INTERVIEWS

John Hubley

An interview by Michael Barrier

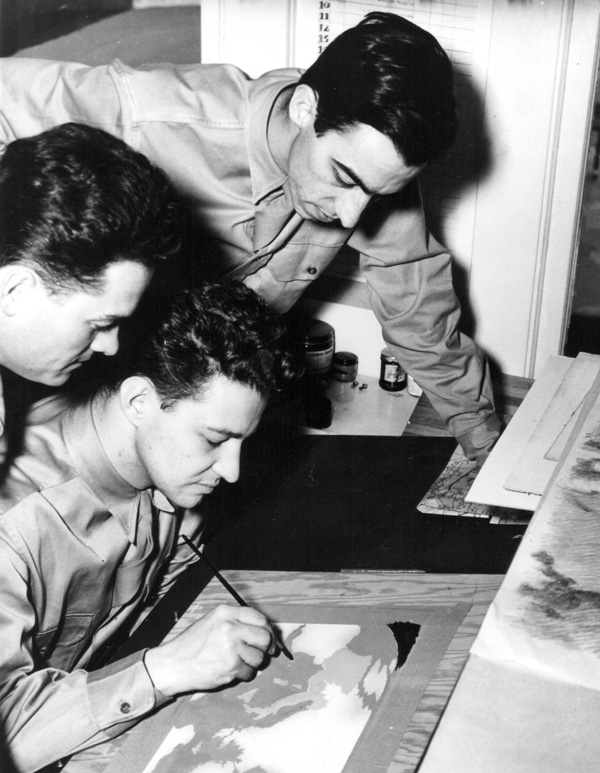

| John Hubley, at the board, pretends to work on a First Motion Picture Unit film while Joe Smith, a layout artist from MGM, at left, and Bob McIntosh, a background painter from Disney, pretend to be picking up pointers, in a photo from the early 1940s. Photo courtesy of Rudy Ising. |

I wrote to John Hubley in June 1975, asking for an interview that would be part of the research for my book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. I never heard directly from Hubley himself, but I have a file full of notes from phone conversations with his assistant Sue Bloland. Hubley was willing to talk with me, but finding a time when he would be free and I could be in New York, where Hubley had a studio on Park Avenue, proved to be very difficult ("Feb. looks chaotic," one note says). Setting a date for an interview got more urgent when the film magazine Millimeter asked me to write a piece about Hubley and his wife, Faith, and their joint filmmaking career, with a deadline of December 1, 1976. Hubley and I finally got together at Hubley's studio late on a Friday morning, November 26, 1976. Time was short, and not just because my interview deadline was looming—Hubley had another commitment, so we had only an hour or so together. I'd hoped that Faith Hubley would join us for the interview, but she did not.

On top of all that, I felt a certain apprehension about the interview because so much of what Hubley had said to other interviewers, and in his writings, was hostile to the kind of Hollywood animation that I loved and was writing about. (A Hubley-written article in the spring 1975 issue of The American Scholar was titled "Beyond Pigs and Bunnies: The New Animator's Art.") Happily, my apprehension was not justified. My wife, Phyllis, was with me, and we both came away liking Hubley a great deal. He seemed completely natural and unaffected—a man used to having his way in artistic matters, certainly, but direct and unpretentious.

What follows is my transcript of the complete interview as originally typewritten, with very small tweaks in a few places. My questions are a mixture, covering the earlier years that were of the most interest to me, as well as the Hubleys' more recent independent work. I hoped and expected that I'd have a second interview with Hubley, and I set aside some of the more sensitive subjects for that interview, in particular the 1941 Disney studio strike and Hubley's departure from UPA in 1952.

In November 1976 I'd just returned from California, where Milt Gray and I interviewed more than two dozen people for Hollywood Cartoons over the course of a couple of weeks. I'd been burned in my interview with Bill Hanna when I brought up, much too early, what I should have realized might be a touchy question, about the circumstances of his move from Harman-Ising to MGM in 1937. Hanna had been relaxed and voluble, but once I asked the fatal question, the atmosphere cooled markedly and his answers became much more guarded. I didn't want to make the same mistake with Hubley.

As it happened, I was able to learn in detail from other sources what happened at UPA in 1952—information that I incorporated into Hollywood Cartoons—but I never had the chance to ask Hubley himself about that crucial episode. He died the evening of February 21, 1977, during heart surgery at the Yale University hospital. He was only 62.

