ESSAYS

75 Years of Duck Comics by Carl Barks

By Michael Barrier

This essay appeared originally in the souvenir book for the 2017 San Diego Comic-Con International.

In 1942, seventy-five years ago this summer, Dell published Four Color Comic No. 9, Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold, the first Donald Duck comic book with drawings by Carl Barks. The next year Barks began writing as well as drawing a monthly ten-page Donald Duck story for Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories. The first of many Donald Duck one-shots with Barks scripts and art, for stories sometimes longer than thirty pages, followed later in 1943.

In 1942, seventy-five years ago this summer, Dell published Four Color Comic No. 9, Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold, the first Donald Duck comic book with drawings by Carl Barks. The next year Barks began writing as well as drawing a monthly ten-page Donald Duck story for Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories. The first of many Donald Duck one-shots with Barks scripts and art, for stories sometimes longer than thirty pages, followed later in 1943.

Even though Barks never signed his comic-book work, he has for decades been all but universally recognized as the premier writer and artist for the Disney comic books. He was known first as the anonymous “good artist,” before admirers of his work uncovered his identity and began sharing it in 1960. He had achieved exalted status among comics fans by 1967, fifty years ago, which was, as it happens, the year when I wrote my own first appreciation of Barks’s work—the first such essay of its kind.

That piece, “The Lord of Quackly Hall,” appeared in my magazine Funnyworld, which was then a very low-circulation mimeographed effort. I was corresponding with Barks by 1967—I had written to him for the first time the year before, after taking months to work up the nerve—and my piece incorporated information he provided. “Quackly Hall” wasn’t entirely favorable, since I believed then (and still do) that the Barks stories of the 1960s were disappointing compared with the masterpieces of the late 1940s and early 1950s. Carl groused about the reservations I expressed in “Quackly Hall,” but only a little, since no one was a more demanding critic of his work than Carl himself.

I wrote about Barks’s stories repeatedly after that maiden effort, first for Don and Maggie Thompson’s fanzine Comic Art, and then in contributions to books. My bibliography of Barks’s work, published in installments in Funnyworld, was collected in 1982 in my book Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book, for which I also wrote an extended biographical and critical essay. More recently, I wrote about Barks at length in my history of the Dell comic books, Funnybooks.

In all of those books and essays, I reworked and expanded ideas I had broached in “The Lord of Quackly Hall.” I became aware, as I re-read Barks’s stories and then wrote about them in new pieces, that in “Quackly Hall” I’d neglected the central element in his work: his characterization of Donald Duck himself. But recognizing that neglect didn’t make curing it particularly easy.

Writing about characters Barks had created himself, like Gladstone Gander and Gyro Gearloose and even Uncle Scrooge McDuck, was essentially a straightforward task; those characters were clearly defined by what they said and did. Donald was different. He was never the same from story to story. He held a variety of different jobs, when he worked at all, performing some of them spectacularly well before plunging headfirst into disaster. He was more often foolish than sensible, and he was sometimes mean-spirited and jealous, but never quite beyond redemption. Writing about Barks’s Donald was so demanding because Donald was a perpetually moving target.

Writing about characters Barks had created himself, like Gladstone Gander and Gyro Gearloose and even Uncle Scrooge McDuck, was essentially a straightforward task; those characters were clearly defined by what they said and did. Donald was different. He was never the same from story to story. He held a variety of different jobs, when he worked at all, performing some of them spectacularly well before plunging headfirst into disaster. He was more often foolish than sensible, and he was sometimes mean-spirited and jealous, but never quite beyond redemption. Writing about Barks’s Donald was so demanding because Donald was a perpetually moving target.

And yet the different Donalds did not contradict one another. Donald was not the same from story to story, but he was a whole person in each story. Reading about Donald in Barks’s stories was like encountering a friend on different days, usually under very different circumstances, and being made aware of how fluid the human personality really is. (Donald was, of course, a duck in name only.) Much the same was true of Donald’s nephews, his indispensable auxiliaries, a chorus of three identical members whose most important role was to comment critically, as in the classical Greek model, on the action in the foreground, that is, Donald’s follies and triumphs.

