, on the Super-President deal; I directed part of that series. Then I went with Bill Hendricks, at Warners; I was there for a year and a half or two years, I guess, then they closed us down again. Since then, it's just been commercials and titles and that sort of thing.

Barrier: Was it frustrating when you went to work on these different limited-animation series, since you had always worked in full animation?

McKimson: It's always very frustrating to work on this limited stuff. You can't really put a personality over, in limited animation. It's a sound thing, more than anything else—the sound will tell you what the personality is, and if the sound doesn't do it, then you're dead. With full animation, it's the body movements and things like that that are the personality to anybody. One person walks a certain way, or they move their hands a certain way, or they tilt their head a certain way. It gives them different personalities. That's what each of our characters had. You could listen to them talk, and they each had different voice mannerisms, but in order to really know what these characters were like, you had to see them.

Barrier: I would like your comments about the Clampett interview, because I’ve had complaints from people who refuse to specify what they don't like about it.

McKimson: The creation of Bugs Bunny, for instance…I don't give anybody any credit for creating Bugs Bunny except Tex Avery, for the character, and me, for the way he looks. I know both Chuck and Friz give Bugs Hardaway a lot of credit; it's like giving someone who worked at Terrytoons credit for Mickey Mouse.

Barrier: Clampett says that he believes you did all the finishing touches on the first real Bugs Bunny model sheet—really cleaned up the drawings and made them look good...but that the basic design, the rough sketches, were Givens's.

McKimson: Actually, I don't think Givens had anything to do with it until someplace in the forties, with Chuck Jones. For years, this one and this one [the two Bugs Bunny model sheets reproduced in Funnyworld No. 12] were the only ones around, and I did both of them.

Barrier: And that [the earlier of the two model sheets] preceded A Wild Hare? That's the one you did in 1939?

McKimson: This is the one that was done for...I guess it was A Wild Hare...that Tex did. This one (the earlier version] had little white tips on his ears, an oval-shaped head, and more of a Roman nose. By the time we made this one over here [the later model sheet], it [the nose] had started getting that little tiny break in the middle, there. Any character, over the years, becomes more refined; and you have to refine these different things.

Barrier: You said you and Rod Scribner did the original Tweety models?

McKimson: Yes.

Barrier: When you made these model sheets, would you be working from some rough sketch the director had given you? How would you go about making a model sheet?

McKimson: You play around with a lot of characters—just simple characters—until you get what is close to what [the director] wanted. And when you get what he wanted, then you go ahead and make a whole model sheet, in different poses.

Barrier: But he [using Avery and Bugs Bunny as an example] would say to you, "I want a rabbit character..."

McKimson: Yes, sort of a pixie character, and one that is workable. And so you go ahead and draw up several of them, and finally, when you get one that is close enough, then you can go ahead and do anything with it. It's just a matter of drawing so that he works, so that you can animate him and do anything you want to with him. But you see how much looser this one [the 1943 version] is than this one [the earlier version] was. We had been working with him for a while when this one [the 1943 version] was made, and we dissected him and found out what made him work.

Barrier: But you would not usually have even a rough sketch to work from when you first starting?

McKimson: Oh, no, you don't have anything, really.

Barrier: At what point, when you were working on a story with a new character, would you want a model sheet prepared? After your story was prepared? I've wondered, because I've seen model sheets— like those of Chuck's in Funnyworld No. 13—that have poses that are used in the cartoons themselves.

McKimson: Just before you got ready to animate. That's how come you'll find some of these action shots. A director lays out his whole picture, and he's got maybe two or three hundred character sketches: so he just lifts out a bunch of them and puts them on this model sheet. Bob [ClampettJ never was a very good artist; he drew funny stuff, but he wasn't really a very fine artist; neither is Friz. Chuck and I were the only ones who developed our art up to a fine point. Chuck has been going to art classes, off and on, for twenty years.