Part of the interview deals with Hubley's unhappy experience directing Watership Down for Martin Rosen. I learned more about Hubley's involvement later, and I discussed his role in my joint review of Watership Down and Ralph Bakshi's Lord of the Rings for Funnyworld, in 1979. I've posted that review in the Funnyworld Revisited section of this site; you can read it by clicking here. Michael Sporn has posted scans of my 1977 Millimeter article about the Hubleys on his invaluable blog, and you can find those scans by clicking here.

The interview follows:

Barrier:Were you involved with the Bambi unit when it was on Seward Street?

Hubley: I have a memory of being over there, but I can't tell tell you whether I was actually located there or whether I just went over to a conference. I don't remember actually going over there until later; it was the same place [on Seward Street in Hollywood] that Screen Gems set up.

Barrier: I've gotten very interested in Screen Gems lately, because, I think I've mentioned to you, I've seen quite a few of the old Screen Gems cartoons—

Hubley: You mean that [Frank] Tashlin period.

Barrier: Yes, and from later on, when Howard Swift and Bob Wickersham were directing.

Hubley: They were there when Tash was there, too. Swift;

and in fact, Wick was directing. I don't know why Tash left. I never got a clear picture whether he was kicked out or chose to leave. They brought Dave Fleischer in, who was one of the world's intellectual lightweights. The only thing you could say good about him was, he was so out of it, he was so completely detached, that he was never any problem. He let you do what you wanted to do.

Hubley: They were there when Tash was there, too. Swift;

and in fact, Wick was directing. I don't know why Tash left. I never got a clear picture whether he was kicked out or chose to leave. They brought Dave Fleischer in, who was one of the world's intellectual lightweights. The only thing you could say good about him was, he was so out of it, he was so completely detached, that he was never any problem. He let you do what you wanted to do.

Barrier: Howard Swift told me that the only real problem he had with Dave was that Dave fancied himself a great editor, and he would go through the completed films, just cutting out beginnings and ends of scenes, more or less at random, and destroying any continuity from scene to scene.

Hubley: I never had that trouble with him, that I can remember.

Barrier: How long were you at Screen Gems?

Hubley: It was really only about a year. Then the Uncle Sam army started grabbing everybody, and I jumped over to the air force unit, which was a break for me also, because I got a chance to direct there. That was the first time I ever directed, there. I was co-directing under Fleischer, with Paul Sommer, but it wasn't the same thing.

Barrier: You didn't start co-directing at Screen Gems until Fleischer came in?

Hubley: Yes, with Tash I was strictly layout and story; I didn't get into the direction.

Barrier: Paul Sommer was an animator; he handled, I guess, the animation end of it...

Hubley: Yes, and then he got into direction; he was a very square director. He didn't understand what the rest of us crazy guys were doing. Dun Roman and Sammy Cobean—there was a lot of talent there. We had a lot of fresh thinking going on.

Barrier: I've seen one that you and Paul Sommer directed called Old Blackout Joe [1942].

Hubley: I have absolutely no memory of that. It's terrible, isn't it?

Barrier: It's not a good cartoon, but the layouts are really lovely—the camera angles, and the way you break down the space in the city setting. And a little black air raid warden is rushing around, trying to get rid of—

Hubley: A dumb idea; I think it was Tash's idea ... Did you ever hear about Milt Gross coming in there?

Barrier: No, I didn't know he worked there.

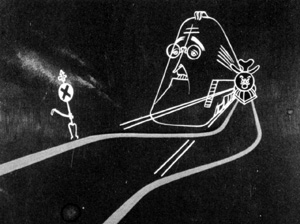

Hubley: Milt Gross came storming in one day, with Dave Fleischer and a writer by the name of Stephen Longstreet, who had written a lot of books. He had talked them into letting him do a cartoon; they wanted to do this for the war effort. They had this story, and we got assigned the job of actually making something out of it. We got to work with him—a fantastic guy, an enthusiastic nut. The story was He Can't Make It Stick [1943]—that was the title—and it was the story of an Austrian paperhanger who had this design for a wallpaper with swastikas all over it. He was going all over Europe, and pasting this wallpaper allover the place, and it kept falling all over him. It never really hung together—it was a small disaster—but we finished it.

Barrier: I think I mentioned another one I saw that had your name on it, called Wolf Chases Pigs [1942].

Hubley: Oh, I know—that was one of the first ones. It was in the works, I think, when we all hit that place. And Wick directed it, and he assigned me as a layout man. It was sort of the old order, wasn't it?

Barrier: It was sort of imitation Warner Bros., essentially.

