ESSAYS

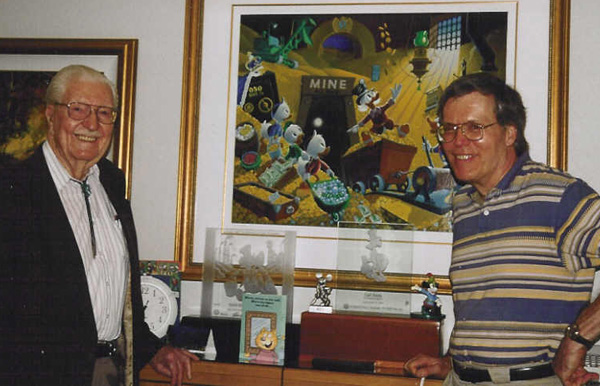

| Carl Barks in his study at Grants Pass, Oregon, on July 9, 1998. Photo by Michael Barrier. |

Thoughts on Carl Barks's Hundredth Birthday

By Michael Barrier

[Click here to read feedback about Barks and this essay.]

I last saw Carl Barks in July 1998, a few months after his ninety-seventh birthday, when my wife and I drove down to Oregon from Seattle with friends. We spent several hours with Carl, visiting him at his home and then taking him to dinner at his favorite local restaurant. He was in a buoyant mood; he had just put his lawsuit against his erstwhile managers behind him, through a settlement that was very much to his liking. But he was greatly changed, much slower and weaker, since we had last seen him, in 1991. He was not mentally impaired in the least, but to be as quick-witted as Carl Barks takes energy, and Carl no longer had very much of it. We left Grants Pass the next day doubting that we would ever see him again but hoping that he would live to see his hundredth birthday. Sadly, he didn't.

Our 1991 visit is a happier memory. Carl's wife Garé was still alive and well, and Phyllis and I had dinner out with the two of them. Carl was in a good mood then, too, exulting in the success of his paintings and the lithographs made from them. He insisted on picking up the tab that night, in a departure from our usual practice. We spent a happy hour or two after dinner in their den, talking about many things. We even laughed about the auto accident that put Garé in the hospital the night of their first date (Carl was driving—not too well, evidently), our laughter stimulated by the comically exaggerated cartoon Carl drew of her then, completely encased in a cast.

The next day, Phyllis and I drove out to Merrill to see the house where Carl was born on March 27, 1901. I took a lot of pictures and sent them to Carl, who returned them with abundant notes on what life was like there in the first decade of the twentieth century. He lived a hard, isolated life on that ranch, an isolation made all the worse by his chronic deafness. How miraculous that he had accomplished so much and lived so long—and how wonderful, it seemed to me then, that he was enjoying such great prosperity and renown in his old age.

Barks's oil paintings of the ducks were of course the source of that prosperity, and of much of that renown. Barks was a painter of ducks for about as long as he was an author of comic-book stories about them, and his financial rewards from the paintings were certainly much greater than those he got from his stories. For years before he died, it was reproductions of his paintings, and not panels from his greatest stories, that were ubiquitous as illustrations for tributes to him. The paintings, and the lithographs made from them, now command such prices that it is hard to imagine them hanging anywhere but in the homes of the very wealthy. Some of Barks's admirers, I understand, believe that the paintings have surpassed in importance the comic-book stories that gave them birth.

Which is insane. The paintings, most of them, are awful. The early ones are garish kitsch, the later ones more sophisticated kitsch (as Barks became more assured as a painter, he took more care with light, and he sensibly limited his palette), but they are all poor stuff. The early paintings, so often based on his comic-book covers, share some strengths with their sources—the shrewdly balanced compositions, the precise expressions—but the paint adds nothing. In the later paintings, more respectable as mere paint, the ducks are barely present, their faces and postures vacant as they never were in the comic books.

Cartoon characters are creatures of line. In most good cartoon art—Barks's above all—we see expression, attitude, pose; the characters are drawn in a way that encourages us to see those things, and not a physical reality. What would be preposterous about Barks's ducks as fully three-dimensional beings—think about those huge, exposed corneas—is a large part of what makes them so appealing as cartoon characters. A cartoonist may suggest that his characters are three-dimensional by the way that he turns them in space—whether on the page or on the screen—but to go beyond that, and give them not just weight but texture, is to risk destroying them.

Unless, that is, the cartoonist is prepared to see out the consequences of his choice, and to acknowledge that his cartoon characters, if they were real creatures, would be hideous monsters. Barks did not do that; when he painted his ducks he did not strive for either the hallucinatory clarity of a Bosch or the nightmarish indistinctness of a Goya. His ducks-in-oils are instead as vague—and thus as pointless, as paintings—as the ducks on the painted covers of many of Dell's "giant" Disney comic books of the fifties.

