COMMENTARY

The Newsprint Mouse and Duck

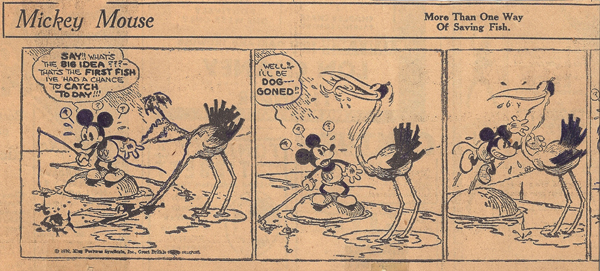

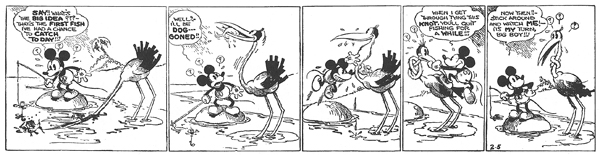

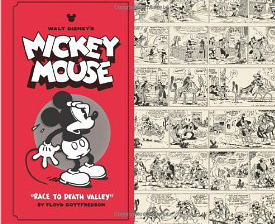

There are a great many things right about Race to Death Valley, the first volume in Fantagraphics' new series devoted to Floyd Gottfredson's Mickey Mouse newspaper strip of the 1930s and 1940s, and not many things wrong. The biggest thing wrong is illustrated above, and it's a problem that I'm sure was beyond the ability of Fantagraphics or any other publisher to remedy, especially in today's economy. At the top is a portion of one the first Mickey Mouse strips, from February 5, 1930, as it appeared in the Oakland Post-Inquirer (I have only a small collection of newspaper strips, but happily some of the earliest Mickeys are among them). Just below it is the same strip as it appears in the Fantagraphics volume. I've reproduced the two strips in proportions as close to those of the printed versions as I could manage.

You can see the problem: the Fantagraphics version, although reproduced beautifully, is simply too small. This is of course a common problem where contemporary reprints of comic strips are concerned. The earlier the strips, the more acute the problem, because newspapers once printed comic strips much larger than they do today. But to "solve" it by reproducing the Mickey strips at an appropriate size, and thus making the book a great deal larger, would have been no solution at all, because it surely would have entailed production costs, and thus a price for the book, that would have been insupportable. So we must be pleased with what we have.

What we have is the wonderful Gottfredson comic strip of the mid-1930s in embryo, accompanied by a historical curiosity, the first few weeks of the strip as written by Walt Disney himself and penciled for eighteen days by Ub Iwerks. Or was it twenty-four days? The book gives different answers: the table of contents says that Iwerks penciled the strip through February 8, 1930, the twenty-fourth day, whereas Thomas Andrae, in his essay on Iwerks, says that Iwerks penciled only the first eighteen strips. The strip above was thus either penciled by Iwerks and inked by Win Smith, or both penciled and inked by Smith, who worked from Walt's scripts for a few months after Iwerks left the Disney studio. Pressed to say, I'd go for Iwerks and Smith, but I don't feel confident of that attribution.

Walt was wise to surrender the writing of the Mickey Mouse strip to Gottfredson in May 1930. The strips Walt wrote are overloaded with dialogue—a reflection, maybe, of the lack of opportunities for verbal humor in the animated cartoons—and much of that dialogue is, to be charitable, hopelessly cornball (as well as being hard to read in reduced size). Gottfredson started writing the strip about six weeks after the serial that gives the book its title got under way, and his writing was a step up, but not a large one. The "Death Valley" serial is so clumsily written that in the climactic action Mickey isn't even the hero, that role falling to the disguised character who calls himself the Fox and wears a disguise whose purpose is never clear.

But there are many compensations. I particularly like the way these early strips finesse the nagging question of just what kinds of creatures Mickey and his friends are. Here it's clear that, for example, some pigs are really people—a pig can be a farmer, for instance—but there are also pigs that are, well, pigs. Likewise, there are cats that are people, like Pegleg Pete, and there are cats that are cats, and so on, so that Mickey can ride a horse and still pal around with Horace Horsecollar, who's a horse, but not really. And there is of course Pluto, who is a dog of a wholly different kind from the dog-nosed characters that populate Mickey's world (Goofy isn't present yet in these stories). That distinction is at least implied in the later Gottfredson strips, but I don't think it's as clearly visible as it is the strips of early '30s, where Mickey's environment is more rural. And then there's the invigorating sense, less in "Death Valley" than in the episodes that follow (the book's strips end in January 1932) that Gottfredson, then still in his twenties, is rapidly getting better at his job. I'm very much looking forward to future volumes in the series.