Hubley: Yeah. Did you see the Tall and Small stuff [Professor Tall and Mr. Small, 1943]? And there was another one, a great one, that was made, which Columbia hated, and I think they just threw it right on the shelf. I doubt if they ever even released it. It was called From Rags to Rags, and it was a Horatio Alger myth thing, that this guy [John] McLeish designed. He did the whole board on it, and designed it, and we made that thing. It was really quite fun; he did the voice. It was very unusual; for that time, it was a real breakthrough. In fact, so much so that nobody could figure it. I've still got some of the drawings around, of this guy with a turtleneck sweater selling newspapers on the street at the age of 15, and then at the age of 20, the age of 25, all the way, until finally he's an old man and he's still selling papers. He goes through all kinds of different attempts to make riches, such as marrying a rich girl. At one point, he decided to become a songwriter; this was because Dave Fleischer said, "It's okay, you can do it if you make it a musical." So we put a song in it. They wrote this idiot song, and they had this one scene of this guy playing it on the piano and singing it, and then the camera was supposed to pan over the top of the piano, where there was a bust of Beethoven, and a tear was coming down. Fleischer didn't like that gag; he said, "That might offend Beethoven's ancestors."

Barrier: Did you work on a cartoon called Willoughby's Magic Hat [1943]?

Hubley: No, I think that was Sammy Cobean's. I forget who made it, but I believe Sam did the storyboard on the picture. [Art Babbitt] was with us for a brief period [at Screen Gems]; not very long, but I remember him out there. And Phil Duncan was there. Volus Jones was there.

Barrier: I think Art Babbitt said that you were the one who got him to come over to UPA.

Hubley: That's right.

[After talking about the UPA films held by the Library of Congress and the National Archives.]

Hubley: The Navy made this whole series they called "Flight Safety"; we did about seven or eight of them. I think I directed all of them; maybe Bobe did one or two of them. But I recall when I first came on there, I got into that right away. They had them restricted for a while, and then they declassified them entirely. And then I heard somewhere that there was a point when they maybe just totally junked the whole thing, and I said, "Oh, my God, they probably had dozens of prints." There may not be any left. I have a print of Flat Hatting; that's the only one I was able to keep—oh, I've got another one called After the Cut, which is on airplanes landing on a carrier deck. After you come to a certain point, you cut the motor off and you glide in. At that moment, there's always a lot of danger. And we did a bunch of little beat-up airplanes in a hospital ward, in traction and whatnot; Babbitt animated the whole thing. It's pretty funny. But that whole series was an entertainment approach to training films; it was quite unique.

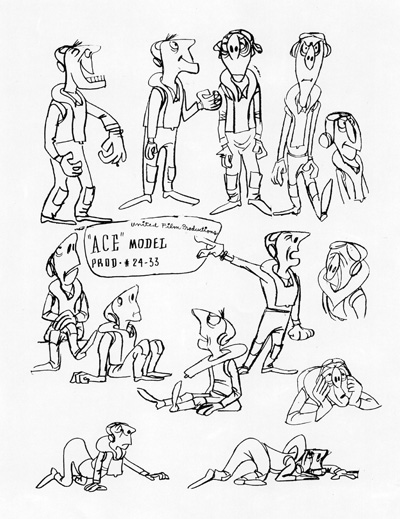

| Hubley's model sheet for a Flight Safety cartoon, Landing Accidents. Courtesy of Willis Pyle. |

Barrier: Like a continuation of the idea behind the Snafus and the Trigger Joes.

Hubley: That's right. I had a whole set of Trigger Joes, too. I had them up at UPA after the war, and the FBI came around and said, "What are you doing with those?" and took them away. They weren't classified, either. I've got storyboards for that stuff.

Barrier: Everybody who has seen them is very high on them.

Hubley: They were a very effective education technique. Mel Blanc did the voice. The guys that were being trained, the gunners, were mostly from Oklahoma and Texas, and would be like high school—no higher than that level. They would immediately identify this Trigger Joe character; he was one of them, just a big oaf. Well-meaning, and interested in trying to learn. So the narrator became the officer, the authoritarian, and the narrator was always trying to explain to Trigger Joe, and Joe would talk back to the narrator, and God, they loved it.

Barrier: There was really a mixed group in that Air Force unit—Rudy Ising, Frank Thomas, Jules Engel, you ... how did that group mesh?

