ESSAYS

| Story sketches from early in work on Dumbo, as published in The Art of Walt Disney by Robert D. Feild (1942). |

The Mysterious Dumbo Roll-A-Book

By Michael Barrier

[Click on this link to go to a Feedback page about this article, including a comment by Andrew Mayer, the son of Helen Aberson Mayer, co-author of the original version of Dumbo.]

When I wrote in a January 14, 2010, post about the history of the black crows in Dumbo, I reached back as far as the 102-page treatment that Joe Grant and Dick Huemer submitted to Walt Disney in the early months of 1940, in installments. But Dumbo's history goes back further than that, as Huemer himself acknowledged in his interview with Joe Adamson, part of which I published in Funnyworld No. 17. Adamson asked, "Where's the story that Dumbo comes from?" and Huemer replied:

I never saw it, but they say it was on a little strip that was given away on a cereal box. Or maybe it was even printed on the outside, I don't know. But it had the basic elements of the story: the little elephant who had big ears, was made fun of, learned to fly, and was redeemed. All in just a few panels. Well, we took it from there, had a few story meetings, then Joe Grant and I wrote it up a chapter a time and submitted it to Walt. He used to come down and say, "That's coming along good,. We'll make it!"

Then we got sketch men and story men and went to work and put together what we call a Leica reel. A Leica reel was a way of presenting a storyboard with the individual pictures on a filmstrip that was run through a Leica projector. You'd flip over a picture and talk about it, then flip over the next. ...

This was how we often held a story meeting. Sometimes we had rough Leica reels in pencil, and later we would make a color reel.

Adamson: When you first got Dumbo, what form was it in?

Huemer: Somebody had started working on it and there were quite a few sketches that I remember, but no storyboards yet. Mostly talk, getting together with Walt, and taking notes, and studying them. Dumbo was put aside a while to concentrate on another picture, I suppose, then Joe Grant and I picked it up.

Although I talked with Joe Grant about Dumbo on several occasions, I don't seem to have asked him about that "little strip" that Huemer mentioned. He did speak about it to the New York Times, though, in 1999, six years before his death at the age of ninety-six, and he said that he had seen the "strip," even though Huemer hadn't. Grant said, in the Times' paraphrase, that the "story and about a dozen illustrations appeared on a small, short scroll that was built into a box. ... Mr. Grant said he remembered seeing only one 'Dumbo' box-and-scroll, the one that was used in making the movie. 'It was sort of a little novelty idea, he said. 'As you rolled this little wheels on top, the pictures would appear like they would in a film.'"

That original version of Dumbo was copyrighted in 1939 as a "Roll-A-Book" by the company of that name. The Copyright Office's card catalog includes a registration for the book that reads as follows:

Dumbo, the flying elephant

Roll-a-book publishers, Inc.

550 Erie Blvd., W., Syracuse [New York]

Publication date: 4/17/39

Registration date (and copies received date): 4/29/39.

The authors' names are listed as follows, in brackets: [Pearl, Helen, and Pearl, Harold].

Helen Pearl was born in Syracuse on June 16, 1907, as Helen Aberson, the daughter of Russian immigrants. She and Hal Pearl married on February 14, 1938. Aberson wanted the marriage kept secret, perhaps because she was almost seven years older than Pearl, but it was announced two days later in the Syracuse Journal, after Aberson's father, a retired cigarmaker, died suddenly. I haven't yet located a record of the divorce, but according to "The Long Flight of Dumbo," an extensive article by Dick Case published in the Syracuse Post-Standard on May 5, 2002, the marriage lasted little more than a year, until the summer of 1939, just long enough for the Pearls to collaborate on Dumbo, the Flying Elephant.

Aberson graduated from Syracuse University's School of Speech in 1929 and then worked in New York City doing what an alumni questionnaire quoted by Case calls "social service work" before she returned to Syracuse in 1933 "to direct children's dramatic activities at a nearby children's camp" and to work for the city's recreation department. "I left in August 1937 to do radio work for a local concern," Abserson wrote in the questionnaire; she was evidently an on-air personality. Aberson said she met Pearl in October 1937, around the time he was hired to manage the Eckel theater: "He's an ex-New York American newspaper man who had come to Syracuse as an exploitation and publicity man for United Artists. He stayed on after being offered the managership of a downtown Syracuse theater." At the time of the wedding Pearl was managing the Paramount theater, which was under the same ownership as the Eckel..

