COMMENTARY

The Mighty Kelly

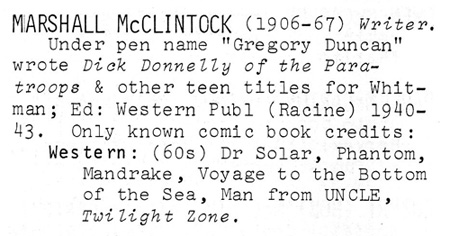

Walt Kelly: The Life and Art of the Creator of Pogo by Thomas Andrae and Carsten Laqua (Hermes Press) is a collection of essays about Kelly and Pogo, mostly by Andrae and Laqua but with contributions by Mark Burstein and Kelly's stepson, Scott Daley. It's not the first book about Kelly and his work, but it's easily the most striking and attractive, thanks to its abundance of beautiful reproductions of Kelly's original artwork (along with some relatively rare published material, comic-book covers in particular). Most of this material originated with Laqua, a Kelly collector in Berlin, Germany.

Walt Kelly: The Life and Art of the Creator of Pogo by Thomas Andrae and Carsten Laqua (Hermes Press) is a collection of essays about Kelly and Pogo, mostly by Andrae and Laqua but with contributions by Mark Burstein and Kelly's stepson, Scott Daley. It's not the first book about Kelly and his work, but it's easily the most striking and attractive, thanks to its abundance of beautiful reproductions of Kelly's original artwork (along with some relatively rare published material, comic-book covers in particular). Most of this material originated with Laqua, a Kelly collector in Berlin, Germany.

Laqua's two essays, on Pogo as a work of art and on the first daily strips from 1948, are illuminating as to the circumstances under which Kelly produced Pogo, and even as to his materials. There's a photo that I find curiously moving, of five of the brushes Kelly used, some of them obviously used very heavily. I have two original Kelly dailies inscribed to me, framed and hanging on a wall a few feet away as I write. After reading Laqua's essay on how Kelly worked, I look at them now with heightened appreciation for their artistry, and heightened affection for the artist.

Kelly, when he was good, was so very good that it's easy to be tempted into overstatement about how good he was, and I think some of the new book's contributors stray in that way, as in Mark Burstein's essay on Kelly's wordplay. But better that kind of overstatement than praise that is too reticent. I find myself tempted to compare Kelly's language when it was in full bloom with Shakespeare's, if only because with both writers the language is so much richer on the page than it can possibly be when spoken. Whether I'm reading Pogo or The Tempest, I want the opportunity to go back and savor what I've just read.

Andrae's essay "Pogo's Politics" is the longest in the book, and as the author has acknowledged, it was written for an academic audience. (As if to warn the general reader, the second paragraph opens with a quotation from the late Michael Rogin, a political science professor at UC Berkeley.) There's a fascinating revelation about how Kelly changed the dialogue in the first Pogo daily he drew for the New York Star in 1948, but there are also many passages of the sort that seem to be mandatory in academic writing. Forbid a professor from referring to "the Other," or some variant thereof, and his or her tongue would undoubtedly cleave to the roof...well, never mind.

Politics first entered Pogo in a highly visible way in May 1953, when Kelly introduced Simple J. Malarkey, his wildcat equivalent of Joe McCarthy, into the strip. I remember how thrilled I was, as a boy Pogo fan, when I realized just who that sinister cat was supposed to be. But as time went by, and Kelly introduced more and more caricatural animals into the strip, my misgivings began to grow. He had started by integrating political comment into everyday life in the swamp, as in the wonderful sequence when Albert is put on trial for supposedly eating the Pup Dog, but as time went by it seemed to me that Kelly increasingly used the caricatures as a crutch: they were supposed to distract us from the woolgathering that filled more and more of Pogo's panels. The caricatures were often very good as caricatures, and they got attention, certainly, even from Russian diplomats (who protested when Nikita Khrushchev was depicted as a pig), but what those caricatural animals actually did was usually not all that interesting.

Re-reading some of those strips now, I'm disappointed again by how Kelly permitted his wonderful characters—Pogo himself, Albert, all the other regulars—to become bystanders, as the caricatures took over. There is, alas, no discussion in Andrae's piece of whether Kelly's increasingly pronounced political content was good for the strip. What we get instead are descriptions of the political context within which Kelly worked, along with explications of the ideas (invariably wise and benign, it seems, as opposed to being occasionally smug and shallow) he advanced through his comic strip. The effect is, I'm afraid, to make the latterday Pogo seem musty, dated, and dull, words that I would hesitate to apply to anything Kelly did before roughly 1960.

Kelly's health undoubtedly accounted for some of the deterioration in his work in the last decade or so of his life. He was enormously productive for several decades, steadily improving as both writer and artist well into the 1950s, when he began to pay the price for what seems to have been a persistent overindulgence in food and, especially, drink. He was only sixty when he died in 1973—an age that seems the more shockingly young to me the older I get—and he had already lost a leg to diabetes, an illness aggravated by his persistent bad habits. As with Walt Disney's smoking, the urge is to step back in time and cry "Halt!" Scott Daley's essay in the new book on Kelly's last years is a bittersweet portrait of a dying man, a Kelly I don't recall encountering in print before.

For all the book's virtues, it also has its problems. There's a lamentable shortage of source notes throughout—not every essay is lacking them, by any means, but sometimes they're missing when they're most wanted, as with unfamiliar and revealing quotations from Kelly himself. The complete absence of notes is particularly frustrating where Andrae's biographical introductory chapter is concerned, because that chapter contains any number of arresting statements (Kelly studied with the famed illustrator Franklin Booth in 1934! Who knew?) that are presumably solidly grounded but whose sources I don't immediately recognize. The chronology as Andrae lays it out, particularly in regard to Kelly's employment in the 1930s, differs from what Kelly was quoted as saying about it, in interviews and in a Disney studio employment history that Andrae himself cites, but reconstructing that chronology with complete accuracy may be impossible.