I was present in 1971 when Glenn Bray commissioned Barks's first painting of the ducks. I knew Glenn's intentions were of the best, but I could never quench the misgivings I felt about the paintings—as objects, at first, for the reasons I've just stated, and then out of concern about the paintings' ultimate impact on Barks's life and reputation.

I bought one of Carl's paintings that same May day in 1971—not a duck painting, but a landscape called "Hay Day." (It's "too cartoony," Phyllis says; I'm sure she's right, and I'm sure that's why I like it so much.) I didn't order a duck painting until I was somewhere around sixtieth on the waiting list, and I fell off the list as prices kept going up. In 1973, Carl and Garé gave Phyllis and me a small painting of Uncle Scrooge, as a belated wedding present; I treasure it, but I've never felt any regrets about not owning one of the larger duck paintings.

Carl was, I'm sure, fully aware of my coolness toward the paintings. I never felt that my skepticism about his oils strained our relationship (which began with letters in 1966). Inevitably, though, as the paintings and their spinoffs assumed a larger and larger place in Carl's life—and particularly after my book about him was finally published, in 1982—we were in touch less and less frequently.

When I saw Carl in 1991, it seemed that, financially at least,

the paintings had been an unalloyed blessing, but the events of

the succeeding few years, culminating in a lawsuit, changed my mind.

The Barkses were far from poverty-stricken before the duck paintings came along. When Glenn Bray commissioned the first of those paintings, they were living in a lovely, sunny home in Goleta, near Santa Barbara. No doubt the paintings and the lithographs made from them contributed marginally to the Barkses' comfort and security, but at a terrible cost to Carl's peace of mind in his last years. The paintings, the lithographs, the statuettes—all of them were a terrible mistake. How much better if he had never painted a duck.

A great deal of what I read and heard, in the weeks before and after Barks's death, left me disturbed and anxious about his future reputation. There was, for one thing, the anguished garment-rending on the Internet after Carl's terminal illness became known; it felt to me as false and worked-up as the mourning for the Ayatollah Khomeini. It was not the way to take leave of a ninety-nine-year-old man who had suffered terribly for months and who I am sure welcomed death when it finally arrived. Inappropriate breast-beating can all too easily give way to feelings of embarrassment, which can just as easily metamorphose into resentment of the presumed cause of that embarrassment. Were we really that upset about Barks? How annoying of Barks to make us look so silly. And what was so great about Barks anyway?

It is through such mental processes that magnificent creators can shrink in the eyes of people who owe them better. I fear that Barks is being diminished in other ways, too, not least by the sort of praise that stifles awareness of his most valuable qualities. Here is, for example, Lloyd Grove, in an admiring piece in the Washington Post: "It was as a storyteller—a children's book writer, if you will—that Barks was exceptional." R. C. Harvey opened a respectful, if distant, tribute in The Comics Journal by writing, "Carl Barks created stories for children."

The quick and dirty answer to the latter statement is to say, well, of course, he did—he was a comic-book artist and writer, for crissake. To suggest that it's important that, say, Harvey Kurtzman's or Jack Kirby's audiences skewed a little older than Barks's is to split some very fine hairs. All of the great comic-book creators wrote and drew for kids; what distinguished them was not the nature of their audience, but how well they managed to respond simultaneously to its demands and their own hearts' imperatives. By that standard, Barks need take second place to none.

When he is measured by his best work, that is. Here we come to the heart of the matter. What Grove was writing about, and what Harvey may have had uppermost in mind, were Barks's stories for Uncle Scrooge. It was as Scrooge's creator that Barks was most readily identified when he died, and for many years his Scrooge stories have been the ones most frequently invoked by his admirers. Those stories are children's stories, often very good ones, typically constructed with care so painstaking that it renders itself invisible (the very quality so sadly absent from Don Rosa's earnest Barks homages of recent years).

But the Uncle Scrooge stories are not Barks's best work. That honor belongs to some of the stories—no more than a few dozen in total—that he wrote and drew for Walt Disney's Comics & Stories and Donald Duck during a seven- or eight-year period in the late forties and early fifties. By then Barks had so thoroughly mastered the comic-book story as a medium that he could make full use of the many hard lessons life had taught him in his first five decades. His best stories are not children's stories—they are, instead, adult stories that children can follow easily even when they're very young, thanks to Barks's unfailing narrative clarity, and whose full meaning they can grow into, as so many of us did.

It was because Barks's temperament permitted him to meet the demands of child readers without flinching that he found himself liberated to explore vast reaches of human behavior. Uncle Scrooge in his earliest appearances was not just extraordinarily wealthy in a way that a child could immediately comprehend—diving like a porpoise through his cubic acres of cash—but he was also obsessed with riches in a way that an adult could recognize.

