COMMENTARY

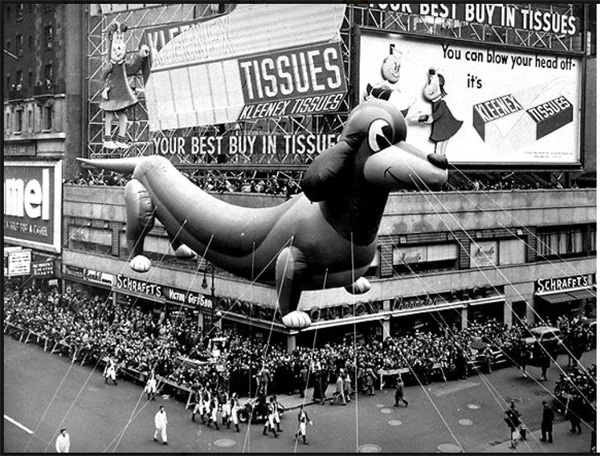

| Little Lulu in the 1940s was not only a comic-book and animated-cartoon star (in a Paramount series), but was perhaps best known as the cartoon spokesgirl for Kleenex tissues, as seen in this billboard during a Macy's Thanksgiving parade. Thanks to Milt Gray for sharing this photo and the one at the end of this piece. |

The Mysterious Mr. Stanley

As Bill Schelly notes in his new biography, John Stanley: Giving Life to Little Lulu (Fantagraphics), I was the first to identify Stanley as the creative genius behind the Little Lulu comic books, back in the 1960s, when I discovered that the U.S. government's Catalog of Copyright Entries credited Stanley as the author of the Lulu issues in Dell's Four Color series. I don't remember for sure how I got his address, but it was probably from an executive at Western Printing & Lithographing, which had produced the comic books for Dell. It then took me a couple of years to work up the nerve to write to him. I finally did write to Stanley in 1967, sending him a copy of the sixth issue (mimeographed) of my fan magazine Funnyworld. I heard nothing for weeks, and a second letter produced no response, either, so I gave up on Stanley, for a time.

Maggie Thompson—who has always been braver than me—telephoned Stanley a few years later, and she wrote a piece based on their conversation for the sixteenth issue of Funnyworld (by then a professionally printed magazine); it was titled "The Almost-Anonymous Mr. Stanley." I sent Stanley a copy of that issue, after I published it early in 1975, and again I got no reply. There may have been something at work other than rudeness. Both of those issues of Funnyworld had covers devoted to Carl Barks, and No. 16 was a "special Carl Barks issue" with the single page of Maggie Thompson's piece on Stanley tucked away deep in the magazine, behind several Barks articles. So, I was trying to attract Stanley's interest with issues of my magazine devoted not to his work but to another cartoonist who worked for the same publisher. Not too smooth.

If my initial attempts to get in touch with Stanley annoyed him, that should not have been the case in 1982, when I sent him a copy of A Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics, which I co-edited with Martin Williams. That book included four Stanley stories, with full credit to his authorship. A panel from one story shared the front of the dust jacket with panels from stories by Will Eisner, Walt Kelly, and Siegel and Schuster. Not exactly shabby company, but again I heard nothing.

In the meantime, Stanley had made one appearance at a comics convention, the 1976 Newcon in Boston, an event I have often regretted missing. (I was in California then, suffering from the delusion that I was completing the research for my history of Hollywood animation. I was off by only a little more than twenty years.) If it were not for what Stanley told Newcon's organizer, Don Phelps, and Newcon audiences, and what he told Maggie Thompson in their telephone interview, we might know little more about Stanley and his comic-book career than we know about, say, Dan Gormley, a Western Printing stalwart whose life is a blank except for a photo or two and some scrappy credits. Stanley could have been a starring guest at other comics conventions, if he had wished, but he recoiled from such opportunities.