We hear again in this chapter about how "Kelly was ... inspired by the artistry of his father who painted theatrical scenery and taught his son how to draw." Mark Burstein, in his essay on Kelly's wordplay, enlarges on that datum by describing the senior Kelly as "a theatrical scene painter for minstrel shows and the circus." Walter C. Kelly, Sr., was for many years a foreman at the General Electric plant in Bridgeport, and so any painting of theatrical scenery must have been an avocation that Walt Kelly doesn't mention in his autobiographical essay in the 1962 book Five Boyhoods. He does say of his father that "he was a pretty fair painter," but not in a context that suggests he had theatrical scenery in mind.

It seems sadly inevitable that in beautifully illustrated books like this one, the text will always get short shrift. The biographical essay bears the scars of haste in small but readily avoidable errors, like identifying the creator of the Brownies, Palmer Cox, as "Oliver Cox," crediting Kelly for the third Brownies one-shot (it's by Don Gunn), having Kelly draw "Our Gang" for all fifty-seven of that feature's appearances in Our Gang Comics (George Kerr drew the seventh and ninth installments), and—to be really nitpicky—having him draw the first thirty-five issues of The Adventures of Peter Wheat, instead of the first thirty-three.

Likewise, in a chapter on Kelly at Disney, Andrae has Frank Tashlin leaving the studio after the 1941 strike, whereas Tashlin actually left in March 1941, a couple of months before the strike. Oskar Lebeck's name is misspelled "LeBeck" in that chapter (but correctly in the biographical chapter), and Andrae misdates Pogo's first appearance in Animal Comics to December 1941 (Animal Comics No. 1 was actually published in September 1942).

Andrae repeats without examining closely the claim, originating with Kelly's first wife, Helen, that Walt Disney himself provided Kelly with an introduction to Lebeck, Western Printing's principal comic-book editor in New York, even though the circumstances make that unlikely. When Kelly avoided the strike by returning home to Connecticut to deal with a family crisis—his sister was ill—he clearly intended to return to Burbank as soon as he could. By August, he had apparently changed his mind, as evidenced by his draft board's recording a change of address from Los Angeles to Bridgeport as of August 11, 1941. That was, as it happens, the day Walt Disney left on his famous South American trip. So, if Kelly returned to L.A. to pick up Helen and his belongings around the time his Disney employment ended in September, he couldn't have seen Walt Disney then, because Disney didn't return from the South American trip until October 1941.

Andrae also adopts Helen Kelly's mysterious reference to a "Mike McClutick" at Western Printing. I'm sure she was referring to Marshall "Mike" McClintock, an author and editor of children's fiction in New York. He had no connections with either Disney or Western Printing that I'm aware of, but he did have at least one encounter with Kelly, as described by Mary Reed, who worked for Kelly as a secretary briefly in 1946, on page 22 of the 1985 book Outrageously Pogo, edited by Bill Crouch, Jr., and Selby Daley Kelly.

[A July 5, 2012, update: Thanks to Steve Thompson for sharing some Kelly correspondence with Leo Samuels of Disney's New York office that shows that "Mike McClutick" was indeed Marshall McClintock, and that he was working for Western (in its Whitman Publishing incarnation) in an editorial capacity in August 1941. Walt Disney had written to McClintock recommending Kelly for free-lance work.

McClintock had stronger connections with Western than I realized. Here's the entry for McClintock in the Jerry Bails-Hames Ware Who's Who of American Comic Books (I'm quoting from the 1974 print edition; there's also an online version that I don't think is quite as helpful in this case):

There's no mention of Oskar Lebeck in the Kelly-Samuels correspondence, but it certainly seems possible that Walt Disney wrote to both McClintock (as an editor of children's books) and Lebeck (as an editor of comic books) on Kelly's behalf. Stay tuned!]

Elsewhere in the Andrae-Laqua volume, Heywood Broun is renamed "Hayward," the movie title Ninotchka comes out as Ninoshka, Elia Kazan metamorphoses into Kazin (Alfred, presumably) in an endnote, Kay Kamen becomes Kaymen, and so on. There are oddities: in the political essay. Andrae relies on R. C. Harvey as his authority when he correctly identifies an "Our Gang" character, Professor Hector Hannibal Horatio Gravy, as a precursor of Pogo's P. T. Bridgeport; but why not refer to the comic-book story itself? The professor first appears in Our Gang Comics No. 17, and even if that comic book was not at hand, the story has been reprinted as part of Fantagraphics' incomplete series of Kelly's "Our Gang" stories.

Fortunately, however troublesome the errors and oddities, there's the compensation not just of the wonderful illustrations, but also the interview with Ward Kimball, conducted by Andrae and Geoffrey Blum, about Kelly's days at Disney. This interview has been published before, in the out-of-print book Phi Beta Pogo, and it's good to have it available again, with generally superior (and certainly better reproduced) illustrations. But here's another problem: the interview as originally published is incomplete in the new book. Most damaging, the three letters from Kelly to Kimball included on pages 142-43 of Phi Beta Pogo are missing. I haven't made a line-by-line comparison to see what else has been cut, but there's a question-and-answer missing from page 140 (about Kelly's departure from the Disney studio), and another from page 137-38 (about Kelly's drinking). But there's also new material (about Walt Disney's sense of humor) on page 61! All very peculiar.

[Posted June 25, 2012; updated July 5, 2012]