INTERVIEWS

David Hand

An Interview by Michael Barrier

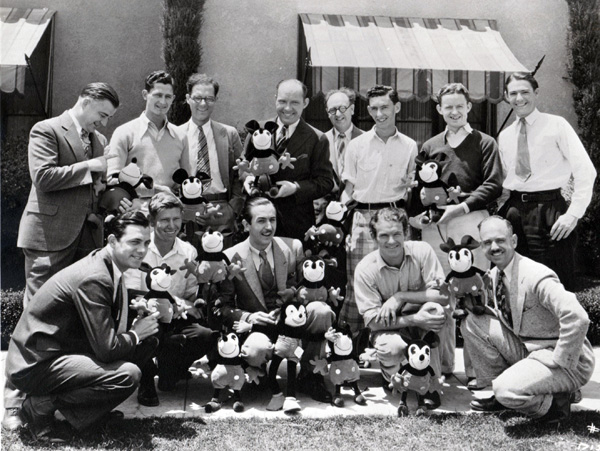

| David Hand is kneeling at the far left in this Disney studio group photo made soon after he joined the staff in 1930. Standing, from left: animators Jack King, Les Clark, and Tom Palmer; director Burt Gillett; composer Bert Lewis; animators Dick Lundy and Norman Ferguson; Floyd Gottfredson, artist for the Mickey Mouse comic strip. Kneeling: Hand, who was then an animator; director Wilfred Jackson; Walt Disney; animators John Cannon and Ben Sharpsteen. |

[To hear a brief (412 KB) audio clip from the Hand interview (MP3 player required), click here.]

David Hand was an immensely important figure at the Disney studio, but he was rarely interviewed, and his autobiography says very little about his Disney career. My interview with him—supplemented later by correspondence and phone interviews—was almost certainly the only time he talked extensively about his Disney experience for publication. In 1988, I permitted Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston to read this transcript when they were writing their book on Bambi, and Thomas said that one part of the transcript, included here, was "the best description of Walt and the studio and the working arrangements I have ever read."

David Dodd Hand was born in New Jersey on January 23, 1900. Exactly thirty years later, he went to work for Walt Disney as an animator. Hand had at first pointed himself toward newspaper cartooning. He moved to Chicago to attend commercial-art classes; then, when he ran out of money, he found a job at Wallace Carlson's "Andy Gump" studio. From there he worked his way through the animated-cartoon studios of New York City before taking a job at Disney's. He seems not to have distinguished himself in any of those earlier jobs, or even to have ingratiated himself with many of his fellow animators. At the Bray studio in New York, his colleague James Culhane later wrote, Hand "had an air of superiority that was foreign to the free and easy atmosphere."

Hand was not held in much higher esteem when he was animating at Disney's. His animation was "too mechanical," said Dick Lundy, another Disney animator in the early thirties. "He used to get a lot of birds, and he would chart the stuff out"—that is, Hand planned the flight of the birds in advance, as opposed to letting his animation flow. Such military precision, evident in Hand's animation of a flock of birds in Flowers and Trees (1932), has nothing to do with the way birds really fly.

Like his fellow director Burt Gillett—and Walt Disney himself—Hand probably lacked the ability to do anything particularly well, except be a boss. Unlike Gillett, though, Hand knew how to be a boss without challenging Disney's own authority.

Disney made Hand a director in 1933—his first cartoon was Building a Building, with Mickey and Minnie Mouse—and over the next few years Hand directed some of the best Disney shorts, among them The Flying Mouse (1934), Who Killed Cock Robin? (1935), and Three Orphan Kittens (1935). When Disney decided not to direct Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs himself, Hand got the assignment. Over the next few years, he served repeatedly as Disney's surrogate, overseeing the shorts and then Bambi, and exercising broad authority over many of the studio's operations. In all of these jobs, his manner was that of a very forceful, broad-stroke business executive.

Hand didn't linger over the details of each cartoon, as Wilfred Jackson did. Instead, he put a lot of work into assembling strong casts of animators for the shorts he directed. It wasn't special treatment from Walt Disney that permitted him to assemble his strong crews and schedule their work smoothly; he simply sought those advantages more aggressively than Jackson or Sharpsteen did. (His greater efficiency probably won him assignments that would otherwise have gone to one of his colleagues: the story outlines for both The Flying Mouse and Who Killed Cock Robin? show Jackson as the anticipated director.)

Hand became the quintessential Disney director—and the logical choice as Disney's second in command—because he devoted so much effort to giving his animators the characters and sequences that they could make the most of. Increasingly, in the thirties, a Disney director's job was to support and cushion his animators, with responsibilities of other kinds shifted elsewhere. When Hand spoke to one of Don Graham's classes early in 1936, he said the voices for the cartoons soon might be chosen, and the dialogue recorded, by the story department, before the story got to the director. "It would be fine for the director," he said, "because then he could give the animator more time." Walt Disney distributed the transcript of Hand's talk, with a laudatory cover memo, to the other directors, the story men, and the principal animators.

Jack Cutting, who worked briefly as Hand's assistant director in the mid-thirties, recalled that "the more he found you could do, he would unload it on you." But Hand was by no means a lazy man who dumped too much work on assistants. Instead, Cutting said, he was "ambitious, doing a lot of work ... a hard driver"—delegating work to capable subordinates as a successful businessman might, that is, rather than sloughing it off.

"Walt was always in charge," said Eric Larson, who animated the owl for Bambi, "but Dave was a good wrangler." Wilfred Jackson "was the better director by quite a bit," the animator Frank Thomas said, "but Dave was the better organizer and driver." Chuck Couch, a writer on the Disney shorts when Hand supervised them, remembered Hand as "a very practical guy. ... If Dave liked something he'd tell you it was goddamn good. If it was bad he'd say it stinks. You always knew where you stood."