Stanley may have thought he was too good for the comic books of the 1940s and 1950s—and thus for the adult fans who loved those comic books as children—and he may have been right. He was, on the evidence of what some of his former colleagues said about him, and the cool, dry tone of his best Little Lulu stories, more sophisticated and intelligent than his typical comic-book contemporary. If, as his colleague Dan Noonan said, his taste in reading ran to the likes of Samuel Pepys's diaries, that would have set him apart from almost everyone else working in comics then.

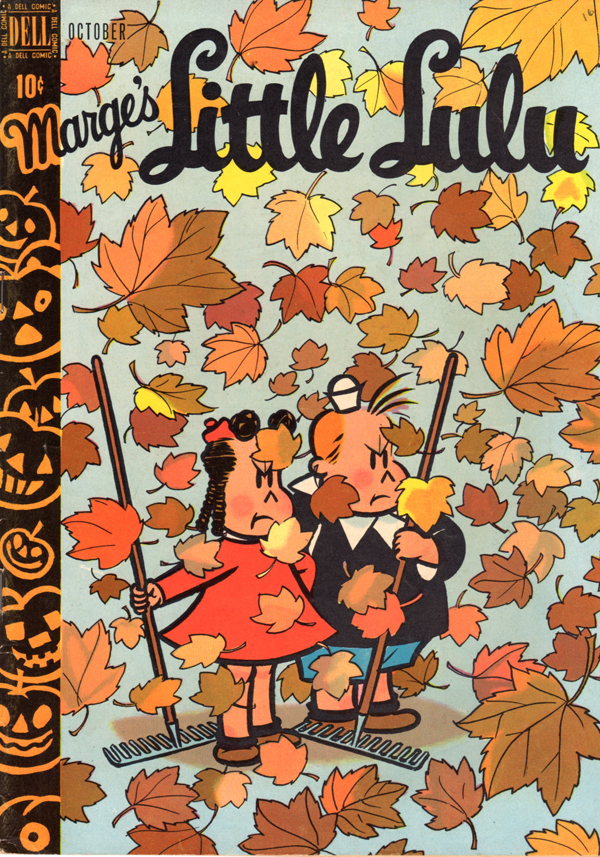

In the memories of Noonan and Morris Gollub, another colleague, Stanley was a better fit for the New Yorker than for comic books. He did in fact sell one cartoon to that magazine, or, more precisely, he sold an eight-part cartoon that is not far removed from some of his gag pages for Little Lulu: low-key, building to a quiet conclusion rather than a boffo climax. So natural does the fit feel, of Stanley and the magazine—even his Little Lulu cover drawings from around 1949 look like miniature New Yorker covers—that it's tempting to believe that Stanley must have done more work for the New Yorker, selling gag ideas that other cartoonists drew. Both Noonan and Gollub thought he did, and Schelly writes as if he must have, even though there is no evidence of that. According to Schelly, in an online interview with The Comics Journal, Frank Young, the most dedicated of the Stanley researchers, reviewed all the New Yorker cartoons from 1946 to 1955 and found none that matched the rough sketches for such cartoons in Stanley's files.

| One of Stanley's New Yorker-flavored Little Lulu covers, this one from the October 1949 issue. |

"We were never able to figure out how to dig deeper," Schelly said in the interview. "Unfortunately, [John Stanley's son] Jim Stanley didn’t have any pay vouchers among his father’s papers. Maybe somewhere in the bowels of the magazine’s archives, answers could be found among the thousands of gag cartoon submissions."

In fact, answers are readily accessible, as signaled by an endnote in my book Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books. The New Yorker's archives are held by the New York Public Library, and the inventory for that collection—which includes the papers of James Geraghty, the magazine's art editor from 1939 to 1973, when Stanley might have been submitting gag ideas—includes no references to Stanley. When I wrote to the library about the possibility of Stanley's having sold more to the magazine than that one multi-part cartoon, I heard from Lee Spilberg of the Manuscripts and Archives Division:

I have checked the Geraghty papers, and there is no correspondence with Stanley there. I also checked the folders in Series 7 of the New Yorker records [Art Works: Run and Killed, 1944-1980], and there is nothing from or about Stanley. However, there is a piece of "negative" information that may or may not be useful. On a complete list of "killed" artwork from 1945-1949, Stanley does not appear, implying that Stanley never went through that particular experience.

