COMMENTARY

Reading the Mouse

Years ago, in a choleric L.A. Weekly review of my book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, Charles Solomon took me to task for, among many other things, failing "to explain what made Felix the Cat so popular with audiences all over the world during the '20s, or why Mickey Mouse became even more popular during the '30s."

Years ago, in a choleric L.A. Weekly review of my book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age, Charles Solomon took me to task for, among many other things, failing "to explain what made Felix the Cat so popular with audiences all over the world during the '20s, or why Mickey Mouse became even more popular during the '30s."

I'm not sure how one goes about "explaining" such popularity, any more than one can "explain" the more recent popularity of, say, Justin Bieber. Probably the best one can do is take note of the phenomenon and offer some hypotheses, unless one is a tenure-crazed academic (or petulant newspaper reviewer) who routinely offers speculation as fact. The task is particularly difficult where Mickey Mouse is concerned because that character was in the days of his greatest popularity little more than a cipher, barely a character at all.

My best guess is that the Disney cartoons benefited most in their early days not from anything distinctive about Mickey Mouse—his predecessors Felix and Ko-Ko the clown were both more interesting, as characters, than Mickey—but from Walt Disney's success at melding sound and images in his cartoons. Watch some of the earliest competing sound cartoons, like Lantz's or Van Beuren's, and the superiority of the Disney cartoons is immediately apparent. They hang together as the other cartoons do not, and they employ both sound effects and music more inventively than other films of any kind, thanks to the tight synchronization made possible through Disney's bar sheets and click tracks.

Walt was a year or two ahead of all of his competitors. Only Harman and Ising, who copied the Disney methods when they began making Looney Tunes in 1930, came at all close to matching his cartoons' integration of all their elements. Mickey Mouse, as the lead character in the Disney cartoons, attracted interest and enthusiasm that might have been directed more to Disney himself if the nature of his accomplishments had been better understood. Walt certainly knew what was going on—thus his remark in 1956 that the "main thing" about Three Little Pigs (1933), a much more sophisticated cartoon than his early Mickeys, “was a certain recognition from the industry and the public that these things could be more than just a mouse hopping around.”

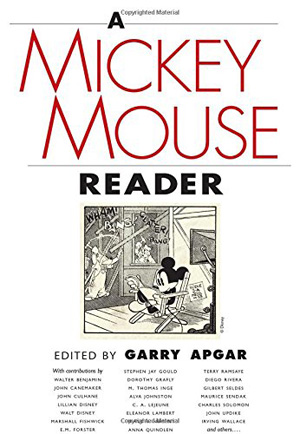

With the early Disney sound cartoons a great success but Mickey Mouse himself not much more than a blank slate, the way was open eight decades ago for American and European writers to find in Mickey significance of many kinds. Their successors over the years have continued to do so. The most thoughtful ruminations about Mickey make up the heart of A Mickey Mouse Reader (University Press of Mississippi), an excellent new book edited by the art historian Garry Apgar.

To quote from my blurb on the jacket's back cover, "A Mickey Mouse Reader is a book that commands attention for many reasons, but not least because it is a continually surprising pleasure to read. There is in the book much that is worth reading for its own sake, and not just as a record of how critical and public sentiment have changed in the more than three-quarters of a century since Mickey’s debut. Apgar’s own commentary gives the book a reassuring 'spine' of informed judgment; that is, his authorial persona—especially his sophistication as a scholar in the visual arts—encourages the reader to accept his choices of what to include in the book. He has taken seriously the job of choosing the contents and as a result has come up with many fascinating items, including some originally published in other languages, that a less industrious compiler would have missed."

All very true, if I do say so myself. A Mickey Mouse Reader traces the arc of Mickey's career, from brief trade-paper notices and reviews in the late twenties, through serious and semi-serious essays by the likes of Gilbert Seldes and E. M. Forster in the thirties, on to his emergence as the ultimate corporate icon in the fifties and sixties. It concludes with a potpourri of more recent pieces written by people, most notably the late John Updike, who have known Mickey not as a novelty—after all, his debut took place eighty-six years ago next month—but as a constant presence.