Barrier: You said, I believe, that he got the idea because you had been going to these classes.

McKimson: I think [so], because he was quite fascinated every time I would tell him things I had learned. A little after that, Disney started having Don Graham come over to Disney's. It was Don Graham's classes that Chuck was going to, down at Chouinard. I went for one semester to Don Graham's class. He spent most of his time talking to me; I was wondering what the other people in the class got out of it. I knew so much anatomy, and he was fascinated with the fact that we could talk anatomy, whereas these other students didn't know much anatomy, and so he'd tell them something and they didn't even know what he was talking about. But I knew exactly what he was talking about, so we could have quite a discussion. Even during rest periods, he’d come up, and we'd talk. He was interesting; I learned quite a bit from Don.

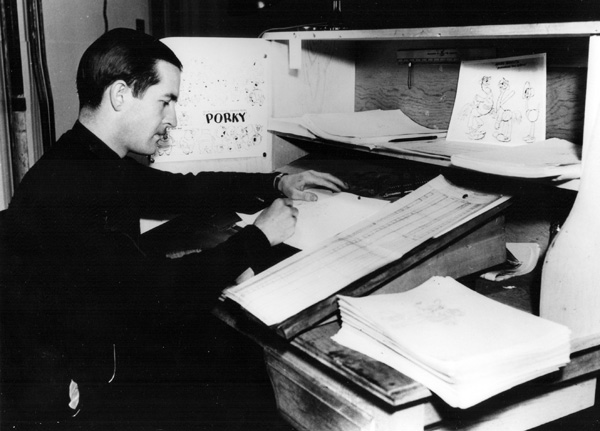

| McKimson at his animation desk, circa 1936, when he was animating for Friz Freleng. The model sheet at the right is for Boulevardier from the Bronx, directed by Freleng and released in October 1936. |

Barrier: You mentioned [in McKimson's autobiographical notes] that you animated Porky Pig's first scene in I Haven't Got a Hat.

McKimson: I was animating for Friz at the time, and I animated that first scene of Porky. When the public saw the picture, they got the biggest wallop out of this stuttering pig, and so we decided to make a character out of him. He changed around quite a bit, too, from little head and big body to bigger head and smaller body, and so forth. He went through the same changes that all the characters went through.

Barrier: But you don't know how Porky evolved in the story sessions…

McKimson: No, I don't. I wasn't involved in that part of it at that time.

Barrier: You mentioned those Romer Grey cartoons, and we saw that illustration of that character—what was the name?

McKimson: Binko—Binko the Cub.

Barrier: Was he much of a character?

McKimson: Just about like Bosko—not much of a character.

Barrier: Just a figure to run around and do tricks?

McKimson: That's about it.

Barrier: How exactly did you get your job at Disney's?

McKimson: My aunt, who lived in Denver, used to come out here quite often, and she hobnobbed with all the movie stars, and one night she was at a party, and Walt Disney was at the party. She was introduced to him, and she said, "I've got a couple of nephews who are pretty good artists,” and he said, "Tell them to get over to my studio and I'll give 'em a job." The next Monday morning, Tom went over. I was working on another job at the time. Tom got the job, and two weeks later, I was finished with my other job, and I went over, and I got on.

In those early days, everything was fun; that's why all of the cartoons came out funny, I think. Our story department, for instance; there were three of them [story men], most of the time. They had these different hats and coats, and things like that…spears, and old blunderbusses…all sorts of things like that. They'd go marching around the halls, and in the meantime, they were working on stories.

I noticed that Chuck mentioned about Schlesinger sort of lisping [in Funnyworld No. 13]. Almost every Monday morning, he'd stick his head in the story room, and say, "Well, boys, what are you working on today?" [imitating Schlesinger's voice] They'd say, oh, "A farm picture, with incidental gags." "Good, good, keep it up, keep it up." And he'd go on down the hall. The next Monday morning: "Well, boys, what are you working on today?" "A farm picture, with incidental gags." "Good, good." The same thing every time.