When she died on April 3, 1999, at the age of ninety-one, Helen Aberson was living in Manhattan, had been married to a businessman named Richard Mayer since 1944, and was known as Helen Aberson Mayer. The New York Times, reporting on her death, did not mention her marriage to Pearl. The Times identified her in a headline as "Dumbo's creator." It also said—citing her son, Andrew Mayer, as its source—that Pearl illustrated the story rather than wrote any of it, even though he was listed as its co-author and there's no reason to believe that he drew any illustrations.

Pearl himself, writing as "Hal Pearl" in a bylined article in the Miami Daily News for November 2, 1941, described how "we" had written Dumbo, inspired by the example of Munro Leaf's Ferdinand (also made into a cartoon, of course, as the first Disney short to be based on a licensed property). Pearl, who was living in Miami at the time, never makes clear in his piece whether he is using the authorial "we" or is referring to his actual co-author, who goes unnamed.

A few days after that Miami Daily News article appeared, Pearl was en route to the West Coast when he was interviewed by the New Orleans Times-Picayune, for an article published on November 13, 1941, under the headline, "'Dumbo' Creator Stops Here While Going to Coast." The article's summary of Pearl's career and the writing of Dumbo is clearly inaccurate, although it's impossible to say whether Pearl or the newspaper was most at fault:

Mr. Pearl wrote the story of his woeful circus elephant with the too-large ears four years ago when he was a columnist and amusement editor for a Miami, Fla., newspaper. He intended it to be a story for children, but in the course of his efforts to sell it, the script was shown to Disney, who purchased it in 1939.

Pearl was traveling with "Mrs. Pearl," who is otherwise unidentified but was presumably the woman whom the Florida Marriage Index shows as marrying Hal Pearl in Dade County in 1941.

Pearl died on December 17, 1975, at the age of 61 (he was born on June 8, 1914). His obituary in the New York Times is at odds with that Times-Picayune article—and certainly more accurate—since it says he "began his newspaper career with The New York Journal-American and became assistant drama editor. He moved to Florida in 1940 to join The Miami News, and at his death had been with The Hollywood Sun Tatler for eight years, serving as amusement page editor and columnist." But the Times obituary, like the Times-Picayune interview, makes no mention of Pearl's roughly two years in Syracuse, from 1937 to 1939, or his marriage to Aberson.

There's probably no way to determine whether it was Aberson or Pearl who deserves the most credit for "creating" Dumbo. By the time the film appeared—which was when the question of authorship got interesting—Aberson and Pearl were divorced, and Pearl was obviously in no mood to share the credit. Aberson had the last laugh, though, by outliving her younger former husband by more than twenty years and garnering a much longer New York Times obituary than his. Neither Aberson nor Pearl ever published another book.

As to what a Roll-A-Book looked like, Peter Hale provided an answer more precise than Joe Grant's description by sending me a link to the patent for the Roll-A-Book. This is the first of the five pages, illustrating the "display device."

Peter Hale writes:

Funny, but I'd always pictured it scrolling from right-to-left, landscape-style, rather than up—but then this way the format looks more like a book.

Patent applied for November 2, 1938, granted June 20, 1939. Even assuming the publishers had started production before the patent was applied for, it would seem they couldn't have published many Roll-A-Book titles before Disney picked up Dumbo.

That is correct. There was only one Roll-A-Book, called The Lost Stone of Agog, published before Dumbo; according to its copyright registration, it was published by Roll-A-Book on November 28, 1938. An advertising circular for that book described it as "a fast moving adventure story packed with mystery and surprises [and] crammed with heroic exploits." There were fifty pictures in "Roll-A-Color" (I have no idea what that was) and twelve thousand words. That first Roll-A-Book sold for fifty cents.