But there are many compensations. I particularly like the way these early strips finesse the nagging question of just what kinds of creatures Mickey and his friends are. Here it's clear that, for example, some pigs are really people—a pig can be a farmer, for instance—but there are also pigs that are, well, pigs. Likewise, there are cats that are people, like Pegleg Pete, and there are cats that are cats, and so on, so that Mickey can ride a horse and still pal around with Horace Horsecollar, who's a horse, but not really. And there is of course Pluto, who is a dog of a wholly different kind from the dog-nosed characters that populate Mickey's world (Goofy isn't present yet in these stories). That distinction is at least implied in the later Gottfredson strips, but I don't think it's as clearly visible as it is the strips of early '30s, where Mickey's environment is more rural. And then there's the invigorating sense, less in "Death Valley" than in the episodes that follow (the book's strips end in January 1932) that Gottfredson, then still in his twenties, is rapidly getting better at his job. I'm very much looking forward to future volumes in the series.

To get a sense of how good Gottfredson was to become, you need not wait for those future volumes. You can instead pick up Volume 1 of Walt Disney's Comics & Stories Archives, from Boom! Studios, which reproduces the first two issues, dated October and November 1940, of that comic book. One of Gottfredson's best serials, "Island in the Sky," from 1936-37, was reprinted in those two issues. Actually, bare-bones reprints of Disney comic strips make up almost all the contents of Walt Disney's 1 and 2, and so this is, on the face of it, a rather peculiar reprint project. Not that I'm complaining. David Gerstein, the editor of both the Gottfredson series and the WDC&S Archives, writes in a foreword about how difficult it was for him, as a collector, to locate a copy of No. 1, and I don't think it ever has been easy. Back in the 1960s, when my collecting urge had revived and I was filling in long runs of Dell "funny animal" comic books, eight issues from the first year of Walt Disney's eluded me. Thanks to my friend Don Draganski, I now have photocopies of all of those issues, but color photocopies only of the first issue. Just a quarter million copies of the first issue were printed, and the press runs didn't top a million until 1942, so it's not really surprising that the early issues should be scarce.

The color in the new facsimile edition is rather odd. I haven't made a page-by-page comparison of the first issue—and, as I say, I have only a black-and-white photocopy of the second issue—but the color for the Robber Kitten text feature in No. 1 is dark and murky, compared with what I see in my color photocopies. And speaking of such, the color for the second issue looks for all the world as if it might have originated in such photocopies. This is not a huge deal. Comic-book color in the early forties was invariably crude, and I know from my own unhappy experience with A Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics that reproducing bad comic-book color both accurately and pleasingly can be frustrating and difficult. If the Archives series continues, as I devoutly hope, the facsimile pages will probably improve, too.

Gerstein contributes several historical pieces to the WDC&S volume, including two on Gottfredson serials. The Fantagraphics book is filled out with dozens of pages of the same sort, by Gerstein, Thomas Andrae, Alberto Becattini, and others. One piece, by Warren Spector, "creative director" of the videogame called Epic Mickey (complete with a large color portrait of Spector), clearly owes its place in the  Fantagraphics book to contemporary Disney marketing priorities, but it's an exception.

Fantagraphics book to contemporary Disney marketing priorities, but it's an exception.

Otherwise, my one serious cavil is with Andrae's essay on Iwerks, which is titled "In the Beginning: Ub Iwerks and the Birth of Mickey Mouse." This is a five-page article, illustrated with a large photo of Iwerks. By contrast, there's only one page devoted specifically to Walt Disney. In recent years the Iwerks family (with the encouragement of people who should know better) has worked very hard to propagate the highly questionable notion that Ub, rather than Walt, deserves the lion's share of the credit for inventing Mickey Mouse and ultimately for the success of the Walt Disney Company. Andrae's essay is occasionally illuminating, particularly in his close examination of a sheet of what are supposedly Iwerks's original drawings of Mickey and Minnie Mouse, but overall it is too closely aligned with the Iwerks partisans' aim.

(To read more about that sheet of drawings and closely related matters, you may wish to go to my July 7, 2010, post, titled "The Mysterious Mouse, Cont'd," and work your way back through several earlier posts. Some of this material has been recycled in Andrae's essay, in potted form and without attribution.)

[An August 12, 2011, update: The preceding paragraph is in error. I'm sure now that Andrae and I proceeded on parallel tracks, and there was no unacknowledged borrowing. Thanks to Gunnar Andreassen and David Gerstein for helping me see where I made my mistake.]

To state the obvious: There was nothing exceptional about Mickey Mouse in the beginning, nothing to set that character apart from many other cartoon animals, in design or personality (such as it was), or in any other way. It was not Ub Iwerks's drawings but Walt Disney's ingenious use of sound that put the Mickey Mouse cartoons ahead in the beginning, and steady improvement in stories and animation that kept them there.