In story after story published in those years, Barks revealed an awesome understanding of how people's minds and hearts really work—and, typically, lead them astray. There was only rarely the sharp edge of real satire in these stories; Barks was clearly too skeptical about humans' capacity for salutary change to write stories that had any sort of agenda behind them. However bleak his stories' underlying message might be, though, it was always delivered with perfect comic timing and robust comic action. He took seriously his obligation to entertain the child reader.

I don't blame Barks because his work tailed off in the middle fifties, from the great to the merely delightful. Given the political climate then—and given Barks's acceptance, however grudging, of the editorial constraints he worked within, whatever they were at the time—it's hard to imagine that his stories could have retained their sharp edge throughout the decade. But certainly his editors were of no help. When Mark Evanier—solicitous, as always, of the industry's legions of conscientious hacks—writes in Comics Buyer's Guide that "[Barks's] editors—Chase Craig, in particular—had more to do with the end-product than some Barks fans seem willing to admit," he is all too correct. (To be fair, Evanier adds, "but not a lot more." I disagree: I think the impact of Barks's editors on his work was significant, and largely negative.)

What is already visible in Evanier's comments, and what threatens Barks's reputation now, is a familiar leveling impulse, one that tugs at our sleeves and asks rather plaintively that we tip our hats to, say, Paul Murry and Tony Strobl as well as Carl Barks, a leveling impulse that exalts the merely inoffensive at the expense of the best. Such an impulse comes easily to the adult "fan" in whom a child's natural lack of discrimination has hardened into resistance to intelligent choices. I suppose you can be a John Byrne fan as easily as you can be a John Grisham fan, but, especially where Barks's best stories are concerned, "Barks fan" is an oxymoron on the order of "Shakespeare fan." The artist's work is itself a sardonic commentary on the sort of mind that can embrace something uncritically.

There's no cure for all of these threats to Barks's standing as a comics creator, except to keep asserting the value of his best work (and hope that someone listens). I even despair sometimes of Barks's work ever being properly reprinted. So many of the reprints, like those in the Another Rainbow/Gladstone sets, seem harsh and glaring by comparison with the comic-book originals (not to mention travesties like the mutilated "Voodoo Hoodoo"). Photographing the comic books themselves doesn't necessarily produce better results, as the unfortunate reproduction in my own Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics proved. I can't think of a case in which I've seen a Barks story reprinted and thought to myself, yes, that's the right way to do it.

I used to worry a little about whether my strong feelings for what I regard as Barks's best stories were rooted too firmly in my childhood memories. I wondered if I treasured certain stories because I remembered so clearly where I was when I read them or even where I was when I bought the comic books. Re-readings have pretty much banished that concern. I think now it is much more likely that I remember those circumstances because the stories were so memorable, and not the other way around.

Still, there is probably something about having been "present at the creation" that gives Barks's stories a meaning for me that later readers can't share. Just as, I suspect, the groundlings who first heard Shakespeare's plays, in language that was wholly familiar to them, and the shopboys who bought Dickens's novels in installments and found themselves reflected in their pages, experienced those masterpieces in ways that later readers cannot. Which is not to say that those later readers won't experience Barks's stories in ways that mean just as much to them—perhaps struggling through the modern comic-book equivalents of corrupt Elizabethan texts—as mine did to me.

Having known and loved Carl Barks himself gives the stories an extra dimension for me, too, a not entirely positive one. I told Carl, in my last letter to him, that he had been a stronger influence for good in my life than any other man except my father. I felt with Carl, as anyone would with such a father figure, a tangle of emotions: a continual awkwardness, a sense that I was not doing enough, or was doing things in the wrong way, or was not saying the right things well enough or soon enough. My book about Barks—which should have been a source of joy to me—was instead a source of endless frustration and anger, thanks to a spiteful publisher and an incompetent typesetter. A reader who comes to Barks's stories now, without all that emotional baggage, can probably enjoy them with an untainted pleasure that I am no longer capable of.

I remember reading a collection of George Orwell's essays, years ago, when I came across a sentence that almost made me drop the book: "Like every other writer, Shakespeare will be forgotten sooner or later." I was reading that essay while returning from my first trip to England, and my first (and so far only) visit to Stratford-upon-Avon. The idea that Shakespeare could someday be forgotten was all but inconceivable—but of course it's true. It has to be true. And what is true of Shakespeare cannot be any less true of a great writer whose finest work was published on newsprint in lightly regarded magazines for children. The neglect of Barks's best work today is, inevitably, only the prelude to a lasting lapse of memory.

That's a sad thought, perhaps, but it gives birth to a happier one: how lucky we are to live in a time when Carl Barks's most wonderful stories have not yet been completely forgotten. They are still with us, nourishing the souls of those people fortunate enough to read them.

Goodbye, Carl, and thank you. Rest in peace.

| Carl Barks and Michael Barrier at Grants Pass, Oregon, July 9, 1998. Photo by Phyllis Barrier. |

[Posted May 2003 and (with additonal and larger illustrations) July 2014 and October 2018.