There's a cluster of items that appeared at the time of Mickey's fiftieth anniversary, in 1978, including one by Maurice Sendak that was first published in TV Guide. It's a bit of a shame that Apgar couldn't reproduce the Sendak drawing that accompanied that essay, of Sendak himself in front of a full-length mirror with Mickey as his reflection. Some variation on that image, with the people who were writing about Mickey seeing themselves in him, or vice versa, could have accompanied many of the pieces in the book.

I don't think anyone who has not gone through the ordeal of clearing the use of copyrighted material can appreciate just how much Apgar has accomplished by not only locating but also getting permission to reproduce important items that would be all but impossible to find and read otherwise. Many of those items would be in the public domain if our copyright laws had not been hopelessly distorted—at the behest of the Walt Disney Company, above all—by the amendments Congress has passed since 1976. That the book is, besides, a handsomely designed, admirably solid object—a real book, when such things are under siege—is one more reason to applaud, and to buy. A Mickey Mouse Reader is reasonably priced, too, especially for a hardcover.

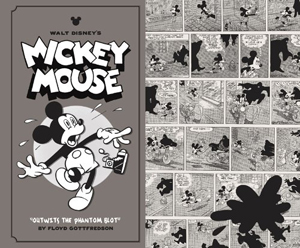

Floyd Gottfredson's name turns up only twice in the Reader's index, for single references in essays by M. Thomas Inge and Apgar himself, and I noticed just a few references, in passing, to the Mickey Mouse comic strip that Gottfredson produced (with help) for more than forty years. That may seem a little odd, because it was in the comic strip that Mickey became a more distinct character, as a pint-size adventure hero and free-lance detective, than he ever was in the animated shorts, even when those shorts cast him in similar roles. Mickey retained his detective identity in the Disney comic books even after the comic strip became a bland gag-a-day production, with Mickey the blandest single element. The earlier Mickey, the little adventure hero, is being celebrated in an ongoing series of reprints by Fantagraphics Books, the latest being the fifth volume of the daily comic strip (there is a separate series made up of the color Sunday pages). Mickey Mouse Outwits the Phantom Blot, edited by David Gerstein and Gary Groth, consists of daily strips from 1938-40.

Floyd Gottfredson's name turns up only twice in the Reader's index, for single references in essays by M. Thomas Inge and Apgar himself, and I noticed just a few references, in passing, to the Mickey Mouse comic strip that Gottfredson produced (with help) for more than forty years. That may seem a little odd, because it was in the comic strip that Mickey became a more distinct character, as a pint-size adventure hero and free-lance detective, than he ever was in the animated shorts, even when those shorts cast him in similar roles. Mickey retained his detective identity in the Disney comic books even after the comic strip became a bland gag-a-day production, with Mickey the blandest single element. The earlier Mickey, the little adventure hero, is being celebrated in an ongoing series of reprints by Fantagraphics Books, the latest being the fifth volume of the daily comic strip (there is a separate series made up of the color Sunday pages). Mickey Mouse Outwits the Phantom Blot, edited by David Gerstein and Gary Groth, consists of daily strips from 1938-40.

The title sequence, which ran for four months in 1939, is probably the most famous, and arguably the best, of Mickey's comic-strip adventures; it was reprinted and sometimes redrawn for any number of Disney comic books over the years, first in the earliest Dell Mickey Mouse one-shot and then as a serial in six 1949 issues of Walt Disney's Comics & Stories. That serial, as redrawn by Dick Moores (and, for one issue, Bill Wright), is among my earliest comic-book memories, and I've always been very fond of it. It's exciting stuff, with Mickey's life in real danger several times.