In other words, Geraghty did not buy any ideas from Stanley that were ultimately not used. He did buy that one cartoon, of course, and there survived in Stanley's papers a note from Geraghty, dated only November 14, no year, rejecting some gag ideas that Stanley had submitted (Jim Stanley sent me a copy of that note). But that's it.

I spent days at the NYPL when I was writing Funnybooks, chasing down scraps of information about the Dell comic books, but I didn't visit the Manuscripts and Archives Division; Lee Spilberg's reply seemed sufficiently thorough to make a visit superfluous. But maybe not. Noonan's and Gollub's memories of Stanley's New Yorker associations are specific enough to give me pause. Did they inflate what Stanley told them, or (and this seems more likely) did Stanley himself do the inflating? He had sold a cartoon to The New Yorker, he had passed through the heavenly portals; how painful it would have been to tell his friends that his triumph, the sort of triumph they could only dream of, was a fluke.

If Schelly had asked for my opinion, I would have raised such questions; but although he asked for copies of a lot of documents, he didn't ask me to review his manuscript. His book fails to acknowledge the possibility that Stanley, a proud, fiercely intelligent man, lied to his friends rather than admit that he had suffered the humiliation of rejection by the magazine that seemed like the perfect fit for his talents

If Schelly had asked for my opinion, I would have raised such questions; but although he asked for copies of a lot of documents, he didn't ask me to review his manuscript. His book fails to acknowledge the possibility that Stanley, a proud, fiercely intelligent man, lied to his friends rather than admit that he had suffered the humiliation of rejection by the magazine that seemed like the perfect fit for his talents

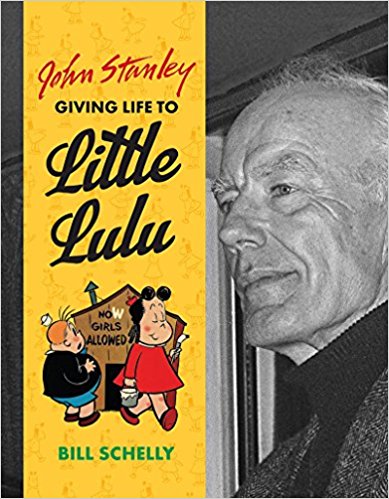

The great virtue of Schelly's book is that, thanks in large part to Jim Stanley, he tells us more about Stanley's family history and the last few decades of his life than we've known before, and shows us family photos that probably no one outside the family has ever seen. But what makes Stanley interesting, to me and others, is not the Irish Catholic heritage he shared with so many other people, but his work as a cartoonist and a comic-book writer over a roughly twenty-year span from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s. The critical question is how well the book illuminates that part of his life.

Schelly (who lives in Seattle) did no research on the East Coast, which he told me he could not afford. His citations of documents from the Marge Collection at Harvard, the most important resource for a Stanley scholar apart from the comic books themselves, are to documents I provided; likewise, he quotes more extensively from my Morris Gollub transcript, which I copied for him, than I did myself in Funnybooks. I say this not to be peevish. I spent a lot of money, for travel especially, while I was accumulating such material, and I wouldn't have made the copies for Schelly if I didn't think he would make good use of them. But a book of this kind, if it is to do its job, has got to persuade us of its subject's merits through both the weight of its evidence and the force of its arguments, and I don't think Schelly's John Stanley fully meets that test. It's wonderful to have those Stanley family photos in print, but if someone is not already convinced of Stanley's great worth as an artist, they may find them mere curiosities.

My recollection is that the book as announced would have included some of Stanley's best stories, in complete form, and it's a pity that it's simply an illustrated biography (a "coffee-table book" about "one of the most influential 'girl power' comic book writer/artists," to quote Fantagraphics' embarrassing description) with pages and panels from published stories in overstated color. Perhaps the problem was copyrights, which, as I learned in work on Funnybooks, are a frustrating tangle where not just Little Lulu but also many other comic-book properties are concerned.