Roll-A-Book Publishers was incorporated in October 1938, just a few weeks before its first title was copyrighted. The company's aim, as the certificate of incorporation put it, was to "conduct a general business in printing, bookbinding, general publishing, manufacture of specialties and advertising novelties." The three incorporators were Everett Whitmyre and Mildred V. Whitmyre of Syracuse and Fred H. O'Hara of Norwich, New York, a small city southeast of Syracuse. Whitmyre, a native of Schenectady, New York, was an advertising man; Mildred was his wife. They had lived in Detroit and Utica, New York, before moving to Syracuse. O'Hara was not only president of Roll-A-Book Publishers, but also, since 1925, president of the Norwich Knitting Company.

It seems likely that Everett Whitmyre came up with the idea for the Roll-A-Book (and so is identified by the patent as its inventor) and that O'Hara put up most if not all of the money. There's evidence for that in, of all places, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt's "My Day" column for May 12, 1939, which mentions Whitmyre and refers unmistakably to Roll-A-Book, if not by name:

I was running through my mail last night and I came across a most amusing letter from a gentleman, Mr. Everett Whitmyre, who said that he was sending me a new invention in the way of children's books and, though I did not know it, I was partly responsible for his success. He had been trying to sell his idea and had become rather discouraged when he happened to go up in the elevator with me in an office building in New York City. Because I smiled and looked cheerful, he took heart again, got the money to finance his undertaking and is today employing a number of people. These books are light to hold and, as you read, you turn a little button and the book rolls up a page at a time. So, if you put it down, there are no pages to blow and make it hard for you to find your place again.

Although Dumbo, the Flying Elephant had been copyrighted by the time Mrs. Roosevelt's column appeared, Whitmyre had probably sent her The Lost Stone of Agog. Two libraries list The Lost Stone of Agog in their holdings in the WorldCat database, but there are no listings for any other Roll-A-Books. The galley proofs for two more Roll-A-Books are part of the Helen R. Durney Papers at Syracuse University, but there is no reason to believe that either was ever published, in the sense of being generally available to the public. One book would have been called Movie Riddle Quiz; the other galley proofs are for Roll-A-Book No. 2, Dumbo, the Flying Elephant.

Those galley proofs, and Helen Durney's preliminary drawings for the Roll-A-Book's illustrations, miraculously survived for more than thirty years after Durney's death, until Dick Case found them and placed them with the university's library. They are apparently all that remain of Dumbo in its original form, the story as written by Helen Aberson and Hal Pearl. The Walt Disney Archives had no copy of the Roll-A-Book version when I was doing research there in the 1990s, and Dave Smith, the Disney archivist, told me in 1997 that there was no copy in the company's "main files," either; those are the files of continuing legal significance, and as such have always been barred to researchers. Although the Copyright Office's card file shows that copies of the Roll-A-Book were submitted on April 29, 1939, it's not at all clear what those copies were. Were they dummies assembled purely for the sake of the copyright registration? If that was the case, did the April 17 "publication date" have any meaning? Or were a few copies actually prepared for sale? If so, none seem to have survived, in the collections of the Library of Congress (of which the Copyright Office is a part) or anywhere else. The Dumbo Roll-A-Book is a "mystery book" that no one seems to have seen, at least not since 1939.

The story told in the Dumbo galley proofs is essentially another version of "The Ugly Duckling," and much simpler and cruder than the eventual film version. Dumbo is not a baby elephant, but rather "a midget elephant whose ears were EXTRA BIG and EXTRA PINK." He botches his one appearance in the big top, when he falls off a box while trying to balance a big rubber ball on his trunk, but there is no general catastrophe. He is then befriended by a robin named Red, the original story's equivalent of Timothy the mouse. When Dumbo tells Red that he wishes he could fly away from the circus, the robin takes him to "Wise One," an owl, to find out if that is even possible. The owl recognizes Dumbo's ears as a potentially fine pair of wings, and under Wise One's tutelage Dumbo soon learns to fly. He keeps his newly acquired skill a secret until the circus comes to Madison Square Garden in New York. Just after all the other elephants have entered the ring, he flies into the arena, triggering general astonishment, followed by universal acclaim.

