COMMENTARY

The Prison of Genres

I still have a little glossary of literary terms I bought when I was a freshman at Northwestern, and it defines "genre" as a "word imported from France to signify a literary species or, as we now often say, a literary 'form.' … At present genres are most frequently held to be convenient but rather arbitrary ways to classify literary works."

However

accurate that definition may have been when the glossary was first

published, more than sixty years ago, it seems to me inapplicable

to what many people would now call "genres" of film or

popular fiction. Westerns, horror, crime, science fiction—all

those familiar categories invite the "genre" label in

a way that mainstream books and films do not. If a book or film

plainly belongs to a genre, it usually has a faintly disreputable

air; it is presumed to be dependent on formulas and conventions

in a way that more serious works are not.

However

accurate that definition may have been when the glossary was first

published, more than sixty years ago, it seems to me inapplicable

to what many people would now call "genres" of film or

popular fiction. Westerns, horror, crime, science fiction—all

those familiar categories invite the "genre" label in

a way that mainstream books and films do not. If a book or film

plainly belongs to a genre, it usually has a faintly disreputable

air; it is presumed to be dependent on formulas and conventions

in a way that more serious works are not.

American comic books of the traditional kind have been unique among

this country's art forms in that almost all of them have belonged

to one clearly defined genre or another. Successful comic books

that fall outside existing genres tend to establish new genres,

almost instantaneously. That was most famously true of the superheroes

that multiplied so rapidly after Superman laid down rules in Action

Comics No. 1, but the pattern was repeated with crime and horror

comic books after World War II, and with comic books of other kinds

as well. On the rare occasions when publishers tried to escape the

genre trap—most famously in the mid-fifties with EC's New Directions

line—their efforts failed, quickly and decisively.

Great cartoonists like Carl Barks and Will Eisner have been able to work successfully within genre conventions, at least for a time, but those conventions have always asserted their power even when they were being ridiculed. Harvey Kurtzman savaged one comic-book genre after another in EC's Mad, but such mockery quickly mutated into a genre of its own, as the newsstands filled with copycat titles that included EC's own Panic.

In many genres, the best comic books have not been the most popular—in the teenage genre, the little-known fifties Dell title Henry Aldrich, written by John Stanley, was vastly superior to the much more popular Archie titles—and some genres have resisted producing any material of value. Many students of the comics would single out the romance titles, which first appeared in the late forties, as the prime example. Even more than the teenage comics, which also appealed to a largely female audience, such comic books pandered to their readers, stoking their self-pity and insecurity. There's not much room for artistry when a comic book's mission is defined in such degraded terms.

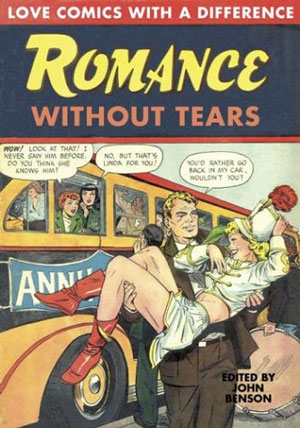

In Romance Without Tears (Fantagraphics, $22.95), a trade-paper anthology of nineteen stories chosen from the romance comics published in the late forties and early fifties by the St. John company, the esteemed comic-book scholar John Benson attempts to rescue Dana Dutch, the presumptive writer of those stories, from the justifiable oblivion to which almost all the writers and artists for romance comics have heretofore been consigned.

There are wonderful things about Benson's book. It's a splendid example of how such comic-book stories should be presented, with color reproduction that excels anything else I've seen in a book of this kind (how I wish my own Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics had been printed this well!). The gallery of covers is wonderfully evocative, summoning up those dear dead days when newsstands were full of hundreds of intriguing and outrageous comic books.

But after reading the stories themselves, and the introduction in which Benson lays out his case for them, the best I can offer as a verdict is "not proven." There is nothing at all real about the way the characters in Dutch's stories look or speak. Many of them are supposed to be high school students, but they're drawn, mostly by Matt Baker, to look ten years older (in keeping with the pander principle). The dialogue, especially the self-absorbed first-person narration that hovers over many of the panels, is stilted. And because these alleged teenagers are usually preoccupied with microscopic questions—as exemplified by stories with titles like "I Tried to Buy Love—With Kisses"—the total effect is claustrophobic.

It's no doubt true, as Benson writes, that Dutch's heroines are more self-possessed than the helpless ninnies common in other romance comics, and that they learn from their experiences and go on with their lives in ways that are not typical of stories in the genre. But I think those virtues can assume importance in a reader's eyes, at least on the scale that Benson assigns to them, only if the reader knows the really bad romance comic books, the ones Dutch didn't write, as well as Benson does. That is knowledge that most readers will choose not to acquire.

The root problem with many of Dutch's stories in Romance Without Tears, and with romance comics in general, is that they ignore or minimize the overwhelmingly important role of sex. Just a few of the stories in Benson's book are driven openly by the confluence of male and female desire (as opposed to the man's trying to trick the girl into bed, as happens in "Tourist Cabin Escapade"), and it was only while reading one such story, "Masquerade Marriage," the last and best story in Romance Without Tears, that I found myself wondering what was going to happen next. Benson's gallery of comic-book covers is especially revealing in this regard—most of them promise more than what the corresponding stories deliver, and what they promise is titillating sexual content.

When the St. John stories were published, roughly twenty years before the advent of the pill and the "sexual revolution," sex was not just exciting but dangerous. Things weren't that different when I was in high school a decade later—I remember the whispers about furtive back-seat couplings and girls "in trouble" and shotgun marriages. (Now, in the wake of the AIDS epidemic, sex has become a little frightening again—probably not a bad thing.) Any comic-book publisher dealing with such volatile material would necessarily approach it carefully, but subtlety has never been comic books' long suit, and it was easier to pretend sex didn't exist than to find acceptable ways to introduce it, as Dutch did in "Masquerade Marriage."

If I'm forced to read stories from romance comics, I'd rather they be like those in Real Love (Eclipse, out of print), a 1990 collection of late-forties stories by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, reproduced in gritty black and white rather than color. (Richard Howell, in his introduction, makes a convincing case for S&K as the inventors of the genre.) In the S&K stories, the characters are older and the situations more interesting, with sex subsumed, as it is in real life, in a matrix that is also made up of such things as money, power, and sibling rivalry. Sometimes, in contrast to the St. John stories, men are the narrators; and since Kirby was involved, the energy level is much, much higher than in the Matt Baker-illustrated stories.

That's not to say that the Simon and Kirby stories aren't pretty terrible—the first-person, confessional captions that were de rigueur in romance comics are just as deadly as the somber, superfluous captions in Al Feldstein's EC science-fiction stories—but at least they kept me awake. I wish I could say the same about Dana Dutch's stories in Romance Without Tears.

[Posted April 7, 2004]