Hand's business-like attitudes came through in what Dick Lundy remembered as his advice when Lundy became a director in the late thirties: "Now, there's one thing you've got to do, Dick, you've got to make decisions and you've got to make them fast. If you're right 51 percent of the time, you're right."

In 1938, just after Snow White's release, Hand drew up an elaborate organization manual. That manual was a response to the nightmarish logistical problems that arose during work on Snow White, when the studio grew rapidly and the old informal structures proved inadequate. It seems doubtful, though, that Hand's highly bureaucratic manual could ever have been the solution to such problems, even if Walt Disney had cooperated—as he clearly did not. Disney, like many another entrepreneur, bridled at the thought of submitting himself to the authority of an organization chart.

Hand's position was fundamentally untenable—he was second in command in an organization whose leader, younger than Hand himself, had no intention of ever stepping aside or sharing real power—and he finally left the studio in 1944. He spent several years in England, trying unsuccessfully to establish a Disney-level cartoon studio for the J. Arthur Rank organization, before returning to the United States and an uneventful career with the Alexander Film Company, which made commercials and industrial films in Colorado. In 1967 he moved to the small town of Cambria, on the California coast. He died there in 1986.

I interviewed Hand in Cambria on November 21, 1973; we met one evening at the town's Veterans Hall, when my wife and I were driving down the coast from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Hand was no longer the handsome young go-getter whose tailored sports coats led some Disney writers to nickname him "Shoulders," but he still had the direct, almost brusque manner of a businessman with important things to do. Predictably, he had little to say about the people who had worked under him; his attention was always on Walt Disney, and he was concerned most with reading his boss's moods and wishes.

DAVID HAND: I was there, and I saw it, and I saw one man—who was a genius, no question about it—get the credit. It didn't bother me at the time, nor did it bother anyone else, because we were so busy, so immersed in developing this great art, and having someone—Walt—allow us to take the time to develop. Up to that time—and I had worked ten or eleven years before then—you couldn't have time to develop anything. You were given so much money, and you got the picture out for that amount, or you got out. It was a question of who got out first. With Walt, all the artists—and I include the story man, the contributor of ideas, the music composers, too—we were all so immersed in the development of this great art that we didn't want any publicity. In fact, we wouldn't talk, we didn't have time to talk. But further than that, I know, as it went on, that there was a prohibition from the front office: don't mention anybody but that one person, Walt. And if I'd set back and had time to meditate, I just hadn't liked it, because there was a tremendous creative contribution from these very fine artists. Without them, Walt didn't have a tool to work with.

But I must say he kept his tools sharp, and more credit to him. I wouldn't have been anything, and all these key men that you know about wouldn't have been anything in an animation studio without Walt. Walt fought the front office, because they wanted him to make the cartoon for a price. I've heard him. I was with him enough to know that he practically threw Roy out of his office two or three times, because Roy wanted him to make the pictures for a price in keeping with the market returns. But the costs of pictures increased each year. Roy would come in to the production department and say, "Walt, we can't spend so much, we're not going to be able to get the money back." And Walt, in his sharp, peculiar way, would say (Walt was younger than Roy, but he was the boss), he'd say, "Roy, we'll make the pictures, you get the money. Now goodbye, I'm busy." Then Roy would come to us, two or three of us together, and say, "Fellows, what are we going to do? You've got to work on Walt to spend less money on each picture!" Well, you couldn't work on Walt. That's the last thing you could do, work on Walt. Roy says, "I can't do anything with him. What are we going to do about it? I can't get the money." We didn't hear him.

Getting back to the artists—it was basically the opportunity that Walt gave all of us to do what we'd like, in line with what he thought was right. Walt couldn't really draw. I've seen him try, it was pathetic. Well, he didn't have to draw, did he? Better he didn't, because he would ask us animators, at the time I'm speaking of, to do things that were impossible to do. But he didn't know it. Good thing he wasn't an animator. As a director, when I had been an animator, I had to be considerate of the animator, and not ask him to do things that were impossible. That was my weakness, Walt's strength.

I started [at the Disney studio], I believe, two days after Ub Iwerks left. I started on my birthday, and how could I miss it. Ub had quit the Friday before, according to my understanding, which I wouldn't argue about. So I was that close behind Ub; I knew Ub later, but not at the studio. Walt talked about Ub to me. He said he was terrible when it came to staying at the drawing board. "His car was parked outside in the driveway"—very small place—he said. "Ub was out there all day working on his car, fixing it up, putting new things on it. I said, 'Ub, you can get a mechanic to do that job for ten dollars, come back in here and animate.'" They didn't get along, as you know, and Ub, of course, eventually went back to Disney as a technician [in 1940]. That was his forte, although he was a wonderful artist.

The other peculiar thing is, Walt said to us—there were probably eight or ten of us at the time, and Ub had just left—he said, "You fellows can have Ub's share of the business." I thought that was very nice. Of course, it was only a little studio, and no one had visualized the eventual size of it, so a few dollars more a week, or a year, what did it matter? But that's the last time Walt ever mentioned it. I often wondered, as time went on, what happened to it. I suspect his brother got after him and said, "You crazy idiot!"

You didn't take him up on the offer right away?

Oh, he felt badly that Ub left. You know the background of the two of them. From where I sit, Ub was the man who put Disney in the animation field professionally, because he was a professional animator, he could draw the characters, and Walt couldn't do any of that as well as Ub, so I think Ub had a lot to do with it.

Anyway, when I went there, we had had a little bull's-eye Movieola; you might have seen them. Not the Movieolas that project onto a little screen; it was just a magnification bull's-eye. And Walt would cock his eye—we would make our animation and have it photographed in pencil [the pencil drawings would be photographed for test purposes before they were traced in ink onto celluloid] and put into a loop—and Walt would get his frown, one eye poked into that bull's-eye, and he was looking at it with his foot on the pedal, and he'd start shaking his head, and he'd start really tearing an animator apart, if he didn't get what he thought the animator should get. I can remember an instance of some animation I did when I was first there. We were not using assistants to any extent in those days; the animator usually did every drawing, and he did it cleaned up. We didn't always have an assistant to put the in-between drawings in, which is the accepted system today. We made extremes, and in-betweened them ourselves much of the time.

