COMMENTARY

SpongeBath

I saw The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie early one recent afternoon, at a private screening. It wasn't supposed to be a private screening, mind you, it just worked out that way. I was the only person in the theater.

After

the movie, my head was buzzing with questions—questions inspired

by the previews, as it happens, rather than by the feature. Why

will Pooh's Heffalump Movie, a new Disney excrescence, be

showing, as a title card puts it, "only in theatres"

(emphasis supplied)? Why not "only in theaters"?

Is this some subtle appeal to snobbery? Are we supposed to connect

that vaguely British spelling with Winnie the Pooh's upper-crust

origins?

After

the movie, my head was buzzing with questions—questions inspired

by the previews, as it happens, rather than by the feature. Why

will Pooh's Heffalump Movie, a new Disney excrescence, be

showing, as a title card puts it, "only in theatres"

(emphasis supplied)? Why not "only in theaters"?

Is this some subtle appeal to snobbery? Are we supposed to connect

that vaguely British spelling with Winnie the Pooh's upper-crust

origins?

The most important such question: why would anyone whose brain has not been surgically removed and replaced with mashed potatoes consider for a second going to see the film called Racing Stripes? To judge from the preview, it's a disgusting Babe-like concoction about a zebra that becomes a race horse, in which real animals with computer-manipulated mouths speak with the voices of movie stars. Has the world been waiting to hear Dustin Hoffman as the voice of some animal?

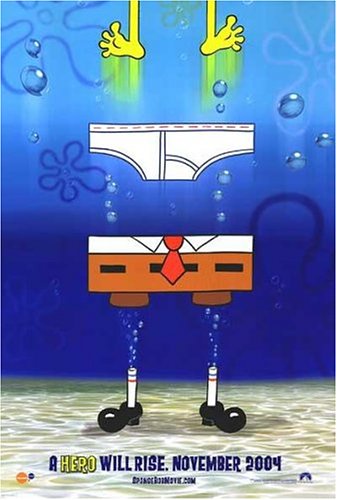

Oh, yes, The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie. I thought it went straight downhill, as well as underwater, after the funny opening business with live-action pirates. It's an honest-to-goodness television cartoon, folks, just on a bigger screen, and that means, ipso facto, it almost certainly could never amount to much.

I say that not out of snobbery where TV in general is concerned, but from the belief that TV is a rigorous medium in its way. After almost sixty years of the medium's existence as a vehicle for popular entertainment, I think it's clear that it's possible to do only a few things really well for television. Sports is one; situation comedy is another. A Seinfeld movie would be a ridiculous idea—I don't think anyone has ever seriously suggested one—but a self-contained Seinfeld half hour could be heavenly, and often was.

On the other hand, I can't think of a TV western that was ever much good, compared with the best big-screen specimens, and the same is true of TV animation, even the best of it, like The Simpsons. (Turn the sound off during a Simpsons episode and there's not much to laugh at.) Jay Ward, early Hanna-Barbera, all the things usually cited as exceptional TV cartoons—they really weren't all that good to begin with, except by comparison with the even worse stuff surrounding them, and they haven't held up. I watched those cartoons when they were new, and I liked them a lot, but watching Rocky and His Friends or Huckleberry Hound now is painful. I have higher hopes for The Simpsons' durability, but not much higher.

Ultimately, it all comes back to the animation. There is a threshold below which a character's movement is so conspicuously mechanical—so obviously the product of some industrial process, rather than movement initiated by the character itself—that interest in the character as character is unavoidably defeated. Interest has to light elsewhere, on the dialogue particularly. Unless its author is someone like Oscar Wilde, though, witty dialogue depends heavily on its cultural context, and so it tends to go bad about as quickly as fresh milk. Michael Maltese was a great cartoon writer, but you can't tell it from his Hanna-Barbera work; his dialogue is much funnier at Warner Bros., where Chuck Jones's drawings are doing the heaviest lifting.