A lot of people may run down old Schlesinger, but he said something that I think is quite true: that he got a bunch of men together who were good in different lines, and together they made something spectacular out of what could have been just a blah thing. He always prided himself on getting the best people he could get to work for him; and then, he said, put them on their own, and leave them alone, and they'll put out good pictures. And we did.

Now Selzer, he tried to get in the story area; and actually, he didn't know anything about story. We had to keep working out ways to keep him out of it, because he was the boss. He was strictly a businessman, and if you weren't at your desk drawing, you were loafing—which is not true in our business, at all. Like these guys wandering around with these funny hats on...they were still working. They'd get ideas when they'd do things like this.

Barrier: Of the animators and the other people who have worked for you, are there any you remember with particular respect?

McKimson: There were several I trained myself; one was Ben Washam. He's one who'll tell you right away that I was the one who trained him. He's one of the best animators in Hollywood.

Barrier: When was this? I didn't realize that you and he had ever worked together.

McKimson: This was in 1938, when I was working with Chuck.

Barrier: When you were with Chuck, didn't you animate on Elmer's Pet Rabbit, with the first, Hardaway-Dalton Bugs Bunny? You were given screen credit [actually, the screen credit was for Elmer's Candid Camera, also with the early Bugs].

McKimson: I don't really remember if I did or not. [A brief discussion of the chronology of the early Bugs Bunny cartoons followed, leading up to mention by Barrier of Clampett's first Bugs cartoon, Wabbit Twouble.] They wouldn't let Clampett do a Bugs Bunny until I started working with him. Then they said that as long as I was working with him, they'd let him do it.

Barrier: Of course, he was directing only black and whites up until he took over Avery's unit, isn't that right?

McKimson: I think so, yes. He was working on what they called the Ray Katz unit. Ray Katz had a unit in the middle of the block, and we were over on the edge of it. Schlesinger was trying to get more pictures, that was the idea. so he had this extra unit. Both Bob Clampett and Chuck Jones were working with the Katz unit. [This was] in addition to the three units that were over where we were.

Barrier: Was there any sort of pecking order at the studio, so that the guys who were making black-and-white cartoons were below the guys who were making color cartoons?

McKimson: In a way, yes. This Katz unit over there, they had a name they called them...it was sort of an outsider's bunch, for a while, at least. They were doing the cheaper cartoons, all in black and white, and we were doing the color cartoons. We were supposed to be better; we really had the better workmen, all the way through, with more experience, and so forth. I'm trying to think of the name they called this unit…

Barrier: Clampett mentioned "Termite Terrace."

McKimson: That's it.

I remember the first time I ever met Chuck, I was working over at Romer Grey's. Chuck came in there one night when we were working. I reached over—I had the paper on the side, like this—to sharpen a pencil, you know how high you go, like this, to sharpen a pencil, [and] he said, "Do that again." So I did it again, and he said, "That's something, he's sharpening a pencil that way." That was the first time I ever met Chuck; he was working on Flip the Frog, for Ub Iwerks.

Barrier: What had brought him over to Romer Grey's?

McKimson: I don't know, he came over there with somebody.

Barrier: Do you have any memories associated with a cartoon called A Horsefly Fleas?

McKimson: Actually, that was one that Clampett first did, and I made a sequel to it. That was a Clampett creation, this flea. This was another one that Eddie Selzer didn't like, because he thought it was distasteful. He just didn't like the idea of the flea. It was such a square idea of humor that he had. We did pictures in spite of him, rather than because of him. And yet at times, he was as good an audience as you would want.

Barrier: Getting back to the animators you remember...

McKimson: Another one was Ken Harris. Phil Monroe was another. All of these guys had a flair for animation, for movement, for humor. They could do funny things with the characters, and they talked about them in funny ways. Other guys could move things around all right, but they lacked this one little spark of moving them in a funny way.