Dave Smith [the Disney studio's archivist] has written that one reason Ub and Walt quarreled was that Walt wanted Ub to use an in-betweener.

I don't know about that, but it sounds like Ub. It seems to me it was a transitional period—sometimes we used in-betweeners, and at other times, when there was a difficult bit to do, we did our own in-betweening.

Anyway, the animator had to get his drawings completed, and they were not rough drawings, at that time they were cleaned-up drawings, every one of them. Then he had them photographed. The test film was delivered to him for viewing. Well, that's a lot of time wrapped up in those drawings. I'm only going to make a point by saying that I well remember at this time that I had a particular Mickey Mouse taxicab scene to do [for Traffic Troubles, 1931], and I did my very best with it—as I of course would—and got it on the Movieola with Walt, and he squinted and squirmed and grunted, and said, no, it didn't have enough exaggerated action to it. I said OK, and back I went to my desk. Five times I brought that corrected scene to him, and each time I made it more exaggerated, and each time he turned it down. I thought, "What does this crazy man want?" I'd been in the business eleven years then, and Walt had much less time in the business—I never thought of that, though, I never thought that he didn't know as much as I, I never thought that, I just thought that he ought to know that this animation of mine is acceptable, that was all. So, the fifth time I went back to my desk, and again, making all the in-betweens, and the drawings cleaned up nicely, and had it tested—I went back this time, happy that at last Walt would approve it. He looked at it, shook his head and walked away. I was broken up! It wasn't right that I should have to do it that often.

Finally, I thought, "I'm going to show Walt he can't be that smart with me"—I'm a year older than him, and even though that didn't matter, it was just that he wasn't an older man—I said to myself, "I'm going to show that fellow a trick or two." So went back to my desk to redo this scene a sixth time, and I said, "I'm going to make this thing so extreme, so outlandish, so crazy, that he'll say, "Well, Dave, I didn't mean to exaggerate it that much." So I did, I was really dirty—the only time I remember being dirty with Walt—and I made that thing so outlandish, and so extreme, I was ashamed of what I had done. But I brought the new test in very self-righteously and put it on for Walt, and said, "All right, Walt, I did this thing over again, I hope it's OK," while slyly watching for him to explode—fly off the handle. He put his foot on the pedal, and he started the loop around and around and around, looking at it and looking at it. Then he stopped the loop and looked up at me with a big smile and said, "There! You've got it! Why didn't you do it that way in the first place?"

That lesson stuck with me as I progressed through the studio, into supervising animator and then director. A supervising animator had three or four juniors, and he would take a small section of the picture, or a third of the picture, from the director and farm it out to his juniors, and he would work with them to show them how to get what he was supposed to be able to get. That was a part of the development of the animator in the studio in the early days, and continued, juniors working under seniors, and seniors being responsible for juniors. The lazier the senior was, the more the junior got to do, because the senior would sit and read books and make the junior do the job properly, and that's how the junior learned so well.

So that lesson about exaggeration stayed with me through the supervising animation to the direction, and the supervising director that I eventually became. I never forgot that, and I think it might have shown up a little bit in my working with Walt—what he wanted, I suppose I could convey to an animator.

Where had you worked before you came to Disney's?

I worked with J. R. Bray. Milt Gross was making a series, for Bray, "Nize Baby." Later I worked with Walt Lantz. When sound came in, it was obvious to anyone in the business that this was something helpful to the cartoon medium—but how to use it? How to get the sound effects and voices to sync with the animation? I believe that all the studios at this time began trying to unlock the secret. I know that I was trying desperately to figure it out, and couldn't. And no one else seemed able to do it. At this time all the big studios were located in New York—that was the place where the action was. Disney was in Los Angeles, but he didn't count, really. Well, all of a sudden a cartoon was showing on Broadway—with sound, and perfectly [synchronized]. It set the animation world on fire. Steamboat Willie. Not only did it wake up the animation business, it became the rave of the movie houses. People talked about it, and sent their friends to see it. And Walt Disney was on his way!

I think I know the man who conceived it—Wilfred Jackson. I believe Willie knew the mechanics of music, as I did, too, but I didn't have his mechanical know-how. He knew—as anybody should have known—that twenty-four frames make a second, and you make twenty-four drawings, and jump them up and down in a second and it's in beat, in rhythm, and so on. That, of course gave Walt the jump on everybody. Walt's studio was no better—not as good, really—in animation as other studios. But Walt got the jump on all the other studios because he had synchronization. That was only the beginning. Walt had genius, too, but without first getting that jump on the other studios, nobody would listen to a genius.

When he synchronized the cartoon with the sound—music and so forth—it was like a whole new world opening up. [For me,] who had been in the business so long, to see these characters synchronized with sound, it was fantastic! I rather thought that that's something I ought to be able to do, but I couldn't, so I had to go out to Walt Disney. It was so simple when I learned how; it wasn't long before the other studios unlocked the secret, too. The way I see it, it gave Walt the edge on the other studios, then he had the good sense to make an animator do a thing right. He also had two more things: he had intuitive judgment, and he never forgot a gag he ever heard. I'm not kidding you. He never admitted a gag wasn't original with him, but you could many times trace the source of them. I don't know that he even knew it himself. I've sat in story meetings with Walt, and heard someone—A, B, or C—bring up a spontaneous gag, to go in a certain place. Walt's sitting there frowning. Looking usually someplace else, and before the meeting is over, he gets the idea out of the air—excitedly explains it—and it goes in the picture. He never even heard it mentioned earlier, except that he did hear it. What did he have, a catalog of thought that stuck it all away and then flipped it out? I don't know what it was, but I know he thought it came spontaneously from him. And it was with all his ideas. I call it genius; of course I call it genius, I'm not running the man down. He also knew how to get it on the screen.