Helen Durney was a Syracuse artist who was, at the time she made her Dumbo drawings, on the staff of the Museum of Fine Art in Syracuse. Durney's drawings (none of which I can reproduce here because Syracuse University requires payment for such use) are conspicuously lacking in charm. Dumbo's trunk is flaccid and appears to have been pasted on his face, and his eyes are small and beady. If, as seems likely, her finished illustrations for the Dumbo Roll-A-Book were equally questionable, it may have been the illustrations' characteristics that led to the story's coming to the Disney studio's attention, through a roundabout route.

Walt himself spoke of the story's origins in an interview with the New York Sun published on October 21, 1941, just after he had arrived in New York at the end of his South American trip and just before his version of Dumbo had its New York premiere on October 23. According to the Sun:

"Dumbo" was originally a story by Helen Aberson and Harold Pearl, which the studio was asked to illustrate. Disney read the tale, saw picture possibilities, bought it, and proceeded to expand the original idea. The central character, of course, is still the little circus elephant who thinks his ears are much too big. Instead of consulting a bird, however, he now goes for advice to a mouse, a kind of a Country Cousin mouse instead of a Mickey Mouse.

| Everett Whitmyre, inventor of the Roll-A-Book in which Dumbo made his debut, was photographed in 1947 at the wedding of his daughter, Arlene Whitmyre Stewart. Photo courtesy of Jay Stewart, Everett Whitmyre's grandson. |

That sounds like an abbreviated version—whether abbreviated by Walt or the Sun, it's impossible to say—of a more complex negotiation. In any case, if Fred O'Hara, Roll-A-Book's president, was dissatisfied with Durney's illustrations, as he might very well have been, it would have been natural for him to think of Disney as a source of better ones, for the reason stated in another newspaper called the Sun, this one published in Binghamton, New York. The Binghamton Sun wrote on November 1, 1941, a few days after Dumbo's premiere, about Roll-A-Book's sale of Dumbo to Disney:

After purchasing the story, originally known as "Dumbo, the Flying Elephant" for the purpose of printing it in book form, Mr. O'Hara sold the picture and publishing rights to the famous artist. The Norwich man has had a business and personal acquaintance with Disney for several years.

The nature of that acquaintance was summed up by Cecil Munsey on page 128 of his 1974 book Disneyana:

In the small town of Norwich, New York, Mickey Mouse worked another of his merchandising miracles. In 1932, most of Norwich's employable citizens drew their salaries from the Norwich Knitting Company. Immediately following a shutdown of the textile mills, the Norwich Knitting Company signed a contract to put Mickey Mouse on sweatshirts. Like the Lionel handcar and the Ingersoll wrist watch, the Norwich sweatshirts became a big seller. By 1935 over one million sweatshirts a year were being sold, and one-third of Norwich's population was making enough money in overtime alone to support their families.

Norwich Knitting made other Disney-licensed products besides sweatshirts; a Web search quickly turns up a page devoted to the "Mickey Mouse Undies" in the Kansas Historical Society's collection. With such powerful evidence of the Disney cartoons' popularity so close at hand, O'Hara had every reason to hope that Disney might be interested enough in Dumbo to provide illustrations, or to buy the rights to the book itself.

(Durney, the Dumbo Roll-A-Book's illustrator, had invoked Walt's name in a three-page handwritten "Promotion Plan for Dumbo the Flying Elephant," probably written early in 1939, that is part of her papers at Syracuse University. The "Plan" called for the promotional effort to begin in the Syracuse area—with an anticipated sale of ten thousand copies there, a highly ambitious figure—and radiate out over several months to the rest of country, with the culmination of the campaign in California. There, Durney wrote, "Artist—thru friend who is ex. of Fox Films and in turn a friend of W.D. would have excellent introduction to Mr. Disney who would see and meet Dumbo." Durney seems not to have been aware of the Norwich Knitting connection.)

As to exactly how Disney came to buy the story, the best evidence is probably what Milt Gray and I were told by John Clarke Rose.

As to exactly how Disney came to buy the story, the best evidence is probably what Milt Gray and I were told by John Clarke Rose.