Hubley: Oh, it was great. We had marvelous volleyball games. It couldn't have been better. There were two units—Frank had a unit and Bernie Wolf had a unit. There was a complete division as far as any kind of work overlap, so the rivalries, or politics, or whatever might have gone on didn't exist, as far as I know. I don't know what went on in Bernie Wolf's unit, but in Frank's unit, everybody was very happy. We had Bill Scott in there, and Bill Hurtz, me and Frank...then there was an animation pool, so both units drew on the animators. Rudy Larriva was there.

Barrier: Was Gus Arriola there?

Hubley: Yes—Gus had sort of a privileged position. He was doing his strip [Gordo] all through that thing—he always managed to get a little spare time off. But he was also the master sergeant to the unit—his responsibilities had to do with sort of Army discipline. But it was an easygoing [inaudible]. We got a lot done, too; we made a lot of movies.

Barrier: How did Rudy Ising fit in the picture?

Hubley: The guy would hang out in his office, and go to the officer meetings, and absolutely left everybody alone. He worked only with Frank and Bernie ... and beyond that, he was just a good egg ... If you hit him for a raise or something, he'd sort of shuffle around—"I'll see what I can do." He was just terrific. A guy by the name of Ray Fahringer was under him—he used to be an animator at Walter Lantz, and he was a flier; he was a captain. But he really was a tasteless character, as far as filmmaking—or insensitive. But he was also in it for the kicks; he was a flier, and [would] run errands, and do things.

Barrier: It doesn't sound like a very military—

Hubley: No, it was almost like a civil service unit. We used to say, many times, that it would have made much more sense for us to be civil servants. We lived the civilian status pretty much; we got to go home every night.

Barrier: Did you wear uniforms at work?

Hubley: Yeah, we had to wear uniforms at work, although most of us were walking around in shirtsleeves. I've got a million gags; we spent half our time drawing them and passing them around.

Barrier: Bill Scott said at the ASIFA banquet in Hollywood that he was in charge of the drill.

Hubley: That's right, yes. He had a little more GI training than the rest of us. He used to walk us into walls and stuff.

Barrier: Before we go any further, for the sake of this article in Millimeter, I wanted to ask you about your most recent work—Watership Down, for example. I've heard some rumors, but nothing more than that, about what happened, and I've wondered what was involved there.

Hubley: Well, I guess essentially what was involved was a conflict—interpretation of the contract. I always assumed that I had total creative control, and we started running into conflicts over what to do and how to do it, schedules, money, all kinds of things. It just got impossible. So the producer, having had most of the cards, I guess, in terms of the contract, or in terms of what he thought was the contract, said, "Okay. I'll finish the picture." So I filed a suit for breach of contract; he's probably going to file a countersuit. And beyond that, I'm really not supposed to talk about it. I've probably talked too much about it already. It's one of those unfortunate things. Doing a feature, there's an awful lot of money involved, and the people who control the money have a lot of power no matter what the hell the contract says. You just have to have a working relationship that's symbiotic. You can write five thousand pages of legal document and it doesn't mean anything if the damned working relation [inaudible].

Barrier: I would think the temptation with a picture like that—not for you, but for other people—would have been to make it too cute, and to take a sort of Bambi-ish approach to it.

Hubley: Yeah; there's a tendency to go into that direction, and also—there's a lot of conflict [inaudible] how much violence you put in. This is the age of violent films.

.Barrier: My reaction when I heard about the film was that it was going to be incredibly difficult to make it work, to make the rabbits be rabbits and yet have personalities.

Hubley: That's right. Really, in logic, it should have been a Disney concept; they had a chance at it, but they didn't like it. Frank wanted it; I think Frank liked it very much, but the brass upstairs thought it was too allegorical. ... I really couldn't say whether they had a clean shot at it or whether it was still involved with Martin Rosen. They might have taken it clean, but he wasn't about to do that; he wanted to make a kind of a co-production deal.

Barrier: How much work had been done on it when you were called in?

Hubley: Oh, I started it.

Barrier: From scratch?

Hubley: Yeah. We got practically a full animation reel; it wasn't quite fully animated.

Barrier: You mean like a pose reel?

Hubley: No, rough [pencil animation]. We had a lot of the dialogue and some of the music. I worked a year on the thing.

Barrier: When did you start?

Hubley: I started in August of '75, and in August of '76 was the blow-up. Not that I lived there a year; I was back and forth a lot. They have a six-month visa setup over there; otherwise, you pay a double tax. So I really had to stagger my time over there.

Barrier: How much of the work did you do with the British crew and how much with Americans?

Hubley: There was a group of Americans that did a big chunk of the work. Bill Littlejohn, Phil Duncan.