Television animation, like stop-motion animation and computer animation, suffers from a partial paralysis that even someone as gifted as Brad Bird can finesse but not quite defeat. That paralysis has different origins; in TV animation it has always originated in tight budgets and the resulting need to conserve drawings, whereas in stop-motion and computer animation it's the byproduct of manipulating solid forms that by their nature can't admit of much flexibility. (How can a computer-animated character go off-model for expressive purposes, even very briefly, after perhaps a year of effort has gone into determining what on-model means? Being on-model is the very essence of a computer-animated character's existence.) But such limitations on freedom of movement—limitations that originate externally, rather than in an artist's decisions—are always debilitating, wherever they come from.

If you've seen the Disneyland TV show called "An Adventure in Art," you'll recall that Walt Disney emphasizes the role played in the life of the Disney studio by Robert Henri's 1923 book called The Art Spirit—-really a sort of commonplace book, patched together from Henri's lectures and speeches. I can't recall seeing references to the book in any of the thousands of Disney documents I've read, but no doubt there are some; and certainly the book has echoes in the studio's practices in the thirties and forties. Henri speaks of brush strokes, for example, in terms that evoke the best drawn animation: "Strokes which move in unison, rhythms, continuities throughout the work; that interplay, that slightly or fully complement each other."

Like most TV cartoons these days, The SpongeBob SquarePants

Movie was animated in one or more of the Asian cartoon factories.

I can recall only one moment in the film when I sensed the life-giving

flow of the drawn line in the animation of the characters (it happens

when one huge fish is devouring another). Most of the artwork has

a kitschy brightness I associate with the Hanna-Barbera output of

the seventies. As for the writing, there is in it scarcely even

the pretense of wittiness as it's usually conceived. What there

is instead, as in the TV show, is silliness, aggressively and in

abundance—and that's OK, in principle. If a silly movie provides

a few great belly laughs, it justifies its existence, no matter

how dumb most of it is; I remember Airplane with a smile,

for just that reason. Perhaps other people found those belly laughs

in The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie (and perhaps seeing it

in an empty theater wasn't fair to the film), but I could muster

only an occasional smile.

The one striking thing about SpongeBob SquarePants, movie

and TV show, is how thoroughly its creator, Stephen Hillenburg,

has absorbed the influence of John Kricfalusi's original Ren

& Stimpy, to my mind one of the very few TV cartoons that

demands serious attention. The Kricfalusi influence shows up in

drawings that are sometimes physically extreme—bulging eyeballs,

scraggly teeth—compared with the characters' usual appearance.

(The movie has its fart and bathroom gags, too, but those are so

ubiquitous now in children's films that it's hard to give John K.

much credit or blame for them.)

With Kricfalusi, though, there was no "usual appearance" for his characters, and his drawings always seemed to be straining at the leash. Watching Ren & Stimpy was as scary and exciting as being trapped in an elevator with someone suffering from a particularly severe case of Tourette's syndrome—there was always the sense that some sickening obscene outburst lay just ahead. (In his newest R&S cartoons, the outbursts have come, and they're just as sickening—and depressing—as I might have feared.) There's no mistaking Stephen Hillenburg for a mental case, though; he's just a nice boy who's havin' fun talkin' a little dirty.

I've never been quite clear on why SpongeBob was a favorite in the gay community, but maybe I've finally figured it out. The glimpse of SpongeBob's yellow butt is a false clue, I think, as is even the scene in which SpongeBob's starfish friend Patrick carries a SpongeBob banner clenched in his buttocks. Rather, SpongeBob and Patrick seem to be analogues for those unattractive, clueless fanboys who always manage to find one another, usually at a comic-book store or a comics convention. You can all too easily imagine how these two almost-sexless characters could accidentally start playing with each other's privates and eventually turn into flaming queens—all by mistake! Guys, guys, you're really straight!

That's sort of funny, I suppose. But I sure was glad to see the pirates come back, after the end credits. If those clowns turn up in a movie of their own, I'll buy a ticket. But only if there's no preview of Racing Stripes on the program. Once is enough.

[Posted December 11, 2004]