Over the years, I went through an awful lot of animators. Some of them I'd keep for a while, and then they'd quit and go to work somewhere else; some of them you'd just get up to a certain point, where you really thought you had them going good, and then they'd suddenly want to quit and go somewhere else for more money. At our place, we had a tough time getting more money for them, at the time. So we just had to let them go. In some cases, they did very, very well. Phil Monroe, now, for the last eight or ten years, he's been one of the top agency men, through Leo Burnett. He's a producer out here now. He was one of these people who was better, really, in telling other people what to do, and how to do these things, than doing them themselves. He made quite a career out of it, and he's done very well.

Barrier: Was Warren Foster your story man throughout your career as a director at Warner's?

McKimson: No; he was my story man from 1944 until '47, '48, around in there someplace. Then, through a few political maneuvers, Friz got him, and I took Friz's story man, Tedd Pierce. Tedd had a problem—the bottle. At one time, Tedd was one of the best story men in the business, but he got on the bottle so heavy that he just couldn't keep it up. Finally, he had to retire. But Mike Maltese, he was story man for Chuck almost all the time that Chuck directed.

Barrier: Except when he went to Lantz...

McKimson: He went [to Lantz] in 1953, when we closed it down, then he went back with Chuck when we opened up.

Barrier: Getting back to Bob Clampett, Friz Freleng told me that Clampett had been taken off the main characters because of his "bad taste."

McKimson: There was one thing that Clampett always did do. He always wanted to try to get by with something. It was an oddball quirk that really made a lot of his cartoons very funny; but it could get him in trouble. He'd do things that would hurt; some guy would fall into a meatgrinder, or something like that, and somebody'd come along and grind him up. These are things that can hurt while you see them.

Barrier: Tex Avery has been accused of being the same kind of director.

McKimson: Yes, but not nearly so much as Clampett. One thing that Clampett was always trying to do was get something that was a little sexy in a cartoon, and some of them went a little overboard. We had to just chop them, because you couldn't put things like that in a cartoon.

Barrier: Do you recall any specific examples?

McKimson: There was one where a hippopotamus fell on a Scottie; he had the hippopotamus like this, and the Scottie was right down here, and you can imagine what it looked like. He wanted to put that through, and he couldn't see why he couldn't, and there was hell there for quite a while. It looked like a naked woman, was what it looked like.

Barrier: Which cartoon was that?

McKimson: I don't know exactly; it was when I was working with him. [It was Baby Bottleneck.]

Barrier: I’ve heard varying stories about the reaction to Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs at the time it was made; do you recall any static while you were making it?

McKimson: No static while we were making it, no.

Barrier: Did you hear of any after you made it?

McKimson: I heard there were a lot of places that didn't want to show it. Friz made one about that time, too, [actually, a few years earlier, in 1937] called Clean Pastures, and they had to shelve that.

Barrier: You mean it wasn't shown?

McKimson: No, they had to shelve it. It was all about colored people.

[Clean Pastures was scheduled for release in May 1937, but its release was delayed unti October 1937 because the Production Code Administration objected to what it saw as a burlesque of religion. For details see page 342 of Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. MB]

Barrier: Friz made one called Goldilocks and the Jivin' Bears, which I understand was a Negro parody of the same kind.

McKimson: I don't remember if that was shelved or not, but I remember the picture being made.

Barrier: Do you recall any other instances of Clampett being put down for "bad taste"?

McKimson: There was always something, because he was always trying to put something through. Sometimes it could have been the way something was said, or something like that, but it was just on the edge of being risque. They'd tell him, "You can't do this," and he'd say, "Let's try it anyhow."

Barrier: Who would tell him this?

McKimson: All of us. Nine times out of ten it wouldn't work, because it wouldn't go through the Hays Office.

Barrier: What do you recall about the circumstances of Clampett's leaving the Warner studio? He wasn't dismissed because of this, was he?