[Some conversation followed about A Doonesbury Special, on which Hubley was then beginning to work. Hubley said that the project originated when Trudeau approached John and Faith about making the film. Trudeau was a student of Hubley's at Yale in 1968.]

Barrier: You've taught at Yale several times, haven't you?

Hubley: Yeah; we've still got a thing going this semester.

Barrier: You made Cockaboody in, I guess, '73....

Hubley: Yeah...what we did is, we got the project together and then we took it to the class, and we'd show it to them, and we'd work on the concept with the students. In other words, they would get the same assignment we had—a terrific exchange. We did the Erikson project that way, and the Voyage to the Next.

Barrier: Is the Doonesbury project basically what you're involved in at the moment?

Hubley: Well, we've got two or three others ... a big, long special, which we're not really prepared to talk about yet. We're right on the verge of work.

Barrier: I wanted to ask you again about your work at Yale. Now, what you see on the screen in, for example, Everybody Rides the Carousel—none of the actual animation or artwork originates in the class, or from the students, is that right?

Hubley: Right. Ideas to kick around, you know; but we always—like on the Erikson [Everybody Rides the Carousel], we had eight weeks up there and there's eight stages, so every week we brought in our roughs—stage one, stage two—and then we would assign and discuss the following one coming up, so that they would have certain specific assignments. And they would bring in little sketches—we didn't care what form. But they never actually got involved in the specific production. They experienced the conception. The name of the course—it still is, in the catalogue—is "Visualization of Abstract Concepts." We've been doing that now for about eight years ... and it's very stimulating. Each year, we get more applications. What it amounts to is, you take ideas, or concepts, that it's very difficult to think of doing with a photographic camera ... and have to come up with ways of visualizing them.

Like the international law thing we did. We had this commission from the World Order Institute to do a film on the whole international legal system [Voyage to the Next]. The assignment was, what kind of a visual idea can you come up with that would represent the condition of nation-states today—the lack of any kind of a world government, a bunch of independent nations that are all on their own. They interact, and interrelate, but there's no legal system that binds them at all. We came up with a lot of different notions—the students came up with like a bus full of all kinds of ridiculous people traveling down a road. That was one of several metaphors. The one we kind of all settled on was this idea of a bunch of floating boxes, not going anywhere in particular except down the stream of history, bumping and banging into each other. That's what the class is about. And they're terrific, because they're such bright minds.

Barrier: So the class is not really concerned directly with animation at all.

Hubley: No, it's really conceptual—how do you start conceiving a film—and some of them are even thinking about live-action films. We don't care what the medium is, it's conceiving in different ways.

Barrier: A number of films, like Voyage to the Next, are personal films—have a personal style—but yet you have support of some kind. I was wondering how firm a line there is between your commercial work and your purely personal work. Is there really a hard-and-fast line, or is it kind of fuzzy?

Hubley: Ever since 1956, when Faith and I started working together—we made a decision that we were both interested in filmmaking, she had been making films by herself, she had also been painting and drawing a lot, so she wanted to get into animation with me, or art film, or whatever. We made a decision that we would just do the kind of films that we wanted to make, and find ways of getting them financed. Instead of waiting for somebody to come in and say, "Let's make a great film on ball bearings," we'll go to them with what we want to make. Or, if they do come to us, they come to us with something that really interests us. The first one was that Guggenheim film [The Adventures of *]. The assignment was simply to try to do something in the field of abstract art, with the idea of abstracting images that the public might understand. Other than that—make a work of art out of it. So we went straight at what we thought was a kind of a popular way of dealing with abstract art, with a story, and then we got involved in it, and after a while, we just made it the way we liked to see it.

We were determined to make some kind of a visual breakthrough, using a technique that had never been done before ... that led to that resist idea [what Hubley described elsewhere as "the wax-resist technique; drawing with wax and splashing it with watercolor so you produce a resisted texture"], and it got very exciting, because it really loosened things up. [Emery] Hawkins did a lot of that animation; he worked loose anyway, and by the time we added that crazy watercolor stuff—we had a lot of fun on that. From then on, each film became a sort of personal film, with a point of view, a feeling that filmmaking is an art and the filmmaker is an artist, and he does what he wants to do, and if the public likes it, great, and if they don't, too bad, maybe they'll like it a hundred years from now, which is the way any artist would go to work, since the Middle Ages.

Barrier: Is a distinguishing mark of your personal films maybe that even if they are sponsored—somebody gives you some money to make a film—that you don't worry about adhering to a certain budget? In the Guggenheim case, did you worry about whether you had enough money from Guggenheim to pay for it, or just go ahead and make it, and if Guggenheim's money didn't quite cover all the cost of it...

