ESSAYS

A "Golden Age" Comic Book Script

By Michael Barrier

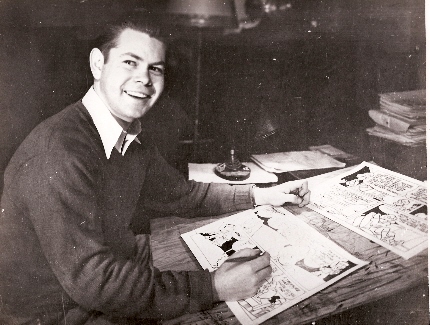

Last June, I wrote about the death of Roger Armstrong:

Roger was one of comic art's true good guys. I first wrote to him forty years ago this summer—he was one of the very first animation/comics people I approached—and we sustained a lively and tremendously enjoyable (for me, certainly) correspondence for a number of years. I saw Roger on my first two trips to Los Angeles, in 1969 and 1971, and on the first trip I acquired one of his watercolors, a voluptuous nude, which hangs now in my home.

I wrote to him because I'd learned that he drew many stories for Western Publishing's comic books of the 1940s, the ones with the Warner Bros. characters in particular. ... I felt, and feel, a tremendous affection for those comic books of my childhood, and corresponding with Roger, and spending a little time with him, only increased that affection.

I've been spending some time lately with the letters Roger wrote to me in 1967-68. He was "present at the creation" of Western's Los Angeles office, which was better known then as Whitman (to add to the confusion, the comic books themselves came out under the Dell label), and his letters are packed with details about what it was like to work on Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies Comics, Walt Disney's Comics, and other Disney and Warner Bros. titles. Roger mainly drew, but he also wrote a lot of stories, illustrated by himself and others. He'd saved many of the comic books he worked on, but they'd been stolen along the way. It was my great pleasure to send him dozens of comic books with his stories, along with early mimeographed issues of Funnyworld. The comic books triggered a flood of memories that he shared with me in his letters.

In one of my early letters, I asked Roger about the nature of the scripts he worked from (and sometimes wrote himself), and he replied: "Somewhere, in storage, I have at least one old Porky Pig manuscript from the 1940's, a Chase Craig opus. It kills me to think of it, but I always just threw the script away after completion of a story...well, not immediately after, but, say, after they began to pile up around the studio and I would want to get my drawing area neat, a phenomenon which happened once very two or three years about. At any rate, when (and if) I find it, I'm going it to you for your collection. So you will be able to see the way it was done."

In one of my early letters, I asked Roger about the nature of the scripts he worked from (and sometimes wrote himself), and he replied: "Somewhere, in storage, I have at least one old Porky Pig manuscript from the 1940's, a Chase Craig opus. It kills me to think of it, but I always just threw the script away after completion of a story...well, not immediately after, but, say, after they began to pile up around the studio and I would want to get my drawing area neat, a phenomenon which happened once very two or three years about. At any rate, when (and if) I find it, I'm going it to you for your collection. So you will be able to see the way it was done."

If Chase Craig's name rings a bell, that's probably because he was an editor at Western for decades, supervising most notably Carl Barks's Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge stories. Before that, though, he was a cartoonist and then a writer for many of Western's titles; Roger recalled that he and Craig wrote and drew all of the second issue of Looney Tunes by themselves.

Roger located and sent me Craig's script a few months later, in February 1968. "The enclosed is a typical script of those days," he wrote. "Occasionally, the dialogue would be typed in and, in the case of a non-artist writer, the description of the action would be typed underneath."

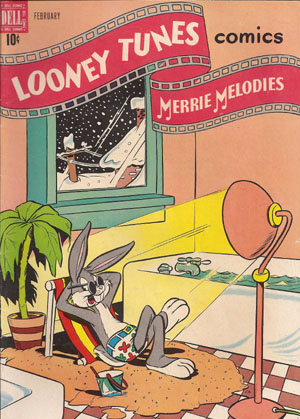

The script, date-stamped June 1948, is for the 12-page Porky Pig story in the February 1949 issue of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies Comics ( the cover of that issue is at the right). There was a 12-page Bugs Bunny story at the front of the book, and the remaining 24 pages were divided among eight-page stories of Mary Jane and Sniffles, Henery Hawk, and Elmer Fudd. No ads; back in the day, you got 48 pages of comics for a dime.

The script, date-stamped June 1948, is for the 12-page Porky Pig story in the February 1949 issue of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies Comics ( the cover of that issue is at the right). There was a 12-page Bugs Bunny story at the front of the book, and the remaining 24 pages were divided among eight-page stories of Mary Jane and Sniffles, Henery Hawk, and Elmer Fudd. No ads; back in the day, you got 48 pages of comics for a dime.

I don't remember being in the least concerned, when I was reading Looney Tunes as a kid, about how closely the comic-book characters resembled their screen equivalents. For me, and for many other readers in those long-ago days, the Warner characters were comic-book characters above all. That was long before the Warner cartoons started turning up on TV, and we simply didn't see enough cartoons in the theaters to think of Bugs & Co. as movie characters who also made print appearances. I saw a lot of movies when I was a kid—I was lucky enough to grow up in a time when my parents thought nothing of letting me ride the bus downtown to see a movie when I was ten or eleven years old—and although I remember many of the live-action features I saw, it's hard for me to remember the shorts. Certainly I saw very few Warner cartoons.

Reading a comic book like Looney Tunes now, and knowing a great deal more about the movie cartoons than I did in 1949, I'm struck by how much the comic books diverged from the screen originals. Characters like Sniffles and Henery Hawk were much more prominent in the comic books than they were in the cartoons; Mary Jane was purely a comic-book character. All of the Looney Tunes characters took part in stories that usually had little in common with anything that happened in the animated shorts.

The same was true in Western's comic books with characters from other studios, like Donald Duck and Woody Woodpecker. That's why those old comic books were so much better than more recent efforts that reflect a greater awareness of the animated cartoons. Good animation stories and good comic-book stories are very different, and, fortunately for those of us who were reading them back then, Roger Armstrong and Chase Craig and their colleagues were concerned only with making good comic-book stories, not with how closely they were tracking the animated versions of the characters. If none of the Warner Bros. comic books quite equaled the best work of Carl Barks or Walt Kelly, there was solid, unaffected storytelling in a lot of them.

And here, to give you a glimpse of how those comic books were being made sixty years ago, is that Chase Craig script that Roger Armstrong sent to me in 1968, each page accompanied by the published version that Roger drew (and, as you'll see, often restaged). You can click here to go to the first page, and from there to the remaining pages, or you can go to any of the twelve pages by clicking on the links below:

One Two Three Four Five Six Seven Eight Nine Ten Eleven Twelve

To read more about Roger Armstrong, please visit this affectionate tribute by Mark Evanier.

[Posted January 26, 2008]