Copyrights aside, a larger problem is that Stanley's stories hold up better when they are read, so to speak, in bulk. Having to zero in on a few stories can mean, as a practical matter, limiting the plausible choices severely (this is not a problem that arises with Carl Barks). When I was recruited to help choose stories from the Dell comic books for the Art Spiegelman-Françoise Mouly anthology The Toon Treasury of Classic Children's Comics, it was a given that Stanley would be represented, and the original thought was that "Five Little Babies" (from the August 1951 Little Lulu) would not be chosen because it had already appeared in my Smithsonian anthology; but as we weeded out one candidate after another, we eventually concluded that there was no escaping "Five Little Babies." It was just too good. Too many other Stanley stories were, despite their virtues, flawed by comparison, as if they'd been tossed off by a brilliant storyteller who was contemptuous of the demands of the form in which he was working.

Schelly writes that Stanley was in the latter part of his life "coping with the twin demons of alcoholism and clinical depression," a plausible statement (if one unsupported in the book by hard evidence) but at best a partial explanation for what was going on in the stories themselves. When Stanley was fully engaged, there was no comic-book writer who was better; as I wrote in Funnybooks, in a passage Schelly quotes, "There is in Stanley's best stories ... an intensity of feeling arising from a wholehearted engagement with the comic book medium and a corresponding delight in its capacity for expression." In many stories, later ones especially but also more than a few from his prime years, it's as if he resists surrendering to that delight, and the stories go slack. Perhaps depression and alcoholism pulled him down; or it may be—and this is the explanation I lean toward—they only reinforced a sort of impatience with himself that drove him to lie to his friends about the New Yorker.

Stanley, who died in 1993, certainly had reason late in his life to know that his work was highly valued by people who found no dissonance between their love for Little Lulu and their enjoyment of the New Yorker; but maybe the good news came too late, or maybe there wasn't enough of it. I remember that when my Smithsonian book was published in 1982, I felt sure that it would ignite a new interest in Stanley and appreciation of his best work. That didn't happen. There has been reprinting of his stories since then, but even Stanley's best stories, with their free-roaming children and vigorous spankings, seem perishable in today's cultural environment. Those of us who cherish his work must expect continuing neglect.

A Few Corrections and Questions:

John Stanley: Giving Life to Little Lulu is admirably thorough and accurate, but here are a few quibbles:

Page 20: Steamboat Willie was of course a sound cartoon, not a silent cartoon, as Schelly says on this page. Thanks to Thad Komorowski for the catch.

Page 28: Her name was Alice Nielsen (not Nielson) Cobb; and Schelly says incorrectly that Kay Kamen installed her as the editor of the Mickey Mouse Magazine. Her association with the magazine came at the very end of its life (if then) during the transition to Walt Disney's Comics & Stories, of which she was indeed the editor.

Pages 31-32: The early days of Stanley's comic-book career are so clouded that it's tempting to find certainty, or mere likelihood, where none exists, and these pages, on which Schelly speculates about the beginnings of Stanley's association with Western Printing & Lithographing and his editor, Oskar Lebeck, should be approached cautiously. When and where did Stanley's first comic-book work appear? In which issue of Our Gang Comics? Schelly and Frank Young say No.3, Hames Ware and I inclined toward No. 6 when we spread out the early issues and compared them closely.

Page 103: Schelly writes that Little Lulu's sales probably "gradually softened" in the late 1950s although the decline "hasn't been documented." There's really no way to "document" the sales decline except through the royalty reports sent to Lulu's creator, Marjorie Henderson Buell ("Marge"), by Western Printing & Lithographing, and those reports based her royalties on the number of copies printed. Those press runs declined gradually in the 1950s.

Pages 120-21: Schelly identifies the artist represented on these two pages as Gerald McCann, but Hames Ware, whose judgment I trust in such matters, says the artist is actually Paul Parker.

| Many cartoon characters were enlisted as mascots in World War II, even, unlikely as it might seem, Little Lulu. |

[Posted October 16, 2017; one correction added, October 17, 2017, and a second correction added, October 22, 2017]