Hubley: We put our own.

Barrier: You put your own money into it, in addition to the Guggenheim money?

Hubley: Yeah, in that case we did. We went over on that, and we put some dough in it. But, see, at that time we were doing a lot of commercials. It was very affluent times as far as animation commercials were concerned. So it was just a matter of putting a little extra dough into them to make them good. But basically, we were very conscious of budgets, and as time went on, we got more so. In other words, for a while we were a little crazy, kind of. But as time went on, and we got $25,000 to make a short, we kept it under that.

Barrier: Of course, some shorts you've made, like Moonbird, you didn't have any outside money to start with.

Hubley: That's right. Tender Game, Moonbird were strictly our own. And we always had a hassle with our business managers and accountants, but we'd just do it, that's all. They would always result in new work coming in; there was always a followup. Secondly, they were the kind of things you win the awards with, because they're the pure work.

Barrier: Could you say your work falls in three categories—your purely personal work; the sponsored work, which is personal but has to meet certain criteria set by the sponsor: and your purely commercial work, like a television commercial. Is it possible to break it down that way?

Hubley: Yeah, I guess that's one way of categorizing it. The third category we're pretty well out of now; we don't do commercials any more. Even the television stuff we do[has] special status, like Doonesbury. We're in partnership with Trudeau, in effect, but we have a lot of creative control.

Barrier: In other words, you're not going to make any Dr. Seuss specials.

Hubley: Well, in effect that's similar. We could say that Dr. Seuss is [inaudible] man, not too much different from Trudeau, except that we've got such a great relationship with him, and he's so amenable to ideas. We feel very much a part of this, where if Ted [Geisel] came in and wanted Cat in the Hat... I wouldn't say we would necessarily turn that down, but it would have to be a kind of collaborative [effort]. But what we're really doing is our own special projects, like the Erikson. It took a long time, but—

Barrier: I was going to ask you how you managed to get that on network television for two hours.

Hubley: Sheer doggedness. I gave up a couple of times, but Faith kept saying, "No, we're going to do it, we're going to sell it, we're going to find a way." I'm starting on a book on the aesthetics [of animation]. I'm going to try to do some analysis of just what the hell the nature of the medium is in relation to art and drama and all the other media, what are its unique characteristics.

Barrier: I want to ask you about how you got involved with UPA. I guess Dave Hilberman and Zack Schwartz were both at Screen Gems when you were there.

Hubley: Zack was there; I can't remember if Dave was or not. I'm not so sure Dave was, because I don't think Dave and Tash got along very well.

Barrier: No, Dave was there when Tash was there. In fact, when Tash went back to Schlesinger's, Dave went with him as his layout man. They didn't get along very well at Schlesinger's; they didn't last very long as a team.

Hubley: I don't have any recollection of Dave being around, but he might have been with one of the other units.

Barrier: I think Zack was with Wickersham and Dave was with Howard [Swift]. I think Wickersham had somebody he wanted as his layout man and tried to ease Zack out, or something like that. But, anyway, did your friendship with Zack at Screen Gems have any particular influence on your going into UPA later on?

Hubley: Oh, sure. We always had a lot in common—ideas,

the kind of things we envisioned doing, new ways of seeing

things. Zack was a real leader, especially in graphics. He

did some stuff at the early UPA stages [inaudible] pure designing. Zack

and Dave and Steve formed that outfit. I was in the army then,

out at the air corps making Trigger Joes. They came—how did

that happen? Oh, yeah. A guy from the [United] Auto Workers called me

up one day, and he said, "I'm the educational director of the

Auto Workers, and we want to do an election cartoon. I understand you're pretty good." So I met the guy, and we hit it

off great—just one of those instant friendships, same sense of

humor, same cynicism, everything. I found him fascinating, because he was a very experienced cat, being the educational

director of the Auto Workers, under R. J. Thomas. He said, "Okay,

I'll commission you to do a board on this thing, [inaudible] and

get it made." So me and Bill Hurtz did a storyboard, called Hell-bent for Election [1944]. They all liked it; this educational guy

sold it, got some [inaudible]. The next question was, who was

going to make it. I was in the army, I wasn't in much of a position to do anything studio-wise. Hurtz was in the army, too.