Many of the other adventures in the book are not as good, and a pairing of Mickey with Robinson Crusoe is simply embarrassing (as one of the book's annotators forthrightly acknowledges). Mickey lost his pie-cut eyes in the Crusoe strips, having to make do ever after with much more ordinary irises and pupils. And then there's the strange and decidedly uncharacteristic fantasy episode in which Mickey follows a genie, the kind that emerges from a lamp, to "Genieland" and tries unsuccessfully to impose happiness on its miserable inhabitants, in a thinly veiled attack on the New Deal. Gottfredson is always worth reading, even at less than his best, but there is a persistent awkwardness in the episodes in the new book—the dialogue balloons often seem to have been shoehorned into the panels—that is disappointing.

More so than the comic-book story, the daily comic strip is confining as a narrative medium, with its demand that each day's three- or four-panel installment in a continuing story make some sort of sense on its own. And then there's the work involved in writing and drawing those daily panels. Add in a Sunday page—more panels to play with, but also more to write and draw—and it's no wonder that it was common for a leading newspaper cartoonist, like Gottfredson, to operate as the senior member of a team. Seeing Gottfredson wrestle with his comic strip's demands made me all the more appreciative of the genius of a few cartoonists like Elzie Segar and Walt Kelly, who seemed completely at ease as comic-strip creators—working with assistants, to be sure, but never letting Thimble Theatre or Pogo resemble a factory product until ill health pulled them down.

What would Gottfredson have been like as a comic-book cartoonist, I wonder? So many of his Mickey Mouse episodes work very well as comic-book stories, when they've been adapted for that medium, that it's tempting to believe that original Gottfredson comic books would have been as successful as Carl Barks's comic books with Donald Duck. But maybe not. Donald was always a distinctly comic character, as Mickey was not; there were many facets to the personality of Barks's Donald, but none of the vagueness that turned out to be so useful to the authors of many of the essays in A Mickey Mouse Reader. A Donald Duck Reader could include some keen stuff, like James Thurber's very funny "The Breaking Up of the Winships," but the pickings would be much leaner than those for the Mickey Reader.

What would Gottfredson have been like as a comic-book cartoonist, I wonder? So many of his Mickey Mouse episodes work very well as comic-book stories, when they've been adapted for that medium, that it's tempting to believe that original Gottfredson comic books would have been as successful as Carl Barks's comic books with Donald Duck. But maybe not. Donald was always a distinctly comic character, as Mickey was not; there were many facets to the personality of Barks's Donald, but none of the vagueness that turned out to be so useful to the authors of many of the essays in A Mickey Mouse Reader. A Donald Duck Reader could include some keen stuff, like James Thurber's very funny "The Breaking Up of the Winships," but the pickings would be much leaner than those for the Mickey Reader.

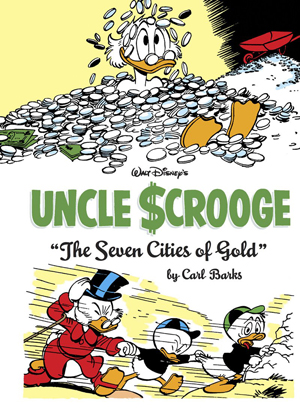

Better, I think, to pick up one of Fantagraphics' Barks volumes—from the series reprinting Donald Duck stories, or the companion series reprinting Uncle Scrooge stories, both edited by Groth and J. Michael Catron—and marvel at the work of a cartoonist who was as much at home with the comic-book story as Walt Kelly was with the daily comic strip. The latest book and second Uncle Scrooge volume, The Seven Cities of Gold, suffers from the shortcomings of earlier Fantagraphics volumes—again, the commentaries have been parceled out among too many commenters, contributing to a can-you-top-this atmosphere in which some contributors strain to find something worth saying about stories or even gag pages that don't repay the attention. But the stories (all from Uncle Scrooge issues of 1954-56) look very good, and they're all very much worth reading, even when they're not among Barks's best.

For his best, you should turn to any of the volumes released so far in the Donald Duck series, the latest of which, Trail of the Unicorn, embraces stories from Walt Disney's Comics & Stories and Donald Duck that were published in 1949 and 1950. When Barks was at his very best, as he was in those years, there was never a cartoonist any better.

[Posted October 29, 2014]