Another interesting thing—I used to, as a director, fight with the story department—and Walt was one of them—because I didn't think an idea was funny; and a director had the final responsibility for the results of a picture. Once he took it into his room, it was his baby; no excuses. So I would fight with them. Walt was in there, too. They would fight back, and I would argue, and finally we would revise the idea so that I would be happy with it. Then I had to go through the same thing with the animator. He didn't have to take a scene that he didn't think was right, so he and I would sit in the director's room, and we would argue and fight—not to get him to take that scene if he didn't like it, but to try to get to work around until it was his scene, and then he could produce it on the screen. So it was with the director; when it became his picture, he could produce it, provided he was a good enough director. There would be ideas that I didn't like, and I would say I didn't like them. And the story men would work on them, and change them around until I was half-happy with them. Once there was one idea I just thought was rather terrible, and I said so, and Walt fought me, and he got mad at me; and he could be rather unreasonable, at times. Of course, he was the boss, but he usually was very understanding. But not this time. So I took the idea—I didn't want to—and went into the director's room with it. Some time later, Walt came in and I said, "Walt, I still don't like it." He said, "Oh, it's a good one, Dave, you do it. Do it just the way we told it to you." So I did; believe me, I did. I worked hard to sell it to the animator, and he didn't help. They'd just sit there and [say] "Yeah, yeah." Sometimes they wouldn't know whether it was good or bad. The scene came out on the screen—we always had our previews, sneak previews—and the darned gag fell flat as a pancake. The next day—there was always a postmortem—I said, "Walt, I didn't ever think that gag was any good." He said, "Jeez, Dave, you just didn't do it right." So I mumbled to myself and thought, "You can't win with Walt."

[The episode in question involved a scene in The Flying Mouse (1934). Hand described what happened in a letter to me in May 1975: "The mouse was being blown backward through the air, out of control. He was a sympathetic character in a sad plight. The 'laugh' gag was that his rear end would make a 'bull's eye' into a large thorn sticking out of a rosebush stem. Now, for me, the idea itself was not funny—especially happening to a pathetic little flying mouse. But I had been previously overruled in story, so when the picture got to me, I decided to play the impaling idea down as much as possible. However, Walt caught up with me when I was getting it ready for the animator. We had more argument, and I lost. Walt insisted that I make the thorn long, dark, and sharp—and that the mouse's rear end get buried clear up to the hilt. And further to this, that I have the music build up to a 'screech' accent. That poor mouse! The audience did not laugh at it, but it was one of the many instances where I found Walt to be surprisingly sadistic. He seemed to enjoy 'hurt' gags more than a lot of people."]

The development of the animators really took place with Walt's encouragement—insistence, actually. The good animator, as soon as he became any kind of a top quality animator, got burdened with kids who didn't know much about animation. It might be Fred Moore I'm talking about, but at the time Freddy Moore came in, he didn't know anything, and he went in as a junior, and the senior animator was burdened with him. He'd give him run-throughs, and jumps, and bits of this and bits of that. Of course, the sharp boys soon learned how to animate properly, and they had that feeling of "Disney." We were all "Disney," we never went against Walt Disney, we had married him, we wanted to do what he wanted—not necessarily because he was a boss so much as he was a leader, and the stuff was going out in the theaters, and people were liking it. So, throughout the years, besides all the details of animation development that we had in the studio—special classes and such—the basic system was the key animator taking on juniors, till they became, themselves, toward key. We had, to my way of reasoning as a director, three grades of animators: the key animator, the junior animator, and the assistant to the junior. Key animators were cast as you cast a character actor. Some of them could do one kind of thing, and some another; one kind of thing not so well as the other. They became specialists in some kinds of animation. So we cast them, and the juniors under them were learning that kind of animation, or else they would be moved to somebody else if they showed greater talent in another kind of animation. So a key animator ended up with rather a fair group of assistants in one manner or another, all developing, and all under the pressure of quality, and Disney in back of it.

In many cartoon directors' films, you can see in the animators' work the director's personality, and what he wanted.

That would be true—I think you mentioned someone like Chuck Jones [at Warner Bros.], and his strong poses—but in the Disney studio, that was Walt.

But, even so, you had to get the animators to do what Walt wanted.

Yes, and they wanted to do what Walt wanted, too, there was no problem there. They worked hard to do it.

You've mentioned that you never saw any politics, that the competition among directors for animators was friendly.

Yes, that is right, and I would have seen politics being played because I was close in animation, close in direction and over-all studio supervision. I never had anyone come to me playing what we termed politics. I think a large part of the lack of it was that Walt didn't encourage political maneuvering, and he did not like apple polishing. I'm not a politician; but some people are naturally bent that way, and I think that Walt would sense it, squint and frown, and turn and walk away. That's why we weren't bothered with it in the studio.

The animator himself became like one you would cast for normal [live action] pictures. He became a certain type of person who could do certain kinds of animation better—not that he couldn't animate almost anything, but he did certain things better than anyone else in the studio could. He was naturally cast on specific types of characters and business. He would take with him his juniors and then give them the kinds of things that they seemed to like best.

Were there ever cases of animators who were best at a certain kind of animation, but who really wanted to do some other kind? I've heard that Milt Kahl, for example, would really prefer to do wilder, more cartoony animation, instead of the realistic animation that he does.