First we thought of Chuck Jones. Chuck was, I guess, at Warners

at the time. And then, I don't know how in the devil it happened, Dave and Zack I guess heard about it, or something. They said, "Look, we're forming this little outfit"—and Bosustow got the equipment together, apparently—"1et us take it on and we'll get Chuck to direct it," and so forth. So they took it over and made it; Chuck directed it.

Hubley: Oh, sure. We always had a lot in common—ideas,

the kind of things we envisioned doing, new ways of seeing

things. Zack was a real leader, especially in graphics. He

did some stuff at the early UPA stages [inaudible] pure designing. Zack

and Dave and Steve formed that outfit. I was in the army then,

out at the air corps making Trigger Joes. They came—how did

that happen? Oh, yeah. A guy from the [United] Auto Workers called me

up one day, and he said, "I'm the educational director of the

Auto Workers, and we want to do an election cartoon. I understand you're pretty good." So I met the guy, and we hit it

off great—just one of those instant friendships, same sense of

humor, same cynicism, everything. I found him fascinating, because he was a very experienced cat, being the educational

director of the Auto Workers, under R. J. Thomas. He said, "Okay,

I'll commission you to do a board on this thing, [inaudible] and

get it made." So me and Bill Hurtz did a storyboard, called Hell-bent for Election [1944]. They all liked it; this educational guy

sold it, got some [inaudible]. The next question was, who was

going to make it. I was in the army, I wasn't in much of a position to do anything studio-wise. Hurtz was in the army, too.

First we thought of Chuck Jones. Chuck was, I guess, at Warners

at the time. And then, I don't know how in the devil it happened, Dave and Zack I guess heard about it, or something. They said, "Look, we're forming this little outfit"—and Bosustow got the equipment together, apparently—"1et us take it on and we'll get Chuck to direct it," and so forth. So they took it over and made it; Chuck directed it.

Barrier: Was the story as it was made the board that you had done? They were essentially the same?

Hubley: Yes, oh, yes, practically.

Barrier: What made you think of Chuck? Was it because he had been active in the union?

Hubley: Yes, he was in the union, and also I knew he was a Roosevelt man.

Barrier: But you weren't involved in the work on the picture after the storyboard stage.

Hubley: No, I didn't do anything past the board. I've got the original board here. Also, I've got a print of it; it's interesting, as a piece of history, a personal and political cartoon. And they claimed they did very well with it; this guy in the Auto Workers was very excited about the results he got, because the union guys liked it. Not that Roosevelt had much trouble in that election. We went right into Brotherhood of Man [inaudible] board, based on this pamphlet. So we did that, and again it went over to UPA; I was still in the army, but by that time, I took more of an eye. I actually sort of directed it and laid it out.Bobe Cannon got involved by that time, and Bobe and I got all excited about Steinberg, and so we wanted to try to get into that; Bobe did a lot of the stuff in that. Phil Eastman worked on that.

Barrier: There were four writers credited on Brotherhood of Man—you and Phil Eastman and Ring Lardner, Jr., and I've forgotten who the fourth one was. Did you actually work on the storyboard with them, or did they make some contribution after you had done the board, or...

Hubley: It started with Ring, actually. Ring did a kind of a script, and in effect we sort of boiled down the words, and then we took those and visualized them and came up with some little ideas about world community. I think it was mostly me and Phil; I don't remember anybody else unless—was Hurtz on there?

Barrier: I can't recall. I'm trying to think what the guy's name was ... he was a live-action script writer.

Hubley: Oh, Maurice Rapf...he's still around, I think, writing scripts out in Hollywood. His father was [Harry] Rapf, a producer at Metro for years.

Barrier: So the Auto Workers went to Ring Lardner and Maurice Rapf to get them to do a sort of script, and then you and Phil Eastman took it over?

Hubley: Yes, and visualized it. Then I took it into direction and Bobe animated it. Bobe sort of directed, too, because I was still half air force. I was doing a Trigger Joe on the B-29, with an automatic firing system. By that time it got pretty complicated—automated gunnery.

Barrier: So you were working nights and weekends...

Hubley: Yeah, right.

Barrier: When did you leave the service and go to work for UPA full-time?

Hubley: November of '46 [actually, Hubley was discharged as a staff sergeant in November 1945].

Barrier: Brotherhood of Man, I guess, had been completed by that time.

Hubley: I think it was finished, yes. The first thing I did was I got onto those navy training films, and a couple of filmstrips, too. That's right, we did a couple of filmstrips for the Auto Workers that I drew; I remember drawing them. Then Millard Kaufman came in; he was just coming out of the Marines. He came in as a writer. When we got the Columbia contract, he started doing Magoos.