A native of the San Diego area, Rose was a commercial artist in New York City and then worked for two advertising agencies; he oversaw Procter & Gamble's advertising on such early radio soap operas as Vic and Sade. He joined the Disney story department in 1936—he told Milt he met Walt at a party—and according to a 1961 resumé he was at the time of Dumbo the "Story Editor and Story Research Director for all Disney productions, both features and shorts." Those titles may have been somewhat inflated—Dick Huemer once wrote to me of Rose's "fantastic displays of misdirected energy"—and Rose himself said, "I think I was generally known on the lot as the manager of the story department. ... Walt considered me the head of the story research department, as the studio grew." But there is no reason to doubt that he had a great deal to do with Dumbo's becoming a Disney property. Rose wrote to me in March 1978, after reading Huemer's memories of Dumbo in Funnyworld No. 17:

I was also amused by my old friend Dick Huemer's uncertainty over Dumbo's origin. As the guy who recommended that delightful story to Walt (after I found it serving to demonstrate a new children's novelty item, about to come on the market and called "Roll-A-Book"), I could fill in the background that Dick didn't know about. That Roll-A-Book product had a little handle for presenting an unwinding story through a cut-out window shaped like a movie screen—and the sample story was the basic plot-line of Dumbo, written by a schoolteacher in Buffalo [sic], as I recall. So far as I know the novelty product was never actually manufactured in any quantity, but for sure I promptly acquired the rights to that schoolteacher's little story when Walt shared my recognition of its possibilities.

Milt Gray interviewed Rose later in March, as part of the research for my book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, and Rose enlarged on his memories of Dumbo. The Roll-A-Book had come to his attention, he believed, through Herman "Kay" Kamen, the marketing genius who was in charge of licensing the vast array of Disney products; Fred O'Hara had no doubt made his Norwich Knitting deal with Disney through Kamen, and so he would have approached Kamen with Dumbo. John Rose said:

Kay had, I think, first been approached in New York by these people who were going to merchandise this new toy, a cardboard book-shaped business with this little wheel that wound up what was virtually like toilet paper, with the story unfolding in a frame-dimensional opening. To demonstrate this Roll-A-Book, they had to have a story, and I discovered this was a story we could damned well use, for production—forget the Roll-A-Book, per se. [The story] had been written by a school teacher in, I think, Buffalo [sic], and maybe somebody else was involved; but let's say it was an amateur, an imaginative somebody who I figured had been influenced by "The Ugly Duckling." And there it was, a beautiful story with a beginning, a middle, and an end. I probably told Kay that the Roll-A-Book per se was beyond my province, but that I damned well was going to propose [the story] to Walt. ... It was not a feature-length story; it was going to take a hell of a lot of padding—well, not padding, development, and extension, and imaginative input that I knew our guys, particularly my Otto [Englander], would provide. So when Dick [Huemer] said that he and [Joe] Grant had received something on which there had been preliminary work, it was Otto with whom I had consulted. ... I discussed Dumbo with Otto, and was delighted to find that Otto responded to it personally and was eager to go, for the creative opportunity that it afforded.

On June 14, 1939, Roll-A-Book Publishers and the Pearls sold Dumbo, the Flying Elephant to Walt Disney Productions. The terms of that contract are not a matter of public record, but Dick Case's article in the Syracuse Post-Standard quotes a 1993 letter in which Aberson says: "The terms were we would get $1,000 and royalties on the first 1,000 books of our original story, which amounted to a very small sum." That sum—and the prestige of a Disney association—probably outweighed any slim hopes of success with the Roll-A-Book version. The first paragraph of the contract was recorded with the U.S. Copyright Office on April 28, 1940, along with a separate assignment of the copyright on the book from Roll-A-Book to Disney.

Walt Disney's desk diary for 1939, which I reviewed at the Disney Archives in 1993, shows his first meeting on Dumbo as taking place in Joe Grant's Model Department on June 27, 1939—one week after the patent was granted to Roll-A-Book Publishers, Inc., less than two weeks after the studio bought Dumbo, and a little more than two months after the Dumbo, the Flying Elephant Roll-A-Book was officially published.