It’s hard to exaggerate how radically Barks’s characters and stories differed in their prime from what filled most comic books. The other Dell comic books with talking animals, screen characters like Bugs Bunny and Andy Panda, could be superficially similar, especially when their writers and artists sent those characters on adventures in exotic places, but the characters were, compared with Barks’s ducks, little more than Halloween costumes.

There was in Barks’s stories no superficial continuity from one story to another, no cross-references; each story was a self-contained unit. What Barks did, instead of rely on such aids, was to depict a cartoon world in which characters, settings, and plots were all remarkably concrete and insistently plausible. He drew the broadest emotions with impressive precision; he treated with respect the kinds of stories—slapstick, farce, pulpish adventure—so often handled carelessly or contemptuously. It was the plausibility of the events of each story that permitted wide variations in Donald himself. Comedy was the only constant.

After Barks hit his stride in the late 1940s, his duck stories took their place among the very few comic-book stories that can be considered literature, and his Donald became one of literature’s great comic characters. The disciplines Barks observed, as he wrote and drew, permitted him to plumb emotional and psychological depths even though he was working away at a mid-century children’s comic book, an environment that was not hospitable to such achievements.

After Barks hit his stride in the late 1940s, his duck stories took their place among the very few comic-book stories that can be considered literature, and his Donald became one of literature’s great comic characters. The disciplines Barks observed, as he wrote and drew, permitted him to plumb emotional and psychological depths even though he was working away at a mid-century children’s comic book, an environment that was not hospitable to such achievements.

As this evolution continued, Barks’s stories separated themselves from other comic books, the superhero titles especially. Superhero comic books have always offered wish-fulfillment, sometimes crudely, sometimes with wit and sophistication, but the ruling idea is that the hero’s drab civilian identity conceals how special the hero—the reader’s surrogate—really is. Barks’s duck stories did not offer wish-fulfillment; instead, more than other comic books of any kind, they held up a mirror to life.

.

Great literary characters reveal more of themselves as we re-read plays or novels by the likes of Shakespeare and Tolstoy; something similar happens when we revisit the penetrating portraits by a painter like Velazquez. Barks’s best stories, too—which are of course combinations of words and drawings—yield up fresh insights into their characters when they’re revisited. Re-reading was in fact normal for comic books’ child readers when the stories were first published, because other sources of amusement were not yet overwhelmingly abundant.