Although most of the essays are solidly researched and read well, I can't help feeling that Gerstein has crossed the boundary into overkill in both books. As obsessive as I am about details myself, I still have trouble understanding why we needed full-page pocket biographies of the cartoonists who had anything at all to do with the Mickey Mouse strip in the years covered by the Gottfredson book. In the WDC&S volume, Gerstein's limited knowledge of the admittedly murky history of that publication trips him up when he tries to tell us more than he knows (for one thing, Eleanor Packer was never the editor of Walt Disney's Comics). Most annoying to me are the unctuous disclaimers in each book distancing their compiler from the naughty racial and ethnic prejudices on display in some of the comic strips. Surely there's no pressing need to apologize for breaches of contemporary political etiquette in comic strips that are eighty years old.

More Disney comic-book reprints are promised, including a series devoted to one-shots (starting with the elusive Donald Duck No. 4, from 1940) and a new Fantagraphics series that will start not with Carl Barks's earliest work but with some of his best, including "Lost in the Andes" and other stories from 1949. Barks has already been reprinted in toto, of course, first in the black-and-white boxed sets produced by Bruce Hamilton and Russ Cochran's Another Rainbow in the 1980s, and then in color paperbacks bearing Hamilton's Gladstone imprint in the 1990s. But now, finally, the job has been done right. Done in subdued and handsome color, that is, and without the disfiguring changes that Disney required Another Rainbow to make in "Voodoo Hoodoo" and other Barks stories, back in the days when a groveling apology for centuries of racial injustice wasn't enough and only rewriting history would do. Unfortunately, though, the job has been done right not in Barks's own country, the United States, but in Denmark, by the Egmont company, a major Disney licensee, in what is called the Carl Barks Collection.

Like the Another Rainbow sets, the new Egmont boxed sets total thirty volumes, but there will also be six supplementary volumes, five of which have already been published: an index, "who's who in Duckburg," collections of Barks's cartoons for the Calgary Eye-Opener and his "Barney Bear and Benny Burro" stories for Our Gang Comics, and a book about his work on the Disney cartoons. The book still in process will be devoted to Barks's paintings.

Geoffrey Blum, one of the principal authors of the commentaries in the Another Rainbow and Gladstone sets, is the sole author of the commentaries in the new Egmont sets and four of the supplementary volumes, although he has naturally drawn extensively on the work that he (and Hamilton, Andrae, and Don Ault) did for the earlier books. I've helped Egmont modestly in the preparation of the new sets, and as a courtesy I've been allowed to read Blum's commentaries. They're spaced through each volume, usually accompanying a relevant story. Blum wrote his commentaries in English, and they have been translated into Danish and other languages for publication in northern Europe. It is most unlikely that Blum's magnum opus will ever be published in English, and what a pity that is.

The Carl Barks Collection as a whole benefits immensely from the sense that the stories, and Barks's life and career, are being examined carefully by a single highly intelligent and sympathetic author, one who knows the Barks stories intimately and has read just about everything ever written about Barks. The unfortunate academic slant in some of the original Carl Barks Library essays (and that bubbles up occasionally in the new Gottfredson book, as in Andrae's digression on the Depression-era signficance of the rat-faced lawyer character Sylvester Shyster) is mostly gone in the new books, displaced by a welcome attention to what's actually on the comics pages. Blum is, strictly speaking, just as guilty of overkill as Gerstein—he grinds exceedingly fine in some of his essays, which are too obviously pages he was required to fill. The saving grace is that everything, even the arguably superfluous, is coming to us through one governing sensibility, so that there are echoes in the flimsier pieces of the more substantial essays.

But it's not just what Blum has written that makes his essays worth reading. We've known for many years that Barks relied on the National Geographic as a prime source for the settings of many of his stories, but in the Carl Barks Collection the color photographs that stimulated Barks's imagination when he was designing Plain Awful, the setting for "Lost in the Andes," are gloriously present as part of a Blum commentary, just pages away from Barks's depiction of Plain Awful itself. There are comparable spreads of Geographic photos for other stories, and illustrations from other sources as well.

What Blum has written is, to be sure, not the last word on Barks—his commentaries are occasionally (and unavoidably, given the nature of the project) repetitive, a few errors have crept in, and he sometimes feels obliged to put the best possible face on stories that defy admiration. And then, as a decisively complicating factor, there's Barks himself. I've been writing about him again myself in recent months, in my own book about comic books, and the man keeps surprising me as I learn more about him. His stories keep surprising me, too, because the best ones are so much better than they have any reason to be. It's illuminating to read other Dell "funny animal" comic books after reading Barks, as I've been doing lately, and to see how crude and unformed so many of them are, compared with the work of the master. Even Gottfredson's best serials, which are very good indeed, have nothing like the depth and subtlety of Barks's best stories. Barks's stories are completely the product of his mind and hand; Gottfredson shared the work with other writers and cartoonists. It made a difference.

There's no way that so miraculous a creator as Barks, producing incredibly rich stories in a despised medium, can be completely captured even inside the covers of a set of thirty beautiful books. And how lucky we are that such is the case.

[Posted August 8, 2011]