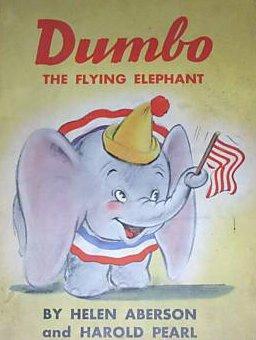

The desk diary shows Walt viewing a Dumbo Leica reel in "Joe's room"—Joe Grant's, that is—on August 29, 1939. That Leica reel was presumably made by someone other than Grant and Huemer when Dumbo was still envisioned as a short cartoon. (John Rose's remarks suggest that Otto Englander was in charge then, although I know of nothing that confirms his involvement.) The sketches at the top of this page, and the sketch of Dumbo with "Dr. I. Hoot," the owl psychiatrist at the left, date from this early phase of story work. All were published in 1942 in Robert D. Feild's book The Art of Walt Disney, as was the (presumably later) color sketch of Dumbo and Timothy Mouse.

The desk diary shows Walt viewing a Dumbo Leica reel in "Joe's room"—Joe Grant's, that is—on August 29, 1939. That Leica reel was presumably made by someone other than Grant and Huemer when Dumbo was still envisioned as a short cartoon. (John Rose's remarks suggest that Otto Englander was in charge then, although I know of nothing that confirms his involvement.) The sketches at the top of this page, and the sketch of Dumbo with "Dr. I. Hoot," the owl psychiatrist at the left, date from this early phase of story work. All were published in 1942 in Robert D. Feild's book The Art of Walt Disney, as was the (presumably later) color sketch of Dumbo and Timothy Mouse.

(As Huemer remembered, there was also at least one Dumbo Leica reel made after he and Grant began submitting their chapter-by-chapter treatment in January 1940. There's a reference to such a Dumbo reel in the 1940 desk diary; Walt saw part of a sequence as a Leica reel on June 24, when work on the feature was well under way.)

Disney's contract with Roll-A-Book and the Pearls evidently provided for publication of one edition of Dumbo the Flying Elephant under the Pearls' names. Getting that book into print was not entirely a smooth process, as evidenced by a letter I came across in the Disney Archives. On March 28, 1940—around the time that Grant and Huemer finished writing their treatment of the story—John Rose wrote to Franklin Waldheim, a Disney lawyer in New York, "that upon my return to the coast, I discovered that DUMBO is definitely shaping into a feature production; in fact, at this stage [it] is so different from the original story that we are afraid the Aberson book will suffer once the picture is released and subsequent book versions of the picture are published. ...

"The new studio-created DUMBO text will run considerably longer than [the book versions of] either SNOW WHITE or PINOCCHIO. ... DUMBO is approximately 28,000 words. Helen Aberson's original DUMBO runs approximately 4,500 words [the rough word count on the galleys]. Ours is not only over five times as long but it also includes many brand new characters and situations."

Rose wanted to renegotiate the deal with the authors and Fred O'Hara, with the apparent goal of reducing their royalty participation and their credit in the book, but he was not successful. The 1941 softcover book, the earliest book version of Dumbo in the Disney Archives' collection when I was there in the '90s, is titled Dumbo the Flying Elephant and shows Helen Aberson (who had by then dropped Pearl from her name) and Harold Pearl as the authors, with no mention of Disney on the cover. Published by Whitman—that is, by Disney's longtime licensee Western Printing & Lithographing Company—it bears two copyrights: 1939 by The Roll-A-Book Publishers, Inc., and 1941 by Walt Disney Productions; the copyright line is the only mention of Disney in the book.

Rose wanted to renegotiate the deal with the authors and Fred O'Hara, with the apparent goal of reducing their royalty participation and their credit in the book, but he was not successful. The 1941 softcover book, the earliest book version of Dumbo in the Disney Archives' collection when I was there in the '90s, is titled Dumbo the Flying Elephant and shows Helen Aberson (who had by then dropped Pearl from her name) and Harold Pearl as the authors, with no mention of Disney on the cover. Published by Whitman—that is, by Disney's longtime licensee Western Printing & Lithographing Company—it bears two copyrights: 1939 by The Roll-A-Book Publishers, Inc., and 1941 by Walt Disney Productions; the copyright line is the only mention of Disney in the book.