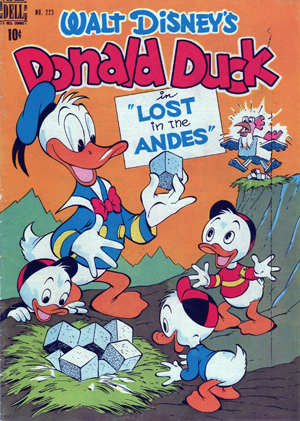

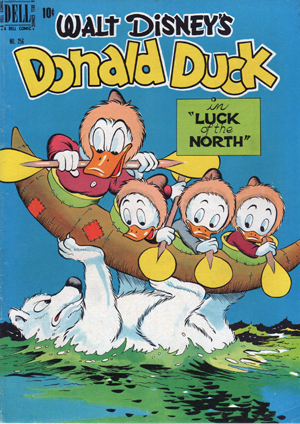

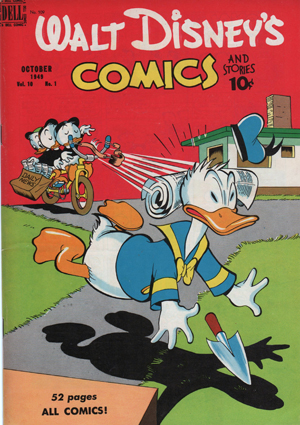

In my own case, I could not begin to estimate how many times I’ve read the Barks stories I love best, like “Lost in the Andes” and “Luck of the North,” both published in 1949, which may be, now that I think of it, Barks’s all-time best year. I recently read again the ten-page story from the October 1949 Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories, the first issue I received on the subscription to Walt Disney's Comics that was a ninth-birthday present. As I wrote in Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book, that "made it something special. Perhaps that was why I noticed that the ten-page Donald Duck story ... stood apart from the others.... I was very much aware of the specific California setting of the story, with, for example, its references to the Los Angeles aqueduct and desert hot springs."

The aqueduct enters the story because the nephews are trying to prove to Donald that their witching stick really can find water. When the stick tells the ducks to drill in the desert, they do so; Donald is trying to wean the nephews from their obsession, and he has attached what he calls a "power digger," one of Barks's wonderfully solid and authentic-looking tools, to the rear of his car. But when Donald does drill into water, it's by piercing the aqueduct.

As I failed to note in my book, and didn’t even think about until recently, that was undoubtedly a criminal act when the story was published, but Donald's response is not to try to explain his mistake to someone in authority but to get away as quickly as possible ("We daren't go back to the highway! Cops will be swarming this way like flies!"). Not the honorable thing to do, obviously, but exactly what many and maybe most people would do in those circumstances. And when Donald is finally persuaded of the stick's powers, he responds not by apologizing to the nephews for his skepticism, but by appropriating the stick for his own uses and shutting the nephews out of his new business.

As I failed to note in my book, and didn’t even think about until recently, that was undoubtedly a criminal act when the story was published, but Donald's response is not to try to explain his mistake to someone in authority but to get away as quickly as possible ("We daren't go back to the highway! Cops will be swarming this way like flies!"). Not the honorable thing to do, obviously, but exactly what many and maybe most people would do in those circumstances. And when Donald is finally persuaded of the stick's powers, he responds not by apologizing to the nephews for his skepticism, but by appropriating the stick for his own uses and shutting the nephews out of his new business.

Would that story, with its unmistakable lapses in the behavior of its principal character, pass muster with today's moral guardians if it were being offered not to adult readers in a hardcover reprint series but to children? I doubt it. But even though there's nothing particularly admirable in anything that Donald does, there's much more substance to him in this story, and in many others by Barks, than there is to any other comic-book character I could name. In a medium that has always been dominated by shallowness and falsity, Donald is that great rarity, a real person.

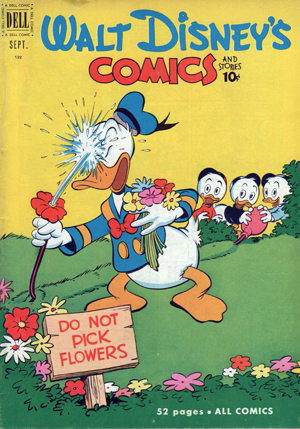

The nephews too are real in Barks’s hands. In the September 1951 Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories, they are Junior Woodchucks, so grimly serious and industrious that they would reduce the Boy Scouts to quivering jelly in any head-to-head contest. The next month they are smug and rebellious hooky players, convinced that school is a waste of their time because they already know everything. Contradictory behavior, perhaps, but no more so than that of many real people—and completely believable as Barks presents it.

What is truly hard to believe is that an artist of Barks’s stature emerged not just in the comic-book industry but from a background that made success in any kind of artistic career unlikely, and that was radically dissimilar to the experiences of most of his comic-book contemporaries.

The people who started working in comic books in the early 1940s, as Barks did, were almost all much younger than he was, and had grown up in big Eastern cities. Barks was born in rural southern Oregon in 1901, on an isolated wheat ranch, and his isolation was intensified by hearing problems that plagued him all of his life. He struggled through a series of physically demanding and low-paying jobs in Oregon and California until he was in his early thirties. It was then that he found steady work in Minneapolis as a cartoonist for the Calgary Eye-Opener, a monthly joke magazine that was smutty by the standards of the time and no more prestigious than the comic books that would appear a few years later.

