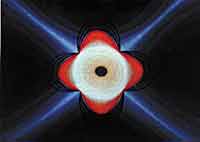

From Motion Painting No. 1. Copyright Fischinger Archive. |

CAPSULES

Motion Painting No. 1

Oskar Fischinger, 1947.

Oskar Fischinger (1900-1967) was a German maker of abstract films whose name almost invariably turns up in animation histories, including mine, only in connection with his brief, unhappy association with Walt Disney during work on the Bach section of Fantasia, in 1938-39. He was an intensely serious, uncompromising filmmaker who constantly ran afoul not just of predictable enemies, like the Nazis, but of people who should have been his allies. Much of his work can be intimidating in its rigor; but that is not true at all of his greatest film, Motion Painting No. 1, which he completed in 1947.

I

saw the restored version of this Fischinger film twice in one afternoon

at the Museum of Modern Art, in June 1997, and again in October

2000 at the National Gallery of Art. The latter showing was part

of a program hosted by William Moritz, who with Fischinger's late

widow, Elfriede, has done more than anyone else to keep Fischinger's

work before the public. My admiration for Motion Painting No.

1 has increased each time I've seen it. A stop-motion film,

painted in oil on plexiglas, it's easily the best of the several

dozen Fischinger films I've seen. It's a great pity he wasn't able

to make more such "motion paintings."

I

saw the restored version of this Fischinger film twice in one afternoon

at the Museum of Modern Art, in June 1997, and again in October

2000 at the National Gallery of Art. The latter showing was part

of a program hosted by William Moritz, who with Fischinger's late

widow, Elfriede, has done more than anyone else to keep Fischinger's

work before the public. My admiration for Motion Painting No.

1 has increased each time I've seen it. A stop-motion film,

painted in oil on plexiglas, it's easily the best of the several

dozen Fischinger films I've seen. It's a great pity he wasn't able

to make more such "motion paintings."

According to Moritz's comprehensive account of Fischinger's career ("The Films of Oskar Fischinger," Film Culture 58-59-60, 1974), Motion Painting No. 1 originated in 1934, when Fischinger first envisioned "making a grand and glorious film to be accompanied by Bach music." He returned to this project a decade later, with the support of a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation, but after two years of false starts—"striking concepts [that] would have required a great deal of expensive help in production and probably expensive equipment," according to Moritz—"the grant film was still not really begun."

Baroness Hilla Rebay, then the curator of the Foundation, "became increasingly insistent since she had nothing to show for the foundation's investment after two years," Moritz writes. "Finally, in desperation, ... Fischinger dispensed with close synchronization to Bach, and resolved on using the one technique which he could relatively easily produce entirely by himself—he began painting as he usually did with a board fixed tight to a specially constructed easel with even lighting on each side to prevent reflection, and after each small brush stroke he rocked backward in a swivel chair and pulled a shoe string attached to the single-frame lever on a camera set up behind him focused exactly on the painting. ... Fischinger worked for several months on the first board, and when the paint grew too thick, he six times placed a plexiglas sheet over and continued, so that the finished film, eleven minutes long, constitutes one single [']take,' one single flow of action."

Moritz writes that "Fischinger painted every day for over five months without being able to see how it was coming out on film, since he wanted to keep all the conditions, including film stock, absolutely consistent in order to avoid unexpected variations in quality of image."

It was only in this film that Fischinger found a wholly satisfactory answer to the challenges that have defeated so many makers of abstract animated films. It is all too easy for the animation in such films to lose its abstract quality, slipping into the suggestion of natural phenomena or even purposeful movement. As I watched earlier Fischinger films on Moritz's program, I struggled against the temptation to interpret the animation as a school of fish, or falling leaves, or something else of the kind. It's easy to imagine, in watching such films, how Walt Disney yielded to such temptation when Fischinger was working for him on Fantasia and then pressed Fischinger to go further in that direction.

The abstract filmmaker who subdues his animation too thoroughly runs another risk, though, of reducing it to the numbingly mechanical. In Fischinger's case, the dangers in that direction were aggravated by his tendency to resort repeatedly to the same shapes—concentric circles, lozenges, and so on—and by his very seriousness. Wit is not a distinguishing characteristic of Fischinger's work, even in his famous Muratti marching-cigarettes commercial film from 1934.

Similar traps lie in wait for easel painters (of which Fischinger was also one, although he always considered himself a filmmaker first). What was critical to the triumph of abstract expressionism in postwar America was that painters completely avoided them—and even, in the case of Jackson Pollock, the greatest of the abstract expressionists, introduced a strong suggestion of movement, still without inviting comparisons with the external world. I know of only a few abstract animated films, notably the best work of Norman McLaren, that are comparably successful.

There is purposeful movement in Motion Painting No. 1, but the purposeful movement is clearly the artist's own. As the camera records, frame by frame, the activity of his brush, Fischinger himself is a constant presence in this film, as he is in no other that I've seen. Fischinger has been likened to Vasily Kandinsky, but Piet Mondrian, his Dutch contemporary, is a more apt comparison. Mondrian's paintings, as rigorously abstract as Fischinger's films, can seem in reproduction a bit dry and cool, but the actual canvases have—thanks to their impasto, the accumulated evidence of how carefully Mondrian worked out the exact positions of his lines and blocks of color—an intensely human quality. It's such evidence of the artist's unseen hand that makes Motion Painting No. 1 so moving, too. It is at once the most abstract and the most personal of films, and that is why it is so powerful.

As Moritz says, the film "shows a variety of styles from the soft, muted opening to the bold conclusion through a series of spontaneous changes prepared without any previous planning. All of the figures are drawn free-hand without aid of compasses or rulers or under-sketching, even the incredibly precise triangles of the middle section." The film actually seems to start rather slowly, with an overdose of Fischinger's trademark concentric circles (not really spirals, although he also uses those in other films), but then picks up speed. As Motion Painting No. 1 moves forward, it becomes much more inventive, and then astonishingly rich in its shapes and colors.

Motion Painting No. 1 would no doubt be splendid even as a silent film, but it benefits greatly from its soundtrack, Bach's third Brandenburg Concerto. Because the music is abstract, it encourages viewing the film as its visual equivalent—not as a visualization of the music, but as a creation of the same kind, even as a creation on the same level of inspiration. Motion Painting No. 1 is, as Moritz writes, a "formidable tour de force, astonishingly successful, and a fitting display of achievement for the last film of an acknowledged master."

The "last film," apart from a few TV commercials and fragments of unrealized projects, even though Fischinger lived for another twenty years, until January 31, 1967. As Moritz explains, the reasons were complex, but certainly Hilla Rebay's hostility to the finished film was an important factor. As baffling as it may seem, Rebay was outraged by "Fischinger's awful little spaghettis," and he received no more financial support from the Guggenheim Foundation. He could afford to have only a half dozen 16mm prints of Motion Painting No. 1 made, and they brought him little monetary return.

[Motion Painting No. 1, in its glorious restored version, is available on videotape from the Fischinger Archive in Long Beach; contact the Archive through its Web site. Signed copies of Bill Moritz's newly published biography of Fischinger are available from the Center for Visual Music.]

[Posted May 2003; updated January 24, 2004]