McKimson: Oh, no. I don't really know too much about why he did leave. Of course, there was one time when Clampett would always do things that Schlesinger would tell him he couldn't do. He and Schlesinger were at swords' points quite a bit. But you could never get hold of Clampett; he was like a slippery eel. Schlesinger would call him into the office and get ready to bawl him out, and Clampett would say, "Wait just a minute, I'll be right back, I've got to go to the gentlemen's room." He'd leave, and he'd never come back. Maybe two days later, Schlesinger would meet him in the hall, and say, "Where the heck did you go?" [Clampett] would say, "What do you mean?" Clampett would do things like that that you just couldn't believe. I always liked Bob, and I always thought he had a pixie sense of humor. But he did do some things that were so oddball that you wondered how he ever stayed in as long as he did.

Barrier: You said he would be gone sometimes…where was he going?

McKimson: Who knows? I was supposed to be putting out over fifty feet a week, and sometimes it would be three or four days before I could find him. I didn't have anything to do. Then, when I'd get hold of him, he'd give me maybe a hundred, two hundred feet of [animation] to do. Then I'd have to beat my brains out to get my weekly footage out. You see, he didn't think of it from my angle, he always thought of it from his angle, doing what he wanted to do. He could con old Schlesinger into almost anything. Schlesinger would get so mad at him, and yet he liked him.

Barrier: Were there any of the Clampett cartoons that were in large proportion yours, because you handled the timing...

McKimson: Well, so many of them were; I couldn't tell you which ones. But I do know that is one reason I had no qualms about going into direction, because I was doing the same thing with Clampett, on maybe three out of every five pictures.

Barrier: You mentioned the poses you supplied…did Clampett supply that kind of drawing to his animators?

McKimson: No, he'd give one very, very rough drawing, and maybe some weird bunch of lines or something, and say, "This is what I want," and explain it, and then I'd have to go and make a set-up of the thing to give to the layout man, and then I'd have to lay out the characters. §

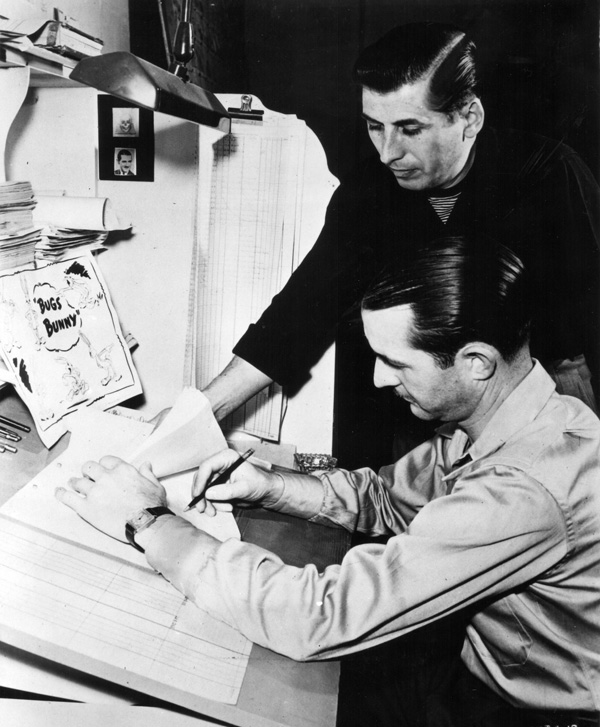

| McKimson and the animator Richard Bickenbach in a photo taken around the beginning of 1945, soon after McKimson succeeded Frank Tashlin as a Warner Bros. director. Like the photo of McKimson with Edward Selzer, above, it was published in the April 1945 issue of the Warner Club News. The Bugs Bunny "model sheet" was presumably added to the photo for decoration; there's no reason to believe that such sheets, prepared for merchandise licensees, played any part in production. |

[Posted February 16, 2011; revised, February 24, 2011]