I'm smiling because certain animators were problems. They wanted to do one kind of thing, they couldn't do it well, but they insisted they could do it. I always thought of an animator as a highly creative artist who had a world of his own turning around inside him. An animator, particularly, couldn't see anywhere beyond himself. There were some animators who did insist that they could do other work better, and did get a chance at it, and did either do it or fail at it. We would probably give it to them to quiet them, as it were. Any particular instance that you might mention would be rather general in the studio, with a lot of animators, who are very temperamental. Oh, man, working with a studio full of artists, you've got yourself a problem. They all had temperaments of one kind or another, or they wouldn't be artists, and the better ones had more temperament—not all of them, but some of them. So, that would be true, but wouldn't it be silly for a studio, and Walt in particular, to say to Joe, or Jack, or whomever, "No, you just do what you're told and stay where you are"? A top man? A top man you work with, you don't want to misdirect him in any manner.

Speaking of the different animators' styles, the Disney cartoons seem to have succeeded better than those of other studios in keeping a consistency of style throughout the cartoon. If it's possible to get specific, how would the director do that, working with the animators?

Well, to begin, he would object to the casting of an animator on his picture, if the type of work was entirely out of his character. When a picture would be cast, in the shorts, the director would sit with Walt and the production manager, who knew where everybody was and when they were coming off their present assignment—a terribly complicated thing in a big studio. The director would have to know the animators, and he did know them, because he grew up with them. He would say, "I would like to have A, B, C, and D." "Well, you can't have B, because he still has a problem on the other picture, and they've got to do a lot of that stuff over." "Well, how about L or M? They do work like that." I'd give them a little less of the important stuff. So there was a sort of working back and forth until you got a crew that could pretty much handle the kind of picture that you were working on. And there were different types of pictures. Now, these [other cartoon] studios you speak of, I don't think they cared about that as much.

Most studios would have a crew of animators that would work with the same director, year in and year out. It sounds as if at Disney's, they would shift around.

Yes, we didn't have that at Disney. We'd cast the man for the kind of thing he could do on the kind of picture. We had a great many productions going through, as you know. The most interesting thing is the organizing of that vast amount of talent.

I recently re-read the Robert Feild book, The Art of Walt Disney [published in 1942; not to be confused with the 1973 book of the same title, by Christopher Finch], which deals in large part with the organization of the studio. From the book, it sounds as if the studio was very well organized, and yet also very loose, so people could be shifted around as they were needed.

I had a lot to do with that, in organizing the studio, because I was eventually in that particular capacity, where Walt was in the story department and I was taking care of the rest of the details of production. There was so much manpower, and each one of them was a temperament that you just couldn't push around like you push "nuts and bolts" people around. The problem was to get a group of people to the right place at the right time, in order that they would be able to handle the kind of work that was coming through. The kind of work—not any work, the kind of work that was coming through. So it took a vast organization of controls, and memos that went out continuously. That's hard enough in a big studio; but we had a boss-man who didn't care anything about army organization. He didn't care about the general being the top man, and that he should go through the brigadier in giving orders, and on down the line to the private. He thought he could, and he did, tell the corporal to have the captains and the majors see that the rest of the privates were over here doing something else. And if you were a corporal in that studio, you hopped when the general told you to.

I'm talking about Walt, of course. Walt didn't care anything about the details of organization. And he caused a great deal of trouble by ordering a certain man, or his group of men, to do something else right now. This whole organization was supposedly working properly, and we were so interrelated, all of us, that when this happened we would immediately tell the other guys what went on, so it didn't go on for long, probably half an hour, before the man that Walt had told to change something, some routine, saw to it that the information got right back up to me. Then, right away, my secretary had to start those memos going out, changing the order of things. We never tried to deny Walt the right to do it, but we had to get the memos out to all the other departments saying that signals had been changed, and we're going to do it this other way. Then the organizational charts we had, telling how the operation was to take place, had to be changed—it was a mess.

Of course, the kind of man Walt was, you couldn't expect him to care anything about organization, and he didn't. And he would do these things, and it didn't matter who he spoke with; but fortunately, we had a vast Dictaphone system, we could call anyone with a button, never mind going through operators. This was before we went over to Burbank, this was on Hyperion. The director had about thirty keys he could push, to get anybody he wanted, and the animators had certain keys they could push—not as big a set of them. So it wasn't long before everybody in the studio who was concerned knew the signals had been changed. And that's how the studio was run. Except in the meantime, we tried to have organization. I could go on for hours about organization, but that's about the way it was. It was a very strict organization; there was an organizational setup, and it took an awful lot of time and a lot of people to see that it worked.

Did this degree of organization become necessary when you began work on the features?

It developed during the first feature, and we couldn't have produced the feature without it. I'm speaking of Snow White, which I was cast on as supervising director. We had a deadline, and there was also a very definite financial problem at the studio at the time, and we almost went broke. We had two deadlines: one was to get a rough viewing product ready for the bankers, an example picture—some pencil animation, some stills, some music, whatever—to get some more money from the bankers. We then had spent $750,000 (all Disney money, I believe), which was a lot of money in those days, and we needed nearly another $750,000 to finish it. So that was the first deadline, to get the preliminary picture ready so we could get $750,000 more. They did give us $750,000 to finish Snow White, which made a total cost of about $1.5 million [officially, the negative cost was $1,488,422.74]. Then we had the deadline to completely finish it before Christmas, for Christmas preview. Everybody worked very hard to get that picture out, and did get it out, on deadline. But we couldn't have done it without organization, we just couldn't handle a thing like that without organization.

The studio's employment expanded tremendously, didn't it, when you began work on Snow White? I imagine that would have been chaotic without organization, adding all those people.