Barks’s big break came in 1935, when, at the age of thirty-four, he was hired by the Walt Disney Studio as a gag man for the Donald Duck cartoons. Those cartoons were popular but the people who made them were low in the studio’s pecking order. The prestige, the money, and, especially, Walt Disney’s time and attention were all directed toward the new feature cartoons like Snow White and Seven Dwarfs and Pinocchio. So, in 1942, when Barks left the studio to take up life as a poultry farmer near San Jacinto, California, his departure made scarcely a ripple.

He was, however, known as a reliable duck man, and he had already done a little free-lance work for Western Printing & Lithographing, the company that had recently started producing Disney comic books for sale under Dell Publishing’s label. That work included illustrating half of the “Pirate Gold” one-shot. As the need for new material increased with the popularity of comic books, the studio and then the publisher turned to Barks as an obvious resource. He was hired first to draw Donald Duck stories, and then—he had been a Disney writer, after all—to both write and draw the ducks.

He was, however, known as a reliable duck man, and he had already done a little free-lance work for Western Printing & Lithographing, the company that had recently started producing Disney comic books for sale under Dell Publishing’s label. That work included illustrating half of the “Pirate Gold” one-shot. As the need for new material increased with the popularity of comic books, the studio and then the publisher turned to Barks as an obvious resource. He was hired first to draw Donald Duck stories, and then—he had been a Disney writer, after all—to both write and draw the ducks.

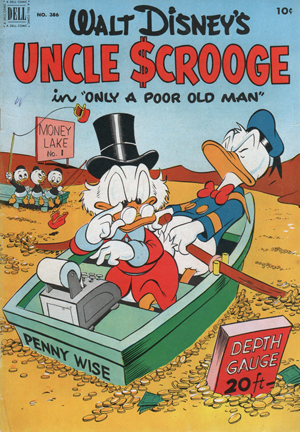

Barks was almost too successful in that role. One of his original characters, Scrooge McDuck, whom he introduced in a Donald Duck one-shot in 1947, graduated to his own title in 1952. Then, in 1953, a quarterly Uncle Scrooge series in effect took the place of the Donald Duck one-shots that had been Barks showcases for ten years. Compared with the Donald one-shots, the Scrooge stories were limited in their inevitable emphasis on Scrooge’s wealth and the adventures the ducks undertook to add to it or protect it.

There was, besides, in the 1950s a more censorious climate than in the 1940s. Comic books of all kinds were under fire, and even so impeccable a publisher as Dell was not immune to the paranoia. Barks had to be more careful, and his stories reflected that new imperative. The best Scrooge stories of the 1950s are wonderful adventure stories for children, but they are not as rich and distinguished as the earlier stories in the Donald one-shots; that is, they offer less to the adult reader. The shorter stories in Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories suffered, too, lacking now the exactness that Barks had displayed in revealing what was going on inside Donald Duck’s mind.

In 1966, Barks retired officially—and eagerly—but his editors were reluctant to let him go, and soon he was drawing storyboard-like scripts for various Dell comic books with the ducks. He received commissions of another sort from fans who wanted oil paintings of the ducks in scenes from his stories. Under licenses from Disney, he painted the ducks over a span roughly as long as his comic-book career, almost until his death in 2000, at the age of ninety-nine.

In some ways Barks’s comic-book career is not over yet, seventy-five years after it began. The reprinting of his stories continues apace, and it is much easier now to read the best of Barks’s stories than it ever has been.

Barks’s achievement was remarkable, duplicated by only a few other authors and cartoonists. He met fully the requirements of a creator of children’s literature, to tell stories that were funny and exciting and whose twists and turns even very young readers could follow, while also providing those readers with stories whose full meanings they could grow into. Lucky have been the children—I was one—who have had Carl Barks as a life’s companion.