The 1941 book differs considerably from the 1939 galley proofs, the story having been reshaped to be consistent with what was emerging on the early storyboards at the Disney studio; the book's illustrations bear obvious similarities to the early sketches reproduced in Feild's Art of Walt Disney. Dumbo is a baby elephant in this version, and he causes the collapse of the elephant pyramid and is banished to the clowns. Dumbo leaves the circus in disgrace and is befriended by the robin, Red, who takes him to an owl psychiatrist, now called not "Wise One" but Professor Hoot Owl. When Dumbo tells him that he dreams of flying, the owl tells him to go ahead and fly. They climb to the top of a cliff and Dumbo flies, with Red's encouragement. Then he surprises everyone at the circus by flying when he leaps from a platform—again with Red's encouragement.

This interim version is stronger (and much less verbose) than the original 1939 version, but still not nearly as witty and economical as the film version. The differences suggest that the text was written, and the illustrations made by Disney artists, long before the book was published. (To see scans of the 1941 book provided by Alyssa Manley, click on this link or on the cover of the book, above.)

According to Dave Smith, the Disney archivist, a "book royalty card" shows that Disney received royalties on only 1,430 copies of the 1941 Aberson-Pearl book. (That card includes this notation: "This book was made to comply with contract.") Some unknown percentage of those copies included advertising on the back cover for Fern Furniture Company of Albany and Schenectady, and it seems likely that distribution was concentrated in Aberson's home region. Dumbo appeared in other book incarnations in 1941, all of them with much larger sales than the Aberson-Pearl book. Here are some of the figures from the Disney royalty cards, as provided by Dave Smith:

Dumbo of the Circus (Garden City) - 83,590

Dumbo of the Circus (K.K. Pubs.) - 402,179

Dumbo the Flying Elephant (Dell Fast Action) - 125,475

Dumbo (Whitman #710) - 209,000

Dumbo Big Little Book – 120,000

Aberson's son spoke after her death of her working at the Disney studio from 1939 to 1941, but that may have been based on a misunderstanding on his part. The Times quoted Dave Smith as saying that there was no record of her working for Disney, and I've never run across her name in any studio documents. Newspaper reports show that she did go to Hollywood in the fall of 1939—and spoke to Syracuse women's clubs about her visits to Disney and other studios—but the only record I've found of so much as an Aberson visit to the Disney studio is an entry in Walt's desk diary for November 19, 1941, a few weeks after Dumbo's New York premiere. The entry for 11 o'clock that morning reads as follows: "Mrs. Pearl (co-author Dumbo) Mr. Rose - First introduced Dumbo." That was about a week after Hal Pearl was interviewed in New Orleans, so they may have been in Los Angeles at the same time.

The Disney Archives doesn't have an exact publication date for the 1941 book, but, Dave Smith says, "one of our copies was checked out by Walt from the Studio Library on November 26, 1941." That was, curiously, exactly a week after he was scheduled to meet with Helen Aberson at his office.

In October 1943—by which time Fred O'Hara was Roll-A-Book's sole owner—the company changed its name to Characters, Inc. O'Hara died on October 2, 1955, soon after retiring as president of what was by then known as Norwich Mills, Inc. His New York Times obituary noted his involvement with several other businesses and nonprofit organizations, but it made no mention of Roll-A-Book. Characters, Inc., dissolved itself in 1970. At that time, O'Hara's son Edward H. O'Hara, who had succeeded him as head of Norwich Mills, was one of the three directors.

As for John Rose, after army service in World War II he was involved with a string of musical, radio, and television projects, culminating in the film that he wrote and produced for release by Warner Bros. in 1964: The Incredible Mr. Limpet, the combination animation/live-action feature starring Don Knotts.

[Posted February 4, 2010; revised, expanded, and updated, May 3 and 5, 2010, April 6, 7, and 13, 2011, and October 20, 2011]