That's a story in itself, too, the adding of the people and the training and developing of them. There was no place to get them, but out on the open market. There was one fortunate thing, of course; that was done during the Depression, and good artists needed work. It made a difference. In other words, we were on the buying end, and the artist only had himself to sell, and he needed a job. I think that was one of the reasons we were able to get so many good people at that time. I know that we had 1,150 artists when we finished Snow White [actually, the studio's employment didn't reach that level until work was under way on later features like Pinocchio and Bambi]. The cost of pictures when I went there, I think was about thirty-five hundred dollars for Mickey Mouse. They went up to five thousand dollars, and that's when Roy started fussing with Walt, because he couldn't get five thousand dollars for a picture. You do know that the distributors were giving pictures away before Walt came along, don't you? Walt didn't like Roy complaining about costs, and he told Roy that he was going to make the pictures better. They got up to five thousand dollars and Roy felt terrible about that, because he had to go out and find five thousand dollars for every picture.

To cut a long story short, they got up to fifteen thousand dollars—$16,500 was one, I think, and that was too much. They couldn't, at that time, get that much money out of the market. That's how the feature idea was born. Walt said, "If we are making twenty pictures at 650 feet, and we are getting fifteen thousand dollars for one picture of 650 feet, why don't we make ten pictures for $150,000 and call it a feature?" So far as I know, it was Walt's idea to make the feature; I don't know how much he talked it over with other people. But the reasoning was—I know that, because of the discussions—well, look, they're only paying us so much, and we can't get any more out of the market, so [if] we stick ten of them together, then we can get maybe three or four hundred thousand dollars, whereas now they're only paying us $150,000, with no profit. Well, you know Snow White grossed I think it was ten million, which was exceptional at that time. Good reasoning. All the key animators went on the feature, of course, and the other guys stayed on the shorts, and the shorts suffered because of it, and never did quite recover.

I asked him to please let the animators invest in the company, and his answer was (and his thinking is interesting because now Disney is public), "No, Dave. Do you think I'm going to let an animator invest in this company and get a certain amount of investment, and get out of the studio and sit on his ass and let these other fellows staying behind do all the work while he doesn't contribute anything? I'll never allow that." And he wouldn't allow us to invest in his studio because of it. That, of course, upset me terribly, because the men were so dedicated, that he should not let them have some stock; but he wouldn't.

Snow White is roughly the length of ten or eleven shorts, and yet its cost was much, much more than ten times the cost of a short. What led to the great increase in costs?

Very simple. I'm being facetious when I say there were seven dwarfs, but it's true. More than that, Disney was insisting on a quality—and also he got mixed up in the multiplane camera, which was very expensive—he was insisting upon a quality where it was tremendously costly; and besides this, the animator didn't have a Donald Duck or a Mickey Mouse to animate, he had dimensional characters. A marvelous accomplishment, but every key animator of any note had to draw every character, not in graphic form, but in personality. When you can make the characters live the way the dwarfs lived, and get every animator to do it, and make that same character look alike, and act alike, you've done something—and that costs money.

They couldn't rely on formulas...

Well, when you say "formulas," I know you don't mean a circle for a head or a pear-shaped body, you mean a formulized character, the characteristics in the character. We used to sit as a group, in the large sound stage we had at that time, and people would get up and act out their impression of a particular character. The most interesting thing to me in the whole studio is something that's quite hidden, to make a character come alive, be born. Come to life dimensionally, not the way some of it's done. Every key animator had to know that character, and it was a great deal of effort to get every animator to know the character completely. I don't know if you appreciate the amount of creative effort that comes out of an animator to make the character live a certain way. Not Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and Pluto; they had few subtle shades. These Snow White characters that actually have these little idiosyncrasies, little twists and turns and little walks. Every animator had to know how to do it. And there were, still, seven dwarfs, and, of course, the live-action [that is, based on live-action film] Snow White and the Prince and such, and also the beautiful backgrounds, and the designs of the dwarfs' house, and the interiors, and so forth, which was mostly [Albert] Hurter's stuff. Tremendous cost to that.

How much animation had to be done over because of this? Was there a great deal of re-animating?

There always has been in the Disney studio. There always was while I was there, and if the animator learned from it—I did—it was well worth the effort. What you should have asked was, how much was thrown out of the picture?

There were two complete sequences thrown out, weren't there?

Very costly and finished at that, in animation.

Weren't they building a bed in one sequence, and eating soup in the other? What was the reason for not using those sequences?

They didn't seem necessary to the direct story line that we were following. You know, at the Disney studio—at least when I was there, I don't know about now—the story line was the most important part of a production. There was no hit or miss; it was all very hard work in the story department. Consequently, when these sequences were in, and the footage was so much, and it's too costly to finish, and it proved not to be really directly concerned with the picture—that was it.

We wore the sweatbox out—we called it a sweatbox, you undoubtedly know why [because of the nervousness the animators felt when Disney was looking at their animation], and later a small projection room probably half the size of this [the small room where the interview took place]; and they were quite posh. The seats, and the screen, and the projectionist up back, and a place for the secretary and such. It was well organized. I would say, only at a guess, a quarter of the things, a third of the things, had to be done over. Not all done over, but scenes. I don't know that any important scene was ever passed without some work on it. I don't know that any animator ever presented a scene to a director—I'm talking about Snow White now—that didn't have some corrections. And if the director couldn't find them, when Walt saw a sequence he would find them, and all the things to be done over. That's how good pictures are made.

What would be the nature of these corrections?

Almost anything. Grumpy wasn't grumpy enough—his actions didn't fit the force of the dialogue. The pre-scored [that is, recorded in advance of the animation] dialogue was shouting and forceful, but Grumpy just didn't seem to be portraying in his expressions and actions that piece of dialogue. Or it might be the dwarfs' dance, where they're all dancing around with Snow White. They weren't happy enough, they weren't bouncy enough, they weren't expressing the feeling of the music. Things like that. Or when Dopey got up on Sneezy's shoulders and danced around with Snow White, he wasn't silly enough. These corrections go way beyond the simple mechanics of animation. The best of animators, of course, would have to do things over, which was no stigma to them.

Would you ever have cases when the layouts and the animation weren't working the way you'd planned? Say the lines of action were conflicting—would you ever have to go back one step and rework the layouts as well?