Barrier: Kaufman was there for a while, then he left, and then he came back briefly to work on the first Magoo, is that right?

Hubley: Yeah, I think so.

Barrier: At the time you went to UPA full-time, had Dave and Zack already left?

Hubley: They were there for about six months, or something. It wasn't long. I think Zack did the first Flight Safety one, Fear—no, he did that with the Capra unit. That was over at the Capra unit; Zack was working there as a civilian. Then came UPA, and I think he did one or two of the Flight Safety things, but neither Zack nor Dave were very excited about that navy stuff. It sort of bored them, so they were happy to see me take them over. I brought Phil Eastman in, and the two of us used to go back to Washington and meet the admirals and all that stuff. We did about six of those. Zack and Dave got into this hassle with Steve. They really were the company; I was just an employee. When they broke up, they got into this hassle and tried to buy each other out. They both came to me and said, "Which side do you want to be on?" Which is a little different...

Barrier: Steve said that originally the idea was that Zack and Dave would buy him out, and they couldn't raise the money within a specified period, and as a result he had the opportunity to buy them out, and he was successful in raising the money, and they left.

Hubley: I'm not sure, but I think I was the key to it, because they came to me and wanted to know if I would continue there and stay on.

Barrier: Zack and Dave did?

Hubley: Yeah. Then Steve came to me, and in effect said the same thing, except that his offer was more concrete. He said,"I'll give you a big piece of the stock." The other guys were just talking about staying on as an employee. Also, they had a kind of an attitude like I lowed it to them somehow, which pissed me off.

Barrier: A little arrogant?

Hubley: Yeah. Like, "Come on, now, we're old friends, you're going to be on our side." I just weighed the two and I decided I would have an easier time being the creative head of the studio with Steve as the business head than I would with Zack and Dave, who were both creative guys. I'd be No.3 and I'd never have any clout there. And I really wasn't totally tuned in to them artistically: we had differences of feeling about stuff. I went with Steve, and I think that made the difference in terms of their ability to raise the money to buy him out. But I'm not sure of that, because I didn't pay much attention to it. So, anyway, Steve won and he bought them out. He went ahead and made those navy things, and then he got the Columbia deal.

[As I've written on pages 517-18 of Hollywood Cartoons, Schwartz and Hilberman offered a different version of the split, one that did not involve a competition for Hubley's allegiance.]

Barrier: And from the time that Steve took charge, you were the creative head of the studio.

Hubley: Yeah, I was vice president, I had, I guess, 25 per cent stock. I considered myself the head of the whole creative end, and he would go out and get the jobs, and so on, and get them made.

Barrier: What impact did Steve have on the creative side? Any at all, really? Giving final approval to projects, or passing on ideas...

Hubley: In the beginning, he didn't have any—nobody paid much attention to him, because he was not considered a creative guy. Certainly not an avant-garde creative guy; he had the technique and all, but...and he was happy with his role, and very supportive in anything we did. He was perfectly happy to have it happen. Then, later on, in the big building, and Columbia, and won an Oscar, and so on, he began to act more like a creative producer. He would want to okay ideas, and things like that. But I would say he was never much of a problem; we just went through the motions for him. He was always very supportive of anything we wanted to do.

Barrier: What about budget considerations?

Hubley: He was always fighting us on money. We were fighting— at least I was; I don't know, Cannon may have been more pecuniary than I am. I was always going over budgets, and Steve was screaming. I was [inaudible] theory that it would be better to do a really great, first-class picture at this point, [inaudible] get the money back later.

Barrier: I believe he said on Rooty Toot Toot, for example , that you and he had some conflicts over budgets, and he finally said, no, this is all we can do—

Hubley: Yeah.

Barrier: —stop the picture.

Hubley: I can't remember that; it may have happened, but I don't remember that. It probably did, because we were going pretty high on that. But it still came out very close to what I liked.

Barrier: The one thing he cited that he thought was not successful was the sequence where Johnny comes into Frankie's garden and it's sort of white-on-white, and there's not much color accent at all, just essentially the white outline characters. He was arguing that this should have been redone to get away from that.

Hubley: I don't remember that, but I never listened to him on any [inaudible]; I mean, the whole idea of that was the lily-white concept of pure little Frankie. Anyway, I've really got to start thinking about leaving now. You're writing a piece for Millimeter now? Be sure to write it in terms of the partnership of me and Faith, because all of the films, right from the beginning of our stuff, from Guggenheim on up, have always been a very close collaboration, creatively and on every other level.

[Posted March 10, 2011]