That would be rare. The reason is that the layout man sat in the room with the director. The director had a large desk area, and the layout man had his own little corner—large rooms, they were. We called them "music rooms," but they were directors' rooms. The director and the layout man would go over this sequence—three or four or five times—and the director would very carefully explain to the layout man exactly what took place, and when it took place—"when," relative to the other actions of the scene—where he entered, how he entered, what he did—climb a tree or fall in a hole, whatever, and over here, maybe, and over there—and the layout man would then make, promptly, a rough sketch with many positions where the character would be in the scene, just rough. The layout man knew the characters pretty well to draw them, not to animate them. So the layout man would—to the best of his understanding of what the scene was about—make two or three rough sketches and present them to the director, who was sitting there, maybe busy for the minute, but nevertheless available, and the director would go over them with the layout man, and agree or disagree on what the layout man had done—whatever the perspective was, was the character shown going far enough away and coming up in the foreground enough, and all that kind of stuff, until the layout man got the director's OK and was prepared to go into his final layout drawings. When he went into those, he pretty much understood, and the director very much agreed, that that was what was wanted.

Now, there usually was not a change, but there could have been a change when the animator came in to pick up the scene. Because, as I explained to you earlier, the animator had to be satisfied. There was no business of telling him to do it or else. The director's job was to sell the animator, the animator not necessarily really knowing what was good or not in ideas. Nothing against the animator; he was not a story man, he was not an idea man, he was an animator. But sometimes something would stick in his craw and he wouldn't like it, so we'd have to work it over and get it so he would like it. Change the timing on the exposure sheets, change the layout, do anything to get that animator satisfied and happy, when he left the room. I think you'll agree, in talking with any of the animators at the Disney studio, that when they left the room they were satisfied that the scene would work. So when they got back on the desk, and did the scene, and presented the rough animation to the director, then the discussion took place: "But you didn't do it enough." They had to follow the exposure sheet; the animator even helped to change an exposure sheet, if he didn't agree with the director's timing, and he didn't necessarily agree—that is, the key animators. They knew what they were doing; they'd say, "I don't have time to do that." And a director would argue, but nevertheless, he would cut out some action so as to give the animator the time he felt he needed. So, when the animator left the room, the fact is that he agreed that he had a good scene. So now he's returned with the rough animation of the whole scene—and the director said, "But you didn't do it the way we agreed." There were never any big arguments. The director would then act it out in some manner, and the animator would go back and make his changes, or get his assistant to make them—it didn't matter. When he came back the next time, it might be right, or something else might require changing. Then it went through the normal routine of in-betweening all the drawings and cleaning up, and into the other departments.

You mentioned timing—so an animator would say that there wasn't enough time allotted on the exposure sheet for him to make this particular action convincing?

Yes, an experienced animator would say that. The director had to time the whole picture, half-second by half-second, and he could of course always use a stopwatch—sometimes you would get a feel of a thing without a stopwatch for ten or fifteen seconds, but not very technical, close actions. He'd have to time those out. So there would be a discussion, and the animator would say, "Yeah, yeah, that's right, I didn't see it that way. Yes, I can do that." Or, "No, I can't do it." You'd certainly give him time to do it, or he would say, "Well, I can't do a scene like that. No wonder it doesn't come out, you wouldn't let me have the time!"

You and the other Disney directors were all former animators yourselves, weren't you?

We had to be. Not in our studio was there ever a director who wasn't an animator. No, the animator wouldn't have looked up to you—he wouldn't have trusted you. And you had to be a key animator; you couldn't be a junior someplace, you had to know what you were talking about. Naturally. He had confidence in you. Well, that's only proper, isn't it? We had confidence in Walt, the animators had confidence in the directors, that they knew what they were talking about, especially if the director would discuss and argue with them and work with them, to get the thing the way the animator thought it ought to be, so he would do it properly.

How did you become a director yourself?

The first direction I did was at Fleischer. How was it Walt picked me? I don't know. I don't know why the Fleischers picked me. I was an idea man, I always have been an idea man. Not necessarily the best idea man, but an idea man. I found myself writing and directing the "Out of the Inkwell" cartoons. From animation—which I did—to writing and directing. I must have had some executive ability, or I couldn't have handled the Disney operation, and I couldn't have later gone over to Rank. It must have been there, but I don't know how, except that the boss man must have recognized it. Why Walt ever picked me to direct Snow White when there were five other directors—I don't know. He told me that I shouldn't be in the business, on my first directorial job on shorts. That was Building a Building. Walt had the extra animators, and I suppose he saw a directorial ability in me—I say that humbly—so he gave me this story that was turned down by other directors and said that I was to direct it. This was my introduction to Disney direction, although I had directed before Disney. He didn't care about what I'd done before. But he wouldn't give me any of the key animators, the guys who could animate. He gave me these little, junior fellows. He said, "Hell, Dave, you've worked with juniors as supervising animator, you can work with these fellows." Well, there was a lot of personality stuff, and how do you get it out of juniors? Anyway, when the picture was previewed, I felt happy, because I happened to have counted the number of laughs in the picture, because it was my picture. Never mind the number, it was up there—actually, twenty-one. I was very happy—happy for the studio, not for myself. The next day, Walt came into my room, and he stayed through noon hour—about an hour and a half—and told me where I should have been, instead of in an animation studio, and how did I ever think I could direct. This is true: Walt isn't here to defend himself, but I assure you it was true. He knocked me down until I was lower than a snake's belly. I don't know why he did it, because I know the picture was all right: I heard the audience at the sneak preview. A very peculiar man, Walt was. But I took it. I took it, and before long I was directing Snow White [laughing]. Don't ask me how I got it.

I must tell you, a very funny thing happened. We had a meeting on Snow White, on one of the sequences, and the director is always in on a sequence when it's finally getting ready to be delivered, and they had an action with one of the dwarfs moving around the room, and you had to work to a certain length—this was working to music, and had about thirty seconds for this particular action. Walt was a marvelous pantomimist, a marvelous actor. If you said it to him, he would grump and walk away, but he was. And, of course, when he would get one of his expressions on his face with an animator, you'd better get it on the screen, which you usually did. He had a rubber face, it seemed to me. Anyway, I couldn't see the action getting completed in the time allotted. I said—because we always deferred to Walt, never mind how many other people were in room, you worked with Walt, and talked to him, and told him it didn't work, you didn't tell somebody else—I said, "Walt, the animator can't do it in that time." He said [imitating Disney's grumpy voice], "Hell, yes, Dave, you can do it in that time." He got up and did it again—very good acting. I said, "Well, it looked too long to me, Walt." He didn't know it, but I had a stopwatch hidden in my pocket. A dirty trick. And I said to him, "Walt, do it once more for me, will you, please?" "Oh, sure." Now, it was supposed to be done in thirty seconds—not thirty-two seconds—and he'd get up, and he'd go all through it—marvelous stuff, you know. Lots of action in it, lots of things to be done. And he got all through and he said, "There! You see, there it is—thirty seconds." And I pulled this stopwatch out, which I had started with his acting. I should never have done it. I looked at my watch and I said, "That was fifty-five seconds, Walt." I learned a lesson. He didn't like that kind of thing, he didn't like that at all, no. He had an eyebrow that went up and helped to part his hair, and it went up, and the other one went down. He had a very disturbing frown. He didn't say a word. He just turned and stomped out of the room. He hadn't said anything. What was there to say?

He was a funny man. You didn't usually cross him. You didn't tell him he didn't know what he was talking about, ever. We knew better than that. But we did do things behind his back that he didn't want done, in order to get a job done.

When you first came to the Disney studio, I guess in '29 or '30...

January 1930, the last of the month.

You've already mentioned the synchronization of the sound, but what other things was Disney doing that struck you as different from what you'd been exposed to before?

The Movieola, the pencil tests. You saw a negative, you understand that; it was a negative delivered to you in a loop, for your scene. The scene might be four, five, six, eight, ten seconds. Your loop went around through that Movieola. The Movieola was set at twenty-four [frames] per second, although you could run it very slowly and back it up, back and forth, back and forth. That was the innovation, and that was the thing that allowed the animator—and allowed Walt—to see what the animator was going to put on the screen, so the animation didn't get all the way through production before he could see it.

They were already making pencil tests when you went to work there?

Yes, I remember standing by the hour, looking at tests. Just one little bull's-eye, you know. The damned thing stood up so high, and you put your foot on the pedal; that's all they had.

What really distinguished Disney from the New York studios was the striving for personality in the characters. Were you conscious of that when you came to Disney, was it already in evidence?

It was not in open evidence, but such a thing as what Walt was striving for grew within him and the animators—a unity of development, of a desire for the better, for the very best obtainable. Walt, of course, was the spirit in back of it all, when he could tell the front office, "You get the money, we'll make the pictures." You never heard that before, not in the cartoon business. It was always, "Yes, sir, we'll do it for thirty-five hundred dollars"—and you'd better.

I've always heard the general statement that his story mind was what set him apart.

Yes, this is true. Well, that's part of what his genius was, [but] he had it more than there. He intuitively knew pretty much—didn't make many mistakes—what was right and what was wrong. Like a woman, who doesn't reason the way a normal executive would reason about something. He worked by intuition a lot.

I've heard that he would come into a meeting, where say nineteen or twenty people were working on a problem, and he would suddenly reach out and pull the solution out of the air.

It wasn't quite that spontaneous. I would say that whether it was a good solution or not, if Walt decided it was, that was the end of the conference. That's fairly stated. So, I wouldn't say that was necessarily true. I've seen us all struggle by the hour, by the week, with Walt in the meetings, struggling over solutions. He didn't get them that easy. But he did have a good memory, which helped him, and also he used intuition.

He and I used to belong to a riding group out here in Santa Barbara, called the Rancheros Visitaderos, and every May they rode for a week up over the mountains and stopped at different ranches—all men, stag [according to records in the Disney Archives, those outings took place in the late thirties]. He would ride along with me—these were long rides, up from Santa Barbara over to the Santa Ynez Valley. He would talk at me, all the time, riding along, what we should do on some picture or problem, and how we should do it, and I got so full and so confused, with his changing his mind, that I eventually—the second or third day starting out—would hide out, behind the big oaks, with my horse, until he went on down the trail with some other Rancheros, then I'd go along merrily, to keep away from him. He was wearing me down; he didn't know anything else, he couldn't talk anything else, but that studio. When [he was] at home, he'd go over to the studio about every night, you know, and look through animators' drawings. ...

Walt never praised; I don't ever remember him praising me or anybody else. I don't want to be unjust with the man, [but] I don't remember him ever saying, "Gee, you did a fine job," slapping you on the back. Never that. Never that. And he prohibited us from looking at other studios' pictures; I mean to study them, in the early days. We'd come in and say, "Oh, boy, we saw a lousy"—whatever picture. "Let's get a print to look at." Walt said, "Look, don't go looking at that kind of stuff. Just look at good stuff. If you find good stuff, let's look at it, but don't look at bad stuff." We were so happy to be so much better, but he took us down, he didn't care about that.

So, if you didn't get criticized by Walt, that was your praise, more or less?

Well, yeah. The theater was our—and his, too—criterion. It was our answer. If it wasn't good, he didn't have to tell us. We knew it, you could tell it. I'm talking about the key men now. He didn't have to scold people. If any scolding was to be done it was in the sweatbox before the preview. At the time of the preview, the die was cast, and he stood responsible with everybody else for what was on the screen.

[Posted May 2003; illustration replaced, 7/31/15]]